It was my first time sitting on the other side of the desk. I have been asked

Question:

It was my first time sitting on the other side of the desk. I have been asked by my Dean to serve as the Interim Director of the Marilyn Magaram Center (MMC), a Food Science, Nutrition, and Dietetics collaborative on our large state University campus. For a dozen years I have served as an “outside-the-area” advisory board member consulting in my area of expertise (health administration). I met several times with the very competent Director concerning the Center’s initiatives but my focus and involvement had only been confined to broad oversight. Now she has accepted a national position within a food service industry professional association. It is up to me to “maintain the ship” for the nine months before I begin my sabbatical. How deep will I dive into what is happening within the Center itself while I maintain my regular teaching and program director responsibilities? The extra pay being given to me while I lead the Center will be nice, and I would like to make a difference, but to do that I will need to be more actively involved in operations. Am I able to use my administrative expertise to help this Center improve or will I just be a caretaker until a new Director is recruited since food is not my thing?

Marilyn Magaram was a graduate student in Food Science and Nutrition at California State University, Northridge (CSUN). She earned her Master’s Degree in 1984 and after graduation she began teaching at CSUN. Later she opened a private practice as a Registered Dietitian, where she specialized in low-calorie, gourmet cooking. In 1989, during a trip to Australia, Marilyn died in a rafting accident. The Marilyn Magaram Center for Food Science, Nutrition, and Dietetic (MMC) was established in 1991 through the support of Marilyn’s husband, Phil, in honor of his late wife. The purpose of the Center was to provide research support and community service in the areas of food science and nutrition, while educating future professionals. Operated under the auspices of the Department of Family &Consumer Sciences in the College of Health and Human Development, the Magaram Center has engaged in a variety of nutrition and food science-related research, education, and community service projects. These activities utilize the knowledge and expertise of faculty, the energy and talents of students, and the extensive and diverse resources of the San Fernando Valley community. The Center provides a framework for collaboration among students, faculty, professionals, businesses, and community organizations in the food and nutrition field. The mission of the MMC is to enhance and promote health and wellbeing through research and education in the fields of nutrition and food science. Its vision is to be a recognized Center of Excellence in research and education in the fields of food science and nutrition in the global community. In adhering to its mission and working towards its vision, MMC has had an impact in many places in the community. It provides nutrition education and outreach through community events, health fairs and research projects in area schools, health departments, farmers’ markets, children’s centers, senior centers, and health care centers, just to name a few. It has engaged hundreds of graduate and undergraduate students in real-world, professional projects, providing them practical skills and knowledge which they cannot gain in a classroom. In this way, it ensures that the academic work can have meaningful, practical impact on all sides.To more specifically guide the Center, the MMC Advisory Board has set the following goals:

1. Promote the professional growth and development of faculty, students, and professionals in the fields of nutrition and food science.

2. Provide education related to food science, nutrition, health, and wellbeing to diverse communities.

3. Pursue scholarly projects in the fields of nutrition and food science.

4. Form (and maintain) alliances with professional organizations and community agencies to raise awareness of the critical role nutrition plays in health and wellbeing.

5. Ensure long-term viability of the Center.

MMC provides specific services to help it meet these stated goals. These include:

PEP: The MMC Professional Experiences Program (PEP) is the mechanism by which students are placed to work in MMC’s various projects. These opportunities provide “real-world”

experiences for future nutrition professionals so that they may gain knowledge and professional skills in practical settings, things that are not often taught in a classroom. Students volunteer in dietetics departments of local hospitals, promote good nutrition and fresh produce at local farmers’ markets, and plan and host educational events related to nutrition and food science on campus.

NCB: The Nutrition College Bowl (NCB) is an annual event hosted by the Center for over 15 years. Students from all over the state compete in this game show–style competition focusing on nutrition and dietetics subject areas. The goals of the NCB are to promote teamwork and leadership, enhance critical thinking skills, foster enthusiasm for learning, and create a community for nutrition scholars and future professionals.

Health Assess: MMC offers valuable health evaluation services to community members using industry standard BodPod equipment to measure body composition (% fat vs. % lean mass) and The Food Processor Nutritional Analysis software to analyze dietary intake as well as provide recipe nutrient analysis.

CSA: The Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program allows community members to purchase boxes of fresh locally grown produce each week. The boxes are delivered to campus from a local farm one day each week and are picked up the same day by CSA members. Members have the option to sign up for monthly, quarterly, or annual memberships and can choose from either a large or small box depending on their needs.

Consulting: MMC outreaches to the professional community with recipe analysis projects, which provide nutrition facts label information to food industry partners. Additionally, it offers food product analysis services that help to evaluate shelf stability (such as pH and/or flavor profiling) to companies developing new food products.

Training: The food safety management training program provides vital food safety education to students and food industry professionals. Individuals can become certified through this feesupported program, and many CSUN students who have become certified become instructors and administer the course on MMC’s behalf. The course is offered in English, Spanish, and Korean.

The Center is staffed with four people. The core team of Executive Director, Associate Director, Project Manager, and Administrative Assistant are responsible for the organizational and administrative support required to develop and ensure the success of MMC’s programs and activities.

The Executive Director directs the center on a path of continued evolution and growth. Traditionally, this position takes on the “network leader” role with more of an external focus connecting people across disciplines and organizational departments, securing grants and contracts, and developing new community partners. She interfaces with the MMC Advisory Board, comprised of industry leaders and academics, who keep MMC on track with fulfilling its mission and accomplishing its goals. In this way, she is also taking on, along with the Advisory Board, a “strategic leader” role. She also meets with top level University administration and is held accountable for MMC’s operation. She leads the MMC staff in pursuit of Center goals.

The Associate Director has more of an internal focus identified as the “operational leader.” She collaborates, once appropriate projects and opportunities for the Center are identified, on project planning, navigation of contracts, risk management, budget development, and oversight, as well as project and expense reporting. She also plays a key role in the operational management of the Center including staff and student oversight and project implementation. She plans for and coordinates new projects, ensuring they are implemented in accordance with University policy, helping to develop the specifics of contracts and budgets as well as risk management. She also provides direction and oversight for the Project Manager and Administrative Assistant to ensure that projects are properly carried out with regards to volunteer recruitment and coordination as well as tracking of activities, contacts and use of funds.

The Project Manager is also a current student in the Nutrition, Dietetics and Food Science Department at the University. As such, she is the direct link from the Center to the students that it serves. She keeps the Center abreast of the needs and concerns of the students, helping to link students to projects by identifying the types of activities and experiences that they are interested in. She directly recruits and oversees student volunteers on projects. She is responsible for developing work schedules for services as well as for the Center’s participation in outside health fairs and other events. She works with clients and PEP students to ensure that all Center services are provided in a timely and professional manner. An interesting challenge of this position is that it is continually vacated and re-staffed as students graduate from the University.

The Administrative Assistant provides administrative support to all staff in the Center. He is responsible for completing all financial paperwork as well as tracking/documenting spending for each project.

He also helps to coordinate schedules for services offered, such as the food safety manager training course and Health Assess services. He manages the office facility and maintains inventory of resources.

In order to carry out their many services and activities, the Center relies heavily on student volunteers. Some of these positions are formalized, such as the Professional Experiences Program (PEP)

students who are assigned to specific positions (i.e., overseeing the CSA program or providing Health Assess services) each semester. However, it also has student volunteers who work as needed, at health fairs or onetime community events. Other students may actually become part-time employees of the Center in which they engage in work that is grant funded. As with all academic disciplines, students in the Nutrition, Dietetics and Food Science options are encouraged to partake in professional experiences during their education. In fact, for those focusing on dietetics and planning to continue on into a dietetic internship after graduation to obtain the Registered Dietitian (RD)

credential, professional experience in the field (above and beyond that required as part of academic coursework) is required. Thus, MMC provides students with a myriad of opportunities in community, clinical, and food service settings. This helps students to apply their knowledge and skills gained in the classroom, as well as develop a sense of the specific areas in the field in which they are most interested.

Academic units can vary greatly from the very sophisticated, large grant-funded research institutes to small, specialized, distinct-focus endowed centers. All campuses seem to have them so the faculty can receive extra compensation for their research or buy out from their teaching load. Most faculty would like to concentrate on their scholarly interests not only for financial gain but also to build their personal reputation in their field of study and therefore advance their careers.

Sometimes these institutes and centers are given space (laboratories, conference room, technology, etc.) to facilitate these pursuits. This partnership, created for higher education, has many benefits not only to the faculty but also to the institution. The University’s status in the specific field researched could be enhanced. Also, securing indirect funds from certain grant awards can be used to supplement operations at the University.

The MMC is a relatively large Center for what is considered a “teaching” school. Research is becoming much more important as the state-dependency mindset is giving way to more accountability and much needed accessibility to funds to fulfill the mission. The Center was started with two generous donations that were placed into an endowment. It was never intended that these funds would actually cover direct services but that the interest they would gain would be available to use to cover operating expenses. Most of the MMC projects have needed to be self-supporting, either through fees for service or through grants written for the specific project. This has often left a gap for core operating expenses.

A large initial donation has provided our Center with the ability to continue, yet the question remains as to what happens when the funds are expended? Who will pay for the ongoing costs of engaged faculty and employed staff when the “soft” money runs out? It is becoming much more competitive to be selected for grant awards and without consistent inflowing funds, the University would have to guarantee the Center’s continued existence through budget allocations. This will just not happen in these austere times. How does our Center continue to survive when there is no money going back into operations? What can be done to make the Center sustainable into the future?

How can I lead this effort? While it is clear that the work in which our Center engages is of value to students and the surrounding community alike, the funding that supports these projects is just not properly in place. One could say of our five strategic goals listed, the one that is most in need of attention at this time is the last one: ensuring the long-term viability of the center.

MMC is held in high regard yet there is one fundamental flaw which hits most of these research-based centers. Most of the monies obtained through grants and donations are earmarked for specific things (building, equipment, projects). People and agencies like to donate or grant awards for something tangible, all the better if the donor’s name(s)

can be somehow associated with the entity/project. This is wonderful and welcomed, of course, but what is also needed for a Center like MMC is to have money to pay for operations. The Center’s mission and goals may be fulfilled through funds being provided by very generous benefactors, but the costs associated with the faculty time to coordinate both the assisting students’ pay and the supplies needed are typically how the donations and awards are allocated.

This is where management intervention can help. A complete analysis of the operations must be conducted to see what opportunities exist for improvements, which will secure the future. An evidence-based management approach is necessary so that the right things are done right (McAlearney & Kovner, 2013). Costs are to be examined and reduced. New funds that are not targeted for projects need to be obtained. A partnership needs to be created which will support the Center and allow it to accomplish its mission and goals without jeopardizing its very existence.

The Center receives no funding through the University and therefore needs to be self-sustaining. There are essentially three revenue streams:

private donations, grants, and fees collected for the services provided.

While there have been two large private donations made in the past, the donations that are received today are very small and do not serve as major support for the Center. The Center has pursued both project specific grants to support certain activities and programs as well as some grants for core operating support. Other measures must be taken to secure the Center’s position.

1. Initiation of employee evaluations: Employees of the Center have not ever had formal evaluations completed and so have received no feedback on their performance and little to no direction as far as expectations of management and goals. Initial evaluations were completed collaboratively with input from both the employee and management. The process started with a review of each job description and within that context, areas of strengths and weaknesses were identified. This process helped to clearly identify goals for each employee that met both their professional aspirations and the needs of the Center. The process has been formalized so that each employee is evaluated every 6 months.

2. Staff changes: All staff at the Center were part-time employees and the Associate Director was the only benefitted position. This left the Center with fewer staff than needed to cover basic office needs on a regular basis. An increase of the Associate Director position to 80% time (4 days per week) allowed for a redesigned role to include more responsibility for grant writing and financial management and oversight, which was required by a recent audit.

The Administrative Assistant was also given a full-time, benefitted position. This provided more office coverage during the week to support revenue-generating services. Due to these changes, the Center staff was able to take on a collaborative effort to conduct program evaluation for a multi-agency community intervention grant, which collected new revenue for the Center. Further, these changes also allowed more time for important Center management-related activities such as service contact tracking, formalizing and implementing policy and procedure, and developing training materials. Key to the success, though, was providing the Associate Director a sense of empowerment to take on the new challenges and become more independent, implementing her management changes. This embraces the philosophy of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (www.ihi.org) for building improvement capacity and stresses the importance of equipping health care professionals, at all levels, with the right (and appropriate) knowledge and skills to effect change.

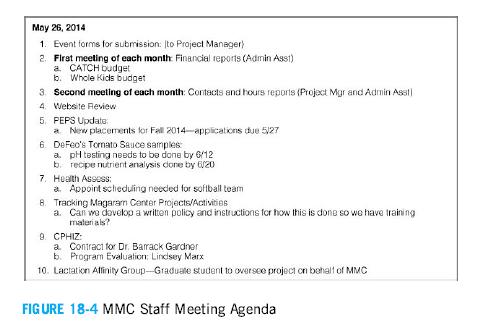

3. Staff meetings: Weekly staff meetings were implemented to ensure effective communication about ongoing projects, milestones, and planning activities among the small but active Center staff. Previously, the staff, often operating in silos, looked only at the specific project that they may be assigned. Regular meetings have facilitated communication about the many moving parts of the Center so that all projects are clear to all staff. The weekly staff meeting agenda is used as a master task list that keeps the Center on track with ongoing projects and activities. This includes standing agenda items for particular items such as activity/contact tracking and financial reports. (See Figure 18-4.)

4. Formalization of policies and procedures: As the staff has been quite small, there has been an informal system of policies and procedures dictating how the day-to-day operations are carried out. Recent changes have necessitated more formalized policies and procedures for Center operations. A recent financial audit highlighted the need for documented procedures for cash handling and reporting. The involvement of the Center in many diverse projects has necessitated standard operating procedures for fund reimbursement, event and activity tracking, volunteer management, complaint handling, and educational materials check out. Changes in Center staff positions necessitate procedures for time-off requests and employee evaluations. Standard policies and procedures have also provided excellent training materials for new volunteers as well as potential staff.

5. Comprehensive system for tracking activities and contacts:

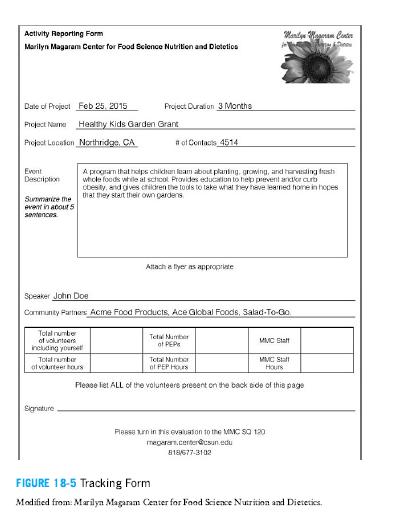

The diverse nature of the Center’s activities (research projects, health fairs, professional development workshops, CSA, NCB) has made consistent tracking and reporting of activities a challenge.

However, it is imperative for us to be able to report the types of activities that we engage in as well as the number of people that we reach in a concise and efficient manner. To address this, the task of collecting this data was specifically assigned to the Project Manager, who created a formalized policy. An Event Form was developed which allows for all pertinent information about a particular event to be recorded in a more readily usable manner. At the start of each weekly staff meeting, all current activities are reviewed and each staff member is asked to provide any and all Event Forms to the Project Manager who then enters the information into a database where it is more easily managed and reported as needed. (See Figure 18-5.)

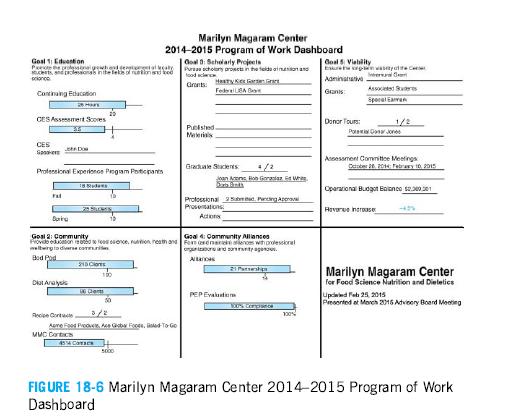

6. Dashboard reporting: In an effort to better communicate with the Advisory Board, the Center has adopted a dashboard, which clearly presents the activities of the Center and connects each back to the Center goals (listed above). For each goal set for the Center, the dashboard clearly delineates the tactics used to meet that goal and measures progress towards it. (See Figure 18-6.)

7. New partnerships: Opportunities across campus were evaluated.

Being a large urban University, collaborations could be formed to continue improvement activities. One example was engaging a health care leadership class in its team project to act as consultants on the Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program.

Another was becoming active in the IHI Open School Chapter case study reviews to enhance student learning outside of just nutrition.

8. Best practices: Many times organizations struggle to find new ways to improve. Studer (2009) states that best practices are “over discussed and underused.” Yet leaders are reluctant to ask for help.

A concerted effort was made by MMC leaders to investigate into what other discipline-specific centers on campus were doing and to meet with their leaders to share information that could be mutually beneficial. Many operational improvements were identified that helped streamline working with the entity on campus which provides accounting services.

Most of the improvements identified and implemented enhance operations but do not necessarily help the Center in its quest for sustainability. Cost reduction strategies and pursuit of alternate funding must be found if the long term objective stated is truly to be achieved. It has become increasingly important for health care organizations to understand how to estimate and manage their costs, as discussed in Chapter 10.

Modified from: Marilyn Magaram Center for Food Science Nutrition and Dietetics.

Evaluation of costs was conducted and procedures set into place which would assure the purchases being made are truly essential to continued operations. Funds that were invested but not receiving interest were examined and the determination was made to move some of the principal to interest-bearing accounts to take advantage of the increase in investment income. In addition, several other innovative strategies to obtain new sources of revenue were pursued.

1. The MMC created a partnership with the University Athletics Department to provide Health Assess services (body composition, diet analysis, and nutrition counseling) to CSUN student athletes.

A contractual agreement, which provides these services as a package at a reduced rate for each student athlete, has provided a regular revenue stream for the Center, as well as given the athletes the opportunity to improve their physical health and performance.

2. The Center developed a business plan to reach out to retail food service operators, as well as the health care, food science, and environmental health industries, to market its food safety manager certification services. Initially, the course was offered only in English but instructors have been recruited to provide the course in both in Spanish and Korean to meet the needs of the local area.

A profit sharing model has been developed that encourages instructors to market the classes to the populations that they teach and new, multi-lingual marketing materials have been developed that describe the Center’s services, including the option of having classes held onsite at their facilities. These are being distributed to restaurants, health care facilities, and food manufacturing facilities through the Center’s extensive channels of industry and community contacts. The food safety manager certification program has also been added to the local county Department of Environmental Health Approved Provider list, significantly raising the visibility of the program throughout the county.

3. The MMC connects faculty and students to relevant research experiences in a variety of community health projects. One such project is the Canoga Park Health Improvement Zone (CPHIZ), which provides education aimed at nutrition and physical activity;

chronic disease self-management; parent engagement in children’s academics; and case management services to families through four local schools. Funded by a larger private foundation, the project is overseen by a local hospital-based, community health agency and the actual services are subcontracted out to a number of other community agencies, each specializing in one of the particular services. As an example, MMC faculty members engage their students in offering the nutrition and physical activity education component. However, in an effort to generate revenue directly to the Center, the MMC also contracted for the evaluation component of the overall project. This entails MMC staff gathering reports from each of the partner agencies on the project and tracking progress towards stated goals. This is a direct fee-forservice activity, which provides sustaining revenue to the Center.

4. The continued reliance of the MMC on small government grants to fund its programs has not been a positive financial strategy as there are more agencies competing for fewer dollars. The MMC must focus on seeking contracts to provide services to the private food industry sector rather than relying on government grants.

With its existing laboratories, the MMC is able to provide sensory analysis services (food taste testing) to companies developing new food products. The MMC also has the capability to offer shelf stability and basic nutrient (sodium, fat, sugar, protein) analysis for food products. To this end, members from the local food industry have been added to the Advisory Board, who give insight into industry needs and help market services. These new Advisory Board members also can help identify potential future donors who may assist with the upkeep of existing facilities and develop new facilities as technology demands.

5. The management of large government grants has proven to be cumbersome for this small center, with very little financial gain from an operational standpoint. Thus, rather than trying to manage these large grants, the MCC focuses on subcontracting for specific services when these large grants are landed by other community partners. Examples include the evaluation services for the CPHIZ project described above. Additionally, the MMC is a subcontractor on two different large grant projects managed by outside community partners (one a county-wide obesity intervention and the other a faith-based nutrition education project). In short, the Center is focusing its efforts on maintaining high quality on numerous small projects that generate operating revenue, rather than one or two large-scale projects that supersede the limitations of its infrastructure.

My nine months are up and my last task was to shepherd a task force to choose a new permanent Director. Having two great internal candidates made it easier on me to feel I was leaving the Center in good hands. The Advisory Board Search Committee had representatives from faculty (both current and retired) and the professional community.

Helping them design and implement a criteria-based selection process guaranteed an objective decision as to who will lead MMC in the future. Looking back on my interim director role, I think I made a difference at the time, but how can these improvements be sustained under the new leader? The changes made and the plans for the future can be easily discarded by someone new coming in and wanting to set into motion their own agenda. This gets even more complicated for MMC since the Associate Director has recently decided to move to a new position outside of academia which will provide her much more growth potential. What I have decided, though, is that as long as the policies and procedures are hardwired into the system, the quality improvements are standardized, and there is assurance that the Advisory Board is actively upholding the mission, vision and goals, then I should not be concerned. It is not only money that sustains a Center, it is also processes. We like to sometimes feel it is people who make the difference, and they do; but the truth is no one is irreplaceable. The good work of the Center must be maintained no matter who is in charge.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Who would be a better Interim Director of an Academic Center:

someone who is outside the specialty area but has administrative experience or someone within the area of specialization but does not have administrative experience? Also answer for someone who has good management competencies or someone who has good leadership qualities?

2. Who are the internal stakeholders for this Center? Who are the external stakeholders? Which stakeholders should the Interim Director primarily focus on while serving in the leadership role?

3. Which leadership theory might be best for the Interim Director to use as a framework? Which leadership style might he/she use?

Why?

4. Develop the criteria to select the permanent Executive Director position using the leadership competencies and protocols listed in the chapter.

5. What unique barriers and challenges might the interim leader have when taking over for this short-term period?

6. What additional management processes or systems can the new Executive Director put into place which will help the Center achieve its goals considering today’s health care environment?

Step by Step Answer:

Introduction To Health Care Management

ISBN: 9781284081015

3rd Edition

Authors: Sharon B. Buchbinder, Nancy H. Shanks