Two scenarios about the future of the global economy in 2050 have emerged. Known as continued globalization,

Question:

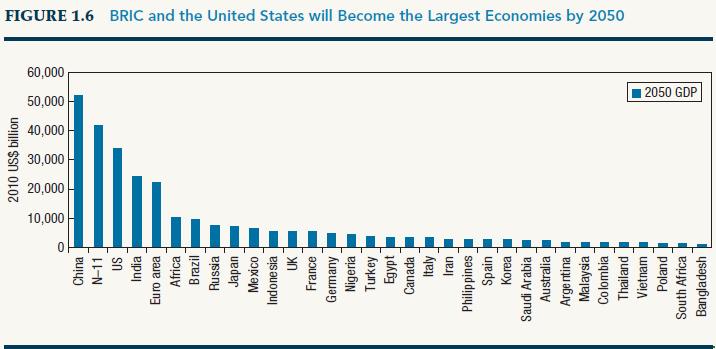

Two scenarios about the future of the global economy in 2050 have emerged. Known as “continued globalization,” the first scenario is a (relatively) rosy one. Spearheaded by Goldman Sachs, whose chairman of its Asset Management Division, Jim O’Neil, coined the term “BRIC” more than two decades ago, this scenario suggests that—in descending order—China, the United States, India, Brazil, and Russia will become the largest economies by 2050 (Figure 1.6). BRIC countries together may overtake the United States by 2025 and the Group of Seven (G-7—Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United States) by 2032, and China may individually dethrone the United States by 2026. In purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, BRIC’s share of global GDP, which rose from 18% in 2001 to 25% currently, may reach 40% by 2050.

In addition, by 2050, the Next Eleven (N-11) as a group may become significantly larger than the United States and almost twice the size of the Euro area.

Goldman Sachs’s predictions have been largely supported by other influential forecasting studies. For example, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) predicted that by 2060, China, India, and the United States will become the top three economies. The combined GDP of China and India will be larger than that of the entire OECD area. In 2011, China and India accounted for less than one-half of GDP of the G-7. By 2060, the combined GDP of China and India may be 1.5 times larger than the G-7.

India’s GDP will be a bit larger than the United States’, and China’s a lot larger.

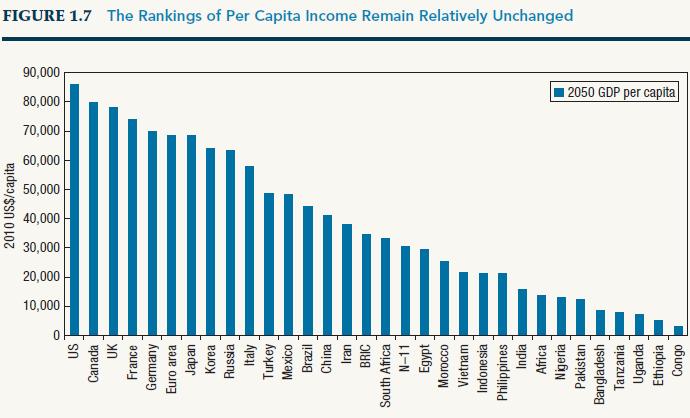

Despite such dramatic changes, one interesting constant is the relative rankings of per capita income. Goldman Sachs predicted that by 2050, the G-7 countries will still be the richest, led by the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom (Figure 1.7). Ranked eighth globally ($63,486—all dollar figures in this case refer to 2010 US dollars), Russia may top the BRIC group, with per capita income approaching that of Korea. By 2050, per capita income in China ($40,614) and India ($14,766) will continue to lag behind that in developed economies—at, respectively, 47% and 17% of the US level ($85,791). These predictions were supported by OE CD, which noted that by 2060, Chinese and Indian per capita income would only reach 59% and 27% of the US level, respectively.

Underpinning this scenario of “continued globalization” are three assumptions:

(1) emerging economies as a group will maintain strong (albeit gradually reduced) growth;

(2) geopolitical events and natural disasters (such as climate changes) will not create significant disruption;

(3) regional, international, and supranational institutions will continue to function reasonably. Globalization amplifies inequality and disruption, and this scenario envisions a path of growth that is perhaps more volatile than that of the first two decades of the 21st century. But ultimately this scenario leads to considerably higher levels of economic integration and much higher levels of incomes in countries nowadays known as emerging economies.

The second scenario can be labeled “deglobalization.” It is characterized by

(1) prolonged pandemics, recessions, high unemployment, droughts, climate shocks, disrupted food supply, and conflicts over energy (such as water wars) on the one hand;

(2) public unrest, protectionist policies, and the unraveling of certain institutions that we take for granted (such as the EU and NAFTA /USMCA)

on the other hand. As protectionism rises, global economic integration suffers. Value chains become more regional and less global. Withdrawing from operations abroad and coming home become a leading corporate movement. “Delinking”

of the US and Chinese economies would switch to high gear after the 2020 coronavirus. Numerous foreign invested factories in China would move to Southeast Asia, Africa, Mexico, and elsewhere. The United States would endeavor to make not only jetliners but also face masks An Apple smartphone, completely made in the United States, would cost more than $2,000. The upshot? Weak economic growth around the world.

During the lockdowns in 2020, people did not travel, did not eat at restaurants, and did not buy cars. A 40%–50% drop in discretionary spending could result in at least 10% reduction in GDP. The impact of the coronavirus-induced recession is worse than that of the Great Recession of 2008–2009, and the recovery has been slow. While global deintegration would harm economies worldwide, regional deintegration would harm countries of Europe. Brexit will make Britain a weaker economy. Unable to keep growing sustainably, BRICS may become “broken bricks” and fail to reach their much-hyped potential. In the 1950s and 1960s, Russian economic growth was also very impressive, fueling Soviet geopolitical ambitions that eventually turned out to be unsupportable. In the 1960s, Burma (now Myanmar), the Philippines, and Sri Lanka were widely anticipated to become the next Asian Tigers, only to falter badly. Over the long course of history, it is rare to sustain strong growth in a large number of countries over more than a decade. It is true that the first decade of the 21st century—prior to the Great Depression of 2008–2009—

witnessed some spectacular growth in BRIC and many other emerging economies. However, “failure to sustain growth has been the general rule historically,” according to a pessimistic expert.

In both scenarios, one common prediction is that global competition will heat up. Competition under the “deglobalization” scenario would be especially brutal since the total size of the “pie” will not be growing sufficiently (if not negatively). At the same time, firms would operate in partially protected markets, which result in additional costs for market penetration. Competition under the “continued globalization” scenario would also be intense, but in different ways. The hope is that a rising “tide” may be able to lift “all boats.”

CASE DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Which of the two scenarios is more plausible for the global economy in 2050? Why?

2. From a resource-based view, what should firms do to better prepare for the two scenarios?

3. From an institution-based view, what should firms do to better prepare for the two scenarios?

(For example, if they believe in “continued globalization,” they may be more interested in lobbying for reduced trade barriers. But if they believe in “deglobalization,” they may lobby for higher trade barriers.)

Step by Step Answer: