Question: 3. Beyond relocating resources, what other changes will you need to make in the Trauma Unit, and in the hospital in general, to ensure the

3. Beyond relocating resources, what other changes will you need to make in the Trauma Unit, and in the hospital in general, to ensure the new unit will function better than the previous arrangement?

4. If you were to implement a major organizational change, such as the co-location of resources dedicated to trauma, what challenges might you face? Consider operational, clinical, social (workforce), and economic challenges for hospital management.

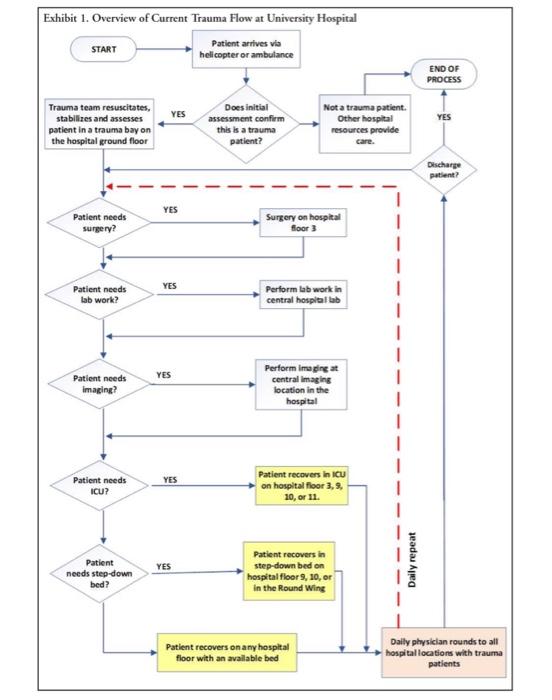

AT UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL Susan Bates, the newly appointed CEO of University Hospital, ' was concerned about the hospital's financial performance in trauma care delivery. Trauma patients were patients with multiple injuries who required emergency care involving rapid resuscitation. "These individuals rypically were victims of vehicle crashes, shootings, stabbings, or injuries at work or home-often incurred under the influence of drugs or alcohol. University Hospital, as a Level I Trauma Center, provided the most comprehensive trauma care of its kind within a 65,000 square-mile area. (See Appendix A for definitions of trauma care levels and Appendix B for criteria triggering Level I trauma alerts.) In spite of the importance of caring for victims of serious injuries, trauma care was a moncy-losing proposition for the hospital. Consequently, its executives questioned the continued viability of offering comprehensive, Level I trauma care services. However, they also recognized the unit's importance to the hospitals service mission and. as a teaching hospital, to its educational mission. In addition, trauma care was important to insurers who paid for the care. In selecting hospital systems to include in their networks, large health care insurers gave preference to those providing a full range of services, including trauma care. At University Hospital, a group of disconnected physicians, nurses, therapists, support staff members, accompanying equipment, and systems served the needs of about 1,200 trauma paticnts annually. With an average length of stay (LOS) of 6.2 days, there were about 20 trauma patients in the hospital on any given day, although this number could fluctuate substantially. Well aware of the dire financial siruation, David Crawley, chief trauma surgeon and director of University Hospital's trauma operations, began investigating new options for the delivery of trauma care. Although trauma patients arrived at the hospital with different injury types, they shared several care processing requirements, thus offering the potential for clustering resources around patient needs. The question before hospital administrators was whether changes to the organizational structure and process design, accompanied by changes in support services infrastructure, could make a difference. In particular, they were considering the idea of a "process-complete" arrangement in which all resources needed for trauma care would be clustered together as a separate business unit within the hospital's nearly 10 million square fect (929,000 square meters) of space. Trauma Care at University Hospital Over the past 15 years, University Hospital had delivered trauma care in a fashion characteristic of other large hospitals in the U.S., Although the process could be slightly different for each patient, the general flow was as follows (sec Exhibit 1): The term University Hospital is used throughout the case to describe a real hospital in the United States. Names of individuals and figures in the case have been disguised or modified. 2 To resuscitate means to bring someone who is unconscious, not breathing, or close to death back to a conscious or active state. 'Common characteristics across hospital trauma units in the U.S. included: (1) separate trauma bays in ER, (2) ICUs shared with other specialries, such as surgery, (3) trauma patients coming out of 1CU dispersed to units where trauma and nontrauma parients were mixed, and (4) trauma patients cared for by different nurses at different stages, none specializing in trauma (except in the ER and ICU). (This description is based on telephone interviews with two senior physicians serving on the American College of Surgeons' Committee on Trauma that certifies trauma centers nationwide.) and Karen A. Browm (Thunderbind) for the purpose of classoom discusion only and not to indicate either effective ar ineffoctire 1. A severely injured patient would arrive at the hospital from the injury location or from another hospital via ambulance or helicopter. About 40% of patients arrived by helicopter and the remainder via ambulance. Patients transporred by ambulance arrived at the emergency room (ER) on the ground floot. Patients transported by helicopter arrived on the helipad located on the roof of the hospital, and were transported from the 11th floor to the ER on the ground floor via a dedicated clevatot. 2. Based on information provided by the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) personnel or referring hospital (typically transmitted in advance of patient arrival), a patient would be assigned to a trauma bay ot, if less severcly injured, an emergency room bay, both of which were located on the ground floot. Patients routed to an emergency room bay would be the responsibility of the ER staff. Depending on the diagnosis, they would be treated and released, or treated and admitted to the hospital for further care and ultimately discharged. 3. For patients sent to the trauma bay (i.e., trauma patients), members of the trauma team provided rapid resuscitation if needed, stabilized, and then mote thoroughly assessed the patient to determine the appropriate next steps of care. 4. Trauma patients requiring surgery were transported to operating rooms (ORs) on the third floor of the hospital. 5. Trauma patients whose surgeries were complete, as well as nonsurgical trauma patients requiring close monitoring, were transported to one of five intensive care units (ICUs) located on hospital floors 3. 9, 10 . and 11. 6. Trauma patients requiring less-intensive monitoring, or those no longer needing intensive care after a stay in the ICU, were transported to step-down care beds on floors 9 or 10 in the main hospital. Some step-down patients were also placed in the round wing of the hospital. The round wing was remote from the emergency area, the ICUs, and other step-down beds, but capacity constraints sometimes made it necessary to place trauma patients there. 7. Trauma physicians visited trauma patients in all hospital locations daily to assess patient progress and direct treatment. Trauma physicians interfaced with nurses in the various locations around the hospital where trauma patients occupied beds, and with other care providers (e.g.s social workers, case managers) involved with trauma patients. 8. In the course of daily rounds, physicians prescribed, as needed, lab work, diagnostic imaging (e.g. CT scans, MRIs, and others), drugs, and surgeries for each trauma parient. Some diagnostic procedurcs and all surgeries required transport to centralized locations in the hospital where these services were provided. Lab work involved sending patient blood, urine, tissue, and other specimens to the hospital's centralized laboratory. 9. Once sufficiently recovered, a trauma patient would move to a regular bed on almost any of the hospital's floors. Trauma physicians continued their rounds to these locations. 10. Eventually, trauma patients would be discharged to one of several locations (e.g., long-term care facility, rehabilitation hospital, skilled nursing facility, patient's home, etc.). depending on the type and extent of rehabilitation necessary to continue to address the patient's injuries. According to hospital policies, trauma parients were to be assigned to an ICU or hospital floor based on the nature of their injurier. In reality, a trauma patient could be allocated to any available ICU bed and, after leaving the ICU, to any of the hospital's nearly 600 beds, wherever it happened to be available. As a resulk, trauma physicians had to spend much non-value-added time moving around the hospital to supervise care for these patients. The spatial dispersion of trauma patients also had other implications. The hospital's nurses, and especially those who staffed intensive care and step-down unirs, were caring for trauma patients along with other patients assigned to their units. Although some elements of care were common across all patients, trauma nursing relied heavily on certain skill sets (e.g. wound care, respiratory monitoring, ventilator management, IV therapy, pain management, and more). A nurse who was a generalist might see trauma patients infrequently, so there were limited opportunities to develop deep knowledge or learn from repetition. In addition, trauma patients frequently brought with them issues related to dysfunctional families and associates who elevated the hospital's need to provide security and required nursing staff members to possess special interpersonal skills. Within general guidelines for prescribing appropriate care, individual trauma physicians had their own unique procedural preferences. For nurses, these variations in work instructions meant following a variety of care routines, even for patients with similar conditions. In addition, a written doctor's order (a primary vehicle for physician-nurse communication) could not account for every clinical possibility, so an unforeseen development would require the nurse to contact the physician directly for instructions. This was frustrating for nurses and could lengthen the time between an incident and the directed intervention. Conversely, from the trauma physicians' perspective, interacting with nurses from different units added complexity. Trauma patients often needed multiple diagnostic tests and surgical procedures, each of which would require transport to a centralized imaging location or an operating room somewhere in the hospital. Patient transport carried with it a certain risk: a movable hospital bed lacked some life support and monitoring equipment, and doctors and nurses might not be available when needed. Moreover, even when precautions were carefully followed, transporting a critically ill patient through corridors, turns, elevators, and doorways in a busy hospital always presented some risk of potential injury. Access to shared hospital services was another challenge for trauma care delivery. For example, because available operating rooms were generally in short supply, trauma patients needing surgery-even if they were routinely given highest priority-invariably incurred some waiting time. There also were delays associated with radiology, which was a centralized unit serving all hospital departments. Not only did the patient have to be moved to the radiology department, but the equipment was often backed up with pre-scheduled commitments and emergencies from other departments. Care could also be delayed while clinicians waited for the results of centralized laboratory tests (e.g. blood work). A final consequence of the work arrangement at University Hospital was that trauma patients often occupied ICU beds longer than warranted by their injuries, which not only added unnecessary cost but also prevented access and increased wait times for other patients in need of these services. This happened because there were no guidelines to help clinicians decide when patients were ready to move to less-costly levels of care, and the patient flow paths were not visible or obvious in such a physically dispersed operation. Further, conflicting incentives played a contributing role. The hospital's interest was in moving patients to the lowest-cost, appropriate level of care. Physicians, who billed patients separately and were compensated for procedures, did not focus as much on patient flow, and sometimes favored the consistency associated with kecping a patient in the same place. In addition, the beds occupied by trauma patients-while being managed by trauma physicians-were housed in units with which these physicians were not formally affiliated. This further distanced the trauma physicians from an awareness of bed turnover or unit efficiency. Dr. Crawley wondered whether this was the right time to persuade CEO Susan Bates to move forward with the idea of creating a physically and organizationally integrated Level I trauma unit. Exhibit 1. Overview of Current Trauma Flow at University Hospital