Question: Using On the Spectrum of Hydrogen by Niels Bohr -What is the main idea of the Author's argument? What is the main essence of the

Using "On the Spectrum of Hydrogen" by Niels Bohr

-What is the main idea of the Author's argument? What is the main essence of the piece?

-What ways does the author use to propose and support their argument? What is the underlying structure and evidence used?

-What are the strengths and limitations of the authors argument?

-How can the findings and documented work be simplified?

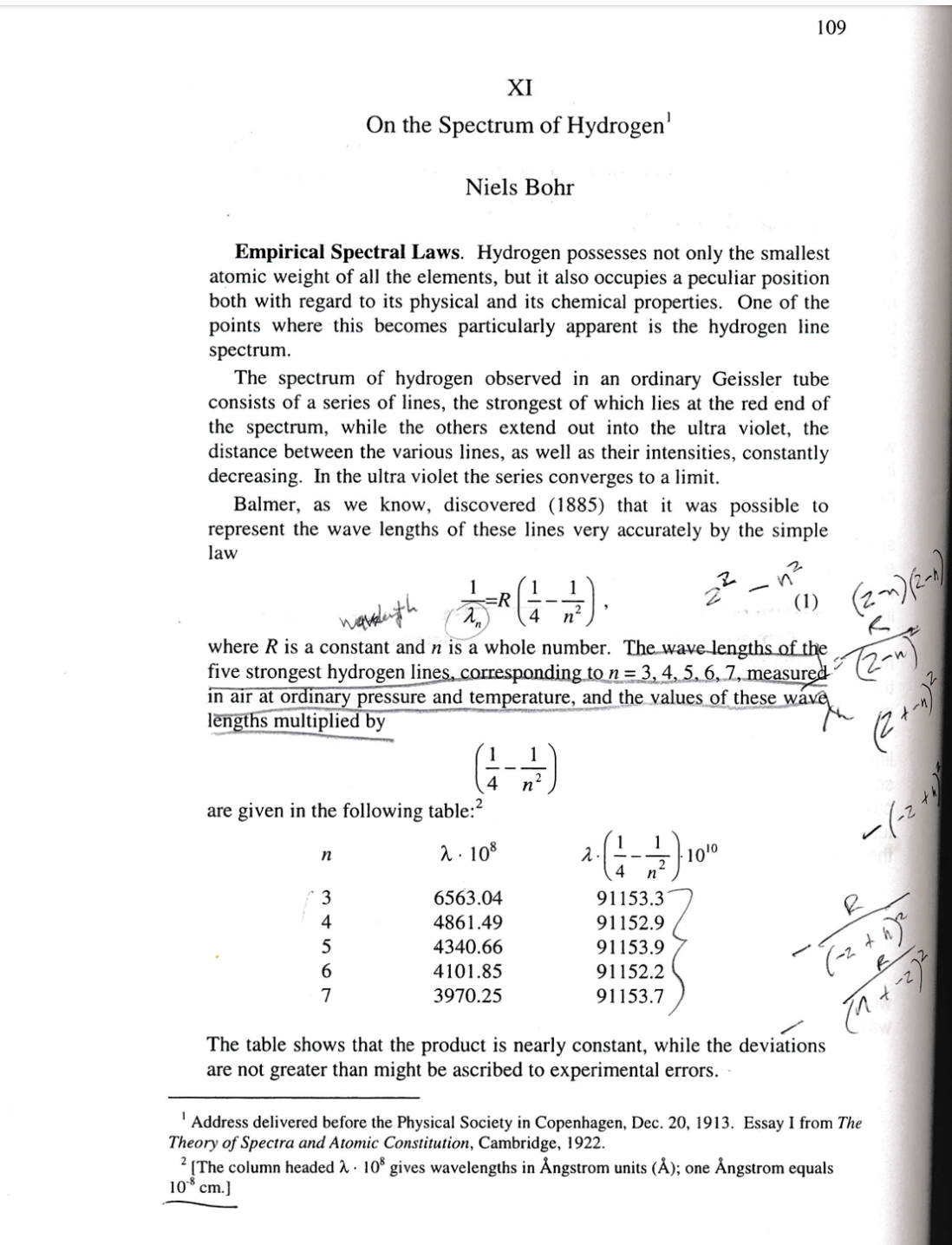

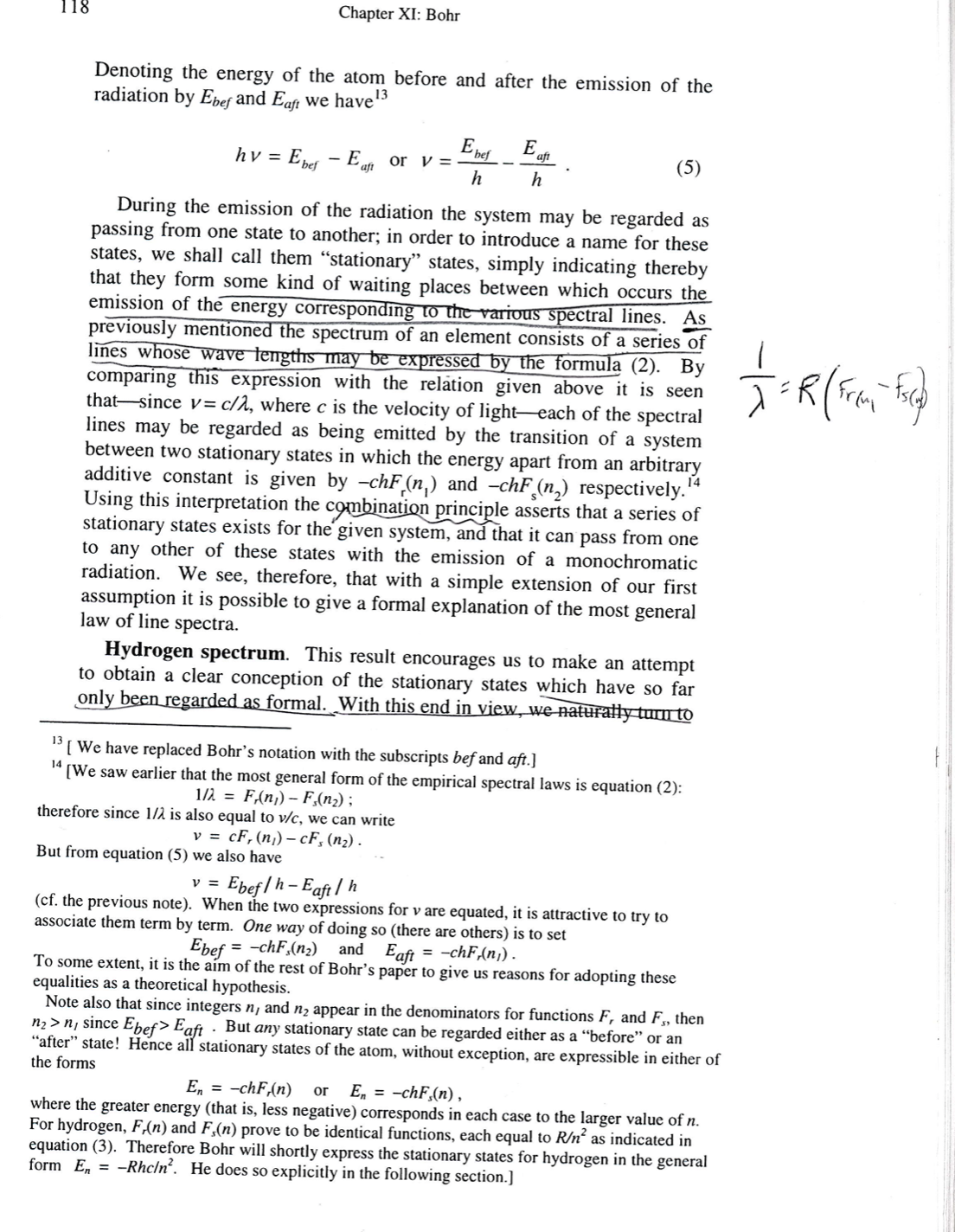

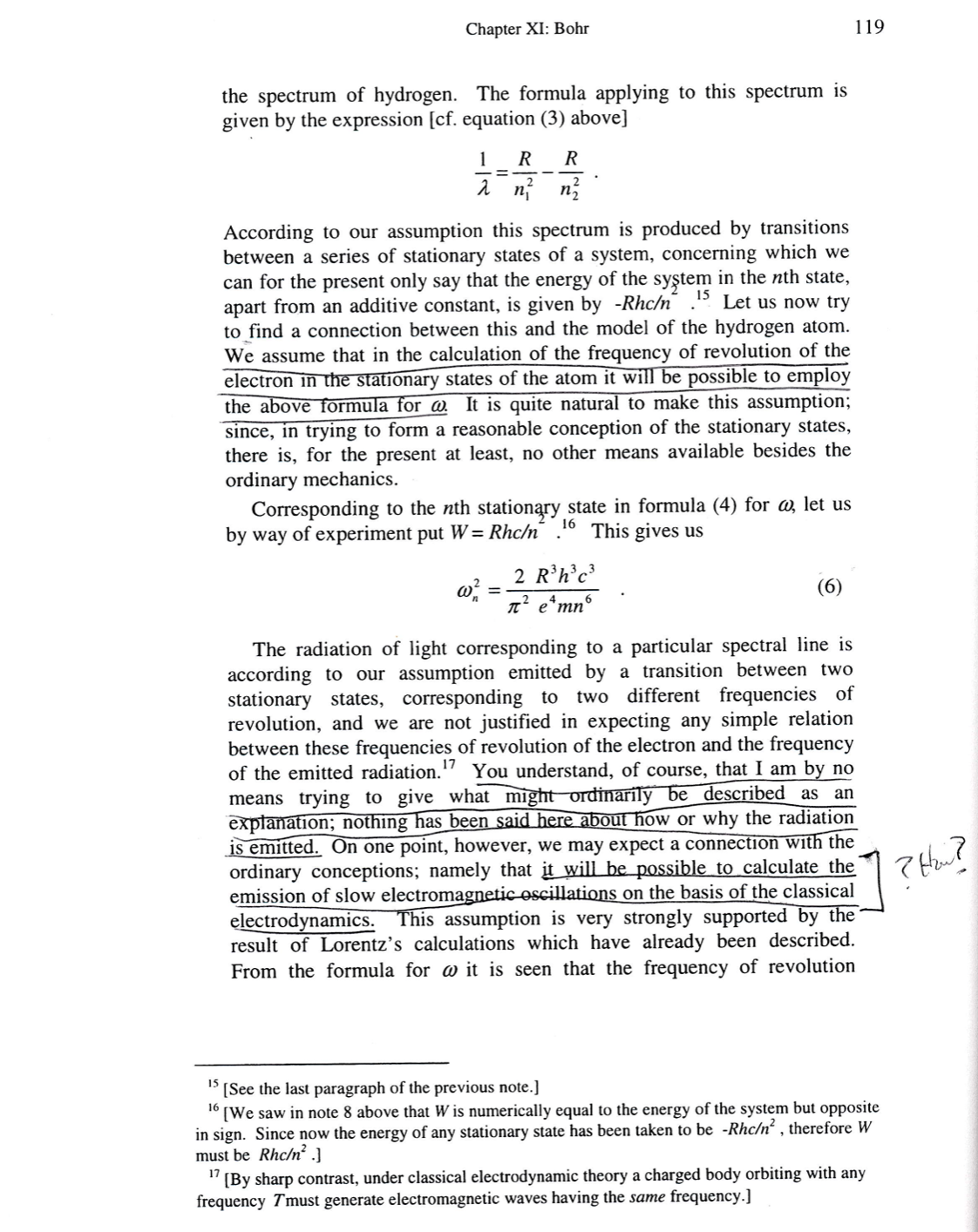

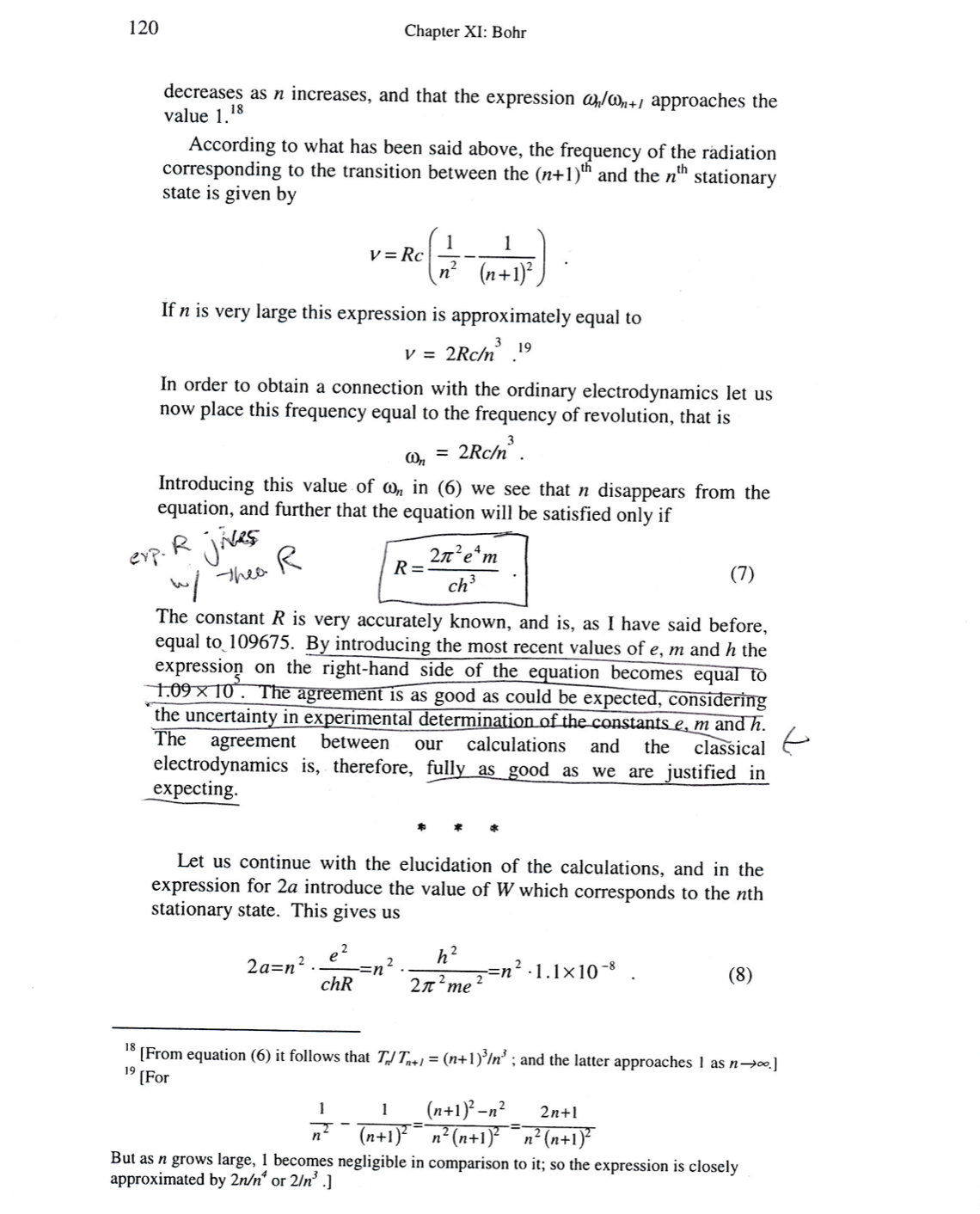

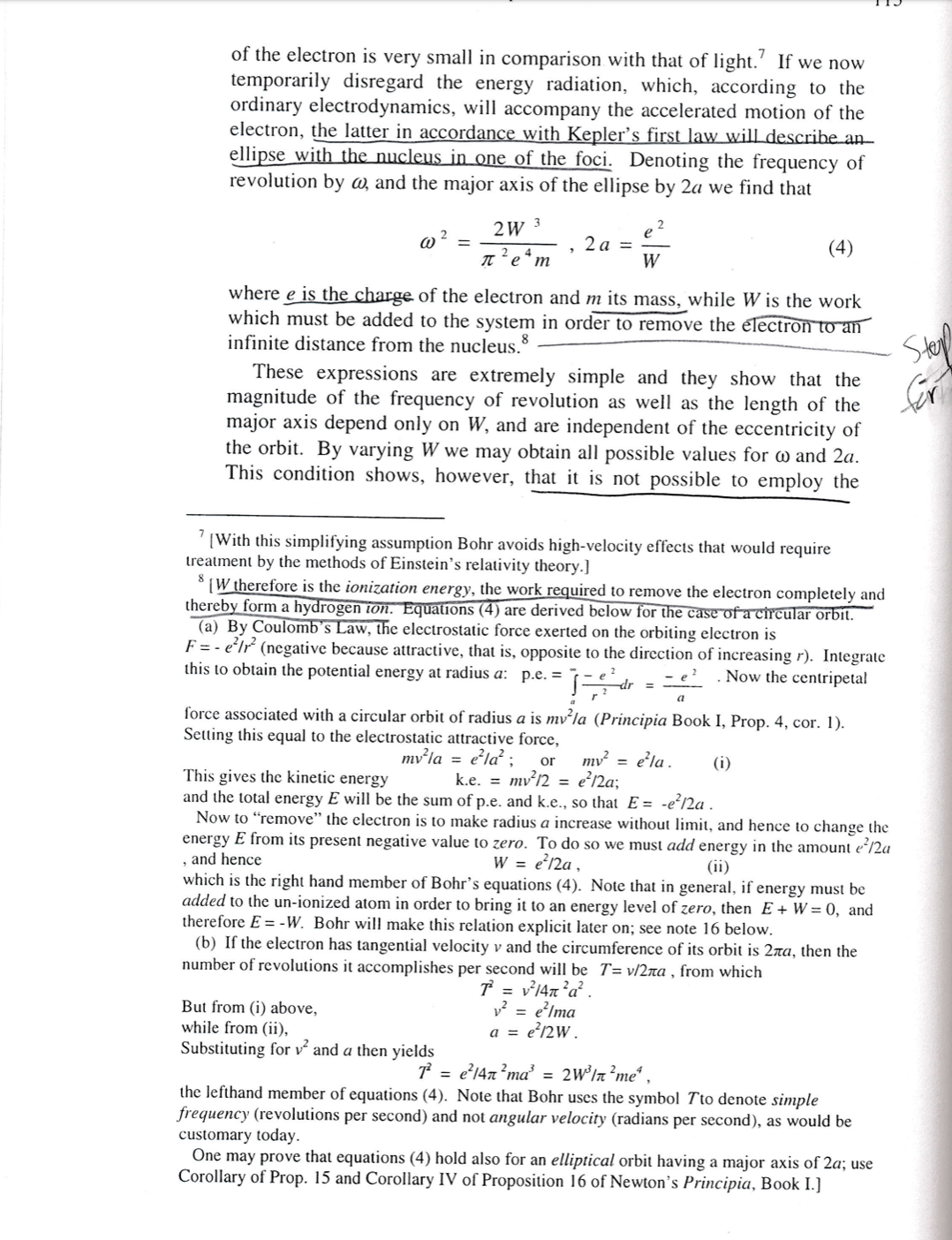

109 XI On the Spectrum of Hydrogen' Niels Bohr Empirical Spectral Laws. Hydrogen possesses not only the smallest atomic weight of all the elements, but it also occupies a peculiar position both with regard to its physical and its chemical properties. One of the points where this becomes particularly apparent is the hydrogen line spectrum. The spectrum of hydrogen observed in an ordinary Geissler tube consists of a series of lines, the strongest of which lies at the red end of the spectrum, while the others extend out into the ultra violet, the distance between the various lines, as well as their intensities, constantly decreasing. In the ultra violet the series converges to a limit. Balmer, as we know, discovered (1885) that it was possible to represent the wave lengths of these lines very accurately by the simple law (1) ( 2 n ) ( 2 - 1) where R is a constant and n is a whole number. The wave lengths of the five strongest hydrogen lines, corresponding to n = 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, measured (27 in air at ordinary pressure and temperature, and the values of these wave lengths multiplied by ( 2 4 - 1 ) 2 are given in the following table:2 - - 2 th 2 . 108 1010 6563.04 91153.3 R 4861.49 91152.9 VaUAW 4340.66 91153.9 ( - 2 + h ) 2 4101.85 91152.2 3970.25 91153.7 (n t - 2 ) The table shows that the product is nearly constant, while the deviations are not greater than might be ascribed to experimental errors. Address delivered before the Physical Society in Copenhagen, Dec. 20, 1913. Essay I from The Theory of Spectra and Atomic Constitution, Cambridge, 1922. [The column headed 2 . 10 gives wavelengths in Angstrom units (A); one Angstrom equals 10" cm.]l 18 Chapter XI: Bohr Denoting the energy of the atom before and after the emission of the radiation by EM and any we have\" E a tin/=5,\" Haw, or =ff_ 1:\" . (5) During the emission of the radiation the system may be regarded as passing from one state to another; in order to introduce a name for these states. we shall call them \"stationary" states. simply indicating thereby that they form some kind of waiting places between which occurs the emission of the energy correspon in ' ctral lines. As previously mentione t e spectrum of an element consists of a series-5F i lines w osc ss e orrnu a (2). By __ ' r comparing t IS expression with the relation given above it is seen ) ' KO?\" ist' that-since V= 001, where c is the velocity of lighteach of the spectral lines may be regarded as being emitted by the transition of a system between two stationary states in which the energy apart from an arbitrary additive constant is given by chFr(nl) and cth(n2) respectively."4 Using this interpretation the cymWe asserts that a series of stationary states exists for the given system, and that it can pass from one to any other of these states with the emission of a monochromatic radiation. We see, therefore, that with a simple extension of our first assumption it is possible to give a formal explanation of the most general law of line spectra. Hydrogen spectrum. This result encourages us to make an attempt to obtain a clear conception of the stationary states which have so far on] b e formal. With thisendi ' _____________ '3 i We have replaced Bohr's notation with the subscripts (ref and aft} "' [We saw earlier that the most general form of the empirical spectral laws is equation (2}: 1M : Pant) F5012) : therefore since 1!}. is also equal to v/c, we can write v = CFr(nl)-CF5("2) - Bul from equation (5} we also have v = Ebef/h 'Ea'l' h (cf. the previous note). When the two expressions for v are equated, it is attractive to try to associate them term by term. One way of doing so (there are others) is to set quf = -chF,(n;i) and Ea' = thAn;) . To some extent. it is the aim ofthe rest of Bohr's paper to give as reasons for adopting these equalities as a theoretical hypothesis. Note aISo that since integers in; and it; appear in the denominators for functions F , and F,, then a; > it, since Ebef' Ea . But any stationary state can be regarded either as a \"before\" or an \"after" stale! Hence al stationary states of the atom. without exception. are expressible in either of the forms E,I = \"chFAnJ or E, = c}tF,(n) , where the greater energy (that is. less negative) corresponds in each case to the larger value of n. For hydrogen, F ,(n) and F,(n) prove to be identical functions, each equal to Rz as indicated in equation (3}. Therefore Bohr will shortly express the stationary states for hydrogen in the general form E, = Rhc!nz. He does so explicitly in the following section] Chapter XI: Bohr 1 19 the spectrum of hydrogen. The formula applying to this spectrum is given by the expression [cf. equation (3) above] _R R n2 According to our assumption this spectrum is produced by transitions between a series of stationary states of a system, concerning which we can for the present only say that the energy of the system in the nth state, apart from an additive constant, is given by -Rhc ." Let us now try to find a connection between this and the model of the hydrogen atom. We assume that in the calculation of the frequency of revolution of the electron in the stationary states of the atom it will be possible to employ the above formula for @. It is quite natural to make this assumption; since, in trying to form a reasonable conception of the stationary states, there is, for the present at least, no other means available besides the ordinary mechanics. Corresponding to the nth stationary state in formula (4) for @, let us by way of experiment put W= Rhc . This gives us 12 = 2 R'h c3 (6) n e'mn The radiation of light corresponding to a particular spectral line is according to our assumption emitted by a transition between two stationary states, corresponding to two different frequencies of revolution, and we are not justified in expecting any simple relation between these frequencies of revolution of the electron and the frequency of the emitted radiation." You understand, of course, that I am by no means trying to give what might ordinarily be described as an explanation; nothing has been said here about how or why the radiation is emitted. On one point, however, we may expect a connection with the ordinary conceptions; namely that it will be possible to calculate the emission of slow electromagnetic oscillations on the basis of the classical electrodynamics. This assumption is very strongly supported by the result of Lorentz's calculations which have already been described. From the formula for @ it is seen that the frequency of revolution 15 [ See the last paragraph of the previous note.] 1 [We saw in note 8 above that W is numerically equal to the energy of the system but opposite in sign. Since now the energy of any stationary state has been taken to be -Rhc , therefore W must be Rhc' ] "[By sharp contrast, under classical electrodynamic theory a charged body orbiting with any frequency 7must generate electromagnetic waves having the same frequency.]120 Chapter XI: Bohr decreases as it increases, and that the expression (Lt/(o,1+ ,e approaches the [8 value 1. Acoording to what has been said above, the frequency of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the (n+l)"' and the n'\" stationary state is given by l l V = R0 - [n2 (32+ If] If n is very large this expression is approximately equal to 3 v = 2am: .'9 In order to obtain a connection with the ordinary electrodynamics let us now place this frequency equal to the frequency of revolution. that is (1),, = 2Rc . Introducing this value of (0,. in (6) we see that n disappears from the equation, and further that the equation will be satised only if (7') The constant R is very accurately known, and is, as I have said before, equal t0'109675. B introducing the most recent values of e, m and h the expression on the right-hand side of the e uation becomes equal to' msmmm The agreement between our calculations and the classical ) electrodynamics is, therefore, fully as good as we are justied in expecting. . 3 It Let us continue with the elucidation of the calculations, and in the expression for 2a introduce the value of W which corresponds to the nth stationary state. This gives us 1 h 2 e 2rt=n2 - 2 2 -3 =n --=n -l.lx10 . 8 Chi? 212mg: ( ) ---._,.____ '8 [From equation (6) it follows that 7;! 7],\" = (n+1 )3an ; and the latter approaches I as n9w.] 19 [For I l (\"+02 n2 2n+l From) n (n+1) 31ml)? But as It grows large, 1 becomes negligible in comparison to it; so the expression is closely approximated by Zn' or 2m; .] Chapter XI: Bohr 121 It is seen that for small values of n, we obtain values for the major axis of the orbit of the electron which are of the same order of magnitude as the values of the diameters of the atoms calculated from the kinetic theory of gases. For large values of n, 2a becomes very large in proportion to the calculated dimensions of the atoms. This, however, does not necessarily disagree with experiment. Under ordinary circumstances a hydrogen atom will probably exist only in the state corresponding to n = 1. For this state W will have its greatest value and, consequently, the atom will have emitted the largest amount of energy possible; this will therefore represent the most stable state of the atom from which the system can not be transferred except by adding energy to it from without. The large values for 2a corresponding to large n need not, therefore, be contrary to experiment; indeed, we may in these large values seek an explanation of the fact, that in the laboratory it has hitherto not been possible to observe the hydrogen lines corresponding to large values of n in Balmer's formula, while they have been observed in the spectra of certain stars. In order that the large orbits of the electrons may not be disturbed by electrical forces from the neighboring atoms the pressure will have to be very low, so low, indeed, that it is impossible to obtain sufficient light from a Geissler tube of ordinary dimensions. In the stars, however, we may assume that we have to do with hydrogen which is exceedingly attenuated and distributed throughout an enormously large region of space. Other spectra. For the spectra of other elements the problem becomes more complicated, since the atoms contain a larger number of electrons. It has not yet been possible on the basis of this theory to explain any other spectra besides those which I have already mentioned. "On the other hand it ought to be mentioned that the general laws applying to the spectra are very simply interpreted on the basis of our assumptions.... I shall not tire you any further with more details; I hope to return to these questions here in the Physical Society, and to show how, on the basis of the underlying ideas, it is possible to develop a theory for the structure of atoms and molecules. Before closing I only wish to say that I hope I have expressed myself sufficiently clearly so that you have appreciated the extent to which these considerations conflict with the admirably coherent group of conceptions which have been rightly termed the classical theory of electrodynamics. On the other hand, by emphasizing this conflict, I have tried to convey to you the impression that it may also be possible in the course of time to discover a certain coherence in the new ideas. * * *1 10 Chapter XI: Bohr As you already know, Balmer's discovery of the law relating to the hydrogen spectrum led to the discovery of laws applying to the spectra of other elements. The most important work in this connection was done by Rydberg (1890) and Ritz (1908). Rydberg pointed out that the spectra of many elements contain series of lines whose wave lengths are given. approximately by the formula : A-. R ( n + a ) ? where A and o are constants having different values for the various series, while R is a universal constant equal to the constant in the spectrum of hydrogen. If the wave lengths are measured in vacuo Rydberg calculated the value of R to be 109675. In the spectra of many elements, as opposed to the simple spectrum of hydrogen, there are several series of lines whose wave lengths are to a close approximation given by Rydberg's formula if different values are assigned to the constants A and o. Rydberg showed, however, in his earliest work, that certain relations existed between the constants in the various series of the spectrum of one and the same element. These relations were later very successfully generalized by Ritz through establishment of the "combination principle." According to this principle, the wave lengths of the various lines in the spectrum of an element may be expressed by the formula LC A - = F, (n, )- F, (n2 ) . (2) In this formula n, and n, are whole numbers, and Fi(n), F2(n),... is a series of functions of n, which may be written approximately F, (n) =- R (n + 0, )? where R is Rydberg's universal constant and a is a constant which is different for the different functions. A particular spectral line will, according to this principle, correspond to each combination of n, and n2, as well as to the functions F1, F2, .... The establishment of this principle led therefore to the prediction of a great number of lines which were not included in the spectral formulae previously considered, and in a large number of cases the calculations were found to be in close agreement with the experimental observations. In the case of hydrogen Ritz assumed that formula (1) was a special case of the general formula ["special case": Formula (1) is that special case of equation (3) in which n, has the value 4. Equation (3) is in turn that special case of equation (2) in which F, (n) and F (n) each have the form R'.]Chapter XI: Bohr 111 More general (3) for thy and therefore predicted among other things a series of lines in the infra red given by the formula 1 = R( 1 -4). n , = 3 In 1909 Paschen succeeded in observing the first two lines of this series corresponding to n = 4 and n = 5. The discovery of these beautiful and simple laws concerning the line spectra of the elements has naturally resulted in many attempts at a theoretical explanation. Such attempts are very alluring because the simplicity of the spectral laws and the exceptional accuracy with which they apply appear to promise that the correct explanation will be very simple and will give valuable information about the properties of matter. I should like to consider some of these theories somewhat more closely, several of which are extremely interesting and have been developed with the greatest keenness and ingenuity, but unfortunately space does not permit me to do so here. I shall have to limit myself to the statement that not one of the theories so far proposed appears to offer a satisfactory or even a plausible way of explaining the laws of the line spectra. Considering our deficient knowledge of the laws which determine the processes inside atoms it is scarcely possible to give an explanation of the kind attempted in these theories. The inadequacy of our ordinary theoretical conceptions has become especially apparent from the important results which have been obtained in recent years from the theoretical and experimental study of the laws of temperature radiation.* You will therefore understand that I shall not attempt to propose an explanation of the spectral laws; on the contrary I shall try to indicate a way in which it appears possible to bring the spectral laws into close connection with other properties of the elements, which appear to be equally inexplicable on the basis of the present state of the science. In these considerations I shall employ the results obtained from the study of temperature radiation as well as the view of atomic structure which has been reached by the study of the radioactive elements. Laws of temperature radiation. I shall commence by mentioning the conclusions which have been drawn from experimental and theoretical work on temperature radiation.1 12 Chapter XI: Bohr Let us consider an enclosure surrounded by bodies which are in temperature equilibrium. In this space there will be a certain amount of energy contained in the rays emitted by the surrounding substances and crossing each other in every direction. By making the assumption that the temperature equilibrium will not be disturbed by the mutual radiation of the various bodies Kirchoff (1860) showed that the amount of energy E per unit volume as well as the distribution of this energy among the various wave lengths is independent of the form and size of the space Not size + space and of the nature of the surrounding bodies and depends only on the temperature. Kirchoff's result has been confirmed by experiment, and the amount of energy and its distribution among the various wave lengths and the manner in which it depends on the temperature are now fairly well known from a great amount of experimental work; or, as it is usually expressed, we have a fairly accurate experimental knowledge of the "laws of temperature radiation." Kirchoff's considerations were only capable of predicting the existence of a law of temperature radiation, and many physicists have subsequently attempted to find a more thorough explanation of the experimental results. You will perceive that the electromagnetic theory of light together with the electron theory suggests a method of solving this problem. According to the electron theory of matter a body consists of a system of electrons. By making certain definite assumptions concerning the forces acting on the electrons it is possible to calculate their motion and consequently the energy radiated from the body per second in the form of electromagnetic oscillations of various wave lengths.... As is well known this has been done by Lorentz (1903). He calculated the emissive as well as the absorptive power of a metal for long wave lengths... Lorentz really obtained an expression for the law of temperature radiation which for long wave lengths agrees remarkably well with experimental facts. In spite of this beautiful and promising result, it has nevertheless become apparent that the electromagnetic theory is incapable of explaining the law of temperature radiation. For, it is possible to show, that, if the investigation is not confined to oscillations of long wave lengths, as in Lorentz's work, but is also extended to oscillations corresponding to small wave lengths, results are obtained which are contrary to experiment.... We are therefore compelled to assume, that the classical electrodynamics does not agree with reality, or expressed more carefully, that it can not be employed in calculating the absorption and emission of [ The "electron theory" of Lorentz: "One has been led to the conception of electrons, i.e. extremely small particles, charged with electricity, which are present in immense numbers in allradiation by atoms. Fortunately the law of temperature radiation has also successfully indicated the direction in which the necessary changes are to be sought. Even before the appearance of the papers by Lorentz and Jeans, Planck (1900) had derived theoretically a formula for the black body radiation which was in good agreement with the results of experiment. Planck did not limit himself exclusively to the classical electrodynamics, but introduced the further assumption that a system of oscillating electrical particles (elementary resonators) will neither radiate nor absorb energy continuously, as required by the ordinary electrodynamics, but on the contrary will I radiate and absorb discontinuously. The energy contained within [an elementary oscillator] at any moment is always equal to a whole multiple of the so-called quantum of energy the magnitude of which is equal to hy, where h is Planck's constant and v is the frequency [of the radiation]. In formal respects Planck's theory leaves much to be desired; in certain calculations the ordinary electrodynamics is used, while in others assumptions distinctly at variance with it are introduced without any attempt being made to show that it is possible to give a consistent explanation of the procedure used. Planck's theory would hardly have acquired general recognition merely on the ground of its agreement with experiments on black body radiation, but, as you know, the theory has also contributed quite remarkably to the elucidation of many different physical phenomena, such as specific heats, photoelectric effect, X-rays and the absorption of heat rays by gases. These explanations involve more than the qualitative assumption of a discontinuous transformation of energy, for with the aid of Planck's constant h it seems possible, at least approximately, to account for a great number of phenomena about which nothing could be said previously. It is therefore hardly too early to express the opinion that, whatever the final explanation will be, the discovery of "energy quanta" must be considered as one of the most important results arrived at in physics, and must be taken into consideration in investigations of the properties of atoms and particularly in connection with any explanation of the spectral laws in which such phenomena as the emission and absorption of electromagnetic radiation are concerned. The nuclear theory of the atom. We shall now consider the second part of the foundation on which we shall build, namely the conclusions arrived at from experiments with the rays emitted by radioactive substances. I have previously here in the Physical Society had the opportunity of speaking of the scattering of a rays in passing through thin plates, and to mention how Rutherford (1911) has proposed a theory for the structure of the atom in order to explain the remarkable and unexpected results of these experiments. I shall, therefore, only remind you that the characteristic feature of Rutherford's theory is the assumption of the existence of a positively charged nucleus inside the1 14 Chapter XI: Bohr atom. A number of electrons are supposed to revolve in closed orbits around the nucleus, the number of these electrons being sufficient to neutralize the positive charge of the nucleus. The dimensions of the nucleus are supposed to be very small in comparison with the dimensions of the orbits of the electrons, and almost the entire mass of the atom is supposed to be concentrated in the nucleus. According to Rutherford's calculations the positive charge of the nucleus [for a given element] corresponds to a number of electrons equal to about half the atomic weight [of that element]. This number coincides approximately with the number of the particular element in the periodic system and it is therefore natural to assume that the number of electrons in the atom is exactly equal to that number. This hypothesis, which was first stated by van den Broek (1912), opens the possibility of obtaining a simple explanation of the periodic system. This assumption is strongly confirmed by experiments on the elements of small atomic weight. In the first place, it is evident that according to Rutherford's theory the a particle is the same as the nucleus of a helium atom. Since the o particle has a double positive charge it follows immediately that a neutral helium atom contains two electrons. Further the concordant results obtained from calculations based on experiments as different as the diffuse scattering of X-rays and the decrease in velocity of a rays in passing through matter render the conclusion extremely likely that a hydrogen atom contains only a single electron. This agrees most beautifully with the fact that J. J. Thomson in his well-known experiments on rays of positive electricity has never observed a hydrogen atom with more than a single positive charge, while all other elements investigated may have several charges. Let us now assume that a hydrogen atom simply consists of an electron revolving around a nucleus of equal and opposite charge, and of a mass which is very large in comparison with that of the electron. It is evident that this assumption may explain the peculiar position already referred to which hydrogen occupies among the elements, but it appears at the outset completely hopeless to attempt to explain anything at all of the special properties of hydrogen, still less its line spectrum, on the basis of considerations relating to such a simple system. Let us assume for the sake of brevity that the mass of the nucleus is infinitely large in proportion to that of the electron, and that the velocity [Recall that Mendeleev (1871) had noticed that some elements appeared to belong at places in his periodic system that would be out of order with their accepted atomic weights. He went so farof the electron is very small in comparison with that of light. If we now temporarily disregard the energy radiation, which, according to the ordinary electrodynamics, will accompany the accelerated motion of the electron, the latter in accordance with Kepler's first law will describe an- ellipse with the nucleus in one of the foci. Denoting the frequency of revolution by @, and the major axis of the ellipse by 2a we find that 2W 3 , 2a = (4) where e is the charge of the electron and m its mass, while W is the work which must be added to the system in order to remove the electron to an infinite distance from the nucleus. Step These expressions are extremely simple and they show that the magnitude of the frequency of revolution as well as the length of the for major axis depend only on W, and are independent of the eccentricity of the orbit. By varying W we may obtain all possible values for w and 2a. This condition shows, however, that it is not possible to employ the "[With this simplifying assumption Bohr avoids high-velocity effects that would require treatment by the methods of Einstein's relativity theory.] [ W therefore is the ionization energy, the work required to remove the electron completely and thereby form a hydrogen ion. Equations (4) are derived below for the case of a circular orbit. (a) By Coulomb's Law, the electrostatic force exerted on the orbiting electron is F = - e'/r (negative because attractive, that is, opposite to the direction of increasing r). Integrate this to obtain the potential energy at radius a: p.e. = - - e odr = =e . Now the centripetal force associated with a circular orbit of radius a is my la (Principia Book I, Prop. 4, cor. 1). Setting this equal to the electrostatic attractive force, my la = ella ; or my? = ella . (i) This gives the kinetic energy k.e. = mv-12 = e /2a; and the total energy E will be the sum of p.e. and k.e., so that E = -e/2a . Now to "remove" the electron is to make radius a increase without limit, and hence to change the energy E from its present negative value to zero. To do so we must add energy in the amount e-/2a , and hence W = e-12a, (ii) which is the right hand member of Bohr's equations (4). Note that in general, if energy must be added to the un-ionized atom in order to bring it to an energy level of zero, then E + W= 0, and therefore E = -W. Bohr will make this relation explicit later on; see note 16 below. (b) If the electron has tangential velocity v and the circumference of its orbit is 2na, then the number of revolutions it accomplishes per second will be T= v/2na , from which T = VIAn'a . But from (i) above, = elma while from (ii), a = e-/2W. Substituting for v and a then yields 7. = e'14n'ma' = 2w 'me', the lefthand member of equations (4). Note that Bohr uses the symbol to denote simple frequency (revolutions per second) and not angular velocity (radians per second), as would be customary today. One may prove that equations (4) hold also for an elliptical orbit having a major axis of 2a; use Corollary of Prop. 15 and Corollary IV of Proposition 16 of Newton's Principia, Book I.]116 Chapter XI: Bohr above formulae directly in calculating the orbit of the electron in a hydrogen atom. For this it will be necessary to assume that the orbit of the electron can not take on all values, and in any event, the line spectrum clearly indicates that the oscillations of the electron cannot vary continuously between wide limits." The impossibility of making any progress with a simple system like the one considered here might have been foretold from a consideration of the dimensions involved; for with the aid of e and m alone it is impossible to obtain a quantity which can be interpreted as a diameter of an atom or as a frequency." , 10 If we attempt to account for the radiation of energy in the manner required by the ordinary electrodynamics it will only make matters worse. As a result of the radiation of energy. W would continually increase, and the above expressions (4) show that at the same time the frequency of revolution of the system would increase, and the dimensions of the orbit decrease." This process would not stop until the particles had approached so closely to one another that they no longer attracted each other." The quantity of energy which would be radiated away before this happened would be very great. If we were to treat these particles as geometrical points this energy would be infinitely great, and with the dimensions of the electrons as calculated from their mass (about 10 cm.), and of the nucleus as calculated by Rutherford (about 10 cm.), this energy would be many times greater than the energy changes with which we are familiar in ordinary atomic processes. It can be seen that it is impossible to employ Rutherford's atomic model so long as we confine ourselves exclusively to the ordinary electrodynamics. But this is nothing more than might have been expected. As I have mentioned we may consider it to be an established fact that it is impossible to obtain a satisfactory explanation of the experiments on temperature radiation with the aid of electrodynamics, no matter what atomic model be employed. The fact that the deficiencies of the atomic model we are considering stand out so plainly is therefore perhaps no serious drawback; even though the defects of other atomic models are much better concealed they must nevertheless be present and will be just as serious. "[Otherwise we should expect the spectroscopy pattern to show not lean lines but broad blurs covering the range of frequencies in question.] [ For example, the electrostatic unit of charge is expressed in gm -cm"-sec", while the unit of mass is gm. No combination of these units alone can yield either cm ("the diameter of an atom") or sec" ("a frequency") exclusively.] "[The electron, like any satellite losing energy, would fall toward the center and thus, by Kepler's law of periods or by Newton IV,6, would revolve with a decreased period or increased frequency. If W is the work required to remove the electron, then clearly W increases as the electron loses energy.]Chapter XI: Bohr 117 Quantum theory of spectra. Let us now try to overcome these difficulties by applying Planck's theory to the problem. It is readily seen that there can be no question of a direct application of Planck's theory. This theory is concerned with the emission and absorption of energy in a system of electrical particles, which oscillate with a given frequency per second, dependent only on the nature of the system and independent of the amount of energy contained in the system. In a system consisting of an electron and a nucleus the period of oscillation corresponds to the period of revolution of the electron. But uscilletor depends the formula (4) for @ shows that the frequency of revolution depends upon W, i.e. on the energy of the system. Still the fact that we can not on W immediately apply Planck's theory to our problem is not as serious as it might seem to be, for in assuming Planck's theory we have manifestly separate acknowledged the inadequacy of the ordinary electrodynamics and have definitely parted with the coherent group of ideas on which the latter theory is based. In fact in taking such a step we can not expect that all scillater + cases of disagreement between the theoretical conceptions hitherto employed and experiment will be removed by the use of Planck's of the transverse assumption regarding the quantum of the energy momentarily present in an oscillating system.. We stand here almost entirely on virgin ground, wave and upon introducing new assumptions we need only take care not to get into contradiction with experiment. Time will have to show to what extent this can be avoided; but the safest way is, of course, to make as few assumptions as possible. With this in mind let us first examine the experiments on temperature radiation. The subject of direct observation is the distribution of radiant energy over oscillations of the various wavelengths. Even though we may assume that this energy comes from systems of oscillating particles, we know little or nothing about these systems. No one has ever seen a Planck's resonator, nor indeed even measured its frequency of oscillation; we can observe only the period of oscillation of the radiation which is emitted. It is therefore very convenient that it is possible to show that to obtain the laws of temperature radiation it is not necessary to make any assumptions about the systems which emit the radiation except that the amount of energy emitted each time shall be equal to hv, where h is Planck's constant and v is the frequency of the radiation. Indeed, it is possible to derive Planck's law of radiation from this assumption alone, as shown by Debye, who employed a method which is a combination of that of Planck and Jeans. Before considering any further the nature of the oscillating systems let us see whether it is possible to bring this assumption about the emission of radiation into agreement with the spectral laws. If the spectrum of some element contains a spectral line corresponding to the frequency v it will be assumed that one of the atoms of the element (or some other elementary system) can emit an amount of energy hv

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts