Question: 1. What SMRT did do wrong? Recourses and how they were used (efficiency) Proactive and reactive actions 2. In times of crisis, such as the

1. What SMRT did do wrong?

- Recourses and how they were used (efficiency) Proactive and reactive actions

2. In times of crisis, such as the one faced by SMRT during the breakdown, what management strategies could be employed (e.g. avoidance)? Benefits and costs of each?

- There are many crisis strategies or crisis communication frameworks. You can use anyone you like.

3. Comment on SMRTs immediate response to the train breakdown. Was it adequate?

- List key actions taken by SMRT, describe their objectives and evaluate the results

4. In hindsight, what could SMRT have done differently?

- Use the list of actions discussed in question 3 and suggest what would you do differently

5. Address the service quality gap present during the 2015 breakdown. Which of those gaps have the post-breakdown recovery measures adequately addressed?

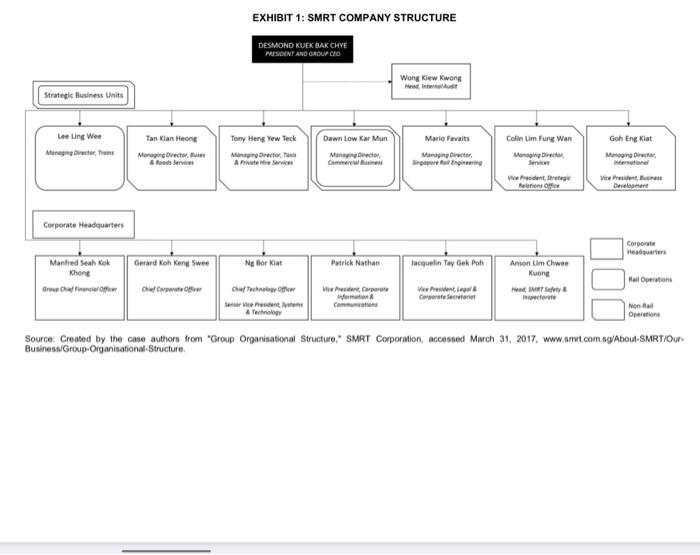

SMRT: GETTING BACK ON TRACK 1 Thompson S. H. Teo, Cherie Heng. Cheryl Lee, Zhuoran Liu, Shi Qing Ng. and Xinyi Shemy Yuan wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to ilfustrate either effective or ineffective handing of a manageriaf situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. This publication may not be transmitted, photocopiod, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission fo reproduce materials, contact tvey Publishing, ivey Business School, Westem Untversity, London, Ontario, Canada, NGG ON1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) cases Copyright 0 2018. National University of Singapore and tvey Business School Foundation Version: 20180302 On July 7, 2015, SMRT [Singapore Mass Rapid Transit] Corporation Ltd (SMRT) experienced its largest system-wide train breakdown during the evening peak hour, which affected more than 413,000 commuters. 2 Affected commuters took to social media to voice their opinions, many of which were negative and scrutinized SMRT's handling of the crisis. Singapore's then transport minister, Lui Tuck Yew, also took to Facebook to express his concern and ordered SMRT to work through the nights to search for the cause of the train breakdown." As the chief executive officer (CEO) of SMRT, Desmond Kuek Bak Chye had a tough challenge ahead. What crisis management strategies could SMRT adopt? Was SMRT's immediate response to the train breakdown adequate? What could SMRT have done differently? SMRT CORPORATION LTD Established in 1987, SMRT was one of Singapore's key multi-modal land transport providers. Its core businesses included rail operations, maintenance, and engineering as well as bus, taxi, and automotive services. It also had complementary integrated businesses in retail, media, and marketing; it owned properties; and it was in retail management." Led by Kuck, SMRT consisted of five key strategic business units, two of which were related to rail operations (see Exhibit 1). Within its corporate headquarters, the SMRT Safety and Inspectorate was responsible for driving SMRT's safety and security systems, which included assuring the quality of its trains. The Inspectorate worked closely with the business units to achieve a safe and reliable transport system and environment. SMRT listed on the Singapore Exchange in July 2000. Over the years, SMRT had received various prestigious awards that recognized its ability to deliver not only safe and reliable travel, but also innovative solutions and lifestyle convenience. In 2014, SMRT became the second metro in Asia to achieve ISO 55001 certification for an integrated, effective management system for asset management., But, beginning in 2011, SMRT began to face train disruptions and breakdowns of varying severity, which greatly inconvenienced and frustrated the public who depended heavily on SMRT's rail transportation to travel. By late 2016, SMRT had been wholly acquired by Temasek Holdings Private Limited (Temasek Holdings) and de-listed from the Singapore Stock Exchange, and had sold all its train operating assets to the Singapore government.? CEO DESMOND KUEK BAK CHYE Kuek started his tenure as CEO and president of SMRT on October 1, 2012. He was a member of the Civil Service College Board and chaired the board's audit committee. He was also a member of the international advisory panel for the Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, and a member of the advisory board at SAP Asia Pacific Japan and at the College of Engineering at Nanyang Technological University. Prior to joining SMRT, Kuek served with distinction in both the military and the civil service. From 1982 to 2010, Kuck served in the Singapore Armed Forces and held the leadership positions of chief of army in 2003 and chief of defence force in 2007. Kuck later went on to serve as permanent secretary in the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources from 2010 to 2012 . Kuek had also been a board member at various organizations, including Singapore Technologies Engineering Ltd and its subsidiaries, the Defence Science and Technology Agency, and JTC Corporation. He also served on the Housing and Development Board under the Ministry of National Development and the on the board of International Enterprise Singapore under the Ministry of Trade and Industry. 11 Kuck held a Master of Arts in engineering science from Oxford University and a Master in Public Administration from Harvard University. He had also attended the advanced management program at the International Institute for Management Development in Switzerland. 11 THE TRANSIT BREAKDOWN The breakdown of SMRT's transit system on July 7,2015, began at 7:15 p.m. when lights in the affected trains flickered, then went out completely. 12 Problems in the power system led to a system-wide disruption on two of the most heavily used mass rapid transit (MRT) lines: the North-South Line and the East-West Line. "' Train service on both lines was shut down for more than two hours, resulting in thousands of commuters spilling out of the exits of SMRT's 54 train stations during the evening rush hour. 14Only2 at 9:20 p.m. and 10:35 p.m. did train services resume on the East-West and North-South Lines, respectively. However, trains were required to run at slower speeds as a precaution. 15 Affecting more than 413,000 commuters, many of whom only managed to reach home at midnight, this train breakdown became the largest Singapore had experienced. 16 Cause of the Breakdown The breakdown was caused by trips in the electrical power switches at multiple locations in the train network. Investigations revealed that the effectiveness of one of the third-rail insulators between Tanjong Pagar and Raffles Place MRT stations was reduced, causing faults in the electrical system and tripping power switches. The insulator's effectiveness had been reduced significantly by a wet tunnel environment and buildup of conductive mineral deposits on the insulator, both of which were the result of a tunnel leak and inadequate maintenance. 17 Further investigations by the Land Transport Authority ( LTA) also revealed that SMRT had prior knowledge of the seepage of water into the tunnel but did not rectify the problem for more than a month. 18 SMRT's Immediate Response SMRT had faced a similar situation in 2011 when two major train service disruptions occurred on the NorthSouth Line on December 15 th and 17th, affecting around 127,000 commuters. However, it appeared that experience had done little to prepare SMRT for handling the massive breakdown on July 7,2015,19 In fact, SMRT failed to heed many of the recommendations for handling breakdowns made by the Committee of Inquiry in 2012 when it reviewed the breakdowns in 2011. 20 During the breakdown in July 2015, SMRT's efforts included deploying all available bus resources to supplement regular bus services, all of which were offered to commuters for no cost at about 7:20p.m. The additional buses were meant to ferry commuters caught in the massive disruption. 21 However, SMRT failed to activate bus-bridging services as recommended by the Committee of Inquiry. Experts believed that instead of deploying all available bus resources to supplement regular bus services, the extra bus resources should have been used to undertake different routes, such as taking commuters to bus interchanges where there were more bus services to choose from, or running parallel to the disrupted train routes so that the buses served as a direct alternative to the disrupted train services. 22 SMRT's sole reliance on supplementing existing bus services failed to ease congestion at many of the affected MRT stations and at the bus stops near these stations. Many of the buses were extremely crowded, and despite the supplemented bus service, the wait for buses remained long, sometimes as long as half an hour (or more than double the normal waiting time). 23 Many commuters were also confused, not knowing which bus stops to use and which buses to take to reach their desired destinations. 24 Commuters needed to approach staff one by one for clarification, adding to the congestion. SMRT's attempts to manage the breakdown by deploying 700 staff to offer assistance also achieved little success. 25 SMRT staff were deployed at Eunos MRT station to provide information and assistance to affected commuters. Commuters were also given leaflets that provided information about alternative modes of transport, such as taxis or free public buses to other stations. However, commuters claimed that the SMRT staff arrived at the scene belatedly and the information they conveyed resulted in more confusion than assistance. 26 At Raffles Place MRT station, instead of telling commuters that the trains had stopped running, staff said the train journey had been delayed. It was only much later that passengers were informed that the trains had stopped functioning completely. 27 Another source of confusion was SMRT's attempts to offer fare refunds to commuters. When the commuters discovered that the fare refunds were not automatic, and information was not provided about a deadline to seek a refund, many who were affected by the massive breakdown formed long queues at MRT stations to get their refund. This only contributed to the human congestion and added to the overall confusion. 28 The Public's Response Many commuters who experienced the breakdown were outraged, not only by the scale of the breakdown, but also by how it was handled. Muslim commuters were further compromised because many of them were heading home to break their Ramadan fast when the breakdown occurred. 29 SMRT's failure to provide clear and timely information and instructions to the public, as well as its failure to ease the inconvenience faced by commuters, left many extremely dissatisfied and apprehensive in already disordered circumstances. Social media teemed with comments and posts displaying outright frustration with SMRT's poor handling of the breakdown (see Exhibit 2). 30 Previous breakdowns, which had led to limited improvements, added to commuters' frustration. As expected, the comments and posts on various social media platforms, including SMRT's own Facebook page, ranged from recommendations of possible solutions to pure sarcasm. 31 The Government's Response During the breakdown, officers from the police and the Singapore Civil Defence Force were deployed to help with crowd control, for example, by holding a rope at bus stops to regulate boarding. This quick action was attributed to a whole-of-government approach established by the Ministry of Home Affairs to ensure commuter safety in the public transport system. 32 The transport minister, Lui, apologized for the breakdown and assured the public that he was "extremely concemed" about the incident. Lui said, "This is the first time that services on both the North-South and East-West Lines were affected at the same time. I am sorry that so many commuters experienced massive disruptions to their joumeys during the evening peak hours. *3] The chief executive of LTA, Chew Men Leong, disclosed that it had assembled and activated all the assets it had, including buses from the public operator, SBS Transit Limited, to help on the night of the breakdown. LTA had also considered hiring private buses if necessary. 34 Leong said, "We will have to have a deep examination [of] what worked, what didn't work. We pull back and ask ourselves what are the additional contingency actions and plans we need to put together so we can be better prepared. nes In a media statement to the public, LTA confirmed it would conduct a full investigation into the breakdown. 36 It appointed a team of five experts from Parsons Brinkerhoff and Meidensha Corporation to determine the root cause of the power trips and propose recommendations for improvements. 37 SMRT's Subsequent Response The morning after the breakdown, SMRT held a press briefing, during which both Kuck and Leong apologized to the public. SMRT's managing director of trains, Lee Ling Wee, also explained the series of events that occurred prior to the breakdown. is He clarified that SMRT made the decision to stop the service and de-train passengers in the interests of passenger safety. 39 Kuck also defended SMRT against arguments that it should have identified the problem before it affected the system on such a large scale. Kuek said, "We can shorten our mean time between failures, we can step up our maintenance regime and intensify the amount of maintenance checks that we do on a regular basis, but it will still not be able to 100 per cent catch every one of the potential faults that can take place, especially when the system is at the age that it is. 40 SMRT later shared in an official statement to the public that it would be increasing its focus on maintenance. The company committed to increasing its expenditure on network maintenance-related issues to 50 per cent of its total rail revenue in 2015 - an increase from the then investment rate of 41 per cent. This included expenditure on expanding the fleet and strengthening SMRT's ageing rail network." Penalties After detailed investigations, LTA concluded that the breakdown was due to maintenance lapses by SMRT. Given the severity of the breakdown, the authority imposed a fine of SGDS5.4 million 42 on SMRT under section 19 of the Ropid Transit Systems Act. . The fine was the largest imposed on a rail operator; all of it would be channelled to the Public Transport Fund, which paid for transport vouchers to help needy families. In addition to the fine, LTA also required that SMRT provide a detailed response and a program to rectify the authority's findings. LTA also decided to conduct more frequent audits of SMRT's maintenance regimes. POST-INCIDENT RECOVERY In light of the breakdown, SMRT embarked on a series of actions to improve its reliability and public image. These strategies aimed to win back the public's trust and confidence in SMRT's service and to deliver a higher quality commuting experience. Maintenance Focus SMRT adopted a proactive and preventative approach by hiring more staff to focus on maintenance and assess problems with the tracks during the night while the service was down. SMRT adjusted the train schedule from November 2015 to the end of the year to ensure there were approximately four hours available for maintenance every night. 46 SMRT had also invested in various technologies to enhance operations and maintenance. For example, sensors helped to collect real-time data from train operations, and an Asset Information Management System with embedded artificial intelligence capabilities helped to highlight assets due for replacement. 47 Maintenance work to replace aging wooden track sleepers with longer-lasting concrete ones had been ongoing, and SMRT completed the track sleeper replacement work on the North-South Line in April 2015 and the East-West line in December 2016. .. The sleeper replacement program was only one of the projects under SMRT's Multi-Year Rail Renewal Program. 49 The other projects involved renewing and upgrading the North-South and East-West Lines, which included replacing the signals and the third rail. The signalling work, which would be completed by 2018 , aimed to reduce the headway between trains from 120 seconds to 100 seconds, cutting the waiting time for passengers and easing congestion during peak hours. Replacing the third rails would increase the reliability of the trains by reducing the chances of power faults caused by worn third rails. That project was to be completed by 2017. . Another prominent improvement SMRT made in response to the 2015 incident was to open a $5 million maintenance operations centre. 52 The main function of this hub was to facilitate better coordination among SMRT's teams and cngineers. Kuck said this centre would allow the staff to rely on "a network capability to provide system support to all the different nodes" when they performed maintenance, carried out repairs, and responded to incidents. 53 Employee Training Kuek released an official statement a week after the incident to share SMRT's innovation and transformation plans. Among its plans was a focus on developing the technical competency of SMRT's core employees so they were well equipped to manage increasingly complex functions. Thus, SMRT launched a "comprehensive training competency and career development scheme for their engineers and technicians,, p4 and it collaborated with academic and research institutes to hire new talent. Employees were also trained in public drills such as "Operations Greyhound," which involved simulating a train breakdown to make employees operationally ready. Communication A main source of dissatisfaction among commuters was SMRT's failure to provide notice and guidance during the train breakdowns, and its lack of transparency and accountability after the breakdowns. 35 As a result, SMRT planned to improve its communication with commuters by using various channels. In 2015 , SMRT embarked on a marketing campaign titled "We're working on it." The campaign portrayed the hard work of SMRT's staff, including engineers who worked late at night to conduct train maintenance services, and crowd control staff. Posters communicated the employees' stories and work goals to the public. SMRT posted status updates on its Twitter feed and Facebook page to inform commuters about train delays, and it updated its blog 56 to increase accountability. SMRT also provided SMS text alerts to service subseribers, and installed boards at various stations that could be used to inform travellers about delays and available bus services. Crowd Control during Crisis Collaboration was also one of SMRT's key strategies. In 2013. SMRT had established collaboration plans with LTA, the police, and the Singapore Civil Defence Force, which would be activated to manage crowds during train breakdowns. SMRT extended its collaboration to establish partnerships with other transport providers to facilitate a better crisis-management transport system, and it expanded its crowd control team to deal with emergency breakdowns. As of 2016, free bus services would be provided during train disruptions. 57 In addition to bridging train service with buses, SMRT would activate special shuttle buses at major interchanges. These shuttle buses would operate on four routes, in a loop: Jurong East-Choa Chu Kang, Buona Vista-Boon Lay, Bishan-Woodlands, and Paya Lebar-Tampines. Refund Policies SMRT improved its refund system to reduce the amount of time commuters would have to spend queucing for a refund at the passenger service centres. With clearer protocols for processing refunds 64 and distributing complimentary trip vouchers, SMRT achieved a fair and efficient system for managing customer relations during breakdowns. After the breakdown in July 2015, SMRT also installed beacons at bus stops at the MRT stations." These beacon lights would be activated during a train breakdown to inform bus drivers that there had been a breakdown and that bus fares were to be waived. Comparison with Hong Kong MTR Public dissonance ensued after a report compared the investments in train maintenance made by Hong Kong's MTR Corporation (HK MTRC) with those made by SMRT. The report indicated that HK MTRC spent 37 per cent of its rail revenue on maintenance, renewal, and improvements in its train service, but SMRT dedicated only 19 per cent of its rail revenue for the same cause. However, Kuek publicly denounced the credibility of the article and argued that SMRT's investments into other maintenance-related activities had not been considered. Nonetheless, SMRT released a public statement announcing that it was increasing its maintenance-related expenses for the train network. In response to public outrage, SMRT decided to benchmark itself against HK MTRC in pursuit of a bestin-class metro system. 60 The annual meeting of the Community of Metros, a confidential forum for metros to learn from one another, was one of the channels SMRT used to exchange information with HK MTRC and other reputable metros around the world. SMRT believed that sharing lessons and experiences provided it with clearer directions for improving services and reliability. 61 In addition, SMRT was looking at using drones with HK MTRC for surveillance, crowd management, and asset maintenance. 62 THE NEW RAIL FINANCING FRAMEWORK AND PRIVATIZING SMRT Following the spate of train disruptions and public outrage, the Ministry of Transport announced on July 15, 2016, that LTA would take over all of SMRT's rail operating assets for $1.06 billion as part of a new model of rail operations known as the New Rail Financing Framework (NRFF). In return, SMRT would pay an annual licence fee to LTA, with the fee based on SMRT's profitability. Under the new framework, SMRT would transfer all of its capital expenditure obligations to LTA, resulting in improved cash flows for SMRT. Additionally, SMRT's transformation into an asset-light company would unlock more resources for improving its customer services. The NRFF proposal was approved by SMRT shareholders, with 98.8 per cent of the votes. On July 20, 2016, Singapore's state-owned investment fund, Temasek Holdings, announced an acquisition offer of \$1.68 for each SMRT share in an attempt to de-list SMRT from the Singapore Stock Exchange and privatize the company as a wholly owned subsidiary of Temasek Holdings. At the time of the announcement, Temasek Holdings was already SMRT's largest shareholder with 54 per cent of its shares. In response to the privatization announcement, SMRT Chairman Koh Yong Guan explained that taking the company private would "allow SMRT to better fulfil its role as a public transport operator without the pressure of short-term market expectations [and] ... also allow SMRT to be better supported as it retools and reinforces its core skillsets in engineering and maintenance,. 3. Many analysts supported the privatization, such as strategist Nicholas Teo from KGl Fraser Securities Pte. Ltd., who noted, "The notion of de-listing and privatising allows them [SMRT] to have full control of running the business without having to answer to minority shareholders, the hassle of filing quarterly reports, meeting the various auditing and regulatory requirements. " 664 The privatization offer was approved by SMRT shareholders, with 84.8 per cent of the vote. .s Many changes were in place. Would SMRT's new service recovery measures address service gaps? How would the NRFF plan and privatizing SMRT help it become a service-oriented company? Could SMRT gain back commuters' trust? Source: Created by the case authors from "Group Organisational Structure." SMRT Corporation, accessed March 31, 2017, www.smvicom.sg/About-SMRTIOurBusineswGroup-Organisational-Structure