Starting in the 1990s, the U.S. electric utility sector underwent a process of consolidation. Utility companies merged,

Question:

Starting in the 1990s, the U.S. electric utility sector underwent a process of consolidation. Utility companies merged, acquired other utilities, and moved from their home bases in one state across state lines. Through such activities, Duke Energy, Southern Company, and NextEra Energy became the largest U.S. investor-owned utilities. These three companies had different specializations. Duke and Southern were the largest coal and natural gas generators in the United States, while NextEra was the largest wind and solar owner and operator, not just in the United States but in the world.

The Shift to Renewable Energy

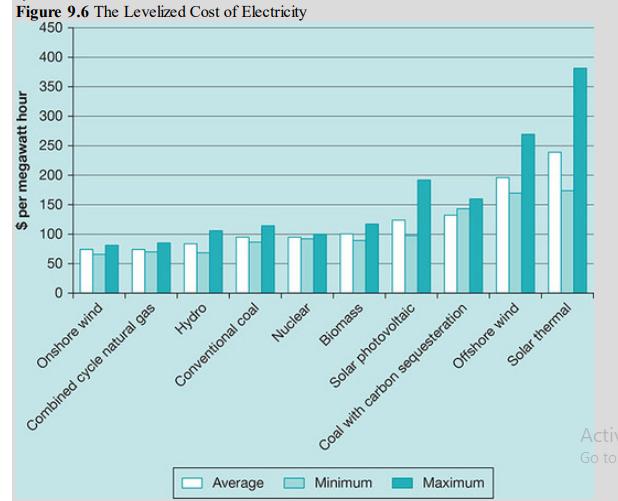

The types of fuels the world uses to meet electricity demand has been shifting gradually from fossil fuels to renewable energy. 25 In 1973, about 75% of the world’s generation of electricity came from coal, oil, and natural gas, but in 2016, this number had fallen to 66%. Renewables went from 0.6% of electricity generated in 1973 to 7.1% in 2015 (Figure 9.6). The use of coal in the United States dropped for a number of reasons. Extensive pollution control standards put in place because of coal’s negative health effects curtailed coal’s growth. Another concern that led to less growth in the use of coal was the greenhouse gases that coal-fired power plants emit. In general, generating electricity from coal became more expensive than generating it from wind or natural gas. Joined with combined-cycle natural gas, wind had become the first choice of most electric utilities when this option was available, and they needed to add generation capacity to their systems.

Cost is on the vertical axis, ranging from 0 to 450 with an increment of 50. Electricity generating methods are on the horizontal axis with bars for Average, Minimum, and Maximum Cost for each method. For electricity produced by Onshore wind and Combined cycle natural gas, all three costs are under 50 dollars. For hydro and conventional coal, while the average and minimum cost remain below 100 dollars, the maximum cost is above 100 dollars. For Nuclear, minimum and average are just below 100 dollars and maximum are at 100 dollars. For Biomass, average is at 100 dollars, minimum is below 100 dollars, and maximum is over 100 dollars. For Solar photovoltaic, Average remains at 100 dollars, but minimum is above 100 dollars and maximum are almost 200 dollars. For coal with carbon sequesteration. Average and minimum are under 150 dollars and maximum is over 150 dollars. For Offshore wind, average is 200 dollars, minimum is above 150 dollars, and maximum is above 250 dollars. For solar thermal, the average is above 200 dollars, minimum is below 200 dollars, and maximum is below 400 dollars.

The Threat of Climate Change

One reason renewable energy made inroads in the United States and elsewhere was concern about climate change, described above in the Exxon Mobil case and in Chapter 7.

Concerns about climate change and other issues such as energy security led to U.S. government efforts to promote renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power. The U.S. Congress provided a wind production tax credit of 2.3 cents per kilowatt of electricity generated for any facility built before 2020, with the amount of the credit declining each year from 2017 to 2019. Congress also extended a solar investment tax credit of 30% of cost for residences and commercial establishments. How long the credit would remain in force was uncertain. Many U.S. states mandated that utilities generate more of their power from renewables. Iowa introduced the first of such mandates in 1991. By 2018, 29 states with 56% of U.S. electricity sales had such mandates in place. Government encouragement of wind and other renewables had a long history starting in the 1970s.

NextEra’s Evolution as a Renewable Power Generation Leader

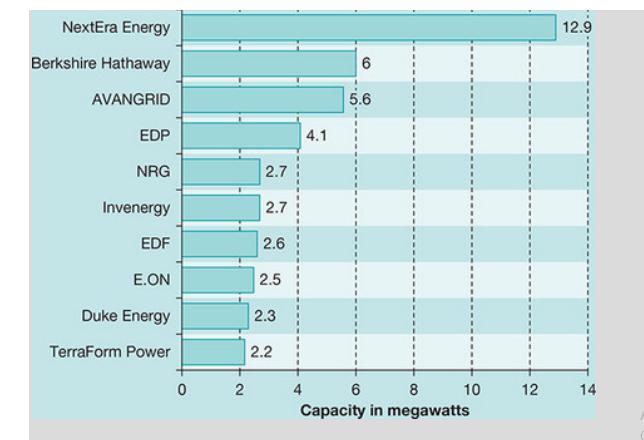

The U.S. electric utility industry was responsible for roughly 30% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. NextEra had been an industry leader in addressing the issue (Figure 9.7). While the company generated about 46% of its electricity from natural gas and another 26% from nuclear power, nearly 25% came from wind and solar energy. This concentration on renewable energy made it the largest producer of electricity from wind and solar energy in the world. Its ability to capture the renewable market permitted NextEra to grow despite relatively flat demand for power in the United States.

Figure 9.7 Leading U.S. Wind Energy Operators in 2016 Based on Ownership

The graph plots organizations on the vertical axis and capacity in megawatts on the horizontal axis, ranging from 0 to 14 with an increment of 2. NextEra Energy is the highest at 12.9 megawatts, followed by Berkshire Hathaway at 6, and AVANGRID at 5.6. Next are EDP at 4.1, NRG at 2.7, and Invenergy at 2.7. The next three are EDF at 2.6, E.ON at 2.5, and Duke Energy at 2.3. The lowest is Terra Form Power at 2.2.

NextEra’s predecessor company had started building its renewables business in the 1990s, primarily for commercial reasons. Over time, the company steadily added to its renewable's portfolio. In 2006, NextEra acquired Wind Logics of Minnesota. This company was largely considered the best among U.S. companies in forecasting wind patterns. NextEra found and leased some of the best wind sites in the United States. It outbid competitors on the building of wind and solar farms. By 2016, NextEra Energy and its subsidiaries owned 85 wind farms in 17 U.S. states and three Canadian provinces. It was also the co-owner and operator of Solar Energy Generating Systems, the world’s largest solar power generating facility.

NextEra had grown its renewable power investments in a prudent way. For instance, it kept its debt low by funding projects with cash and credit lines that did not involve financing charges. It also built its renewable installations only after its customers (electric utilities) provided it with long term power purchasing agreements. In this way, it avoided the debt problems that other U.S. wind energy installers such as NRG and SunEdison had experienced. As a large purchaser of turbines, the company obtained good deals from the turbine manufacturers, not only GE but Vestas and Siemens.

NextEra relied heavily on federal tax credits for solar and wind power. From 2015 to 2018, NextEra made use of $401 million in federal tax credits to build wind power units. It was the country’s largest beneficiary of such credits. The company CEO James Robo recognized that his company would face a substantial problem if federal wind tax credits expired in 2020.

NextEra planned to continue its move to renewables, which accounted for one third of its revenue and had been very profitable, generating $2.9 billion in net income for the company in 2018. By that year, the company had 28,000 megawatts of wind and solar projects and was aiming to expand that amount to 40,000 megawatts in two years. NextEra was in the midst of going beyond its utility customers and building wind and solar farms for companies like Google, whose cloud servers consumed huge amounts of energy and who were heavily committed to transitioning to renewable power.

Part of NextEra’s plan going forward was to accumulate and control centralized renewable power facilities. It did not want to have to compete with customers who used rooftop solar panels to generate their own power. If a household or commercial establishment generated excess electricity, NextEra would have to absorb that electricity onto its transmission system and pay the customer for it. This path forward was not one NextEra wanted to take. While in general, environmentalists approved of the company’s renewable energy efforts, they had been critical of what they considered to be attempts by NextEra to slow the deployment of rooftop solar.

What Should NextEra Do Next?

Many executives at NextEra wanted to maintain the company’s commitment to renewable power, but they also had an obligation to serve the company’s shareholders. They could maintain the commitment to renewables only if doing so was financially prudent. NRG’s CEO David Crane had been ousted by his company’s board of directors for preserving the company’s commitment to renewable energy even as the company was losing significant amounts of money in carrying out wind and solar projects. NextEra CEO Robo recognized that federal tax credits had been critical to the growth of NextEra’s renewables business and that his company would face a substantial problem if these credits expired in 2020. The company had to decide on whether the company should maintain its commitment to wind and solar.

Use the weight-of-reasons framework to identify and evaluate NextEra’s strategic options. Is it possible for NextEra to address the grand challenge of climate change and earn a profit? What options does the company have in the short term and long term? How do future innovations in solar, wind, and other renewable energy options fit in? Should NextEra get involved in the political process, and in what way? Who are the stakeholders to the company’s decision, and how are they likely to be affected by each option?

Step by Step Answer:

Managing Business Ethics Making Ethical Decisions

ISBN: 9781506388595

1st Edition

Authors: Alfred A. Marcus, Timothy J. Hargrave