For Linda Skoglund, getting a pedicure on a busy Tuesday afternoon was a career turning point. It

Question:

For Linda Skoglund, getting a pedicure on a busy Tuesday afternoon was a career turning point. It ran against her Midwestern work ethic. And certainly, there was plenty of work piled up at J.A. Counter &

Associates, the $2.5 million insurance and investment advisory firm she owns in New Richmond, Wisconsin.

On the other hand, canceling her visit to the salon that day could have sent a bad message. It risked signaling to her 15 employees that they weren’t allowed to do whatever they wanted at any given time during work hours.

And that would tank her plans to overhaul the work environment at J.A. Counter.

In recent years, profits had been sluggish, and the company was lagging 15 percent behind industry benchmarks for revenue per employee. Skoglund had started doing more comprehensive performance reviews, increased the company’s sales goals, cut expenses, and fired a couple of employees. Those adjustments boosted the bottom line slightly, but at a cost. “There were so many changes, it affected morale,” Skoglund says. “A lot of people feared for their jobs.” Not only that, she was constantly being forced to put out minor fires, which prevented her from focusing on sales. “I was tired of problems always ending up with management,” she says.

“I wanted to move away from KinderCare.”

Finally, last spring, Skoglund decided to implement a new way of managing—a system known as a resultsonly work environment, or ROWE. Now, J.A. Counter’s employees can leave the office whenever they please.

They don’t have to tell anyone where they are going or why. If an employee chooses to share the fact that he or she is taking the afternoon off to go to a baseball game, no one’s allowed to make muttering comments about his or her work ethic. It’s no surprise that this system has boosted morale; perhaps more significant, Skoglund says it has improved productivity as well.

Of course, companies have been touting flexible work arrangements for years. At most businesses, however, freedom has a limit: It’s allowed only a couple of days a week or only for certain employees. But Cali Ressler and Jody Thompson, the two women who developed ROWE, say the system doesn’t work unless it works for everyone—even the assistants, secretaries, and receptionists who have traditionally been at the mercy of a boss. Ressler and Thompson came up with the idea for ROWE while they were working in the HR department at electronics giant Best Buy, which wound up offering it to 3,000 employees at its corporate headquarters. . . .[In 2008], Ressler and Thompson left Best Buy and ventured out on their own as consultants and authors of the recently published book Why Work Sucks and How to Fix It. So far, they have worked with a few small companies, including J.A. Counter, and the results have been surprising.

Changing the entire philosophy of work at corporate behemoth Best Buy was hard enough; at smaller companies, the two have found, it can be even harder.

That’s because at small companies, employees are more likely to wear many hats—at J.A. Counter, for example, one person is in charge of HR, accounting, and IT. Employees who play so many roles are more hesitant about leaving the office, and their bosses are more reluctant to let them go. Plus, smaller companies often don’t have well-defined job descriptions, so it’s difficult to judge whether employees are doing their jobs if they are not spending every day in the office. And when an employee in Best Buy’s IT department takes the afternoon off, another one can cover for him or her. Not so at a company filled with one-person departments.

Many of Skoglund’s employees were skeptical when she announced the move to ROWE. “I’ll believe it when I see it,” said financial adviser Matt Radintz. Then the kicker: “What about Judy?”

Judy Wentlandt is J.A. Counter’s receptionist. The team could readily imagine the salespeople—many of whom already had flexible schedules—moving to ROWE. But a receptionist? Skoglund was adamant—

yes, the receptionist. She wasn’t sure just how it would work; she told her staff members to figure it out. Two weeks later, they came back with a simple plan. When Wentlandt gave advance notice that she would be at home or off-site, volunteers would be asked to fill the receptionist’s role.

New technology allows all employees to view their desktop from any station in the office. The company is considering installing a new phone system that will allow Wentlandt to answer phones from off-site locations, giving her even more flexibility. “I don’t have the spontaneity that everyone else has,” Wentlandt says.

“But if I need coverage, I get it.” She has left work to take her grandson to a museum and to attend her father’s birthday party. Before, she would have had to take vacation time or skip those events. . .. But the shift to ROWE has forced J.A. Counter’s managers to focus more on outcomes than on hours.

Before moving to the new system, each manager met with his or her direct reports and wrote out detailed job descriptions, with expectations and measurements.

Now, Mehls says, J.A. Counter’s employees are like “mini entrepreneurs,” managing their own schedules and focusing on delivering results instead of just pulling in a paycheck.

Questions for Discussion

1. What influence tactics and power bases are evident in this case? Explain.

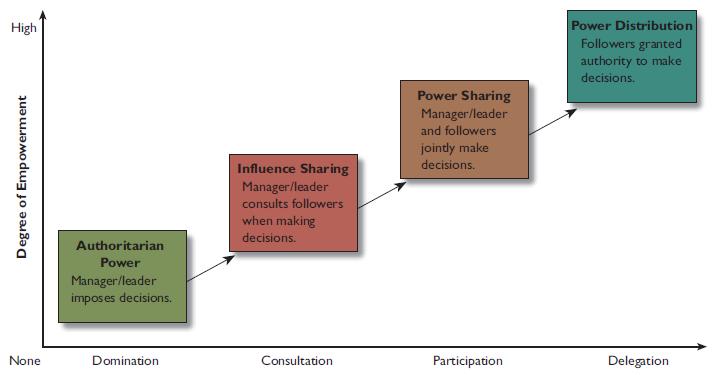

2. Where would you plot J.A. Counter’s ROWE program on the empowerment grid in Figure 15–2? Explain.

Figure 15-2

3. Has employee empowerment been taken too far in this case? Explain.

4. What impact do you expect the ROWE program to have on organizational politics at J.A. Counter? Explain.

5. What are your own feelings about the ROWE concept?

Would you like to work in such an unstructured situation? Explain why or why not.

Step by Step Answer: