A pain is spreading down my arm. Twenty of us, seated in ten rows, two to a

Question:

A pain is spreading down my arm. Twenty of us, seated in ten rows, two to a bench, are paddling furiously aboard a 40 ft dragon boat. It is a disconcerting, not to mention exhausting, experience. As we plough down the Thames in London’s Royal Albert Dock, we take orders from a helmsman and keep time to a drum. It’s almost as if we’re slaves in a galley, except we’re supposed to be doing this for fun. I’m racing with the Thames Dragon Boat Club, and I’m quickly learning that perfectly synchronised paddling is the key to survival. Without it there’s no way to generate speed through the water.

‘Watch the strokes at the front of the boat and keep in time with them,’ shouts team coach Liam Keane, seated beside me in the boat. ‘Ideally, we want everyone’s paddles entering and exiting the water at exactly the same time. You could have twenty enormous beefcakes powering a dragon boat, but if they’re not paddling in time with each other, they won’t be effective.’

‘When people first start this sport, they just go for power,’ Keane adds. ‘But you need to get into a team mentality. Get your timing locked in and feel the rhythm of the boat.’ His voice starts to waver as the helmsman suddenly barks out the orders to increase the pace, at which the 10-year-old drummer, Amy, seated at the prow, ups the tempo accordingly. We’ve reached 65 strokes a minute, which is close to race pace. My arms and shoulders are beginning to protest as the lactic acid builds up, and my heart pumps wildly. Although each paddling action is identical, one has to concentrate hard to get the timing and the angle of entry into and out of the water just right.

On more than a few occasions I catch a crab and splash the right ear of the female paddler in front of me with ice-cold water. In due course I get my own dousing courtesy of the chap sitting behind me, who is also a beginner. There’s neither the time nor the spare breath to apologise. I’m told later that we achieved a top speed of about 8 knots. With a full crew of experienced paddlers in a race situation, this might reach 9 knots. The tight teamwork required and the simple technique make dragon boating the perfect corporate team sport. ‘Anybody can do this,’ Keane stresses. ‘You can put a bunch of novices into a boat and within ten minutes they’re paddling. You couldn’t do that with rowing because it’s more of a fine art. They might end up capsizing the boat.’

Paul Coster, the club chairman, insists that dragon boating is the truest of all team sports. ‘The camaraderie is so important’ he says. ‘We train together, we race together, we get drunk together. That’s why lots of companies do this. It’s great for team-building.’

Back on the water, our practice is beginning to pay off. Suddenly we all lock into the same rhythm – 20 paddlers in perfect unison. It almost feels as if we’ve ceased to be separate athletes and have joined forces into a single entity, like a shoal of fish or a flock of birds. And for a blissful moment, I forget the pain.

Discussion questions

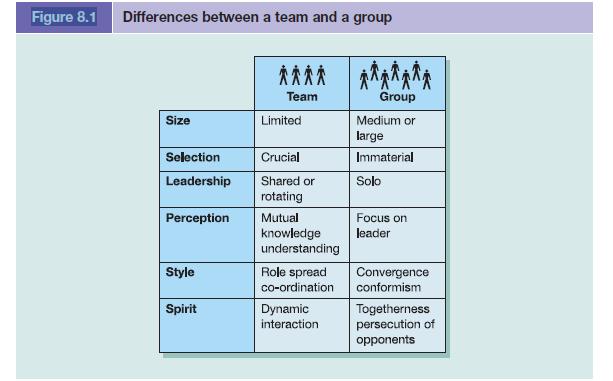

1. Using the model in Figure 8.1 to structure your answer, explain why dragon boat racing can be a useful means of turning groups into teams.

2. What can we learn from the article about the importance of the ‘informal’ aspects of organisations? What problems could the informal group or organisation cause for managers in an organisation with a highly diverse workforce?

Step by Step Answer:

Management And Organisational Behaviour

ISBN: 9780273728610

9th Edition

Authors: Laurie J. Mullins, Gill Christy