In 1956, when Armand Hammer took over as CEO of a small company, Occidental Petroleum (Oxy), he

Question:

In 1956, when Armand Hammer took over as CEO of a small company, Occidental Petroleum (Oxy), he had a vision for the future that involved multiple businesses and dramatic growth. By the early 1980s, Hammer had achieved the growth but not the profitability that should have come with it. His search for someone to turn around his company had led him to fire seven presidents over the prior ten years—actions not seen before or since.

Finally in 1983, Hammer asked Dr. Ray R. Irani to come in and make Oxy profitable. Irani was highly regarded in the chemical industry, having graduated from the University of Southern California with a PhD in chemistry at the age of 20. He had developed 150 US patents over his career and had been president of Olin Corporation, a smaller, $2 billion chemical conglomerate, when Hammer’s headhunters called.

Attracting Irani to a company that Fortune had ranked number one out of the Five “Worst Managed” Companies in the Top 500 in 1982 was a major effort by Hammer and, ultimately, saved his company. In the early 1980s, Irani joined as Executive Vice President, Occidental Petroleum Corporation (NYSE: OXY, the parent company—in short, Oxy); and Chairman and CEO, Occidental Chemical Corporation (OxyChem, a division within Oxy). At that time, Oxy was a $14 billion firm that was a struggling alsoran in the oil industry. By 2013, when Irani retired as CEO, Oxy was consistently ranked number one on both Fortune’s “Most Admired” and “Business Sector Ranking” lists. What happened?

Starting Small

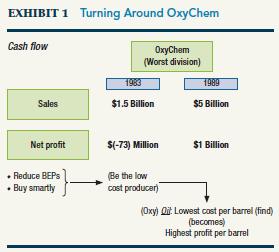

In 1983, Irani and his team of three executives who he handpicked from Olin came to Oxy. They were put in charge of OxyChem, which was Oxy’s smallest and least profitable division. While in most companies, profitimprovement programs are immediately launched in dire situations, OxyChem had no profits to improve. Shown in Exhibit 1, OxyChem was, in fact, in a negative profitability situation. When there are no profits, look for cash flow. In a commodity business, find cash flow and become the lowcost producer. That in fact was Irani’s plan for OxyChem.

By 1986, OxyChem had purchased Diamond Shamrock Chemical from Maxxus Energy. Maxxus needed cash.

OxyChem wanted to double its chlorine capacity. The deal was good for both sides. Through asset sales, cash-flow improvements, and profits, OxyChem made back the cost of that purchase within 18 months.

By 1988, OxyChem was making a much larger deal to buy Cain Chemical that focused on ethylene with a leveraged buyout (LBO) worth roughly $2.2 billion. Ethylene was

an essentially cyclical chemical but highly profitable in predictable cycles. In this case, OxyChem was competing with a much larger company to make the deal to purchase Cain. To purchase Cain, OxyChem quickly dipped into an $8 billion credit line that the banks gave Oxy (the parent company) for Hammer to use for an acquisition if he needed to act quickly. By offering $2.2 billion first, OxyChem was able to leverage its agility as a smaller company. In comparison, the larger company had to go through a capital review committee, which was more time consuming.

OxyChem’s net profit from that deal the following year was $1 billion. Fortune ranked the deal in its Top 30 Business Deals for 1988.

Saving the Parent Company

Less than two years into Irani’s tenure at OxyChem, Hammer asked him to come to Oxy’s Los Angeles headquarters to save the rest of the company. For any big deals that OxyChem made (such as Cain), Irani led the discussions. But Hammer was satisfied with the game plan and the quality of the management in place at OxyChem.

Between 1985 and 1990, Irani worked hard to improve Oxy’s profitability while waiting until 1990, when he took over as CEO, to change the overall mix of businesses for the company. For example, Iowa Beef was the largest operating division (by sales) of Oxy. It had very low profit margins.

Fortune categorized companies by whatever product category their largest operating division occupied. This made Oxy a “food company.” Explaining that to security analysts and investors was problematic.

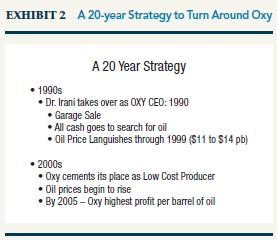

By 1990, Hammer had passed away and Irani had become CEO. His first moves were to divest divisions that did not make sense for an oil company (such as Iowa Beef) and to look forward to Oxy’s future as an oil company (Exhibit 2).

Among Oxy’s strengths was having the best oil finders in the world. Irani’s emphasis was to harness that and spend capital on finds that would eventually enable Oxy to become the lower or lowest cost producer (see Exhibit 1).

As oil prices languished in the late 1990s ($11–$14 per barrel), Oxy had invested in aging oil fields in Texas and California, which was consistent with its goal to get cost per barrel as low as possible. Oxy’s expertise at enhanced

oil recovery (EOR) positioned Oxy to maximize these opportunities.

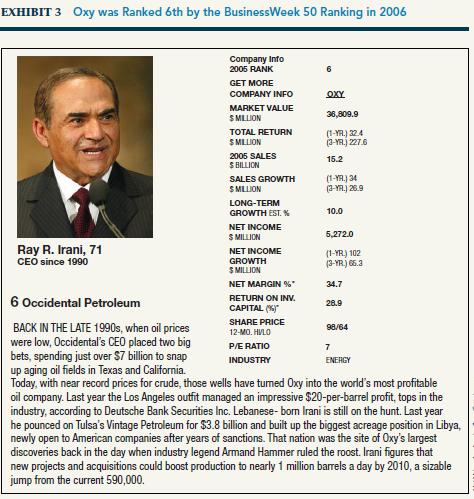

As the century turned, oil prices began to rise again. By 2005, Oxy was the world’s most profitable oil company with an impressive $20-per-barrel profit (Exhibit 3), tops in the industry.

Argentina and Agility

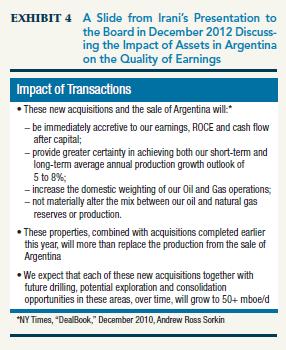

Security analysts preach about and respect “quality of earnings” concerns. While the term wears many hats, dependability of earnings or earnings growth fits most situations. A case in point is Oxy’s withdrawal from Argentina and reinvestment in its home country.

Reproduced in Exhibit 4, Irani’s December 2010 presentation to the board was entitled: “Divestment of Argentine Assets, Purchase of New US Assets, Dividend Increase.” In a refreshingly short set of slides, Irani advocated monetizing the value of its Argentine oil for cash ($2.5 billion) and investing that cash into shale oil plays in Texas and North Dakota. In other words, Irani wanted out of Argentina, where its assets could be nationalized at any time. Irani approached a Chinese oil giant, Sinopec, which was charged with acquiring oil as a priority for the Chinese government.

In 2010, 15% of foreign direct investment (FDI) in South America was China’s investment in oil, copper, and soy.

The strong implication here is that Argentina would be less inclined to nationalize the oil assets of a Chinese company, as opposed to those of an American one.

Just getting the value of Oxy’s oil assets out of Argentina was an improvement in the quality of its earnings, because it removed a threat of loss stemming from very real political risk. The withdrawal from Argentina (and sale to Sinopec) was also good timing, because in 2012, Argentina nationalized the oil company YPF by expropriating 51% of the shares belonging to its majority owner, Repsol, from Spain.

The agility that Oxy showed in finding the right buyer (Sinopec) and reinvesting the sale proceeds back into the United States was another improvement in earnings quality, because the investment back home had a high potential for growth and a substantial reduction in risk.

Oxy Today

Few CEOs of top 500 companies stay in their positions for 20 years or more. Irani was one of those. Thanks to a massive effort to divest noncore assets when he took over in 1990 and an emphasis on capital spending to find oil and gas throughout the 1990s, Oxy was positioned to reap record profits as the new century began and oil prices went back up.

Over the five-year period between 2001 and 2005, Oxy’s total debt decreased 53% while oil and gas production increased 23%. Although Oxy paid dividents every year since 1975, between 2001 and 2005, it paid $2 billion in dividends to stockholders for a total increase in shareholder value of $22.6 billion.3 Overall, the Oxy turnaround and growth strategy between 1985 and 2010 was the most successful in its history.

In the decade from 2010 to 2020, both the oil industry and Oxy saw substantial changes. In 2011, Irani retired and was succeeded by a woman who had spent her entire career at Oxy: Vicki Hollub. She became the first female CEO of a major oil company.

A mid-decade (2014 to 2016) oil price depression ($120 per barrel down to $26 per barrel) saw more than 175 companies go bankrupt. Normally, these cycles lead to consolidations.

For example, Exxon bought Mobil in 1998, and Chevron acquired Texaco in 2000.

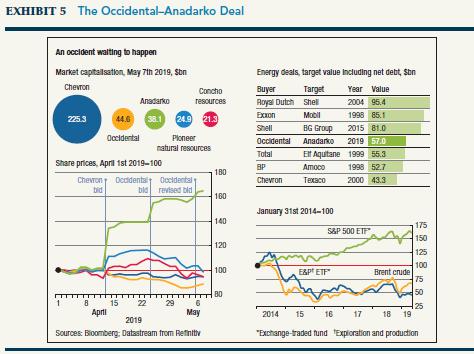

In 2019, after lengthy negotiations Oxy entered into a deal to buy Anadarko (see Exhibit 5). However, at the last

minute Chevron jumped in with a higher bid: $33 billion plus debt. To save the deal, Hollub made two trips. The first trip was to Paris where TOTAL agreed to buy $8.8 billion in North African oil and gas assets owned by Anadarko the minute the Oxy acquisition of Anadarko was finalized. This cut down on Oxy’s debt immediately. The second trip was to Omaha, Nebraska, where Warren Buffet agreed to pay $10 billion for 100,000 Oxy preferred shares, which would receive a generous 8% yearly dividend. As a result, Oxy was able to enhance its offer to Anadarko via borrowing.

Specifically, Oxy topped Chevron with a $57 billion offer plus debt. In the end, Chevron lost its bid but walked away with a check for $1 billion as a consolation prize (a penalty the Anadarko board had agreed to if it did not accept Chevron’s bid). While Oxy, through shrewd maneuvers, won the bidding war and accomplished its goals, how it can derive value from this mega deal would remain one of its leading challenges.

Case Discussion Questions

1. What were unique about Oxy’s resources and capabilities that enabled it to reap the highest profit per barrel of oil in this industry?

2. How effective did Oxy deal with the consolidations in the industry in the 2010s?

3. Although sizable, Oxy is a relatively smaller player in an industry populated by giants. How will it sail through the turmoil in the coronavirus-induced recession?

Step by Step Answer: