Question: In the past, most experiments in particle physics involved stationary targets: one particle (usually a proton or an electron) was accelerated to a high energy

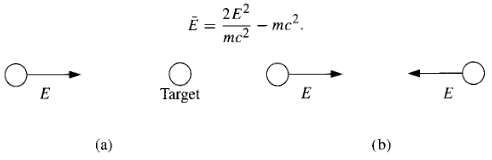

In the past, most experiments in particle physics involved stationary targets: one particle (usually a proton or an electron) was accelerated to a high energy E, and collided with a target particle at rest (Fig. 12.29a). Far higher relative energies are obtainable (with the same accelerator) if you accelerate both particles to energy E, and fire them at each other (Fig. 12.29b). Classically, the energy E of one particle, relative to the other, is just 4E (why?)????not much of a gain (only a factor of 4). But relativistically the gain can be enormous. Assuming the two particles have the same mass, m, show that suppose you use protons (mc2 = 1 GeV) with E = 30 GeV. What E do you get? What multiple of E does this amount to? (1 GeV = 109 electron volts.) [Because of this relativistic enhancement, most modem elementary particle experiments involve colliding beams, instead of fixed targets.]

E (a) IE Target = 2E mc2 - mc. - E (b) E

Step by Step Solution

3.44 Rating (173 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Classically E mv In a colliding beam experiment the relative velocity classically is twice ... View full answer

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Document Format (1 attachment)

5-P-E-E-R (34).docx

120 KBs Word File