In January, the board of directors of the Montgomery Corporation, one of Canada's largest retail store chains,

Question:

"Ladies and gentlemen," Mr. Jackson began, after being introduced by Mr. Mohler, 'Til skip the preliminaries and get right to the point. I think that Montgomery's dividend policy is not in the best interests of our shareholders."

Observing the rather chilly stares from around the room, he hastened on: "Now, I don't mean we have a bad policy or anything like that; it's just that I think we could do an even better job of increasing our shareholders' wealth with a few small changes."

He paused for effect. "Let me explain. Up to now our policy has been to pay a constant dividend every year, increasing it occasionally to reflect the company's growth in sales and income. The problem is, that policy takes no account of the investment opportunities that the company has from year to year. In other words, this year we will use most of our net income to pay the same, or a greater, dividend than last year, even though there might be company investments available that would pay a much greater return if we committed the funds to the firm's investments instead. In effect, our shareholders are being shortchanged: they will realize perhaps a 6 percent yield on their investment as a result of receiving the dividend, when they could realize a 12 percent or higher return as a result of the company's return on its investments. I see this as a serious shortcoming in our management of the shareholders' funds."

"Now, fortunately, correcting this situation is not difficult. All we have to do is adopt what is called a residual dividend policy. That is, each year we would allocate money from income to those capital spending projects for which the return-that is, IRR-is greater than our cost of capital. Any money that is not so used in the capital budget would be paid out to the shareholders in the form of dividends. In this way we would ensure that the shareholders' money is working the hardest way it can for them."

Mr. Clarence Autry, who was also on the board of directors of the Canadian Pacific and no stranger to the world of corporate finance, broke in. "Young man," he said dryly, "your proposal ignores reality. It's not whether the shareholders are theoretically better off that counts; it's what they want that counts. You cannot tell the shareholders you're doing what's best for them by cutting the dividend; the dividend is what they want. Not only is that dividend sure money in their pockets now, but the fact that it's the same size as last time, or even higher, is a signal to them that their company is doing well and will continue to do so in the future. These decisions can't always be made on the basis of good-looking formulas from the back room, you know." Ms. Barbara Reynolds, who was the head of the directors' auditing committee, and somewhat of an accounting expert, agreed with Mr. Autry. "That's a good point, Clarence, and one that's well recognized by our competitors too. If you check, I don't think you'll find a single one of them that's cut their dividend in the last six years, even though their net income may have declined significantly. Furthermore, the whole argument is meaningless anyway, because the dividend is not really competing with the capital budget for funds. We don't turn away profitable projects in favour of paying the dividend. If there are worthy projects in which we want to invest, and we would rather use our available cash to pay the dividend, then we seek financing for the investments from outside sources. In a way, we can have our cake and eat it too." She chuckled, pleased at the analogy.

Don Jackson, however, was not to be intimidated so easily. "Yes, ma'am, what you say is true," he replied, "and I would respond that our competitors are not treating their shareholders fairly, either. Furthermore, we do seek outside financing occasionally for large projects, but there are two problems associated with doing it routinely, as you suggest. First, it might be viewed as borrowing, or issuing stock, to pay the dividend, which would cast the company in a very poor light. Second, it's more expensive to finance from outside sources than from inside due to the fees charged by the investment dealers. Therefore, I believe we should exhaust our inside sources of financing before turning to the outside."

Ms. Reynolds stood her ground. "That's all very well, but it's still not necessary to cut the dividend in order to fund the capital budget. As a last resort, if the company's cash balances were about to be drawn down too low, we could always declare a stock dividend instead of a cash dividend."

"Ladies, gentlemen," Mr. Edward Asking, the chairman, intervened, "your comments are all very perceptive, but we must move on to the business at hand. All in favour of changing to a residual dividend policy please raise your hand."

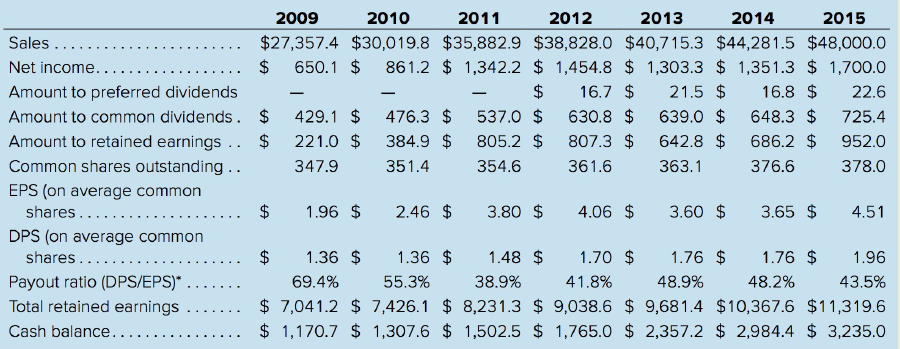

a. Refer to Table 1. Would you say that Montgomery's policy up to now has been to pay a constant dividend, with occasional increases as the company grows?

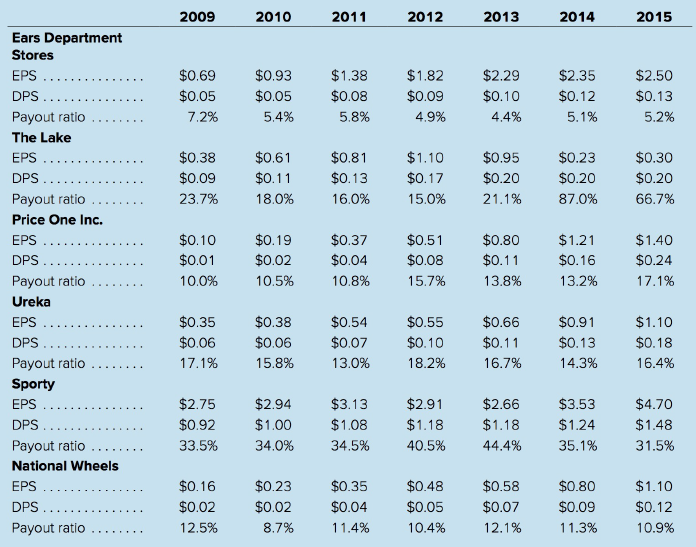

b. Refer to Table 2. What type of dividend policies would you say are being practiced by Montgomery's competitors in the retailing industry? Do you think that any firms are following a residual dividend policy?

c. Calculate the expected return to the common shareholders under the firm's present policy, given an expected dividend next year of $2.10 and a growth rate of 7.1 percent. Montgomery's stock currently sells for $35.

d. Assume that if Mr. Jackson's proposal were adopted, next year's dividend would be zero but earning growth would rise to 14 percent. What will be the expected return to the shareholders (assuming the other factors are held constant)?

e. Is the size of the capital budget limited by the amount of net income, as Mr. Jackson implies? What is the maximum size that the capital budget can be in 2016 without selling assets or seeking outside financing?

f. Mr. Jackson says the cost of the outside financing is more expensive than the cost of internal financing due to the flotation costs charged by investment dealers. Given the data you have, what would you say is the firm's cost of internal equity financing?

g. Assume Montgomery can sell bonds priced to yield 13 percent. What is the firm's aftertax cost of debt? (The tax rate is 25 percent.)

Table 1

h . Given the cost of debt and the cost of internal equity financing, why doesn't Montgomery just borrow the total amount needed to fund the capital budget and the dividend as well?

i. Do you go along with Mr. Autry's comment that it's what the shareholders want, not their total rate of return, that counts? Why or why not?

j. Barbara Reynolds suggests that if cash is needed for the capital budget , a stock dividend could be substituted for the cash dividend. Do you agree? How do you think the shareholders would react? Regardless of their reaction, is the stock dividend an equivalent substitute for the cash dividend?

k. After all is said and done, do you think the firm's dividend policy matters? If so, what do you think Montgomery's policy should be?

Table 2

The cost of debt is the effective interest rate a company pays on its debts. It’s the cost of debt, such as bonds and loans, among others. The cost of debt often refers to before-tax cost of debt, which is the company's cost of debt before taking... Expected Return

The expected return is the profit or loss an investor anticipates on an investment that has known or anticipated rates of return (RoR). It is calculated by multiplying potential outcomes by the chances of them occurring and then totaling these...

Step by Step Answer:

Foundations of Financial Management

ISBN: 978-1259024979

10th Canadian edition

Authors: Stanley Block, Geoffrey Hirt, Bartley Danielsen, Doug Short, Michael Perretta