Leland Industries is the country's fifth-largest producer of bakery and snack goods, with operations primarily located in

Question:

Late in 2015, Leland reached an agreement with a major food chain to provide private label bakery services in addition to its own products that are sold to Loblaw, Safeway, and many other grocery stores. The new private label program had significant startup costs, including new packaging techniques and the addition of 250 sales routes. Al Oliver, the vice-president of finance, believed in maintaining a balanced capital structure, and since a one million common share issue totalling $25 million in value had been offered earlier in the year, he thought this was a good time to go to the debt market. Previously, the firm's debt issues had been privately placed with insurance companies and pension funds, but Al believed this was an appropriate time to approach the public markets based on the company's recent strong performance.

He called his investment dealer and was told that the rating the firm received from S&P and DBRS would be a key variable in determining the interest rate that would be paid on the debt issue. Leland Industries intended to issue $20 million of new debt.

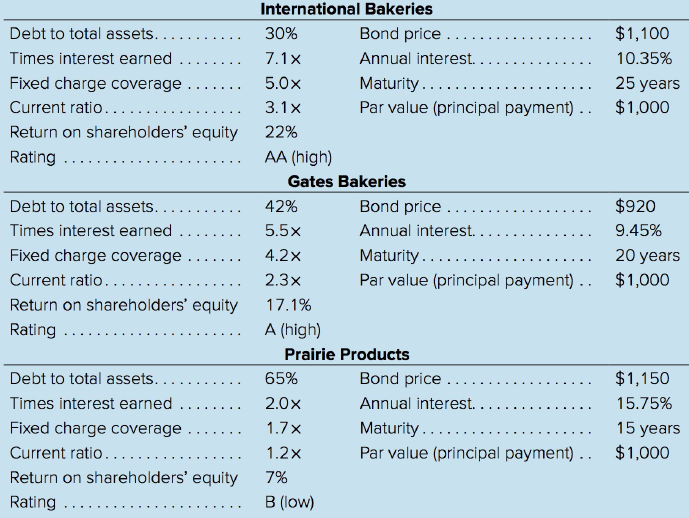

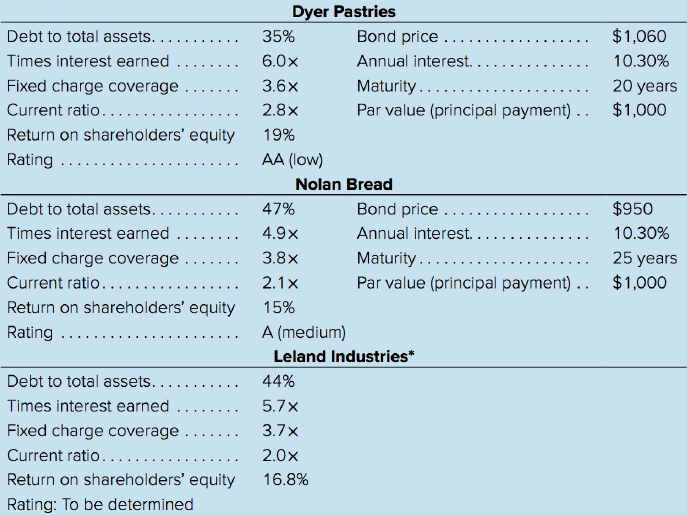

A comparison of Leland Industries to other bakeries is shown in Table 1. The other five firms all had issued debt publicly according to Ben Gilbert, who was Leland Industries' major contact at the investment dealing firm of Gilbert, Rollins, and Ross. As an alternative to a straight bond issue, Ben Gilbert suggested that the firm consider issuing floating-rate or even zero-coupon rate bonds. He said the principal advantage to the floating-rate bonds was that they could be issued at 1 1/4 percent below the going market rate for straight debt issues. Al Oliver was pleasantly surprised to hear this, and asked his investment dealer what the catch was. Al had heard too many times that "there is no such thing as a free lunch." His investment dealer explained that with a floating-rate bond the problem of interest rate changes was shifted from the borrower to the lender. To quote Ben Gilbert: Normally the risk of changes in yield to maturity is a burden or opportunity that bondholders must consider. If yields go up, bond prices of existing bonds go down, and the opposite is true if rates decline. There is a risk, and many investors do not like this risk. With a floating-rate bond the interest rate that the investor directly receives changes with market conditions and therefore the bond tends to trade at its initial par value. For example, if a bond were issued at 9 percent interest for 20 years and market rates went to 13 percent, a floating-rate bond would adjust its payment up to 13 percent, and the market value would remain at $1,000. On a straight bond issue the interest rate would remain at 9 percent, and because it is 4 percent below the market, the bond price would drop to the $700 range.

Table 1

AI Oliver quickly perceived that with a floating-rate bond he could pay 1 1/4 percent lower interest than with a fixed-rate bond, but that in future years he could not predict what his interest rates would be. He was pretty turned off by the whole idea until his investment dealer suggested that the futures and options experts at Gilbert, Rollins, and Ross could hedge this risk at a probable aftertax cost of about $120,000 per year. While he was making this point, Ben Gilbert gave AI Oliver a copy of Foundations of Financial Management by Block, Hirt, Danielsen, Short, and Perretta and suggested that he review the material on hedging at the end of Chapter 8 and in Chapter 19. AI Oliver knew that he must make a decision about the benefits and costs of floating-rate bonds.

Before the discussion was over, AI Oliver was presented with one last option. It was possible the firm might wish to issue zero-coupon rate bonds. Because no interest was paid on an annual basis and the only gain to the investor came in the form of capital appreciation, AI Oliver initially liked the idea. However, he remembered the "no free lunch" argument and asked Ben Gilbert what drawbacks there might be to this type of issue. Ben responded:

Well, AI, since you are not paying annual interest or retiring any part of the issue during its life, there can be greater risk, which may mean there is a lower rating on the issue. You, of course, know what that means in terms of a higher required yield on the bond issue. AI Oliver thought he would need to put some numbers to zero-coupon bonds as well as many of the other items that Ben Gilbert brought up. He called his young assistant in for some help.

a. Compute the yield to maturity and the aftertax cost of debt for the bonds of the other firms. Assume a tax rate of 35 percent for the firms.

b. Based on the data in Table 1, which rating and cost of debt do you think is most likely for Leland Industries?

c. If the bonds of Leland Industries carried a requirement that 5 percent of the bonds outstanding be retired each year, what would be the total amount of bonds outstanding after the third year? What would be the aftertax dollar cost of interest payments on this sum? Assume a 10 percent interest rate.

d. From a strictly dollars-and-cents viewpoint, does the floating-rate bond with the hedging approach appear to be viable?

e. Assume the zero-coupon rate bonds would be issued at a yield of 3/4 of 1 percent above a regular bond issue for 20 years. What will be the initial price of a $1,000 bond? How many bonds must be issued to raise $20 million? What is the danger in issuing the zero-coupon rate bonds?

The cost of debt is the effective interest rate a company pays on its debts. It’s the cost of debt, such as bonds and loans, among others. The cost of debt often refers to before-tax cost of debt, which is the company's cost of debt before taking... Dealer

A dealer in the securities market is an individual or firm who stands ready and willing to buy a security for its own account (at its bid price) or sell from its own account (at its ask price). A dealer seeks to profit from the spread between the...

Step by Step Answer:

Foundations of Financial Management

ISBN: 978-1259024979

10th Canadian edition

Authors: Stanley Block, Geoffrey Hirt, Bartley Danielsen, Doug Short, Michael Perretta