In 1992, unemployment in France was high and rising. Inflation was almost nothing. The French government seemed

Question:

In 1992, unemployment in France was high and rising. Inflation was almost nothing. The French government seemed to respond by tightening up on money and raising interest rates.

Madness? Not really, but an example of the policy dilemma that can arise with fixed exchange rates. France was a member of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) of the European Monetary System. Membership committed the French government to keep the exchange rates between the French franc and the currencies of the other member countries within small bands around the central rates chosen for the fix.

To understand France we actually need to start with Germany, the largest member of the ERM. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989, and German unification proceeded rapidly over the next year, politically, financially, and economically.

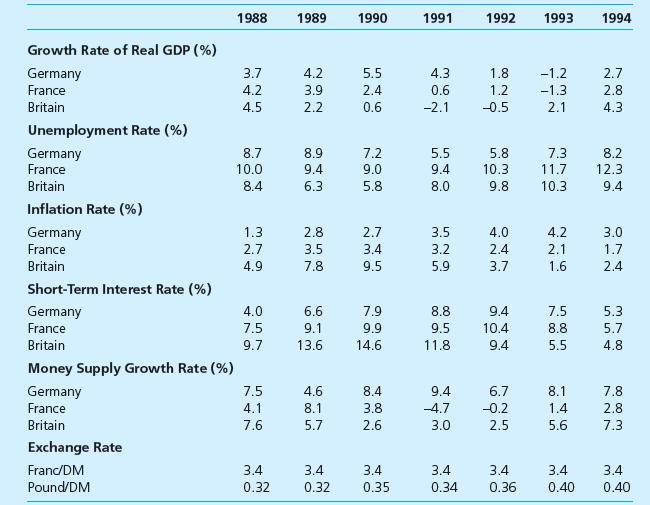

German government policy toward unification included support for the eastern part in the form of transfers, subsidies, and other government expenditures on such things as public infrastructure investments. This expansionary fiscal policy increased aggregate demand. Domestic production expanded rapidly in 1990 and 1991, and unemployment fell, but the economy began to overheat as demand exceeded production capabilities, so that the inflation rate increased.

German policymakers, especially those at the Bundesbank (Germany’s central bank), loathe inflation. History matters—the hyperinflation of the 1920s in Germany is considered to be the economic disaster of the past century for Germany.

In response to the rise in inflation, the German monetary authorities tightened up on monetary policy, after a spurt in money growth in 1990–1991 resulting from monetary unification.

Interest rates rose. This monetary tightening slowed the economy during 1992–1993.

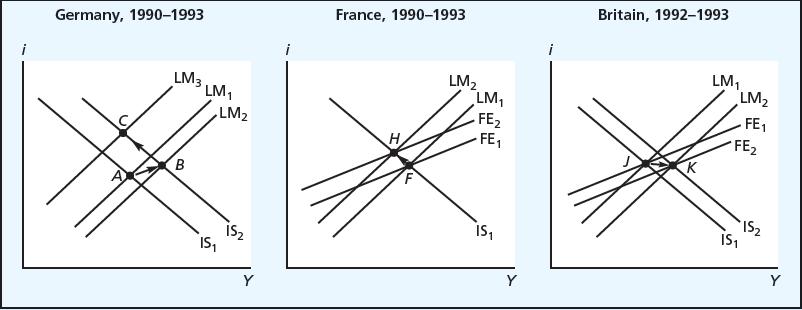

We can capture the main elements of the German story in an IS–LM picture. Germany began at point A. The fiscal expansion shifted IS 1 to IS 2 , and the increased growth rate of the money supply shifted LM 1 to LM 2 . At the new equilibrium point B, real domestic product was higher, but the economy was trying to push past its supply capabilities. In response to the internal imbalance of rising inflation, the Bundesbank reduced money growth, shifting LM 2 to LM 3 .

Interest rates rose and domestic product declined as the economy moved toward point C .

In this way the German government adopted policies that focused almost completely on internal political and economic problems. (In fact, although we could add the FE curve to Germany’s picture, we have instead omitted it to emphasize this internal focus of German policy.) Meanwhile, back in France . . .

In 1990, the French economy was already weak and weakening. The unemployment rate was 9 percent and rising. For internal reasons the French government probably wanted to shift to an expansionary policy. But it had an external problem.

Rising interest rates in Germany could set off a capital outflow that would threaten the fixed exchange rate between the franc and the DM.

France had to respond to this incipient external imbalance by tightening up on money and raising French interest rates. Unfortunately, for political reasons, fiscal policy could not turn expansionary.

The assignment rule could not be used. Instead, the higher interest rates made the French economy worse. The growth rate of real French GDP declined from 1989 through 1993, and real GDP actually fell in 1993. The French unemployment rate rose from 1990 through 1994.

In France’s picture, France began at point F , with aggregate demand already weak and unemployment high. The rise in Germany’s interest rate shifted France’s FE curve up or to the left (FE 1 to FE 2 ).

To avoid capital outflows and a payments deficit, the French monetary authorities responded by tightening money, shifting LM 1 to LM 2 . As the economy moved toward point H, demand and production weakened and the unemployment rate rose.

However, this was not always enough.

International investors and speculators doubted the resolve of the French (and most other non-German members of the ERM) to stick to fixed exchange rates. Major speculative attacks occurred in September 1992, November 1992, and July 1993. In these the FE curve for France shifted sharply up or to the left. The French government responded with massive official intervention, buying francs and selling DM, and with high short-term interest rates to discourage the speculative outflows. Total intervention by all ERM members in September 1992 was over

$100 billion, with capital losses of about $5 billion to the central banks that bought currencies of the countries (Britain, Italy, Spain, and Portugal)

that then devalued or depreciated anyway. Total intervention in July 1993 was also more than $100 billion, with the French central bank alone selling more than $50 billion of DM in defense of the franc. Official reserve holdings of the French central bank declined close to zero, but the French government was “successful.” The franc was not devalued.

The third largest economy in the European Union is Britain. Britain’s journey through these years was different. Britain was not a member of the ERM until joining in 1990, when it committed to a pound–DM rate of about 0.35. The next two years were not good for Britain. To defend the fixed rate, the growth rate of the British money supply had to be kept low (although at the same time British interest rates could decline, starting from a high level). A severe recession with two years of decline in real GDP hit, and the unemployment rate rose to about 10 percent. While Britain’s and France’s stories are broadly similar during these years, Britain’s recession was worse.

In 1992, Britain’s story diverged. As a result of the speculative attack on non-DM currencies in September 1992, Britain left the ERM. The British government spent close to half of its official reserves defending the pound before surrendering.

Britain shifted to a floating exchange rate, and the pound depreciated by over 10 percent against the DM. This improved British price competitiveness.

In addition, the British government could allow its money supply to grow more quickly. Interest rates fell sharply in 1993 and real GDP began to grow.

Britain’s unemployment rate plateaued in 1993 and declined in 1994 (while the unemployment rate was still rising in both France and Germany). After declining in 1993, the inflation rate increased a little in Britain in 1994, but not even close to enough to reverse the gain in price competitiveness from the currency depreciation. Britain’s depreciation of 1992 seems to have been successful.

Let’s pick up Britain’s picture as Britain left the ERM in 1992. (Its picture for 1990–1992 is similar to that of France.) The initial situation, just before the departure, is at point J . With the depreciation of the pound, the improvement in price competitiveness shifts FE 1 right to FE 2 and moves IS 1 right to IS 2 . The money expansion shifts LM 1 right as well to LM 2 . The British economy shifts toward point K , with higher real domestic production and a lower interest rate.

Tales have lessons. The lesson of this tale is that countries can be forced to choose between fixed exchange rates and control over their internal balance. When large countries choose internal balance, the choice gets tougher for smaller countries.

Germany ran its policies mainly to satisfy internal objectives (like the United States in the 1960s).

This created problems for other ERM members—

conflicts for them between internal and external balance. Both France and Britain faced a dilemma:

high unemployment and a tendency toward payments deficits. For a while, both responded with tight money that tried to achieve external balance but made the internal imbalance (high unemployment) worse.

All of this did not completely convince international investors and speculators. With the speculative attack of September 1992, the paths diverged. France defended the fixed rate, at further cost to internal balance.

Britain surrendered, withdrawing from the ERM.

This allowed Britain to address its internal imbalance.

Expansionary policy and the competitiveness gained from the pound’s depreciation rekindled economic growth. The unemployment rate declined.

The speculative attack in July 1993 led to a semi-surrender even by France and other ERM members. They widened the allowable bands around the central rates from plus or minus 2.25 percent to plus or minus 15 percent. This widening of the band forestalled any further speculative attacks. But, during the next years, the franc–DM rate seldom was more than 3 percent from its central value. France continued to direct its policies to keeping the franc exchange rate steady against the DM, and France’s unemployment rate remained high.

DISCUSSION QUESTION Explain whether or not the story could have turned out better if

(a) Germany would have raised taxes in 1990 or

(b) France would have reduced taxes in 1991.

Step by Step Answer: