Question: 1. Why is shadow banking so popular? 2. How would you define backstop? What is shadow banking? Stijn Claessens, Lev Ratnovski 23 August 2013 There

1. Why is shadow banking so popular?

2. How would you define backstop?

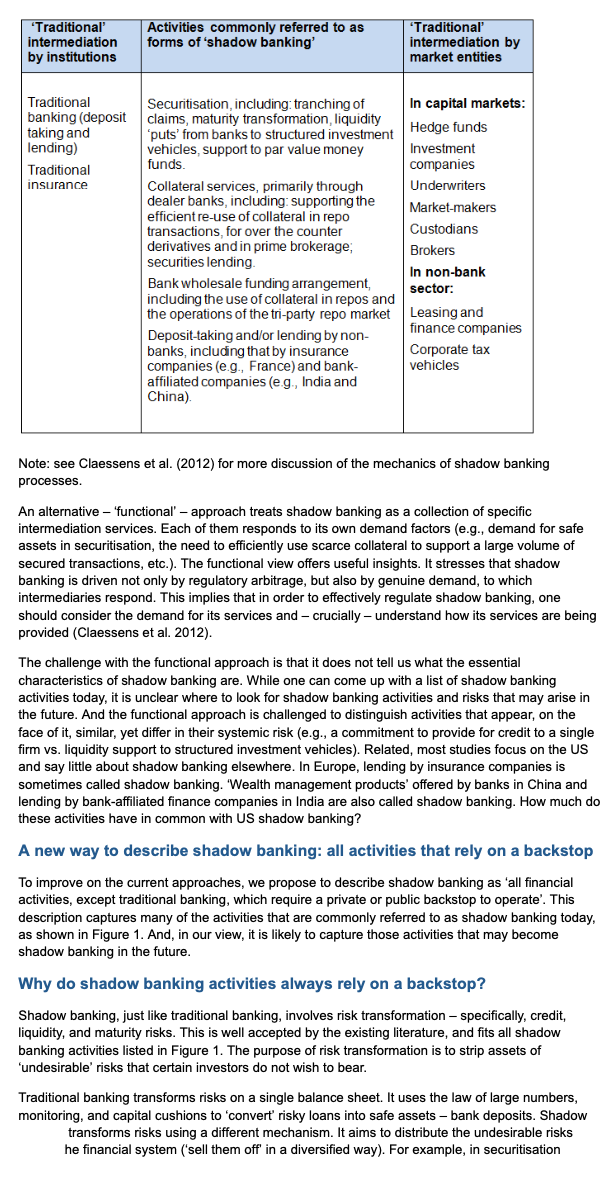

What is shadow banking? Stijn Claessens, Lev Ratnovski 23 August 2013 There is much confusion about what shadow banking is and why it might create systemic risks. This column presents shadow banking as 'all financial activities, except traditional banking, which rely on a private or public backstop to operate'. The idea that shadow banking is something that needs a backstop changes how we think about regulation. Although it won't be easy, regulation is possible. 40 A A Related There is much confusion about what shadow banking is. Some equate it with securitisation, others with non- The roots of shadow banking Enrico Perotti traditional bank activities, and yet others with non- bank lending. Regardless, most think of shadow banking as activities that can create systemic risk. This column proposes to describe shadow banking as 'all financial activities, except traditional banking, which rely on a private or public backstop to operate'. Backstops can come in the form of franchise value of a bank or insurance company, or a government guarantee. The need for a backstop is a crucial feature of shadow banking, which distinguishes it from the usual" intermediated capital market activities, such as custodians, hedge funds, leasing companies, etc. It has been very hard to 'define' shadow banking The Financial Stability Board (2012) describes shadow banking as "credit intermediation involving entities and activities (fully or partially) outside the regular banking system. This is a useful benchmark, but has two weaknesses: . First, it may cover entities that are not commonly thought of as shadow banking, such as leasing and finance companies, credit-oriented hedge funds, corporate tax vehicles, etc. (Figure 1). Second, it describes shadow banking activities as operating primarily outside banks. But in practice, many shadow banking activities, for instance, liquidity puts to securitisation structured investment vehicles, collateral operations of dealer banks, repos, and so on, operate within banks, especially systemic ones (Pozsar and Singh 2011, Cetorelli and Peristiani 2012). Both reasons make the description less insightful and less useful from an operational point of view. Figure 1. Spectrum of financial activities 'Traditional intermediation by institutions Activities commonly referred to as forms of 'shadow banking' 'Traditional intermediation by market entities In capital markets: Traditional banking (deposit taking and lending) Securitisation, including: tranching of claims, maturity transformation, liquidity 'puts' from banks to structured investment vehicles, support to par value money funds. Hedge funds Investment companies Traditional insurance Underwriters Market-makers Custodians Brokers Collateral services, primarily through dealer banks, including supporting the efficient re-use of collateral in repo transactions, for over the counter derivatives and in prime brokerage, securities lending Bank wholesale funding arrangement, including the use of collateral in repos and the operations of the tri-party repo market Deposit-taking and/or lending by non- banks, including that by insurance companies (e.g., France) and bank- affiliated companies (eg., India and China) In non-bank sector: Leasing and finance companies Corporate tax vehicles Note: see Claessens et al. (2012) for more discussion of the mechanics of shadow banking processes. An alternative - 'functional' - approach treats shadow banking as a collection of specific intermediation services. Each of them responds to its own demand factors (e.g., demand for safe assets in securitisation, the need to efficiently use scarce collateral to support a large volume of secured transactions, etc.). The functional view offers useful insights. It stresses that shadow banking is driven not only by regulatory arbitrage, but also by genuine demand, to which intermediaries respond. This implies that i order to effectively regulate shadow banking, one should consider the demand for its services and crucially - understand how its services are being provided (Claessens et al. 2012). The challenge with the functional approach is that it does not tell us what the essential characteristics of shadow banking are. While one can come up with a list of shadow banking activities today, it is unclear where to look for shadow banking activities and risks that may arise in the future. And the functional approach is challenged to distinguish activities that appear, on the face of it, similar, yet differ in their systemic risk (e.g., a commitment to provide for credit to a single firm vs. liquidity support to structured investment vehicles). Related, most studies focus on the US and say little about shadow banking elsewhere. In Europe, lending by insurance companies is sometimes called shadow banking. ' Wealth management products' offered by banks in China and lending by bank-affiliated finance companies in India are also called shadow banking. How much do these activities have in common with US shadow banking? A new way to describe shadow banking: all activities that rely on a backstop To improve on the current approaches, we propose to describe shadow banking as 'all financial activities, except traditional banking, which require a private or public backstop to operate'. This description captures many of the activities that are commonly referred to as shadow banking today, as shown in Figure 1. And, in our view, it is likely to capture those activities that may become shadow banking in the future. Why do shadow banking activities always rely on a backstop? Shadow banking, just like traditional banking, involves risk transformation - specifically, credit, liquidity, and maturity risks. This is well accepted by the existing literature, and fits all shadow banking activities listed in Figure 1. The purpose of risk transformation is to strip assets of 'undesirable' risks that certain investors do not wish to bear. Traditional banking transforms risks on a single balance sheet. It uses the law of large numbers, monitoring, and capital cushions to convert' risky loans into safe assets - bank deposits. Shadow transforms risks using a different mechanism. It aims to distribute the undesirable risks he financial system ('sell them off' in a diversified way). For example, in securitisation shadow banking strips assets of credit and liquidity risks through tranching and providing liquidity puts (Pozsar et al. 2010, Pozsar 2011, Gennaioli et al. 2012). Or it facilitates the use of collateral to reduce counterparty exposures in repo markets and for over the counter derivatives (Gorton 2012, Acharya and nc 2013). 1 While shadow banking uses many capital markets type tools, it differs also from traditional capital markets activities - such as trading stocks and bonds - in that needs a backstop. This is because, while most undesirable risks can be distributed away, some residual risks, often rare and systemic ones ("tail risks"), can remain. Examples of such residual risks include systemic liquidity risk in securitisation, risks associated with large borrowers' bankruptcy in repos and securities lending, and the systematic component of credit risk in non-bank lending (e.g., for leveraged buyouts). Shadow banking needs to show it can absorb these risks to minimise the potential exposure of the ultimate claimholders who do not wish to bear them. Yet shadow banking cannot generate the needed ultimate risk absorption capacity internally. The reason is that shadow-banking activities have margins that are too low. To be able to easily distribute risks across the financial system, shadow banking focuses on 'hard information' risks that are easy to measure, price and communicate, e.g., through credit scores. This means these services are contestable, with too low margins to generate sufficient internal capital to buffer residual risks. Therefore, shadow banking needs access to a backstop, i.e., a risk absorption capacity external to the shadow banking activity. The backstop for shadow banking needs to be sufficiently deep. First, shadow banking usually operates on large scale, to offset significant start-up costs, e.g., of the development of infrastructure. Second, residual, 'tail' risks in shadow banking are often systemic, so can realise en masse. There are two ways to obtain such a backstop. One is private - by using the franchise value of existing financial institutions. This explains why many shadow banking activities operate within large banks or transfers risks to them (as with liquidity puts in securitisation). Another is public - by using explicit or implicit government guarantees. Examples include, besides the general too-big-to-fail implicit guarantee provided to the large banks active in shadow banking, the Federal Reserve securities lending facility that backstops the collateral intermediation processes, the implicit too-big- to-fail guarantees for tri-party repo clearing banks and other dealer banks (Singh 2012), the bankruptcy stay exemptions for repos which in effect guarantee the exposure of lenders (Perotti 2012), or implicit guarantees on bank-affiliated products (as widely described in the press regarding so called 'wealth management products' in China (see The Economist 2013, Bloomberg 2013a, 2013b)) or on liabilities of non-bank finance companies (as noted for India, see Acharya et al. 2013). The need for a backstop as a 'litmus test' for shadow banking Assessing whether an activity relies on a backstop to operate could be used as the key test of whether it represents shadow banking. For example, the 'usual' capital market activities in the right column of Figure 1) do not need external risk absorption capacity (because some, like custodian or market-making services, involve no risk transformation, while others, like hedge funds, have high margins), and so are not shadow banking. Only activities that need a backstop - because they combine risk transformation, low margins and high scale with residual tail' risks - are systemically- important shadow banking. Policy implications Acknowledging the need for a backstop as a critical feature of shadow banking offers useful policy implications: First, it gives direction on where to look for new shadow banking risks: among financial activities that need franchise value or government guarantees to operate. Non-traditional activities of banks or insurance companies are 'prime suspects'. It is hard to point to the shadow banking-like activities which may give rise to future systemic risks conclusively, but one example could be the liquidity services provided by sponsor banks to exchange traded funds, or large-scale commercial bank backstops for leveraged buyouts. . Second, it explains why shadow banking poses significant macro-prudential and other regulatory challenges. Shadow banking uses backstops to operate. But this does not mean that all shadow banking 3 should have such a backstop. Backstops reduce market discipline and thus can enable banking to accumulate (systemic) risks on a large scale. In the absence of market e, the one force which can prevent shadow banking from accumulating risks is regulation. Third, it suggests that shadow banking is almost always within regulatory reach, directly or indirectly. Regulators can control shadow banking by affecting the ability of regulated entities to use their franchise value to support shadow banking activities (as was done in the aftermath of the crisis by limiting the ability of banks to offer liquidity support to structured investment vehicles). Or by managing the implicit) government guarantees (as is attempted in the US Dodd-Frank Act by limiting the ability to extend the safety net to non-bank activities and entities; or by general attempts underway to reduce the too-big-to-fail problem). Put differently, regulators can try to reduce those forms of shadow banking activities that are undesirable by taking away their backstop. Finally, it suggests that the migration of risks from the regulated sector to shadow banking - often suggested as a possible unintended consequence of tighter bank regulation is a lesser problem than some fear. Shadow banking activities cannot migrate on a large scale to areas of the financial system that do not have access to franchise values or government guarantees. This by itself does not make spotting the activity occurring within the reach of the regulator necessarily easier, but at least it narrows the task Editor's note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent those of the IMF

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts