Barny Kpf had just returned from Spoga, the international trade fair for outdoor equipment and furniture held

Question:

Barny Köpf had just returned from Spoga, the international trade fair for outdoor equipment and furniture held in Germany. Despite the global economic crisis, the results achieved at the fair had been very positive for his company, Jobek do Brasil, a Brazil-based multinational manufacturer of leisure furniture and hammocks. However, Barny must resolve some issues before he can relax and enjoy the magical sunset from the patio of his beach house in Iguape, 50 kilometers from the city of Fortaleza on Brazil’s northeast coast. The main issue is what to do with the international joint venture (IJV) forged seven years ago with the US company Hatteras Hammocks. The IJV, which began with the sale of a 49.5% interest in Barny’s company, was causing him to lose sleep. Jobek had always maintained a focus on environmental protection. The wood used to make its hammocks came from certified sources, a fact that the company had always used as a competitive advantage. The owners of Hatteras, however, had never been concerned with environmental matters. Historically, its clients were large chains such as Walmart, and the focus was on low prices.

What worried Barny was the fact that Jobek had adopted a strategy to enter international markets that had little or nothing in common with Hatteras’s strategy.

This difference had become apparent over the years of the partnership, which led to the initial terms of the IJV agreement not being fully observed. If the IJV agreement had been complied with to the letter, Hatteras would not be buying from China but from Jobek. At the same time, the contract for the exclusive distribution of Jobek products in the US market by Hatteras prevented Barny from selling to other US retailers and distributors he had met at the last trade fair. An ideal move would be to terminate the partnership, but how? Barny quickly dialed the number of his brother, Josef, the co-owner of Jobek.

The Hammock and Leisure Furniture Industry

In Brazil, production is concentrated in a few centers of small-scale manufacturers located in the Northeast, especially in the state of Ceará. In Latin America, there are several such centers in Mexico and Colombia. In Asia, especially in India and China, there are various producers of diversified outdoor leisure furniture products, including sun umbrellas, tables, chairs, swing chairs, hammocks, and other textile products for the export market. In developed economies (such as Europe and the United States), companies have emerged with strong brands. They often outsource production to or operate manufacturing plants in emerging economies.

In recent years the sector has been undergoing change on a global scale. In the 1970s and 1980s, developed economies were responsible for most of production, as well as exports of the final product. As of 1980, however, emerging economies began to play a more important role due to their cheaper labor and raw materials. As a result, companies in developed economies began to specialize in design, product development, distribution, and sales, handing over production to producers in emerging economies. In this process, the importance of agencies that verify product quality and conformity began to increase.

Social and Environmental Certifications

Preoccupation over the environment and sustainability has become increasingly apparent in the media and in public policies. Companies have come under increasing pressure to adopt the path of sustainability. However, a new problem arises. What does being responsible mean and how does it add value to a company that uses sustainability as a competitive advantage? It is well known that the cost of being environmentally responsible can be extremely high and that consumers around the world respond to it in different ways.

As a result, more certifications have been created to support a reliable sustainability and social responsibility seal.

They include the well-known ISO series, international reporting standards (such as the Global Reporting Initiative), and certifications in specific areas and sectors (such as those granted by the Forest Stewardship Council [FSC]).

The FSC is an international and independent nongovernmental organization (NGO), and its seal is the most widely recognized by other international NGOs (including the WWF, Greenpeace, and Friends of the Earth) and by the consumer market. The FSC fosters responsible forest management, aiming to preserve the forests’ main economic, environmental, and social characteristics.

The FSC provides two types of certification: Forest Management certifies organizations or agents that manage the forest in a sustainable manner in accordance with international standards and technical, economic, environmental, and social requirements. The main Chain of Custody Certificate requirement is the traceability of raw material from the forests in question (in every stage of production from extraction to the final product sold to the customer). Jobek possesses the FSC Chain of Custody Certificate, granted after an audit to ensure that only certified wood was used in its products. The certification is valid for five years, during which the firm is subject to annual inspections to ensure compliance.

Despite the FSC’s initiatives to reduce certification costs, it is still up to the contracting company to pay for the annual audits and inspections, in addition to an annual fee whose precise amount is determined by the size of the operation to be certified. Nevertheless, sustainability certificates are increasingly valued by consumers, especially in developed countries. Consequently, obtaining the FSC seal is an attractive option for Jobek do Brasil in that the seal adds value to its products through the green seal and a guarantee of high quality.

History of Jobek do Brasil

At the end of the 1980s, Jobek’s founders, two German brothers, Barny and Josef Köpf, put their enterprising idea into practice. Barny recalls:

In 1989, we started with the traditional Latin hammock, as we call it here: the hammock of Brazil and Mexico, hammocks without a rope, without a wooden framework. And so we started to import 400 hammocks as a test (from Ceará, Brazil, to Germany). We had no idea how it was going to work out but […] our neighbors liked them, since we started selling them straight from our garage […] Later we added support, accessories etc.

Today Jobek is a multinational manufacturer of hammocks and leisure furniture based in two countries.

The first base was established in 1992 in Schwangau, Germany, where Barny and Josef Köpf were born. The second was founded in 2000 in Maracanaú, in the metropolitan region of Fortaleza, Ceará, in Brazil. Today they run the Maracanaú facility, which is also where the products are manufactured. The German headquarters is in charge of quality management and product sales. In Brazil, Jobek has 250 employees in the high season and 80 in the low season. The German facility has a staff of 25.

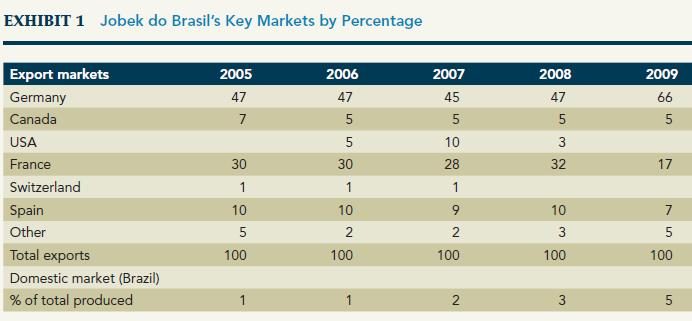

Between 2005 and 2007, Jobek’s annual export revenue averaged more than US$5 million. In 2008, however, it was less. Export profitability varies between 1% and 10% of revenue.

Germany is the main export destination, followed by France and Spain (see Exhibit 1).

Product Design Due to growing competition for mass-produced, low valueadded products, Jobek do Brasil has been focusing more on the premium niche. Some hammocks with accessories sell for more than €1,500 (US$2,000) each, thanks to innovative and exclusive design, rapid renewal of the product range, and possession of FSC certification, international safety certification (GS), and quality certification (ISO).

In addition, some of the products’ attributes are beneficial for health. Hatteras Hammocks supplies a synthetic yarn called DuraCord exclusively to Jobek do Brasil, replacing the old cotton-based yarn. In addition to being cheaper than cotton, DuraCord is more resistant and durable while maintaining cotton’s soft texture. Jobek usually protects its more innovative products by patenting them. According to the quality and purchasing manager at the south German facility, the company is concerned with the continuous development of new products and is constantly striving to stay ahead of its competitors: “We are always two years ahead of the Asians because we’re continuously coming up with new products.”

Jobek’s global value chain formed in the last few years encompasses suppliers in Brazil and China, production in Brazil, and distributors in Canada, the United States, and several countries in Europe.2 The Adoption of the FSC Certification Standard and the Supply of Certified Wood Although the FSC seal is only one certification among many, its name, brand, and reputation have become established in several markets and is the most widely recognized and respected in Europe. To promote the seal, the FSC attends trade shows and also communicates its proposal through television and magazines.

Given the characteristics of the hammock-production sector and the growing tendency of seeking environmental and social certifications, companies need to ensure the sustainability of the global value chain within which they operate to maintain the global and general consistency of the differentiation proposal based on social and environmental responsibility. However, this is no easy task. Although Jobek do Brasil has been attempting to do precisely this, its IJV with Hatteras Hammocks has raised certain issues that merit some reflection.

Certified wood suppliers are few in number and in a position to impose payment conditions almost unilaterally.

In 2008, the FSC’s representatives in Brazil admitted that “there is a problem of wood supply and, at the moment, certified forests have stopped increasing.” While Jobek do Brasil’s distributors and retailers can make use of a 180-day credit line, the company has to pay for its certified wood in cash. Barny comments on the reasons for this imbalance:

Like everything else, there are two sides to the story.

The bad side is [that] today we are dependent on FSC suppliers, which is very difficult, since we are not the only ones seeking FSC-certified wood. The Chinese, the Vietnamese, the entire world is after this wood. Unfortunately, Brazil’s rules put us at a disadvantage. When it arrives here, from the interior of Pará (Brazil), our wood is already loaded with taxes, and freight is also very expensive. The Chinese go there, to Belém (Brazil) or Curitiba (Brazil), pay for their wood for export and get it tax-free. For us, buying wood is very complicated, not to mention frustrating. We currently have only one FSC supplier. One! We are in the hands of a single supplier.

Due to growing demand for certified wood, Jobek’s quality and purchasing manager in Germany and Jobek do Brasil’s export manager admit that the company has had to turn down orders. In fact, it has been suffering legal problems due to the bottlenecks in the supply of certified wood to a major German retail chain.

Jobek has been trying to obtain alternative suppliers, in addition to certification from Brazilian agencies. However, this new certification has limited potential, since it is much less well-known than the FSC’s, which hinders the penetration of international markets.

Jobek’s owners visit their supplier regularly to verify the quality of the wood and the volume produced, which has helped increase the company’s credibility with its international distributors and clients. The wood-certification auditor firm even considers Jobek as a pioneer in its sector.

International Marketing The success of Jobek’s international hammock sales depends heavily on public awareness of the company’s FSC certification. Barny points out that because Europe keeps a very close eye on what is happening in the Amazon region, Brazilian producers with a dubious ecological pedigree cannot take part in trade fairs in Europe. “If you sell an uncertified product, there’s a good chance you’ll have Greenpeace protesting in front of your store and no one wants that.”

In this sense, the FSC’s disclosure efforts are already producing results worldwide. Jobek’s Canadian distributor believes that consumers are changing and that the green seal constitutes a definite advantage for the product.

“Previously, it was the sellers who used to tell clients about the certification, but today it’s the customers who are demanding the FSC seal.” However, Jobek’s US distributor believes that certified wood products have no market there, since both retailers and customers regard price as the most important factor in purchasing decisions. As a result, Hatteras Hammocks began to demand uncertified wood products at more competitive prices. A Hatteras representative leaves us in no doubt regarding his opinion of certified wood:

Personally, I think it’s a great idea and everyone should support it. The problem is that the people who go to Walmart or stores of that type are not willing to pay more. It’s all or nothing. You can’t have a company that’s competitive just because it’s sustainable if there’s no market for it. The thing is that everyone wants to be environmentally correct, but they don’t realize the cost and they’re not willing to pay for it.

Obviously, the emphasis on FSC certification is not enough in itself to promote Jobek’s products abroad. The product is closely associated with the Latin American culture—think of the life style of Latin American people, life in tropical regions, and beaches surrounded by palm trees. Because many people in the Northern Hemisphere envy such a life style, it makes perfect sense to exploit these concepts when promoting the product internationally.

According to Barny, this is part of the strategy:

We associated Brazilian culture with the product, which I personally think is very important. I used this strategy in Europe and at the trade fair. I said: in Brazil the culture is hammocks, the culture is coffee. What comes from Brazil?

Fruit, caipirinha, exuberance—a hammock can’t come from India or China. And we used this as a marketing tool; we put it on the packaging. These products are the most expensive line we have, they use a lot of wood, 100%

certified wood of course. The packaging with the coffee sack stamp […] was a great success.

Production and Distribution In June 2000, following investments of R$3.5 million (US$2 million), Jobek do Brasil opened a 6,900-square-meter factory in Maracanaú, which produces the entire line of hammocks, hanging chairs, and accessories. After peaking in 2004, when the facility turned out 500,000 items, production plunged in 2008 and 2009 due to dwindling US demand and the global economic crisis. As a result, Jobek reduced its direct workforce to around 80 in the low season and outsourced part of production.

Until 2008, Jobek exported almost its entire output.

It is the sector leader in Europe, with a market share of around 80%, but competition from Asia had begun to threaten its performance. Currently, it exports to more than 40 countries: more than three-quarters of production goes to Europe, whereas 15% goes to the United States, and 5% to Asia. Only 1% of output is sold in Brazil itself, mostly in the South and Southeast. Exports exceed 200,000 hammocks per year.

The International Joint Venture with Hatteras Walter R. Perkins, Jr., the founder and current CEO of Hatteras, acquired Pawleys Island and became the world’s largest hammock producer. Pawleys Island Hammocks was the oldest hammock manufacturer in the United States, which had been handcrafting cotton hammocks since its founding in 1889. Pawleys Island Rope Hammock stood for high-quality material, mixing comfort and art. One of the Hatteras’s competitive advantages is the DuraCord yarn that was specially created for it.

In view of the stronger competition, Jobek sought to increase its strength by forming an IJV. The partnership with Hatteras started in a curious way, as Barny explains:

At the beginning of 2001 and 2002, we began to take part in trade fairs in the US, in Chicago, and apparently Hatteras had heard about us. They came to our stand, talked […]. In 2002, we began selling to Walmart and Sam’s, and Hatteras were seriously upset, because someone had broken their monopoly and they lost a major client.

Hatteras’s response caught Barny and his brother by surprise:

Hatteras’s CEO told me he thought we should talk instead of becoming competitors. Then they invited me to come to their headquarters in Greenville, North Carolina, so I did, and we were really interested in establishing a partnership with them, with production in Brazil, and so were they. The two biggest companies in the US and Europe were going to get together. To create more! Two times two doesn’t make four, it makes five. That was the idea. In 2002 and 2003, the dollar was exceptionally strong, almost four reais (Brazilian currency), so it was cheap for them to produce here (in Brazil). At the time, we had very little working capital, so we decided:

“let’s sell 49.5% of Jobek to them.” And they promised to transfer all their production to Brazil, expand the factory here, the infrastructure, everything. We drew up the agreement, sold 49.5% to them and began to build a larger factory.

In addition to building the new factory, the IJV agreement also established that Hatteras would have the exclusive right to distribute Jobek’s products in the United States, whereas Jobek would distribute Hatteras and Pawleys Island brand products in Europe. Jobek products would be sold in the United States under the Jobek do Brasil name, aiming to associate Brazil’s image with the Latin American hammock made of fabric, thus differentiating it from the typical American hammocks. The Americans were visibly committed to the new venture. The son of Hatteras’s founder, Walter Perkins III, spent four weeks in Maracanaú

to help implement the basis for Hatteras hammock production, whose process is completely different from that used for the production of Jobek hammocks. In fact, the IJV got off to an excellent start. The Americans trained the Brazilian workers, who learned extremely quickly. For the Americans, who already had business ties with Chinese suppliers, Brazil was also ideal from a logistics point of view. Proximity to the United States shortened sea transport significantly: from 35 days from China to only 12 days from Pecém, Ceará, to Norfolk, Virginia.

However, much to Barny and Josef ’s surprise, in the course of the IJV, Jobek’s annual US sales plunged from US$3 million to just US$100,000. Initially, Jobek employees did not realize what was happening. Barny recalls: “We weren’t aware of it. Since they sold through a distributor, we never got the correct figure. Unfortunately, that was a mistake.” The experience left Jobek’s owners with a bitter taste because they were expecting to double the company’s revenue through the partnership. After all, they had changed the company’s entire infrastructure in Maracanaú and reserved “2,500 square meters of the factory just for them.”

But in 2003 the exchange rate started to worsen: moving from 3.6 Brazilian reais per US dollar in January 2003 to 1.75 Brazilian reais per US dollar in January 2008. It did not take long for Brazil-based production of hammocks to lose its allure for Hatteras, which ordered more products from India and China. In hindsight, Barny remarks:

They cut down on their orders and their idea was always to produce as little as possible—it wasn’t to sell our products in the US—and we began to realize that. They were not bad partners in the beginning. When you are a partner with almost 50%, when things become difficult, I expect you to remain a partner because the company is yours. Three years ago I called them and we had a meeting: “You have to place the orders or we’re going to have to change the infrastructure here. . . .” “No, but the orders are coming. . . .” And they continued acting like that […] they had come through the door but had never really entered.

The situation got so bad that Hatteras has not placed a single order since May 2008. Barny concludes: “We have the infrastructure, their things are completely idle here and we no longer communicate with Hatteras.” On the other hand, European sales of Hatteras products through Jobek’s distribution channels were not very significant either. Analyzing the Hatteras IJV in hindsight, Barny observes:

I think it was a big cultural problem. I’m German, they are Americans, and we are in Brazil. As a German, I see everything from a long-term perspective. Like this warehouse, which was built to last a lifetime. I think it’s a very different culture. And I saw a little of the difference between idealism and capitalism. I understood that it was no longer working with the Americans, not with that exchange rate. But maybe we could have come up with an alternative for another product line, adding more value. With a cheaper product I can’t produce more due to labor and infrastructure costs. I have to manufacture a product with greater added value or I have to rationalize more.

The Crisis and Future Challenges The impasse in the Hatteras–Jobek partnership was compounded by the global economic crisis, which affected people’s willingness to pay a premium for socially and environmentally responsible products, in turn penalizing those companies committed to such products. As a result, many certified wood suppliers (such as Precious Wood in Belém, Brazil) have gone out of business. Others (such as El Dorado)

are in the process of doing so. “How can we honor our commitments to our clients abroad?” Barny wonders, “We only have a few orders, but we still have to fill a container with FSC-certified wood products by the end of the season.” As if that were not enough, the crisis also affected the other side of the global value chain: “On December 22, 2008, our largest French distributor, Interproduct, went under,” Barny recalls.

It is Hatteras that is keeping Jobek’s owners awake at night. Barny and Josef both know that they would have been able to easily weather the crisis if they had not formed a IJV with the Americans and expanded the company’s infrastructure. “High fliers have the most to lose;

now we have no working capital. In addition to being stuck for capital, there is also the agreement giving Hatteras the exclusive right to distribute Jobek’s products in the US. If it were not for that, we could capitalize on our advantages with sustainable products,” Barny declares. A possible change in US environmental policy could help Jobek. “Last night, the new American president Obama said on TV that the US economy would have to grow with […] renewable energy. In this case we are two steps ahead of Hatteras, who will be our competitor because they never cared about the issue.”

At that moment, Barny remembers everything he learned from the Americans when they were in the factory in Maracanaú:

from products to how they estimated the costs. Nevertheless, it wouldn’t make any sense to compete with the same products. The products that Hatteras buys from China are cheaper. It would be smarter to compete with design, quality, innovation, with products that are not yet sold in the US. And we learned a lot from the Americans. If it weren’t for this exclusivity agreement […] they wanted to sell us their share, but since we don’t have enough working capital, how can we pay them?

Barny questions, “Working capital is hard to come by because of the global crisis. They offered to sell their 49.5% for the same price they paid when they entered the partnership.

That’s absurd,” he exclaims, outraged. “Because in the meantime they caused us a huge loss due to the lack of orders. So, how am I going to buy at the same price? You come in with no risk and you get out with no risk? Perfect, isn’t it?”

Case Discussion Questions

1. How would you evaluate the IJV between Jobek and Hatteras?

2. What was the international market strategy of Jobek? And of Hatteras?

3. ON ETHICS: What are the differences between the concept of corporate social responsibility used by Hatteras and Jobek?

4. Based on your evaluation, what should Jobek do?

5. Describe Jobek’s current competitive environment. What changes do you foresee in the future? How do you think they will influence Jobek?

Step by Step Answer: