Jerome Kerviel was born and raised in Pont-lAbbe, a small coastal village in the Brittany region of

Question:

Jerome Kerviel was born and raised in Pont-l’Abbe, a small coastal village in the Brittany region of northwestern France. His father was a blacksmith, while his mother worked as a hairdresser. Throughout his adolescent years, Kerviel dreamed of experiencing the excitement of nearby Paris, the City of Lights. Not surprisingly then, after completing undergraduate and graduate degrees in finance, the 23-year-old Kerviel accepted an entry-level position in Paris with Societe Generale, France’s second largest bank. Kerviel’s job at Societe Generale involved working in the financial institution’s “back office.” For four years, Kerviel effectively served as an internal auditor ensuring that the bank’s employees were complying with applicable company policies and procedures. His responsibilities included monitoring the bank’s securities trades to identify unauthorized trades, for example, trades that exceeded the monetary limits that had been established for individual traders.

Although polite and well-mannered, the handsome Kerviel made few friends within the bank and was thought of as “loner” by most of his co-workers. In 2004, Kerviel accomplished his goal of being promoted to a securities trader. This new position provided Kerviel an opportunity to make better use of his educational background while at the same time allowing him to escape the relative anonymity and boredom of Societe Generale’s back office. Unlike Kerviel, Societe Generale’s typical trader was a graduate of one of France’s high profi le universities and had been immediately assigned to the bank’s trading staff when hired. In France’s hierarchical society, one’s educational background and socio-economic status tend to have a disproportionate influence on not only employment opportunities but also the ability to progress rapidly within an organization once hired. Reportedly, Kerviel wanted to prove that despite his modest credentials and lower-middle class upbringing, he could complete with his more blue-blooded colleagues when he finally landed a job in Societe Generale’s trading division. After joining the trading division, Kerviel worked hard to impress his superiors.

Neighbors reported that he left his home in a Paris suburb early each morning and returned late every evening. Kerviel was so dedicated to his job that he refused to take advantage of the several weeks of vacation time that he was entitled to each year. By late 2007, Kerviel’s annual salary was approximately 100,000 euros, an impressive sum by most standards but just a fraction of what many of his fellow traders earned. In late January 2008, Daniel Bouton, Societe Generale’s chief executive officer (CEO) and chairman of the board, startled the global financial markets by announcing that over a period of just three days his bank had suffered losses of more than six billion euros on a series of unauthorized securities trades made by a “rogue trader.” According to Bouton, the trader had used his knowledge of the bank’s computer and accounting systems to circumvent the labyrinth of internal control policies and procedures designed to prevent and detect unauthorized securities trades. That individual was none other than Jerome Kerviel.

Within two days of Bouton’s announcement, Jerome Kerviel was arrested by France’s gendarmes. For forty-eight hours, law enforcement and regulatory authorities grilled the young Parisian to uncover the details of the largest fraud in the history of the banking industry. According to his attorneys, Kerviel held up extremely well during the intense interrogations. At one point, the stoic Kerviel offered one of the greatest understatements in the sordid history of crime when he casually told his interrogators that, “I just got a bit carried away.” Societe Generale was founded in 1864 during the reign of Napoleon III, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte and France’s final monarch. The bank quickly became an important source of capital for the nation’s rapidly growing economy during the final few decades of the nineteenth century. By the onset of World War II, Societe Generale operated 1,500 branches, including branches in the United States and dozens of other countries. Following World War II, France’s federal government nationalized Societe Generale to finance the reconstruction of the nation’s economic infrastructure that had been decimated by the war. In 1987, the government returned the bank to the private sector. By the turn of the century, Societe Generale had reestablished itself as one of the world’s largest and most important financial institutions. By 2007, the bank operated in almost ninety countries, had total assets of 1.1 trillion euros, and had more than 130,000 employees worldwide.

In the global banking industry, Societe Generale and several other large French banks are best known for developing a wide range of exotic financial instruments commonly referred to as derivatives. “Societe Generale pioneered equity derivatives, which allows investors to bet on future movements in stocks or markets.”2 Because of their leadership role in the development of financial derivatives, French banks control nearly one-third of the global market for those securities, a market that is measured in terms of hundreds of trillions of dollars. These same banks have also become well known for the “sophistication of their computer systems”3 that are necessary to maintain control over their financial derivatives operations. Societe Generale’s 2007 annual report revealed that nearly 3,000 employees were assigned to control and manage the risks posed by the institution’s around-the-clock and around-the-globe market trading activities. The most important of these activities are housed in the bank’s equity derivatives division, the large bank’s most profitable operating unit. The majority of the bank’s control specialists work in Societe Generale’s so-called “back office” where Jerome Kerviel began his career.......

Questions

1. Research relevant databases to identify important recent developments within France’s accounting profession, including the nation’s independent audit function. Summarize these developments in a bullet format.

2. Societe Generale maintained that because Jerome Kerviel’s “unauthorized activities” were initiated in 2007, the 6.4 billion euro loss that he incurred in January 2008 should be recorded in 2007. Do you agree with that reasoning? Why or why not?

3. Societe Generale was criticized for invoking what is often referred to as the “true and fair override” in IFRS. Is there a comparable clause or rule in GAAP? If so, identify two scenarios under which a departure from GAAP would be necessary to prevent a set of fi nancial statements from being misleading.

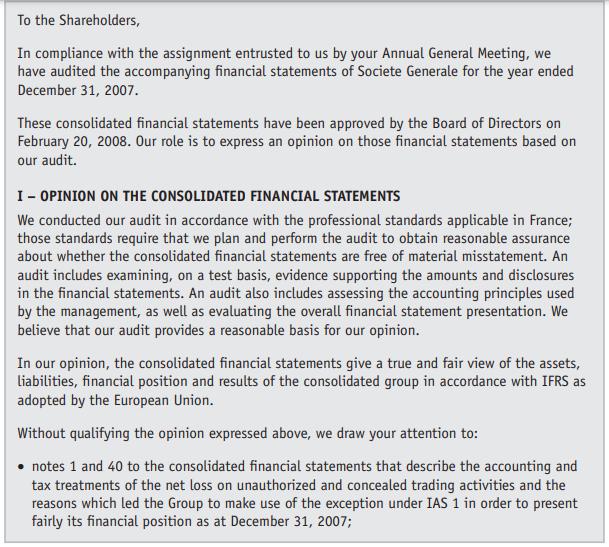

4. Compare the general format and content of the audit report shown in Exhibit 4 with the standard audit report issued under U.S. GAAS. What are the key differences between those two audit reports? Which report format is the most informative?

5. This case lists Societe Generale’s three principal internal control objectives. Compare and contrast those objectives with the primary internal control objectives discussed in GAAS.

6. Identify countries in addition to France where joint audits are performed. What economic, political, geographic, or other characteristics are common to these countries?

7. Identify audit risk factors common to a bank client. Classify these risk factors into the following categories: inherent, control, and detection. Briefly explain your classification of each risk factor that you identified.

Exhibit 4

Step by Step Answer:

Contemporary Auditing Real Issues And Cases

ISBN: 9780538466790

8th Edition

Authors: Michael C. Knapp