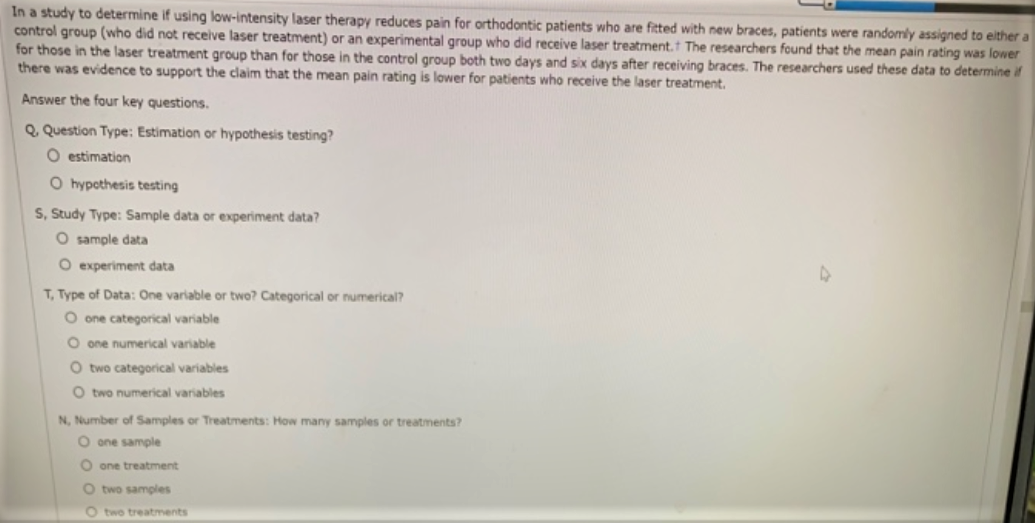

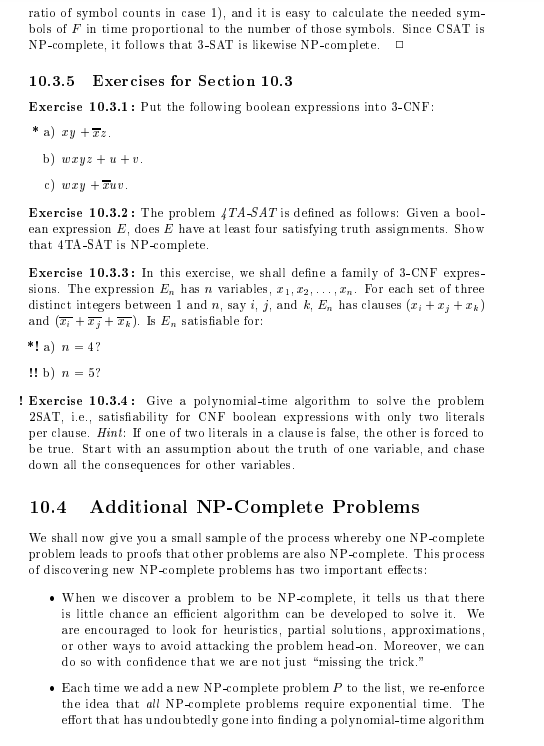

Question: 3. [NP-Complete Satisflability Problems: 3SAT][30; 5+5+10+10] To solve this problem, you should review the materials from the textbook, Section 10.3.3 NP-Completeness ofCSAT and 10.3.4 NP

![3. [NP-Complete Satisflability Problems: 3SAT][30; 5+5+10+10] To solve this problem, you](https://s3.amazonaws.com/si.experts.images/answers/2024/06/6668f5cd0a316_7006668f5cce39fd.jpg)

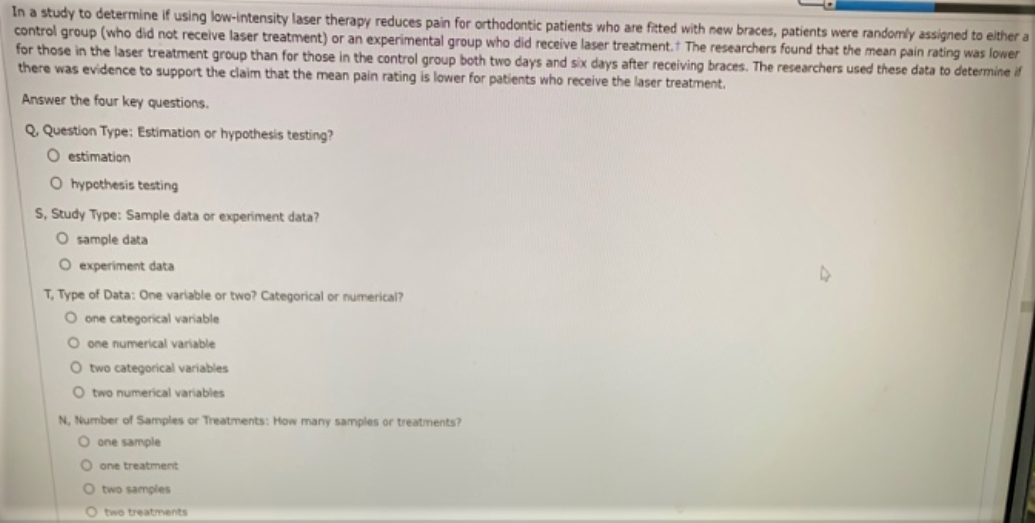

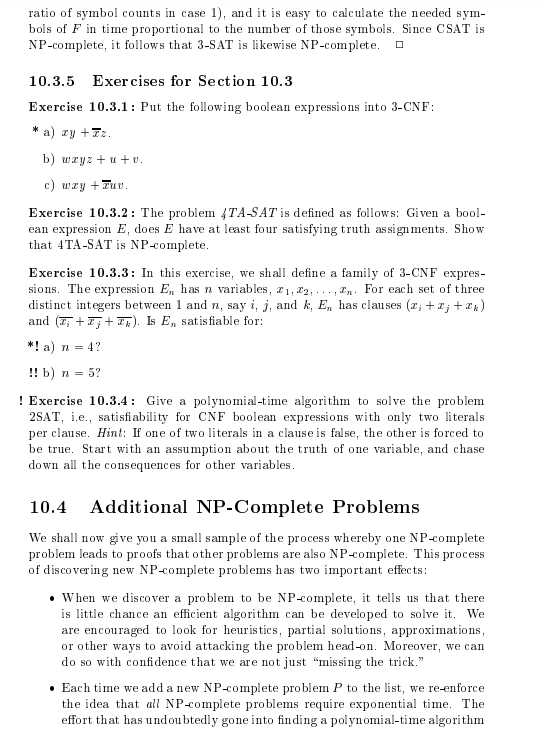

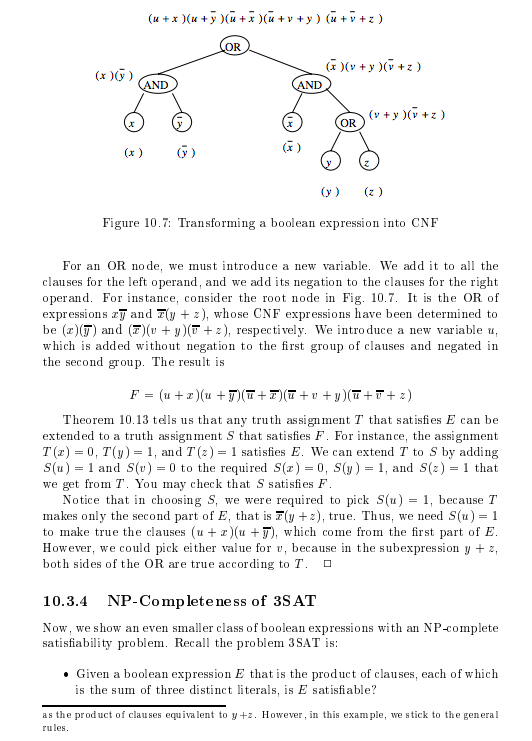

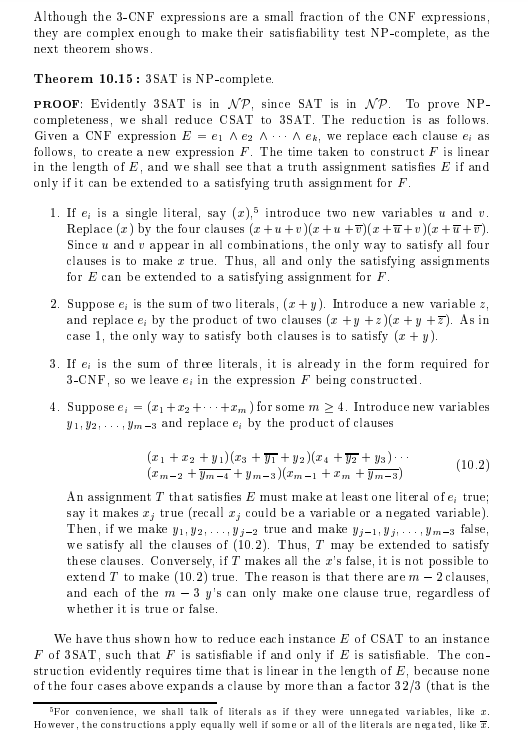

3. [NP-Complete Satisflability Problems: 3SAT][30; 5+5+10+10] To solve this problem, you should review the materials from the textbook, Section 10.3.3 "NP-Completeness ofCSAT" and 10.3.4 "NP Completeness of 3SAT", pages 452 ?458. In particular, 3SAT problem is important, for the following reason: "Cook's theorem showed the very first NP-complete problem ? whether a Boolean expression is "satisfiability" ? by reducing all problems in NP to the SAT problem in polynomial time. In addition, the problem remains NP-complete even if the expression is restricted to a product of clauses, each of which consists of ONLY THREE LITERALS ?the problem 3SAT." Consider the following Boolean expression: E = xy + Xz. Using E (as an instance), demonstrate your understanding of "3SAT is NP-complete", which is formally proved in "Theorem 10.15" in the textbook. Specifically, solve the following problems: a. Find 3-CNF for E (i.e., k=3, 3 literals) b. To prove "3SAT is NP-complete", two things must be done. First, you must showthat "3SAT is in NP." Show this is true.

![3. [NP-Complete Satisfiability Problems: 3SAT][30; 5+5+10+10] To solve this problem, you should](https://s3.amazonaws.com/si.experts.images/answers/2024/06/6668f5d26a1a7_7066668f5d2574e2.jpg)

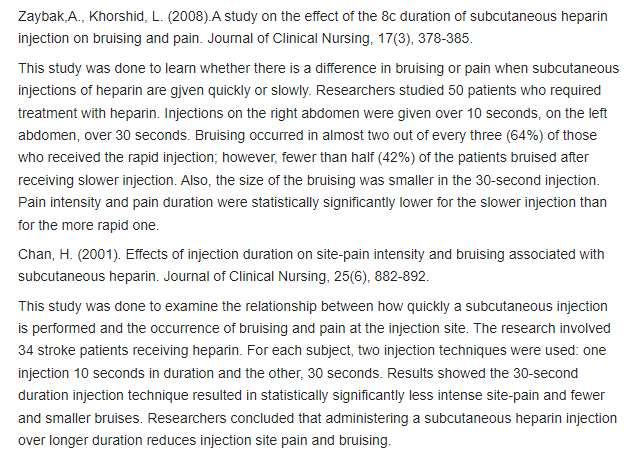

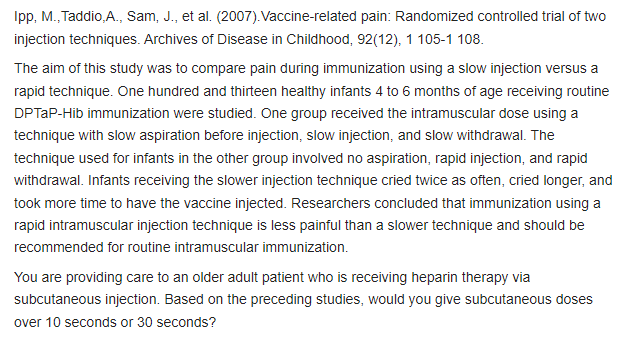

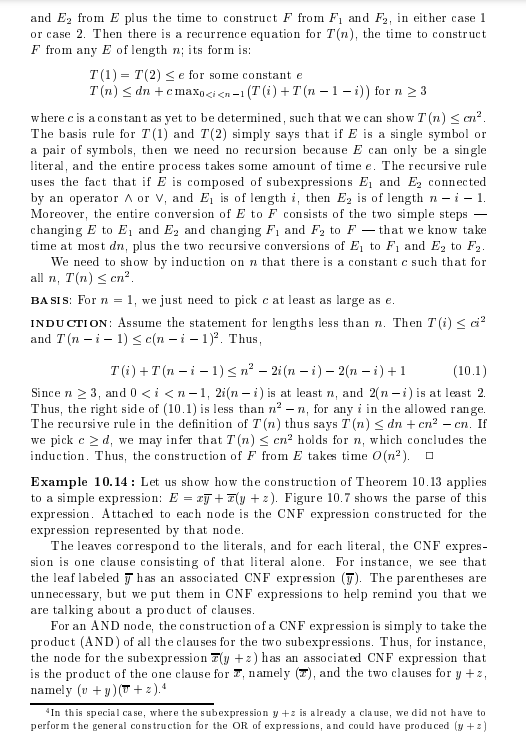

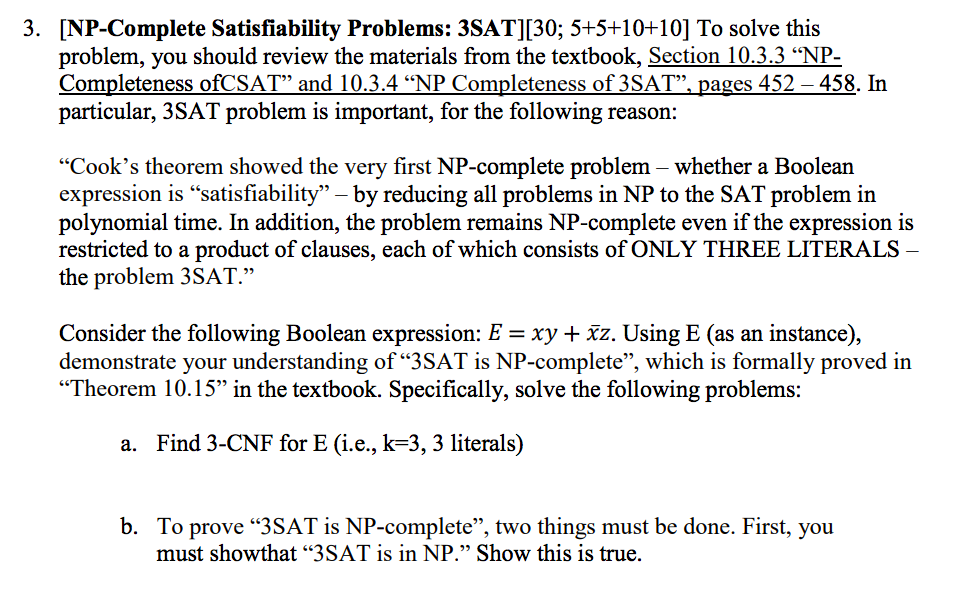

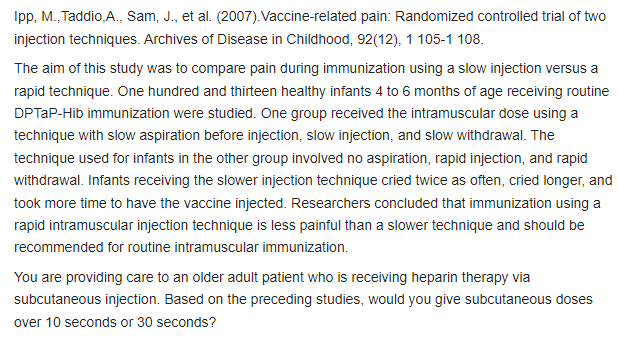

3. [NP-Complete Satisfiability Problems: 3SAT][30; 5+5+10+10] To solve this problem, you should review the materials from the textbook, Section 10.3.3 "NP- Completeness ofCSAT" and 10.3.4 "NP Completeness of 3SAT", pages 452 - 458. In particular, 3SAT problem is important, for the following reason: "Cook's theorem showed the very first NP-complete problem - whether a Boolean expression is "satisfiability" - by reducing all problems in NP to the SAT problem in polynomial time. In addition, the problem remains NP-complete even if the expression is restricted to a product of clauses, each of which consists of ONLY THREE LITERALS - the problem 3SAT." Consider the following Boolean expression: E = xy + xz. Using E (as an instance), demonstrate your understanding of "3SAT is NP-complete", which is formally proved in "Theorem 10.15" in the textbook. Specifically, solve the following problems: a. Find 3-CNF for E (i.e., k=3, 3 literals) b. To prove "3SAT is NP-complete", two things must be done. First, you must showthat "3SAT is in NP." Show this is true.\fzaybaK,A., Khorshid, L. {2003}.A study on the effect of the Sc duration of subcutaneous heparin injection on bruising and pain. Joumal of Clinical Nursing. 1Tt3},3T3335. This study was clone to learn whether there is a difference in bruising or pain when subcutaneous injections of heparin are gjyen quicltly or slowly. Researchers studied 50 patients who required treatment with heparin. Injections oh the right abdomen were giyen over 10 seconds. on the left abdomen, over 30 seconds. Elruising occuned in almost two out of eyery three {54%} of those who received the rapid injection; howeyer, fewer than half {42%} of the patients bruised after receiying slower injection. Also. the size of the bruising was smaller in the Slit-second injection. Rain intensity and pain duration were statistically significantly lower for the slower injection than for the more rapid one. Chan, H. {2W1}. Effects of injection duration on site-pain intensity and bmising associated with subcutaneous heparin. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 251:6). 332392. This study was done to examine the relationship between how quickly a subcutaneous injection is performed and the occurrence of bruising and pain at the injection site. The research inyolyed 34 strolce patients receiying heparin. For each subject, two injection techniques were used: one injection 10 seconds in duration and the other. 3b seconds. Results showed the Slitsecond duration injection technique resulted in statistically significantly less intense sitepain and fewer and smaller bruises. Researchers concluded that administering a subcutaneous heparin injection oyer longer duration reduces injection site pain and bruising. lpp, M..Taddio_.A._. Sam, J., et al. {2DdT].vaccine-related pain: Randomized controlled trial of two injection techniques. Archives ofDisease in Childhood, 92(12) 1 1051 1:33. The aim of this study,r was to compare pain during immunization using a slow injection versus a rapid technique. One hundred and thirteen healthv infants 4 to 6 months of age receiving routine DPTaPHib immunization were studied. One group received the intramuscular dose using a technique with slow aspiration before injection: slow injection: and slow withdrawal. The technique used for infants in the other group involved no aspiration, rapid injection, and rapid withdrawal. Infants receiving the slower injection technique cried twice as often, cried longer, and tool: more time to have the vaccine injected. Researchers concluded that immunization using a rapid intramuscular injection technique is less painful than a slower technique and should be recommended for routine intramuscular immunization. You are providing care to an older adult patient who is receiving heparin therapy,r via subcutaneous injection. Based on the preceding studies, would you give subcutaneous doses over 10 seconds or 3D seconds? c. To prove NP-completeness, the second thing you should do is to perform a polynomial reduction of CSAT to 3SAT (as shown in the proof of Theorem 10.15). Using E above, perform the required polynomial reduction to find F. (I.e., conversionof E into F in polynomial time.) d. Demonstrate your understanding of 3SAT problem with the assignments of T and S. [Note that T is the assignment for the original Boolean expression E, while S is the assignment made by extending T. That is, you must check that "any truth assignmentT that satisfies E can be extended to a truth assignment S that satisfies F.]Descriptions of Algorithms While formally, the running time of a reduction is the time it takes to execute on a single-tape Turing machine, these algorithms are needlessly complex. We know that the sets of problems that can be solved on con- ventional computers, on multitape TM's and on single tape TM's in some polynomial time are the same, although the degrees of the polynomials may differ. Thus, as we describe some fairly sophisticated algorithms that are needed to reduce one NP-complete problem to another, let us agree that times will be measured by efficient implementations on a conventional computer. That understanding will allow us to avoid details regarding ma- nipulation of tapes and will let us emphasize the important algorithmic ideas 10.3.3 NP-Completeness of CSAT Now, we need to take an expression E that is the AND and OR of literals and convert it to CNF. As we mentioned, in order to produce in polynomial time an expression F from E that is satisfiable if and only if E is satisfiable, we must forgo an equivalence-preserving transformation, and introduce some new variables for F that do not appear in E. We shall introduce this "trick" in the proof of the theorem that CSAT is NP-complete, and then give an example of the trick to make the construction clearer. Theorem 10.13: CSAT is NP-complete. PROOF: We show how to reduce SAT to CSAT in polynomial time. First, use the method of Theorem 10.12 to convert a given instance of SAT to an expression E whose -'s are only in literals. We then show how to convert E to a CNF expression F in polynomial time and show that F is satisfiable if and only if E is. The construction of F is by an induction on the length of E. The particular property that F has is somewhat more than we need. Precisely, we show by induction on the number of symbol occurrences ("length" ) E that: . There is a constant c such that if E is a boolean expression of length n with -'s appearing only in literals, then there is an expression F such that: a) F is in CNF, and consists of at most n clauses. b ) F is constructible from E in time at most cEP. c) A truth assignment T for E makes E true if and only if there exists an extension S of 7 that makes F true. BASIS: If E consists of one or two symbols, then it is a literal. A literal is a clause, so E is already in CNF.INDUCTION: Assume that every expression shorter than E can be converted to a product of clauses, and that this conversion takes at most on time on an expression of length n. There are two cases, depending on the top-level operator of E. Case 1: E = E1 A E2. By the inductive hypothesis, there are expressions F1 and F, derived from E1 and E2, respectively, in CNF. All and only the satisfying assignments for E, can be extended to a satisfying assignment for F1, and similarly for E, and F2. Without loss of generality, we may assume that the variables of F1 and F2 are disjoint, except for those variables that appear in E; i.e., if we have to introduce variables into F, and /or F2, use distinct variables. Let F = F1 A F2. Evidently F1 A F2 is a CNF expression if F, and F, are. We must show that a truth assignment T' for E can be extended to a satisfying assignment for F if and only if T satisfies E. (If) Suppose T satisfies E. Let 71 be T restricted so it applies only to the variables that appear in E1, and let To be the same for E2. Then by the inductive hypothesis, 7, and 72 can be extended to assignments S, and S, that satisfy F1 and F2, respectively. Let S agree with S, and $, on each of the variables they define. Note that, since the only variables F, and F, have in common are the variables of E, and S, and S, must agree on those variables if both are defined, it is always possible to construct S. But S is then an extension of T that satisfies F. (Only-if) Conversely, suppose that T has an extension S that satisfies F. Let T1 ( resp., 72 ) be T restricted to the variables of E1 (resp., E2). Let S restricted to the variables of F1 (resp., F2) be S1 (resp., S2). Then S, is an extension of 71, and S, is an extension of 72. Because F is the AND of F, and F2, it must be that S, satisfies F1, and $2 satisfies F2. By the inductive hypothesis, I1 (resp., T2 ) must satisfy E1 (resp., E2). Thus, T satisfies E. Case 2: E = E1 V E2. As in case 1, we invoke the inductive hypothesis to assert that there are CNF expressions F, and F, with the properties: 1. A truth assignment for E1 (resp., E2 ) satisfies E1 (resp., E2 ), if and only if it can be extended to a satisfying assignment for F1 (resp., F2). 2. The variables of F, and F, are disjoint, except for those variables that appear in E. 3. F1 and Fa are in CNF. We cannot simply take the OR of F1 and F2 to construct the desired F, because the resulting expression would not be in CNF. However, a more com- plicated construction, which takes advantage of the fact that we only want to preserve satisfiability, rather than equivalence, will work. Suppose F1 = 91 Ag2 A . . . A 9pand F2 = h1 A h2 A . .. Ah,, where the g's and h's are clauses. Introduce a new variable y, and let F= (+g ) A( y+ $2 ) A . .. A ( y + gp) A (7 + hi) A (7+h2) A . . . A(7+h,) We must prove that a truth assignment T for E satisfies E if and only if T can be extended to a truth assignment S that satisfies F. (Only-if) Assume T satisfies E. As in Case 1, let 71 (resp., 72 ) be T restricted to the variables of E1 ( resp., E2). Since E = E1 V E2, either T satisfies E1 or I satisfies E2. Let us assume 7 satisfies E1. Then 71, which is T restricted to the variables of E1, can be extended to $1, which satisfies F1. Construct an extension S for 7, as follows; S will satisfy the expression F defined above: 1. For all variables r in F1, S(2) = 51 (x). 2. S(y ) = 0. This choice makes all the clauses of F that are derived from F2 true. 3. For all variables r that are in F2 but not in F1, S(x) is T( ) if the latter is defined, and otherwise may be 0 or 1, abribtrarily. Then S makes all the clauses derived from the g's true because of rule 1. S makes all the clauses derived from the h's true by rule 2-the truth assignment for y. Thus, S satisfies F . If T does not satisfy E1, but satisfies E2, then the argument is the same, except S(y ) = 1 in rule 2. Also, S(x) must agree with S2(2) whenever S2(2 ) is defined, but S(x ) for variables appearing only in Si is arbitrary. We conclude that S satisfies F in this case also. (If ) Suppose that truth assignment T for E is extended to truth assignment S for F, and S satisfies F. There are two cases, depending on what truth-value is assigned to y. First suppose that S(y ) = 0. Then all the clauses of F derived from the h's are true. However, y is no help for the clauses of the form (y + g: ) that are derived from the g's, which means that S must make true each of the gi's themselves; in essence, S makes F1 true. More precisely, let S, be S restricted to the variables of F1. Then S, satisfies F1. By the inductive hypothesis, 71, which is T restricted to the variables of En, must satisfy E1. The reason is that S, is an extension of T1. Since Ti satisfies E1, T must satisfy E, which is El V E2. We must also consider the case that S(y ) = 1, but this case is symmetric to what we have just seen, and we leave it to the reader. We conclude that T satisfies E whenever S satisfies F. Now, we must show that the time to construct F from E is at most quadratic, in n, the length of E. Regardless of which case applies, the splitting apart of E into E1 and E2, and construction of F from F1 and Fy each take time that is linear in the size of E. Let an be an upper bound on the time to construct E1and Ez from E plus the time to construct F from F, and F2, in either case 1 or case 2. Then there is a recurrence equation for 7(n), the time to construct F from any E of length n; its form is: T(1) = (2)

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts