Question: 1. Mistakes occur sometimes when handling customer information causing a company to have to apologize to its customers. What 3 characteristics are suggested to be

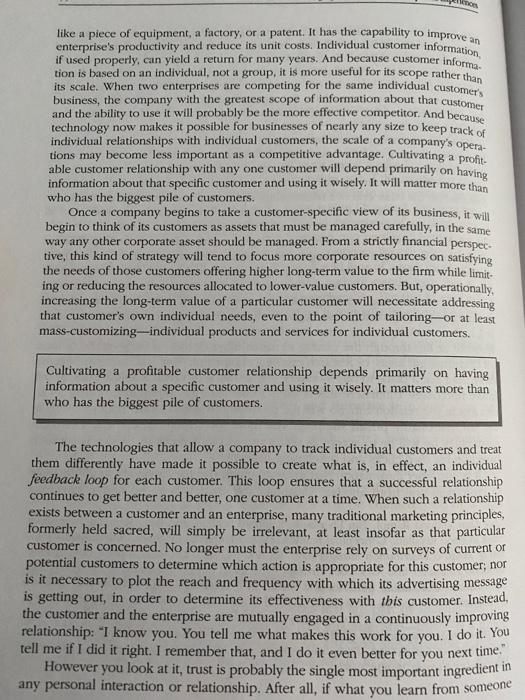

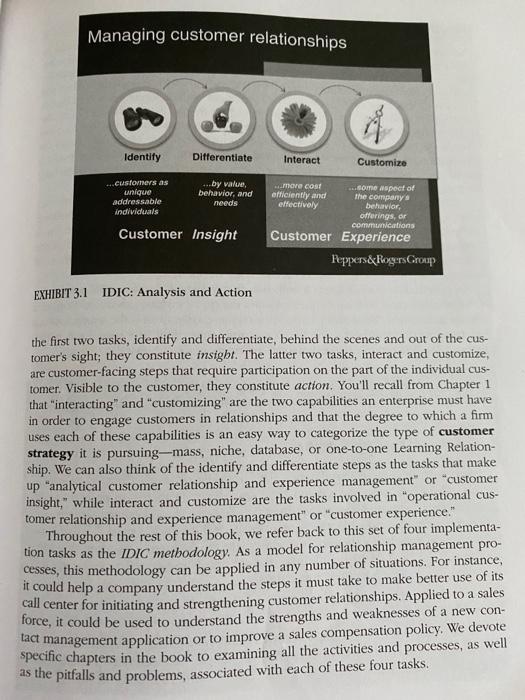

1. Mistakes occur sometimes when handling customer information causing a company to have to apologize to its customers. What 3 characteristics are suggested to be included in an apology in order to not lose customer trust? 2. What is the most important objective of managing relationships with customers? 3. Which, in your own personal view, is better to do when a customer asks you a question you have no direct knowledge of? Say "I don't know but I will find out and get back to you" OR Make up an answer that may be incorrect. an ng customer Relationships and Experience cards you carry in your wallet. But, everyone keeps asking, does that mean you have no relationship with such a company, even though it communicates with you monthly, tracks your purchases, and (at least in the best cases) proactively offers you a new card configuration based on your own personal usage pattern? Yes, there might be an element of emotion involved in this relationship, but must that always be the case? Conversely, you might have a highly emotional attachment to an enterprise, but if the enterprise itself isn't even "aware" that you exist, does this constitute anything we can call a relationship? The simple truth is that, in most cases, your relationship with a brand is analogous to your relationship with a movie star. You might love his movies, you might follow his activities avidly via social media, but will he even know who you are? It can be said to be a relationship only if the movie star some- how also acknowledges it-through personally responding to your posts or inviting you to events, for example. This is because, as we said in Chapter 2, the most basic, core feature of any relationship is mutuality. Mutual awareness of another party is a prerequisite to establishing a relationship between two parties, whether we are talking about movie star and fan or enterprise and customer. People who are emo- tionally involved with a brand, not unlike the most avid fans of a rock music group, are usually engaged in one-way affection. There's nothing wrong with this at all. One-way affection for a brand has sold a lot of merchandise. But this kind of affec- tion will be only part of a relationship if the brand is mutually involved; and in the overwhelming majority of cases, it is not So let's return to the basic, definitional characteristics of a relationship, as outlined at the beginning of Chapter 2, and try to derive from this list of charac- teristics a set of actions that an enterprise ought to take if it wants to establish relationships with its customers through deeper insights that lead to better expe- riences. A relationship is mutual, interactive, and iterative in nature, develop- ing its own richer and richer context over time. A relationship must provide an ongoing benefit to each party; it must change each party's behavior toward the other party; and it will therefore be uniquely different from one set of relation- ship participants to the next. Finally, a successful relationship will lead each party to trust the other. In fact, the more effective and successful the relationship is, from a business-building standpoint, the more it will be characterized by a high level of trust. Trust and Relationships Happen in Unison We've been looking at relationship characteristics that are part of analytic descrip- tions of the nature of a relationship while the last characteristic-trust-is a much richer term that could serve as a proxy for all the affection and favorable emotion that most of us associate with a successful relationship. In any case, what should be apparent from the outset is that we are talking about an enterprise engaging in customer-specific behaviors. That is, because relationships involve mutuality and uniqueness, an enterprise can easily have a wonderful relationship with one cus- tomer but no relationship at all with another. It can have a deep, very profitable relationship with one customer but a troubled, highly unprofitable relationship with another. An enterprise cannot have the same relationship with both Mary and Shir- ley any more than Mary can have the same relationship with both her banker and her yoga instructor. A business strategy based on managing customer relationships, then, necessar- ily involves treating different customers differently. A firm must be able to identify and recognize different, individual customers, and it must know what makes one customer different from another. It must be able to interact individually with any customer on the other end of a relationship, and it must somehow change its behav- ior to meet the specific needs of that customer, as it discovers those needs. And to build trust, it must act in the customer's best interest as well as its own. In short, in order for an enterprise to engage in the practice of treating different customers differently, it must integrate the customer into the company and adapt its products and services to the customer's own, individual needs. But as a company begins to understand the customer, interact with him, learn from him, and provide feedback based on that learning, the customer's view of what he is buying from the company will probably also begin to change. For instance, a person may shop at L.L. Bean initially to buy a sweater. But over time, he may browse the LL. Bean Web site or flip through the catalog to match other clothes to the sweater, or look for Christmas gift ideas, or research camping equipment. Now L.L. Bean has become more than just a place to buy sweaters; it is a source of valuable information about future purchases. Ultimately, this is likely to increase the importance of trust as an element in the relationship. So will the no-questions asked return policy as well as the fast, reasonably priced shipping. The more the customer trusts LL. Bean, the more likely he will be to accept its offers and recommendations (which in turn are based on his own clicks and purchasing history). It is customer information that gives an enterprise the capability to differentiate its customers one from another. Customer information is an economic asset, just See Linn Viktoria Rampl, Tim Eberhardt, Reinhard Schtte, and Peter Kenning, "Consumer Trust in Food Retailers: Conceptual Framework and Empirical Evidence," International Jour- nal of Retail & Distribution Management 40, no. 4 (2012): 254-272, Michele Gorgoglione, Umberto Panniello, and Alexander Tuzhilin, "The Effect of Context-Aware Recommendations on Customer Purchasing Behavior and Trust," in Proceedings of the Fifth AGM Conference on Recommender Systems (New York: ACM, 2011), 85-92; Peter Kenning, "The Influence of General Trust and Specific Trust on Buying Behaviour," International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 36 (2008): 461; and Ellen Garbarino and Mark Johnson, "The Dif- ferent Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and commitment in Customer Relationships." Journal of Marketing 63 (April 1999): 70-87. a like a piece of equipment, a factory, or a patent. It has the capability to improve an enterprise's productivity and reduce its unit costs. Individual customer information if used properly, can yield a return for many years. And because customer informa. tion is based on an individual, not a group, it is more useful for its scope rather than its scale. When two enterprises are competing for the same individual customers business, the company with the greatest scope of information about that customer and the ability to use it will probably be the more effective competitor. And because technology now makes it possible for businesses of nearly any size to keep track of individual relationships with individual customers, the scale of a company's opera tions may become less important as a competitive advantage. Cultivating a profit able customer relationship with any one customer will depend primarily on having information about that specific customer and using it wisely. It will matter more than who has the biggest pile of customers. Once a company begins to take a customer-specific view of its business, it will begin to think of its customers as assets that must be managed carefully, in the sam way any other corporate asset should be managed. From a strictly financial perspec- tive, this kind of strategy will tend to focus more corporate resources on satisfying the needs of those customers offering higher long-term value to the firm while limit ing or reducing the resources allocated to lower-value customers. But, operationally, increasing the long-term value of a particular customer will necessitate addressing that customer's own individual needs, even to the point of tailoring-or at least mass-customizing-individual products and services for individual customers. Cultivating a profitable customer relationship depends primarily on having information about a specific customer and using it wisely. It matters more than who has the biggest pile of customers. The technologies that allow a company to track individual customers and treat them differently have made it possible to create what is, in effect, an individual feedback loop for each customer. This loop ensures that a successful relationship continues to get better and better, one customer at a time. When such a relationship exists between a customer and an enterprise, many traditional marketing principles, formerly held sacred, will simply be irrelevant, at least insofar as that particular customer is concerned. No longer must the enterprise rely on surveys of current or potential customers to determine which action is appropriate for this customer, nor is it necessary to plot the reach and frequency with which its advertising message is getting out, in order to determine its effectiveness with this customer. Instead, the customer and the enterprise are mutually engaged in a continuously improving relationship: "I know you. You tell me what makes this work for you. I do it. You tell me if I did it right. I remember that, and I do it even better for you next time." However you look at it, trust is probably the single most important ingredient in any personal interaction or relationship. After all, if what you learn from someone Chapter 3 Customer Relationships Baste Building Mocks of IC and Trust 77 else can't be trusted, then it's not worth learning, right? And if you want to have any kind of influence with others, then what you communicate to them has to be seen as being trustworthy. Short of threat of job loss or brute force, in fact, being trustworthy is the only way your own perspectives, suggestions, persuasive appeals, or demands can have any impact on others at all. Whether you're telling or selling, cajoling or consoling, what matters most is the level of trust others have in you." Most businesses and other organizations think that they're already customer- centric and that they are basically trustworthy, even though their customers might disagree. How is the customer service at your organization Seventy-five percent of CEOs think they "provide above-average customer service," but 59 percent of consumers say they are somewhat or extremely upset with these same companies service. In one infamous study reported by Bill Price and David Jaffe, 80 percent of executives thought their companies provided superior customer service, but only 8 percent of the customers of those companies thought they received it. Even though no company can ever be certain what's in any particular custom- er's mind, companies today do have much more capable technologies for analyzing their customers' needs and protecting their interests. Sometimes, all that's required for a superior experience that leads to a valuable relationship is for a company to use its own processes to help a customer avoid a costly and preventable mistake. Peapod, the online grocery service, for instance, has software that will check with you about a likely typo before you buy something highly unusual ("Do you really want to buy 120 lemons?"). And the best companies are also using their greatly improved information tech- nology (IT) capabilities to do a better job of remembering their customers' indi- vidual needs and preferences, and then becoming smarter and more insightful over time, and using this insight to create a better customer experience. Imagine how a company might use its own database of past customer transactions for the cus- tomer's benefit. If you order a book from Amazon that you already bought from the company, you will be reminded before your order is processed. Same with iTunes. These are examples of genuinely trustable behavior. In each case, the company's database gives it a memory that can sometimes be superior to the customer's mem- ory. It would not be cheating for Amazon or iTunes simply to accept your money, thank you very much. And note that "doing the right thing," at least in this case, is mutually ben- eficial. Even as Amazon offers you the chance to opt out of a purchase you've See Ed Keller and Brad Fay. The Face-to-face Book: Wby Real Relationships Rule in a Digita 78 IDIC Process. Framework for Managing Customer Relationships and Experience already made, they also reduce the likelihood that you'll receive the book, realize to duplicate a song you already own, they are making it less likely they'll have to you already have it, and return it. And when iTunes wams you that you're about them aloud on Twitter. This is exactly how reciprocity is supposed to work as a execute a labor-intensive and costly refund process, or that you'll think badly of win-win. In addition to the company-customer feedback loop involving clickthroughs and purchasing history, customer satisfaction surveys, questionnaires, and even cus tomer complaints across devices, a company may also gain insight about customer tions with other customers (see Chapter 8). A company has the opportunity to learn wants, needs, or expectations by monitoring customers' social media communica from conversations taking place in online social networks. This is highly important for companies trying to build relationships with their customers for three main reasons: 1. Social networks have high impact on the flow and quality of information. As opposed to a belief in impersonal and generic sources, customers prefer to rely on peers and their perspectives. 2. Information within networks disseminates quickly across devices and impacts word-of-mouth referrals and recommendations. 3. Social networks of customers also carry the implication of trust as the informa- tion becomes more personalized with experience and familiarity of the mem- bers of the social network. 4. Even beyond known members of a network, the total strangers, who are viewed as peers, who rate products and services on Web sites, are also trusted as refer- ences and recommenders for or against products, making Amazon.com one of the largest social networking sites in the world. The secret to keeping and growing a single customer forever is this feedback loop. Creating it requires the customer's own participation and effort along with his trust in the company that's getting his information. It is the effort on the part of the customer that results in a better product or service than the customer can get anywhere else from any company that is not so far up a particular customer's learning curve. The successive interactions that characterize such a Learning Rela- tionship ultimately result in the enterprise's capability to make its products and ser- vices highly valuable to an individual customer; indeed, the Learning Relationship. because it is unique to that customer, and because it has been formed in large part from the customer's own participation, can become irreplaceably valuable to that customer, ensuring the customer's long-term loyalty and value to the enterprise. Ser Mark Cur Customer Relations des Building Blocks of and Trus 79 Or wherever IDIC Four Implementation Tasks for Creating and Managing Customer Experiences and Relationships Setting up and managing individual customer relationships can be broken up into four interrelated implementation tasks. These implementation tasks are based on the unique, customer-specific, and iterative character of such relationships. We list them roughly in the sequence in which they will likely be accomplished, although as we see later in this book, there is a great deal of overlap among these implemen- ration tasks (e.g., an enterprise might use its Web presence primarily to attract the most valuable customers and identify them individually rather than as a customer interaction platform), and there may be good reason for accomplishing them in a different order: 1. Identify customers. Relationships are n enterprise must be able to rec possible only with individuals, not with back, in person, by phone, online, or markets, segments, populations Therefore, the first task in setting up a relationship is to identify, individually, the party at the other end of the relationship. Many companies don't really know the identities of many of their customers, so for them this first step is difficult but absolutely crucial. For all companies, the "identify" task also entails organizing the enterprise's various information resources so that the company can take a customer-specific view of its business. It means ensuring that the company has a mechanism for tagging individual customers not just with a product code that identifies what's been sold but also with a customer code that identifies the party that the enterprise is doing business with-the party at the other end of the mutual relationship. An enter- prise must be able to recognize a customer when he comes back, in person, by phone, online, by mobile app, or wherever. Moreover, enterprises need to "know" and remember each customer in as much detail as possible-including the habits, preferences, and other characteristics that make each customer unique. When you log in to Cabela's online account, the company knows about your last order, because you've been identified. 2. Differentiate customers. Knowing how ustomers represent different levels customers are different allows a company have different needs from the enterprise. (a) to focus its resources on those cus- The customer's needs drive his behavior, tomers who will bring in the most value and his behavior is what the enterprise for the enterprise, and (b) to devise and observes in order to estimate his value, implement customer-specific strategies designed to satisfy individually different customer needs and improve each customer's experience. Customers represent different levels of value to the enterprise, and they have different needs from the IDIC Process: A Framework for Managing Customer Relationships and Experience 80 enterprise. The customer's needs drive his behavior, and his behavior is what the Customer grouping the process by which customers are clustered into catego- enterprise observes in order to estimate his value. Although not a new concept, ries based on a specified variable-is a critical step in understanding and profit an enterprise in categorizing its customers by both their value to the firm and ably serving customers. Specifically, the "customer differentiation" task involves by what needs they have. Some call centers constantly change the order to serve based on the different values of those customers who are waiting on hold Although it would be ideal to answer every call on the second ring, when that's not possible, it would be better to vault the customers keeping you in business ahead of the customers of lower value. In most contact centers, this reshuffling is not at all apparent to customers. 3. Interact with customers. Enterprises must improve the effectiveness of their Ashould pick up where the last one interactions with customers. Each succes- left off. And a company should never sive interaction with a customer should ask the same question twice. take place in the context of all previous interactions with that customer. A bank may ask one question in each month's electronic statement, and next month's question may depend on last month's answer. A conversation with a customer should pick up where the last one left off. Effective customer interactions pro- vide better insight into a customer's needs and don't waste a customer's time by asking the same question more than once, even in different parts of the organization 4. Customize treatment. The enterprise should tailor the customer's experience, Th he enterprise should adapt some based on that individual's needs and aspect of its behavior toward a cus- value, to make it more relevant to the tomer, based on that individual's needs and value. customer, to make the customer's life a little easier and better. To engage a cus- tomer in an ongoing Learning Relationship, an enterprise needs to adapt its behavior to satisfy the customer's expressed needs. Doing this might entail mass- customizing a product or tailoring some aspect of its service. This customization could involve the format or timing of an invoice or how a product is packaged. This IDIC process implementation model can also be broken into two broad Categories of activities: insight and action (see Exhibit 3.1). The enterprise conducts Marisa Peacock, "Demand for Tailored Custom Managing customer relationships Identify Differentiate Interact Customize customers as unique addressable individuals ...by value behavior, and needs wemove cost ...some aspect of efficiently and the company effectively behavior, offerings, or communications Customer Experience Peppers&Rogers Group Customer Insight EXHIBIT 3.1 IDIC: Analysis and Action the first two tasks, identify and differentiate, behind the scenes and out of the cus- tomer's sight; they constitute insight. The latter two tasks, interact and customize, are customer-facing steps that require participation on the part of the individual cus- tomer. Visible to the customer, they constitute action. You'll recall from Chapter 1 that "interacting" and "customizing" are the two capabilities an enterprise must have in order to engage customers in relationships and that the degree to which a firm uses each of these capabilities is an easy way to categorize the type of customer strategy it is pursuing-mass, niche, database, or one-to-one Learning Relation- ship. We can also think of the identify and differentiate steps as the tasks that make up "analytical customer relationship and experience management" or "customer insight," while interact and customize are the tasks involved in "operational cus- tomer relationship and experience management" or "customer experience." Throughout the rest of this book, we refer back to this set of four implementa- tion tasks as the IDIC methodology. As a model for relationship management pro- cesses, this methodology can be applied in any number of situations. For instance, it could help a company understand the steps it must take to make better use of its call center for initiating and strengthening customer relationships. Applied to a sales force, it could be used to understand the strengths and weaknesses of a new con- tact management application or to improve a sales compensation policy. We devote specific chapters in the book to examining all the activities and processes, as well as the pitfalls and problems, associated with each of these four tasks. IDIC Process: A Framework for Managing Customer Relationships and Experience 82 How Does Trust Characterize a learning Relationship? Before we begin this journey, we will spend the rest of this chapter discussing in greater detail just what it means to say that trust is a quality that will character. ize a good customer relationship. In an enterprise focused on customer-specific activities, any single customer's purchase transactions will take place within the context of that customer's previous transactions as well as future ones. The buyer and seller collaborate with the buyer interacting to specify the product, and the seller responding with some change in behavior appropriate for that buyer. In other words, the buyer and seller , in a relationship, must be willing to trust each other far beyond the general reputation of the brand. By extension, we can easily see that the more "relationship-like" any series of purchase transactions is, the more that trust will become a central element in it. When a company is focused on building customer equity, earning customer trust becomes an inherent goal of its decision making. It's not possible to balance the creation of long- and short-term value, to build Return on Customer, or to focus resources on getting customers to share information that helps us build superior customer experiences unless the company understands that the lifetime values of customers are just as important as current sales and profits. A relationship of trust is one in which both parties feel "comfortable" continuing to interact and deal with each other, whether during a purchase, an interaction, or a service transaction. Trust rarely happens instantaneously. Even if the trusted source has been recommended by another, customer must "feel" the trust from within before he will begin to divulge personal information about himself. The Speed of Trust Stephen M. R. Covey Cofounder and CEO, Coreylink Worldwide Simply put, trust means confidence. The opposite of trust-distrustis suspi- cion. When you trust people, you have confidence in them in their integrity and in their abilities. When you distrust people, you are suspicious of them-of their integrity, their agenda, their capabilities, or their track record. It's that sim- ple. We have all had experiences that validate the difference between relation- ships that are built on trust and those that are not. These experiences clearly tell us the difference is not small; it is dramatic. Trust is a function of two things: character and competence. Character includes your integrity, your motive, your intent with people. Competence includes your capabilities, your skills, your results, your track record and both a vital Chapter 3: Customer Relationships: Bade Building Blocks of IDIC and Trust With the increasing focus on ethics in our society, the character side of trust is fast becoming the price of entry in the new global economy. However, the differentiating and often ignored side of trust-competence-is equally essential. You might think a person is sincere, even honest, but you won't trust that person fully if he or she doesn't get great results. And the opposite is true. A person might have great skills and talents and a good track record, but if he or she is not honest, you're not going to trust that person either. For example, I might trust someone's character implicitly, even enough to leave him in charge of my children when I'm out of town. But I might not trust that same person in a business situation because he doesn't have the com- petence to handle it. On the other hand, I might trust someone in a business deal whom I would never leave with my children; not necessarily because he wasn't honest or capable, but because he wasn't the kind of caring person 1 would want for my children. While it may come more naturally for us to think of trust in terms of charac- ter, it's equally important for us to think in terms of competence. Think about it: People trust people who make things happen. They give the new curriculum to their most competent instructors. They give the promising projects or sales leads to those who have delivered in the past. Recognizing the role of competence helps us identify and give language to underlying trust issues we otherwise can't put a finger on. From a line leader's perspective, the competence dimension rounds out and helps give trust its harder, more pragmatic edge. Here's another way to look at it. The increasing concern about ethics has been good for our society. Ethics (which is part of character) is foundational to trust, but by itself is insufficient. You can have ethics without trust but you can't have trust without ethics. Trust, which encompasses ethics, is the bigger idea. Excerpt from Stephen M. R. Covey and Rebecca R. Merrill, The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything (New York: Free Press, 2006), pp. 5, 30. According to Covey and Merrill, "the true transformation starts with building credibility at the personal level. The best leaders are those who have made trust an explicit objective, being aware of the quantifiable costs associated with the lack of it in a company or a relationship. One of the simplest ways to look at the quantifi- able costs of a so-called soft factor, such as trust, is to think about a simple transac- tion taking place between two parties. When the two parties in business trust each other, they can act more quickly and minimize the frictional costs of the transaction, such as spending on lawyers, contracts, or due diligence. With the increase in trust in a given relationship, not only are costs lower, but the time required to complete the transaction also goes down significantly. Covey points out that when Warren