Discipline, honesty, and a strong work ethic were three key traits that John and Mary Andersen instilled

Question:

Discipline, honesty, and a strong work ethic were three key traits that John and Mary Andersen instilled in their son. The Andersens also constantly impressed upon him the importance of obtaining an education. Unfortunately, Arthur's parents did not survive to help him achieve that goal. Orphaned by the time he was a young teenager, Andersen was forced to take a full-time job as a mail clerk and attend night classes to work his way through high school. After graduating from high school, Andersen attended the University of Illinois while working as an accountant for Allis-Chalmers, a Chicagobased company that manufactured tractors and other farming equipment. In 1908, Andersen accepted a position with the Chicago office of Price Waterhouse. At the time, Price Waterhouse, which was organized in Great Britain during the early nineteenth century, easily qualified as the United States' most prominent public accounting firm.At age 23, Andersen became the youngest CPA in the state of Illinois. A few years later, Andersen and a friend, Clarence Delany, established a partnership to provide accounting, auditing, and related services. The two young accountants named their firm Andersen, Delany & Company. When Delany decided to go his own way, Andersen renamed the firm Arthur Andersen & Company.In 1915, Arthur Andersen faced a dilemma that would help shape the remainder of his professional life. One of his audit clients was a freight company that owned and operated several steam freighters that delivered various commodities to ports located on Lake Michigan. Following the close of the company's fiscal year but before Andersen had issued his audit report on its financial statements, one of the client's ships sank in Lake Michigan. At the time, there were few formal rules for companies to follow in preparing their annual financial statements and certainly no rule that required the company to report a material "subsequent event" occurring after the close of its fiscal year-such as the loss of a major asset. Nevertheless, Andersen insisted that his client disclose the loss of the ship. Andersen reasoned that third parties who would use the company's financial statements, among them the company's banker, would want to be informed of the loss. Although unhappy with Andersen's position, the client eventually acquiesced and reported the loss in the footnotes to its financial statements.Two decades after the steamship dilemma, Arthur Andersen faced a similar situation with an audit client that was much larger, much more prominent, and much more profitable for his firm. Arthur Andersen & Co. served as the independent auditor for the giant chemical company DuPont. As the company's audit neared completion one year, members of the audit engagement team and executives of DuPont quarreled over how to define the company's operating income. DuPont's management insisted on a liberal definition of operating income that included income earned on certain investments.Arthur Andersen was brought in to arbitrate the dispute. When he sided with his subordinates, DuPont's management team dismissed the firm and hired another auditor. Throughout his professional career, Arthur E. Andersen relied on a simple, fourword motto to serve as a guiding principle in making important personal and professional decisions: "Think straight, talk straight." Andersen insisted that his partners and other personnel in his firm invoke that simple rule when dealing with clients, potential clients, bankers, regulatory authorities, and any other parties they interacted with while representing Arthur Andersen & Co. He also insisted that audit clients "talk straight" in their financial statements. Former colleagues and associates often described Andersen as opinionated, stubborn, and, in some cases, "difficult." But even his critics readily admitted that Andersen was point-blank honest. "Arthur Andersen wouldn't put up with anything that wasn't complete, 100% integrity. If anybody did anything otherwise, he'd fire them. And if clients wanted to do something he didn't agree with, he'd either try to change them or quit."1As a young professional attempting to grow his firm, Arthur Andersen quickly recognized the importance of carving out a niche in the rapidly developing accounting services industry. Andersen realized that the nation's bustling economy of the 1920s depended heavily on companies involved in the production and distribution of energy. As the economy grew, Andersen knew there would be a steadily increasing need for electricity, oil and gas, and other energy resources. So he focused his practice development efforts on obtaining clients involved in the various energy industries. Andersen was particularly successful in recruiting electric utilities as clients.By the early 1930s, Arthur Andersen & Co. had a thriving practice in the upper Midwest and was among the leading regional accounting firms in the nation. The U.S. economy's precipitous downturn during the Great Depression of the 1930s posed huge financial problems for many of Arthur Andersen & Co.'s audit clients in the electric utilities industry. As the Depression wore on, Arthur Andersen personally worked with several of the nation's largest metropolitan banks to help his clients obtain the financing they desperately needed to continue operating. The bankers and other leading financiers who dealt with Arthur Andersen quickly learned of his commitment to honesty and proper, forthright accounting and financial reporting practices. Andersen's reputation for honesty and integrity allowed lenders to use with confidence financial data stamped with his approval. The end result was that many troubled firms received the financing they needed to survive the harrowing days of the 1930s. In turn, the respect that Arthur Andersen earned among leading financial executives nationwide resulted in Arthur Andersen & Co. receiving a growing number of referrals for potential clients located outside of the Midwest.During the later years of his career, Arthur Andersen became a spokesperson for his discipline. He authored numerous books and presented speeches throughout the nation regarding the need for rigorous accounting, auditing, and ethical standards for the emerging public accounting profession. Andersen continually urged his fellow accountants to adopt the public service ideal that had long served as the underlying premise of the more mature professions such as law and medicine. He also lobbied for the adoption of a mandatory continuing professional education (CPE) requirement.Andersen realized that CPAs needed CPE to stay abreast of developments in the business world that had significant implications for accounting and financial reporting practices. In fact, Arthur Andersen & Co. made CPE mandatory for its employees long before state boards of accountancy adopted such a requirement.By the mid-1940s, Arthur Andersen & Co. had offices scattered across the eastern one-half of the United States and employed more than 1,000 accountants. When Arthur Andersen died in 1947, many business leaders expected that the firm would disband without its founder, who had single-handedly managed its operations over the previous four decades. But, after several months of internal turmoil and dissension, the firm's remaining partners chose Andersen's most trusted associate and protégé to replace him.Like his predecessor and close friend who had personally hired him in 1928, Leonard Spacek soon earned a reputation as a no-nonsense professional-an auditor's auditor. He passionately believed that the primary role of independent auditors was to ensure that their clients reported fully and honestly regarding their financial affairs to the investing and lending public.Spacek continued Arthur Andersen's campaign to improve accounting and auditing practices in the United States during his long tenure as his firm's chief executive."Spacek openly criticized the profession for tolerating what he considered a sloppy patchwork of accounting standards that left the investing public no way to compare the financial performance of different companies."2 Such criticism compelled the accounting profession to develop a more formal and rigorous rule-making process.In the late 1950s, the profession created the Accounting Principles Board (APB) to study contentious accounting issues and develop appropriate new standards. The APB was replaced in 1973 by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).Another legacy of Arthur Andersen that Leonard Spacek sustained was requiring the firm's professional employees to continue their education throughout their careers. During Spacek's tenure, Arthur Andersen & Co. established the world's largest private university, the Arthur Andersen & Co. Center for Professional Education located in St. Charles, Illinois, not far from Arthur Andersen's birthplace.Leonard Spacek's strong leadership and business skills transformed Arthur Andersen & Co. into a major international accounting firm. When Spacek retired in 1973, Arthur Andersen & Co. was arguably the most respected accounting firm not only in the United States but worldwide as well. Three decades later, shortly after the dawn of the new millennium, Arthur Andersen & Co. employed more than 80,000 professionals, had practice offices in more than 80 countries and had annual revenues approaching $10 billion. However, in late 2001, the firm, which by that time had adopted the one-word name "Andersen," faced the most significant crisis in its history since the death of its founder. Ironically, that crisis stemmed from Andersen's audits of an energy company, a company founded in 1930 that, like many of Arthur Andersen's clients, had struggled to survive the Depression.

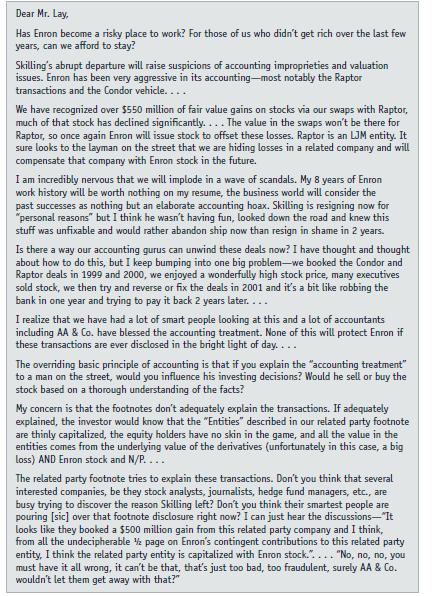

Questions1. The Enron debacle created what one public official reported was a "crisis of confidence" on the part of the public in the accounting profession. List the parties who you believe were most responsible for that crisis. Briefly justify each of your choices.2. List three types of consulting services that audit firms are now prohibited from providing to clients that are public companies. For each item, indicate the specific threats, if any, that the provision of the given service could pose for an audit firm's independence.3. For purposes of this question, assume that the excerpts from the Powers Report shown in Exhibit 3 provide accurate descriptions of Andersen's involvement in Enron's accounting and financial reporting decisions. Given this assumption, do you believe that Andersen's involvement in those decisions violated any professional auditing standards? If so, list those standards and briefly explain your rationale.4. Briefly describe the key requirements included in professional auditing standards regarding the preparation and retention of audit workpapers. Which party "owns" audit workpapers: the client or the audit firm?5. Identify five recommendations made to strengthen the independent audit function following the Enron scandal. For each of these recommendations, indicate why you support or do not support the given measure. Also indicate which of these recommendations were eventually implemented.6. Do you believe that there has been a significant shift or evolution over the past several decades in the concept of "professionalism" as it relates to the public accounting discipline? If so, explain how you believe that concept has changed or evolved over that time frame and identify the key factors responsible for any apparent changes.7. As pointed out in this case, the SEC does not require public companies to have their quarterly financial statements audited. What responsibilities, if any, do audit firms have with regard to the quarterly financial statements of their clients? In your opinion, should quarterly financial statements be audited? Defend your answer.

Step by Step Answer: