Question: 5. Developed stakeholder register and matrix for this project PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM (PHS): TRANSFORMING HEALTH CARE SERVICES DELIVERY THROUGH INFORMATION MANAGEMENT Professor Richard Kesner wrote

5. Developed stakeholder register and matrix for this project

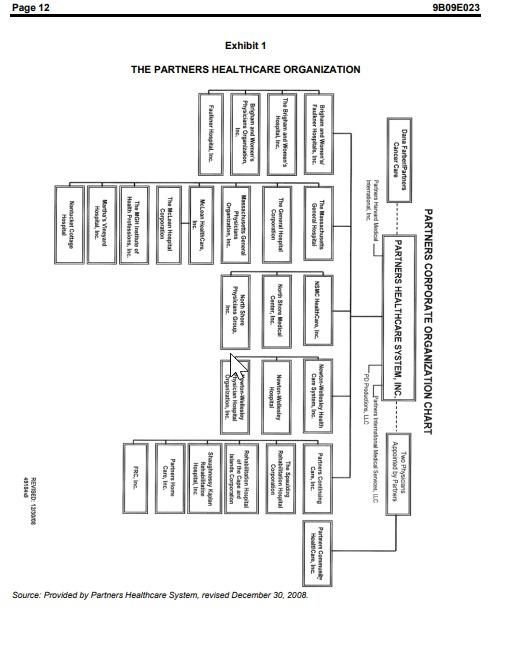

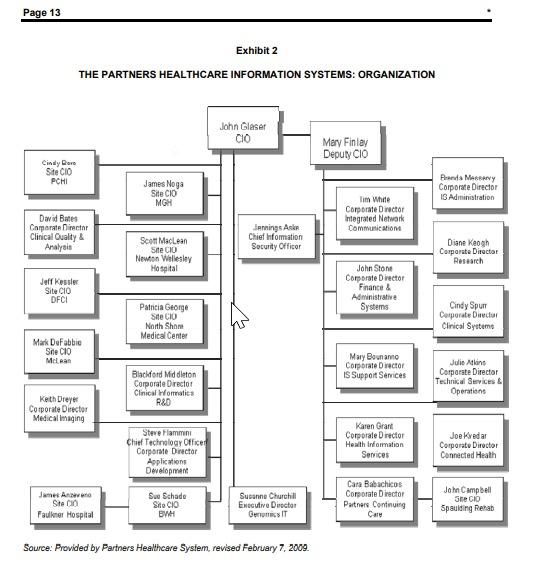

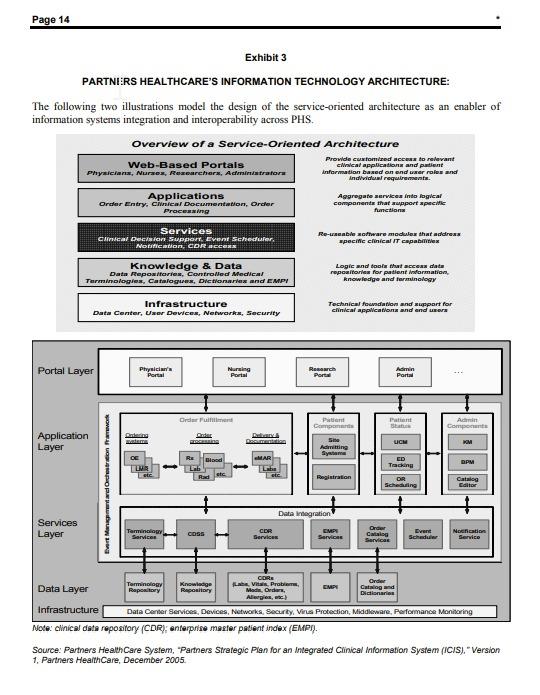

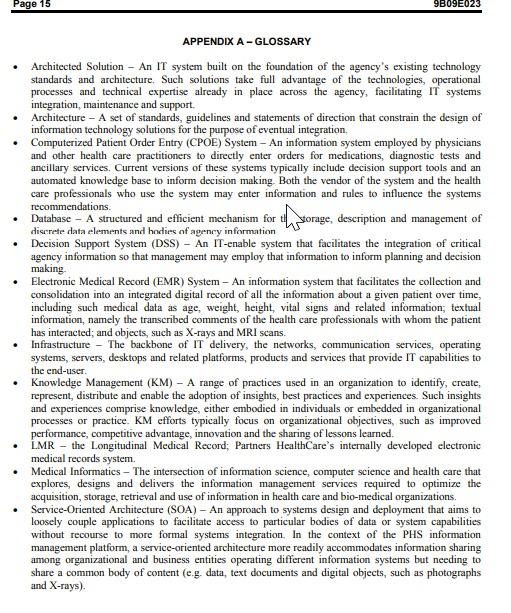

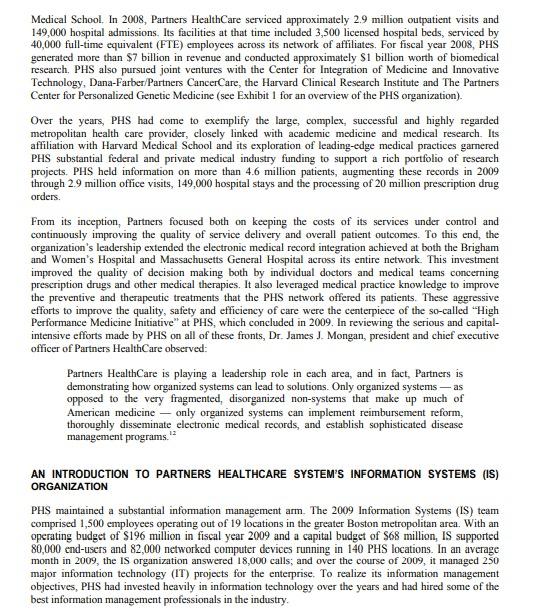

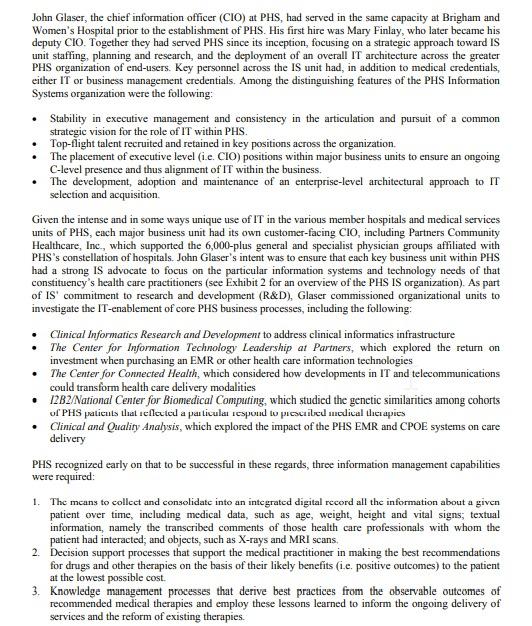

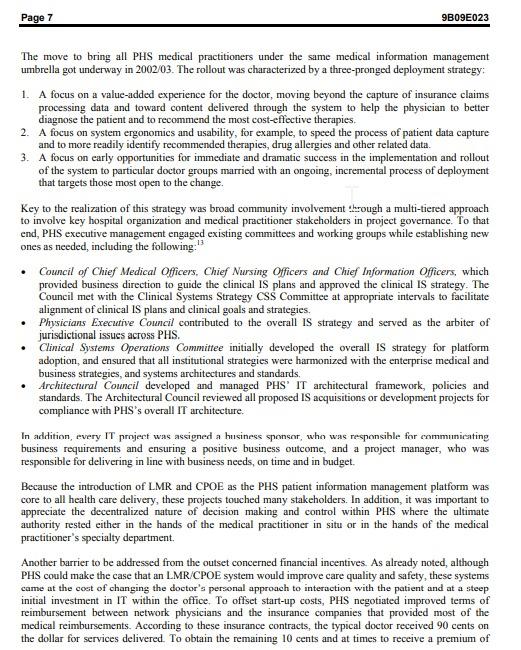

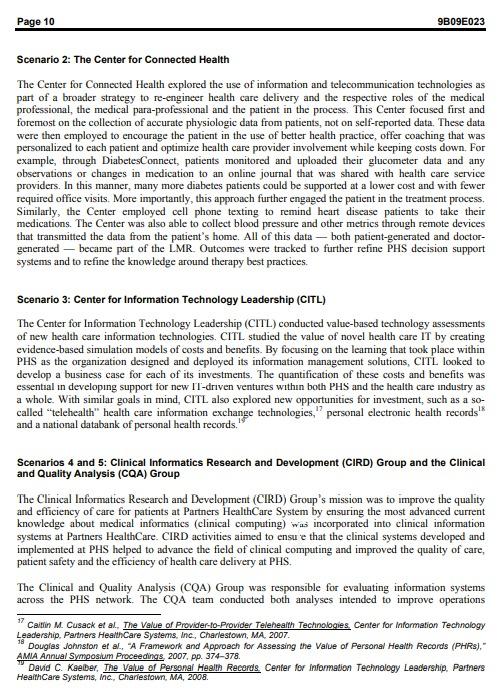

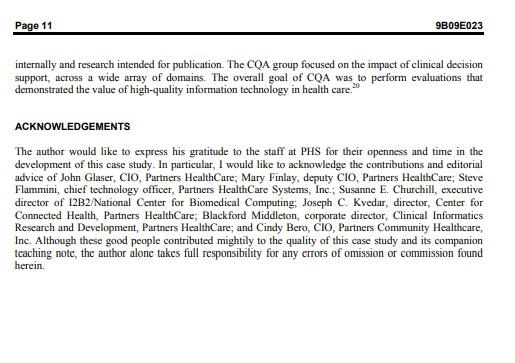

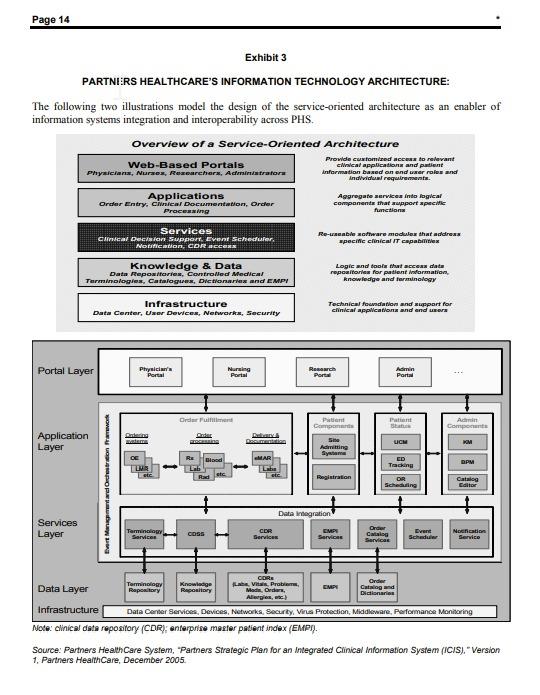

PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM (PHS): TRANSFORMING HEALTH CARE SERVICES DELIVERY THROUGH INFORMATION MANAGEMENT Professor Richard Kesner wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The author does not intend to illustrate ether effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The author may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentianty Ivey Management Services is the exclusive representative of the copyright holder and prohibas any form of reproduction, storage or transmital without its written permission. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Management Services, clo Richard Ivey School of Business, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 3K7, phone (519) 687- 3208, fax (519) 661-3882, e-mail cases@vey.uwo.ca. Copyright 2m9, Northeastern University College of Business Administration Version: (A) 2010-02-26 INTRODUCTION According to government sources, U.S. expenditures on health care in 2009 reached nearly $2.4 trillion (expected to reach $2.7 trillion in 2010). Despite this vaunting national level of expenditure on medical treatment, death rates due to preventable errors in the delivery of health services rose to approximately 98,000 deaths in 2009.? To address the dual challenges of cost control and quality improvement, some have argued that the U.S. health care system needs an integrated electronic medical record (EMR) system and associated information technology-enabled processes. Although the information systems currently available may meet the needs of the industry, the question remains regarding the requirements both within and by the health care services organization to achieve a satisfactory response to these dual challenges. Partners Healthcare System (PHS) maintained a centralized digital records library on more than 4.6 million patients, augmented in real time by data, textual comments and artifacts (i.e. X-rays, MRIs (magnetic resonance imagings), EKGs [electrocardiograms), etc.) as these patients visited doctor offices , received hospital-based or home care services, and obtained prescription medications and other therapies. Procedures were in place to ensure the data quality and integrity of these patient files. Going forward, any health care professional across the network could access a patient's complete record, ensuring accurate, timely and comprehensive information sharing about that patient's medical history, allergies, current treatments and other related information. In and of itself, the investment in this electronic medical records (EMR) system was expected to reduce delays in service delivery, mistakes in treating the patient and overall health care costs. When coupled with a computerized patient order entry (CPOE) system to inform Plunkett Research, Lid "U.S. Healthcare Industry Overview 2008 www.plunkettre search.comIndustries/Health Care/tabid/205/Default.aspx. Lucian L. Leape and Donald M. Berwick, "Five Years after to Erris Human: What Have We Learned? Lumal of the American Medical Association. May 18, 2005, pp. 2384-2390. William W. Stead and Herbert S. Lin, editors. Computational Technology for Effective Health Care: Immediate Steps and Strategic Directions, National Academy of Sciences, National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2009. the selection of drugs and appropriate treatment, PHS health care professionals were now positioned to target more specific therapies for their patients, to identify the most effective, low-cost options among potential treatment strategies and to draw on a vast body of experience-based knowledge across the network to inform patient care. BACKGROUND: THE CHALLENGES FACING THE HEALTH CARE INDUSTRY U.S. expenditures on health care in 2008 exceeded $2 trillion. Of that amount, approximately $747 billion was spent on hospital services, $502 billion on physician and clinical services, $199 billion on nursing home and home health care services, and $247 billion on prescription drugs. The cost of health care was expected to spiral even further out of control as the 1950s baby-boomer population became elderly. Alongside the growing furor over escalating costs, the health care industry also faced persistent questions about the quality of the services it provided. Although the quality debate had persisted for some time, recent studies estimated that preventable medical errors led to as many as 98,000 deaths per year in the United States, clearly suggesting that better informed and more knowledgeable health care practices could not only save money for the government, insurance companies and individual-paying patients but could also save lives. In its most recent and comprehensive statement to date on the need to transform health care delivery in the United States through better information management, a study sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences observed: Health care is an information and knowledge-intensive enterprise. In the future, health care providers will need to rely increasingly on information technology (IT) to acquire, manage, analyze, and disseminate health care information and knowledge. Many studies have identified deficiencies in the current health care system, including inadequate care, superfluous or incorrect care, immense inefficiencies and hence high costs, and inequities in access to care. In response, federal policy makers have tended to focus on the creation and interchange of electronic health information and the use of IT as critical infrastructural improvements whose deployments help to address some (but by no means all) of these deficiencies. The authors of this report determined that the crisis in health care delivery was not just a matter of the cost of these services but also a matter of quality. Even within the typical medical practice or hospital, information about the patient was not integrated nor was it effectively leveraged to prescribe cost-effective therapies. Over the last two decades, a growing consensus has emerged that health care institutions fail to deliver the "most [cost] effective care and suffer substantially as a result of medical errors." The National Academy of Sciences study observed that: These persistent problems do not reflect incompetence on the part of health care professionals rather, they are a consequence of the inherent intellectual complexity of health care taken as a whole and a medical care environment that has not been adequately structured to help clinicians avoid mistakes or to systematically improve their decision making and practice. Administrative and organizational fragmentation, together with complex, distributed, and unclear authority and responsibility, further complicates the health care environment." The current state of health care industry performance could be considered from both a cost and quality standpoint, as a consequence of three sets of intersecting factors: 1. First, the nature of health care decisions were fraught with uncertainty about the patient's current state of health and past medical history, the patient's genetic predisposition (or lack thereof) to particular medical therapies and the actual effectiveness of past and future treatments for that particular patient. 2. Second, the economic structure of health care delivery in the United States was extremely complex and could be argued to be counter-intuitive to the encouragement of low-cost options. Instead, the system actively encouraged high-cost procedures under the guise of promoting risk-avoiding, "better" medicine 3. Third and finally, the very information systems and standards that could afford better integrated service delivery, the identification of lower-cost medical options and the avoidance of mistakes in the prescription of medications and other therapies were implemented in such ways as to throw up significant barriers to information sharing and data-driven decision support." Despite the many very real barriers to the improvement of health care services delivery, the U.S. Federal government, health care services organizations, medical practitioners, health insurance companies and information technology companies that serviced this industry were coming together to help address these concerns. This effort required a significant investment of resources over an extended period of time, perhaps a decade or more." Major US research hospitals and their affiliated service delivery arms were transforming health care delivery in ways that could serve as a blueprint for industry-wide change. Among these institutions, Partners Health Care System (PHS) illustrated the potential opportunities and the ongoing challenges in achieving more integrated, higher-quality and less expensive health care services delivery. AN INTRODUCTION TO PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM (PHS) Partners Health Care (PHS) was founded in 1994 by the partnering of Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital to become an integrated health care delivery system that offered patients a continuum of coordinated high-quality care. As of 2009, the system included 6,300 primary care and specialty physicians; 11 hospitals, including its two founding academic medical centers, specialty facilities, community health centers and other health care-related entities, and an ongoing affiliation with Harvard * Wiliam W. Stead and Herbert S. Lin, editors. Computational Technology for Effective Health Care: Immediate Steps and Strategic Directions National Academy of Sciences, National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2009. p. 3 Ibid "Rainu Kaushal et al., "The Costs of a National Health Information Network." Annals of Internal Medicine, August 2, 2005, pp. 165-73 Medical School, In 2008, Partners HealthCare serviced approximately 2.9 million outpatient visits and 149,000 hospital admissions. Its facilities at that time included 3,500 licensed hospital beds, serviced by 40,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees across its network of affiliates. For fiscal year 2008, PHS generated more than $7 billion in revenue and conducted approximately $1 billion worth of biomedical research. PHS also pursued joint ventures with the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology, Dana-Farber, Partners Cancer Care, the Harvard Clinical Research Institute and The Partners Center for Personalized Genetic Medicine (see Exhibit I for an overview of the PHS organization). Over the years, PHS had come to exemplify the large, complex, successful and highly regarded metropolitan health care provider, closely linked with academic medicine and medical research. Its affiliation with Harvard Medical School and its exploration of leading-edge medical practices garnered PHS substantial federal and private medical industry funding to support a rich portfolio of research projects. PHS held information on more than 4.6 million patients, augmenting these records in 2009 through 2.9 million office visits, 149,000 hospital stays and the processing of 20 million prescription drug orders. From its inception, Partners focused both on keeping the costs of its services under control and continuously improving the quality of service delivery and overall patient outcomes. To this end, the organization's leadership extended the electronic medical record integration achieved at both the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital across its entire network. This investment improved the quality of decision making both by individual doctors and medical teams concerning prescription drugs and other medical therapies. It also leveraged medical practice knowledge to improve the preventive and therapeutic treatments that the PHS network offered its patients. These aggressive efforts to improve the quality, safety and efficiency of care were the centerpiece of the so-called "High Performance Medicine Initiative" at PHS, which concluded in 2009. In reviewing the serious and capital- intensive efforts made by PHS on all of these fronts, Dr. James J. Mongan, president and chief executive officer of Partners Health Care observed: Partners HealthCare is playing a leadership role in each area, and in fact, Partners is demonstrating how organized systems can lead to solutions. Only organized systems - as opposed to the very fragmented, disorganized non-systems that make up much of American medicine - only organized systems can implement reimbursement reform, thoroughly disseminate electronic medical records, and establish sophisticated disease management programs. AN INTRODUCTION TO PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM'S INFORMATION SYSTEMS (IS) ORGANIZATION PHS maintained a substantial information management arm. The 2009 Information Systems (IS) team comprised 1,500 employees operating out of 19 locations in the greater Boston metropolitan area. With an operating budget of S196 million in fiscal year 2009 and a capital budget of $68 million, IS supported 80,000 end-users and 82,000 networked computer devices running in 140 PHS locations. In an average month in 2009, the Is organization answered 18,000 calls, and over the course of 2009, it managed 250 major information technology (IT) projects for the enterprise. To realize its information management objectives, PHS had invested heavily in information technology over the years and had hired some of the best information management professionals in the industry. John Glaser, the chief information officer (CIO) at PHS, had served in the same capacity at Brigham and Women's Hospital prior to the establishment of PHS. His first hire was Mary Finlay, who later became his deputy CIO. Together they had served PHS since its inception, focusing on a strategic approach toward IS unit staffing, planning and research, and the deployment of an overall IT architecture across the greater PHS organization of end-users. Key personnel across the IS unit had, in addition to medical credentials, either IT or business management credentials. Among the distinguishing features of the PHS Information Systems organization were the following: Stability in executive management and consistency in the articulation and pursuit of a common strategic vision for the role of IT within PHS. Top-flight talent recruited and retained in key positions across the organization. The placement of executive level (i.e. CIO) positions within major business units to ensure an ongoing C-level presence and thus alignment of IT within the business. The development, adoption and maintenance of an enterprise-level architectural approach to IT selection and acquisition Given the intense and in some ways unique use of IT in the various member hospitals and medical services units of PHS, each major business unit had its own customer-facing CIO, including Partners Community Healthcare, Inc., which supported the 6,000-plus general and specialist physician groups affiliated with PHS's constellation of hospitals. John Glaser's intent was to ensure that each key business unit within PHS had a strong IS advocate to focus on the particular information systems and technology needs of that constituency's health care practitioners (see Exhibit 2 for an overview of the PHS IS organization) . As part of IS' commitment to research and development (R&D), Glaser commissioned organizational units to investigate the IT-enablement of core PHS business processes, including the following: Clinical Informatics Research and Development to address clinical informatics infrastructure The Center for Information Technology Leadership at Partners, which explored the return on investment when purchasing an EMR or other health care information technologies The Center for Connected Health, which considered how developments in IT and telecommunications could transform health care delivery modalities 12B2/National Center for Biomedical Computing, which studied the genetic similarities among cohorts of PHS patients that reflected a paulicula respond to picuild modical dictapics Clinical and Quality Analysis, which explored the impact of the PHS EMR and CPOE systems on care delivery PHS recognized early on that to be successful in these regards, three information management capabilities were required: 1. The mcans to collect and consolidate into an integrated digital record all the information about a given patient over time, including medical data, such as age, weight, height and vital signs; textual information, namely the transcribed comments of those health care professionals with whom the patient had interacted, and objects, such as X-rays and MRI scans, 2. Decision support processes that support the medical practitioner in making the best recommendations for drugs and other therapies on the basis of their likely benefits (1.e. positive outcomes) to the patient at the lowest possible cost. 3. Knowledge management processes that derive best practices from the observable outcomes of recommended medical therapies and employ these lessons learned to inform the ongoing delivery of services and the reform of existing therapies. . PHS's medical and is leadership saw the company's investment in IT as the enabling information system foundation to achieve these capabilities. PHS'S FORAY INTO ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORDS (EMR) AND COMPUTERIZED PATIENT ORDER ENTRY (CPOE) The founding members of Partners HealthCare, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital pioneered electronic medical records (EMR) solutions. Massachusetts General Hospital began work on an early version of an EMR system in 1976, and Brigham and Women's Hospital initiated an EMR in 1989. When these hospitals cu ubined to form PHS in 1994, they adopted an internally developed EMR platform, which they dubbed the Longitudinal Medical Record (LMR). Thereafter, as the PHS network grew, member hospitals adopted LMR for their use in managing their digitized patient records. The operational requirements faced by PHS member institutions in this regard were two-fold. On the one hand, each institution was obliged to establish processes to capture all ongoing health care information digitally and to convert past paper-based medical records to a shareable digital format. On the other hand, due to the increasing interaction among members of the PHS services network, patient information residing anywhere within the network needed to be made available to all PHS service providers. To address these requirements, PHS business units underwent significant process changes, and the enterprise as a whole adopted an information management and technology architecture and platform that proved flexible enough to deal with the differences posed by the various information systems and digital record formats extant within PHS. Key among these innovations was the adoption and widespread use of a computerized patient order entry (CPOE) system that captured patient prescriptions and other physician- assigned medical therapies. Although these efforts were not without their difficulties, they paled in comparison to the challenges posed by bringing the 6,000 medical practitioners under the PHS LMR/CPOE umbrella. The barriers to adoption included the following 1. Two-thirds of the doctors in question had some formal affiliation with a PHS hospital, whereas the rest were scattered around the greater Boston metropolitan area and operated out of their own local offices. 2. Of those doctors with a formal affiliation with a PHS hospital, many employed an out-of-hospital office or offices as their primary venue for meeting with patients 3. Local doctors' offices typically lacked the information technology and telecommunications infrastructures to support the LMR and CPOE systems. System training and support were also issues, especially when these tasks took time away from either seeing patients or keeping abreast of developments in a specialized field. 4. Many of these health care practitioners, though perhaps not technophobic, were not enamored of interacting with a compiter terminal while they were seeing a patient and were even less interested in using a computer system for taking notes and issuing prescriptions when handwritten work was perceived as more efficient, casier and less stressful. 5. The cost of implementing an LMR/CPOE connection in a physician's office cost an average of $40,000 per doctor. Existing anti-kickback legislation prevented PHS from subsidizing the adoption of this information management platform. Page 7 9B09E023 The move to bring all PHS medical practitioners under the same medical information management umbrella got underway in 2002/03. The rollout was characterized by a three-pronged deployment strategy: 1. A focus on a value-added experience for the doctor, moving beyond the capture of insurance claims processing data and toward content delivered through the system to help the physician to better diagnose the patient and to recommend the most cost-effective therapies. 2. A focus on system ergonomics and usability, for example, to speed the process of patient data capture and to more readily identify recommended therapies, drug allergies and other related data. 3. A focus on early opportunities for immediate and dramatic success in the implementation and rollout of the system to particular doctor groups married with an ongoing, incremental process of deployment that targets those most open to the change. Key to the realization of this strategy was broad community involvement through a multi-tiered approach to involve key hospital organization and medical practitioner stakeholders in project governance. To that end, PHS executive management engaged existing committees and working groups while establishing new ones as needed, including the following: Council of Chief Medical Officers, Chief Nursing Officers and Chief Information Officers, which provided business direction to guide the clinical IS plans and approved the clinical IS strategy. The Council met with the Clinical Systems Strategy CSS Committee at appropriate intervals to facilitate alignment of clinical IS plans and clinical goals and strategies. Physicians Executive Council contributed to the overall is strategy and served as the arbiter of jurisdictional issues across PHS. Clinical Systems Operations Committee initially developed the overall is strategy for platform adoption, and ensured that all institutional strategies were harmonized with the enterprise medical and business strategies, and systems architectures and standards. Architectural Council developed and managed PHS' IT architectural framework, policies and standards, The Architectural Council reviewed all proposed IS acquisitions or development projects for compliance with PHS's overall IT architecture. In addition, every IT project was assigned a business sponsor, who was responsible for communicating business requirements and ensuring a positive business outcome, and a project manager, who was responsible for delivering in line with business needs, on time and in budget. Because the introduction of LMR and CPOE as the PHS patient information management platform was core to all health care delivery, these projects touched many stakeholders. In addition, it was important to appreciate the decentralized nature of decision making and control within PHS where the ultimate authority tested either in the hands of the medical practitioner in situ or in the hands of the medical practitioner's specialty department Another barrier to be addressed from the outset concerned financial incentives. As already noted, although PHS could make the case that an LMR/CPOE system would improve care quality and safety, these systems came at the cost of changing the doctor's personal approach to interaction with the patient and at a steep initial investment in IT within the office. To offset start-up costs, PHS negotiated improved terms of reimbursement between network physicians and the insurance companies that provided most of the medical reimbursements. According to these insurance contracts, the typical doctor received 90 cents on the dollar for services delivered. To obtain the remaining 10 cents and at times to receive a premium of greater than 10 cents on the dollar, the doctor was obliged to follow a series of medical protocols in conjunction with the patient. For example, the doctor needed to track that a patient who suffered from diabetes or heart disease had taken all of the prescribed precautionary and preventative steps (eg, follow-up visits to the doctor, related medical check-ups and the monitoring of vital signs) associated with ongoing treatment. Keeping track of all of these activities without an integrated EMR or CPOE was difficult and expensive for the primary physician. Those doctors adopting PHS system within their office achieved a higher level of compensation from the insurance providers for services rendered and at lower operating costs than those who did not adopt the new systems During the rollout of the new systems, the PHS team also provided a number of support services to ease the transition for doctors' offices. For example, they assisted each office in selecting the platform that would best meet its needs, taking into account the underlying cost structure and the pros and cons for each option. In addition, PHS offered orientation workshops and ongoing training sessions for practitioners and their support staffs as well as user and technical support through a help desk. Between 2003 and the end of 2007, almost 90 per cent of the existing PHS provider network moved over to the LMR system and began the process of sharing their health care information digitally within PHS. First, the project team identified and worked with carly adopters, who were open to the use of the new technology platform. Next, they targeted primary care physicians because patients would visit these physicians before being referred to a specialty practice. Lastly, they targeted specialty practices, again piloting with carly adopters and learning from these experiences. Of those practices that fell into the remaining 10 per cent, the majority were small offices where the doctors were nearing retirement or did not see any financial benefit from joining the integrated system. During 2007, PHS worked with these remaining offices to get them on board. Some simply left the system, disaffiliating themselves from PHS. Others sold off their practices to physicians more inclined to join in the system. By the end of 2009, the entire PHS practitioner network employed LMR, actively integrating their digital patient records with the rest of PHS The successful implementation of these information systems depended largely on their adoption and use by health care practitioners across the PHS network. To that end, the rollout plan involved service delivery process reengineering as well as the extensive initial training and ongoing support of end-users. In addition, the iS unit provided a robust, integrated platform for the collection, processing and dissemination of information across the PHS network, and they also worked to ensure the quality and integrity of the data going into these systems and processes. The new data management platform embraced a so-called "service oriented architecture." The attributes of this platform included the following A single, enterprise repository and list for each of the key data types (allergies, medications and problems) All software capable of reading from and writing to these lists Standard data definitions applied to support the back-end aggregation of key clinical data for decision support, and quality reporting Standards for clinical knowledge across the enterprise Knowledge management process and procedure for achieving clinical consensus on the rules governing system decision-making processes Variation in the workflow of applications that were consistent with PIIS medical and service delivery practices Page 9 9B09E023 Workflow-based applications should demand some key work processes and data displays that lead to demonstrated superior results This approach allowed for the exchange of information within the PHS network of users without the need to address the discreie data and process rules associated with the many different information systems operating across the enterprise. Furthermore, as new enterprise-wide systems joined those already in place, these future clinical applications would take advantage of the shared repositories of enterprise data, knowledge and process workflows that were built as part of the services-oriented architecture. (For more technical information on the service-oriented architecture, see Exhibit 3.) The implementation of the LMR within PHS also called for data to be of a high level of quality. The mechanisms for data collection, validation, cleansing and warehousing, as part of enterprise-wide process improvement, were all made more rigorous. In addition, the IS organization faced the need to review the rules engine that enabled its CPOE platform. Over the years, millions of rules, concerning such subjects as prescribed dosages, drug interactions and the recommended sequencing of therapies had found their way into the CPOE knowledge base. The provenance for many of these rules remained obscure, and the relevance and accuracy of others were in doubt. Given the vital importance of a current and accurate set of rules with CPOE decision-support system, IS took on the re-documentation and clean-up of the system's knowledge base, as well as the establishment of a more rigorous process for the ongoing maintenance of rules engine. Like the rollout of LMR, the improvement of the PHS knowledge management process progressed in phases. The clean-up phase gave way to a more formal assignment of content stewardship by subject matter experts, which led ultimately to the regular authoring and updating of best practices that better informed health care delivery across the PHS network. THE EMERGING TRANSFORMATIONAL HEALTH CARE DELIVERY LANDSCAPE - EMPLOYING EMR AND CPOE DATA TO INFORM BEST PRACTICES Scenario 1: The 12B2/National Center for Biomedical Computing PHS's 4.6 million-plus active patient records constituted a rich resource for the tracking and study of specific medical therapies. The 12B2/National Center for Biomedical Computing focused on this resource to study the genome types (genetic characteristies) of patient cohorts that responder in a similar manner to a particular medication or other therapies. For example, the Center examined a sub-group taking a particular anti-depressant and of that cohort, the sub-set of patients who were unresponsive to the drug. With the permission of these patients, the Center studied their DNA to investigate whether something in their genetic code explained the drug's ineffectiveness. More traditional, random samplings of potential drug users might involve 500,000 people and costs billions of dollars in research. Instead, the Center leveraged the data within the PHS LMR/CPOE systems. Over time, the findings of the Center would more precisely focus the administration of drugs to result in the most favorable outcome in patient treatment, would avoid the prescription of therapies to genome types where the drug had proven ineffective or even dangerous, would help direct new drug development and would as a result lower the cost and risk of drug development and its administration among patients in need of treatment, 14 * Partners Healthcare System, Partners Advanced Clinical Informatics Infrastructure," Partners Health Care, Boston, p. 6. 15 Tonya Hangsermeier et al. Collaborative Authoning of Decision Support Knowledge. A Demonstration," Partners HeartCare, Boston, 2009. 16 Shawn Murphy et al. "Instrumenting the Health Care Enterprise for Discovery Research in the Genomic Ene Partners HealthCare, Boston, 2008 Page 10 9B09E023 Scenario 2: The Center for Connected Health The Center for Connected Health explored the use of information and telecommunication technologies as part of a broader strategy to re-engineer health care delivery and the respective roles of the medical professional, the medical para-professional and the patient in the process. This Center focused first and foremost on the collection of accurate physiologic data from patients, not on self-reported data. These data were then employed to encourage the patient in the use of better health practice offer coaching that was personalized to each patient and optimize health care provider involvement while keeping costs down. For example, through Diabetes Connect, patients monitored and uploaded their glucometer data and any observations or changes in medication to an online journal that was shared with health care service providers. In this manner, many more diabetes patients could be supported at a lower cost and with fewer required office visits. More importantly, this approach further engaged the patient in the treatment process. Similarly, the Center employed cell phone texting to remind heart disease patients to take their medications. The Center was also able to collect blood pressure and other metrics through remote devices that transmitted the data from the patient's home. All of this data - both patient-generated and doctor- generated - became part of the LMR Outcomes were tracked to further refine PHS decision support systems and to refine the knowledge around therapy best practices. Scenario 3: Center for Information Technology Leadership (CITL) The Center for Information Technology Leadership (CITL) conducted value-based technology assessments of new health care information technologies. CITL studied the value of novel health care IT by creating evidence-based simulation models of costs and benefits. By focusing on the leaming that took place within PHS as the organization designed and deployed its information management solutions, CITL looked to develop a business case for each of its investments. The quantification of these costs and benefits was essential in developing support for new IT-driven ventures within both PHS and the health care industry as a whole. With similar goals in mind, CITL also explored new opportunities for investment, such as a so- called telehealth" health care information exchange technologies," personal electronic health records" and a national databank of personal health records. Scenarios 4 and 5: Clinical Informatics Research and Development (CIRD) Group and the Clinical and Quality Analysis (CQA) Group The Clinical Informatics Research and Development (CIRD) Group's mission was to improve the quality and efficiency of care for patients at Partners HealthCare System by ensuring the most advanced current knowledge about medical informatics (clinical computing) was incorporated into clinical information systems at Partners HealthCare. CIRD activities aimed to ensu 'e that the clinical systems developed and implemented at PHS helped to advance the field of clinical computing and improved the quality of care, patient safety and the efficiency of health care delivery at PHS. The Clinical and Quality Analysis (CQA) Group was responsible for evaluating information systems across the PHS network. The CQA team conducted both analyses intended to improve operations Caitlin M. Cusack et al. The value of Provider-to-Provider Telehealth Technologies. Center for Information Technology Leadership, Partners Health Care Systems, Inc, Charlestown, MA, 2007. Douglas Johnston et al., "A Framework and Approach for Assessing the value of Personal Health Records (PHRS)," AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2007. pp. 374-378. David C. Keeber, The Value of Personal Health Records. Center for Information Technology Leadership. Partners Health Care Systems, Inc., Charlestown, MA, 2008 Page 11 9B09E023 internally and research intended for publication. The CQA group focused on the impact of clinical decision support, across a wide array of domains. The overall goal of CQA was to perform evaluations that demonstrated the value of high-quality information technology in health care.20 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express his gratitude to the staff at PHS for their openness and time in the development of this case study. In particular, I would like to acknowledge the contributions and editorial advice of John Glaser, CIO, Partners Health Care; Mary Finlay, deputy CIO, Partners HealthCare; Steve Flammini, chief technology officer, Partners HealthCare Systems, Inc.: Susanne E. Churchill, executive director of 12B2/National Center for Biomedical Computing: Joseph C. Kvedar, director, Center for Connected Health, Partners HealthCare, Blackford Middleton, corporate director, Clinical Informatics Research and Development, Partners HealthCare; and Cindy Bero, CIO, Partners Community Healthcare, Inc. Although these good people contributed mightily to the quality of this case study and its companion teaching note, the author alone takes full responsibility for any errors of omission or commission found herein 9B09E023 PARTNERS CORPORATE ORGANIZATION CHART Dana Farber Partners Cancer Care PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM, INC. Two Physicians Appointed by Parts Partner Made International, Inc Pas Medical Service, IL PD Productions, Brigham and Wonen Faulkner Harpis, the The Massachu General Hospital NSC Healthcare, Inc. Newton- Wesley Health Canyon, Inc Partners Conti Care, Inc. Partner Commun HallCare, ne The Brigham and Wine's Hospital, Inc. The General Hospital Corporation North Shore Wil Center, Inc. Newton Willy Hospital The Spalding Rohan Hospital Carpowin Exhibit 1 THE PARTNERS HEALTHCARE ORGANIZATION Brigham and Women's Physicians Organi Inc. Massachusetts General Physicians Organization, Inc. North Shore Firypticians Greur, Lugton-Walesby Styling Orgasbation, in Rohabitation Hospital of the Cape and Islands Corporation Falopital, Inc McLeane Care Inc. Shaughnessy Kaplan Rehabilitate Hospital, le The McLean Hopital Corporation Partners Home Care, Inc. Source: Provided by Partners Healthcare System, revised December 30, 2008 The MGH of Health Professions, he. FRC, In Maths Veeyard Hospitaline Nantucket Cottage Hospi Page 12 REVISED: 133108 43110 Page 13 Exhibit 2 THE PARTNERS HEALTHCARE INFORMATION SYSTEMS: ORGANIZATION John Glaser CIO Mary Finley Deputy CIO Cindy Dore Site CIO PCHI James Noga Site CIO MGH Pred MARY Corporate Director 15 Administration Tim White Corporate Director Integrated Network Communication David Bates Comparate Director Clinical Ouality & Analysis Iarnings Aske Chief Information Security Officer Scor MacLean Site CIO Newton Wellesley Hospital Diane Krogh Corporate Director Research Jeff Kessler Site CIO DFCI John Stone Corporate Director Finance Administrative Systems Pancia George Site CID North Shore Medical Center Cindy Spurt Corporate Director Clinical Systeme Mark DuFabbie Sme CIO Milean Mary Bonanno Corporate Director IS Support Services Blackford Middleton Corporate Director Clinical Wormatics R&D Julie Atkins Corporate Director Technical Services Operations Keth Dreyer Corporate Director Medical Imaging Steve Flammi Chief Technology Officer Corporate Director Applications Development Karen Grant Corporate Director Health Information Services Joe Kredar Corporate Director Connected Heath James Answer Site Faulkner Hospital Sus Schade Sito CIO BW Susanne Churchill Executive Director GenIT Cara Babachicos Corporate Director Partners Continuing Car John Campbell Site CIO Spauiding Rehab Source: Provided by Partners Healthcare System, revised February 7, 2009. Page 14 Exhibit 3 PARTNERS HEALTHCARE'S INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY ARCHITECTURE: The following two illustrations model the design of the service-oriented architecture as an enabler of information systems integration and interoperability across PHS. Overview of a Service-Oriented Architecture Web-Based Portals Information based on end wwer roles and Provide customized acces to relevant clinical applications and patient Individual requirement. Phyaliana, Nurses, Researchers, Administratora Applications Order Entry, Clinical Documentation, Order Processing Aggregate service Indological components that support specific functions Services Clinical Decision Support. Event Scheduler. Notification, COR CCER Re-usable software modules that address specific clinical IT capable Knowledge & Data Data Repositories, Controlled Medical Terminologies, Catalogues Dictionaries and EMPY Logic and tool that accea date repositories for patient Information knowledge and terminology Infrastructure Data Center, User Devices, Network Security Technical foundation and art for clinical application and end users Portal Layer Physic Portal Nursing Portal Research Portal Admin Portal Order Film Pa Compom Ach Components Application Layer Onder MERC UCH Wom Adimitting Syabame RE MAR Blood CD Tracking DPM Rad Registration Der Mannaradero amor Scheduling Catalog Editor Data Integration Services Layer Tarmogy Services COSS CDR Services CMP Services Order Causes Services Even Schuhe Nocation Service COR Data Layer Order Terminology Lab, V. Problem Knowledge Repository EM Repository Madie Orders Catalog and Dictionaries Alergies, Infrastructure Data Center Services, Devices, Networks. Securty, Virus Protection Middleware. Performance Monitoring Note: clinical data repository (CDR),enterprise master patient index (EMP). Source: Partners Health Care System, Partners Strategic Plan for an integrated Clinical Information System (CIS). Version 1. Partners HealthCare, December 2005 Page 15 9B09E023 APPENDIX A-GLOSSARY . . . Architected Solution - An IT system built on the foundation of the agency's existing technology standards and architecture. Such solutions take full advantage of the technologies, operational processes and technical expertise already in place across the agency, facilitating IT systems integration, maintenance and support. Architecture - A set of standards, guidelines and statements of direction that constrain the design of information technology solutions for the purpose of eventual integration, Computerized Patient Order Entry (CPOE) System - An information system employed by physicians and other health care practitioners to directly enter orders for medications, diagnostic tests and ancillary services. Current versions of these systems typically include decision support tools and an automated knowledge base to inform decision making. Both the vendor of the system and the health care professionals who use the system may enter information and rules to influence the systems recommendations Database - A structured and efficient mechanism for t Storage, description and management of discrete data elements and hodies of agency information Decision Support System (DSS) - An IT-enable system that facilitates the integration of critical agency information so that management may employ that information to inform planning and decision making Electronic Medical Record (EMR) System - An information system that facilitates the collection and consolidation into an integrated digital record of all the information about a given patient over time, including such medical data as age, weight, height, vital signs and related information; textual information, namely the transcribed comments of the health care professionals with whom the patient has interacted; and objects, such as X-rays and MRI scans. Infrastructure - The backbone of IT delivery, the networks, communication services, operating systems, servers, desktops and related platforms, products and services that provide IT capabilities to the end-user Knowledge Management (KM) - A range of practices used in an organization to identify, create, represent, distribute and enable the adoption of insights, best practices and experiences. Such insights and experiences comprise knowledge, either embodied in individuals or embedded in organizational processes or practice. KM efforts typically focus on organizational objectives, such as improved performance, competitive advantage, innovation and the sharing of lessons learned. LMR - the Longitudinal Medical Record; Partners HealthCare's internally developed electronic medical records system, Medical Informatics - The intersection of information science, computer science and health care that explores, designs and delivers the information management services required to optimize the acquisition, storage, retrieval and use of information in health care and bio-medical organizations. Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) - An approach to systems design and deployment that aims to loosely couple applications to facilitate access to particular bodies of data or system capabilities without recourse to more formal systems integration. In the context of the PHS information management platform, a service-oriented architecture more readily accommodates information sharing among organizational and business entities operating different information systems but needing to share a common body of content (eg data, text documents and digital objects, such as photographs and X-rays). . PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM (PHS): TRANSFORMING HEALTH CARE SERVICES DELIVERY THROUGH INFORMATION MANAGEMENT Professor Richard Kesner wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The author does not intend to illustrate ether effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The author may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentianty Ivey Management Services is the exclusive representative of the copyright holder and prohibas any form of reproduction, storage or transmital without its written permission. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Management Services, clo Richard Ivey School of Business, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada, N6A 3K7, phone (519) 687- 3208, fax (519) 661-3882, e-mail cases@vey.uwo.ca. Copyright 2m9, Northeastern University College of Business Administration Version: (A) 2010-02-26 INTRODUCTION According to government sources, U.S. expenditures on health care in 2009 reached nearly $2.4 trillion (expected to reach $2.7 trillion in 2010). Despite this vaunting national level of expenditure on medical treatment, death rates due to preventable errors in the delivery of health services rose to approximately 98,000 deaths in 2009.? To address the dual challenges of cost control and quality improvement, some have argued that the U.S. health care system needs an integrated electronic medical record (EMR) system and associated information technology-enabled processes. Although the information systems currently available may meet the needs of the industry, the question remains regarding the requirements both within and by the health care services organization to achieve a satisfactory response to these dual challenges. Partners Healthcare System (PHS) maintained a centralized digital records library on more than 4.6 million patients, augmented in real time by data, textual comments and artifacts (i.e. X-rays, MRIs (magnetic resonance imagings), EKGs [electrocardiograms), etc.) as these patients visited doctor offices , received hospital-based or home care services, and obtained prescription medications and other therapies. Procedures were in place to ensure the data quality and integrity of these patient files. Going forward, any health care professional across the network could access a patient's complete record, ensuring accurate, timely and comprehensive information sharing about that patient's medical history, allergies, current treatments and other related information. In and of itself, the investment in this electronic medical records (EMR) system was expected to reduce delays in service delivery, mistakes in treating the patient and overall health care costs. When coupled with a computerized patient order entry (CPOE) system to inform Plunkett Research, Lid "U.S. Healthcare Industry Overview 2008 www.plunkettre search.comIndustries/Health Care/tabid/205/Default.aspx. Lucian L. Leape and Donald M. Berwick, "Five Years after to Erris Human: What Have We Learned? Lumal of the American Medical Association. May 18, 2005, pp. 2384-2390. William W. Stead and Herbert S. Lin, editors. Computational Technology for Effective Health Care: Immediate Steps and Strategic Directions, National Academy of Sciences, National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2009. the selection of drugs and appropriate treatment, PHS health care professionals were now positioned to target more specific therapies for their patients, to identify the most effective, low-cost options among potential treatment strategies and to draw on a vast body of experience-based knowledge across the network to inform patient care. BACKGROUND: THE CHALLENGES FACING THE HEALTH CARE INDUSTRY U.S. expenditures on health care in 2008 exceeded $2 trillion. Of that amount, approximately $747 billion was spent on hospital services, $502 billion on physician and clinical services, $199 billion on nursing home and home health care services, and $247 billion on prescription drugs. The cost of health care was expected to spiral even further out of control as the 1950s baby-boomer population became elderly. Alongside the growing furor over escalating costs, the health care industry also faced persistent questions about the quality of the services it provided. Although the quality debate had persisted for some time, recent studies estimated that preventable medical errors led to as many as 98,000 deaths per year in the United States, clearly suggesting that better informed and more knowledgeable health care practices could not only save money for the government, insurance companies and individual-paying patients but could also save lives. In its most recent and comprehensive statement to date on the need to transform health care delivery in the United States through better information management, a study sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences observed: Health care is an information and knowledge-intensive enterprise. In the future, health care providers will need to rely increasingly on information technology (IT) to acquire, manage, analyze, and disseminate health care information and knowledge. Many studies have identified deficiencies in the current health care system, including inadequate care, superfluous or incorrect care, immense inefficiencies and hence high costs, and inequities in access to care. In response, federal policy makers have tended to focus on the creation and interchange of electronic health information and the use of IT as critical infrastructural improvements whose deployments help to address some (but by no means all) of these deficiencies. The authors of this report determined that the crisis in health care delivery was not just a matter of the cost of these services but also a matter of quality. Even within the typical medical practice or hospital, information about the patient was not integrated nor was it effectively leveraged to prescribe cost-effective therapies. Over the last two decades, a growing consensus has emerged that health care institutions fail to deliver the "most [cost] effective care and suffer substantially as a result of medical errors." The National Academy of Sciences study observed that: These persistent problems do not reflect incompetence on the part of health care professionals rather, they are a consequence of the inherent intellectual complexity of health care taken as a whole and a medical care environment that has not been adequately structured to help clinicians avoid mistakes or to systematically improve their decision making and practice. Administrative and organizational fragmentation, together with complex, distributed, and unclear authority and responsibility, further complicates the health care environment." The current state of health care industry performance could be considered from both a cost and quality standpoint, as a consequence of three sets of intersecting factors: 1. First, the nature of health care decisions were fraught with uncertainty about the patient's current state of health and past medical history, the patient's genetic predisposition (or lack thereof) to particular medical therapies and the actual effectiveness of past and future treatments for that particular patient. 2. Second, the economic structure of health care delivery in the United States was extremely complex and could be argued to be counter-intuitive to the encouragement of low-cost options. Instead, the system actively encouraged high-cost procedures under the guise of promoting risk-avoiding, "better" medicine 3. Third and finally, the very information systems and standards that could afford better integrated service delivery, the identification of lower-cost medical options and the avoidance of mistakes in the prescription of medications and other therapies were implemented in such ways as to throw up significant barriers to information sharing and data-driven decision support." Despite the many very real barriers to the improvement of health care services delivery, the U.S. Federal government, health care services organizations, medical practitioners, health insurance companies and information technology companies that serviced this industry were coming together to help address these concerns. This effort required a significant investment of resources over an extended period of time, perhaps a decade or more." Major US research hospitals and their affiliated service delivery arms were transforming health care delivery in ways that could serve as a blueprint for industry-wide change. Among these institutions, Partners Health Care System (PHS) illustrated the potential opportunities and the ongoing challenges in achieving more integrated, higher-quality and less expensive health care services delivery. AN INTRODUCTION TO PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM (PHS) Partners Health Care (PHS) was founded in 1994 by the partnering of Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital to become an integrated health care delivery system that offered patients a continuum of coordinated high-quality care. As of 2009, the system included 6,300 primary care and specialty physicians; 11 hospitals, including its two founding academic medical centers, specialty facilities, community health centers and other health care-related entities, and an ongoing affiliation with Harvard * Wiliam W. Stead and Herbert S. Lin, editors. Computational Technology for Effective Health Care: Immediate Steps and Strategic Directions National Academy of Sciences, National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2009. p. 3 Ibid "Rainu Kaushal et al., "The Costs of a National Health Information Network." Annals of Internal Medicine, August 2, 2005, pp. 165-73 Medical School, In 2008, Partners HealthCare serviced approximately 2.9 million outpatient visits and 149,000 hospital admissions. Its facilities at that time included 3,500 licensed hospital beds, serviced by 40,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees across its network of affiliates. For fiscal year 2008, PHS generated more than $7 billion in revenue and conducted approximately $1 billion worth of biomedical research. PHS also pursued joint ventures with the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology, Dana-Farber, Partners Cancer Care, the Harvard Clinical Research Institute and The Partners Center for Personalized Genetic Medicine (see Exhibit I for an overview of the PHS organization). Over the years, PHS had come to exemplify the large, complex, successful and highly regarded metropolitan health care provider, closely linked with academic medicine and medical research. Its affiliation with Harvard Medical School and its exploration of leading-edge medical practices garnered PHS substantial federal and private medical industry funding to support a rich portfolio of research projects. PHS held information on more than 4.6 million patients, augmenting these records in 2009 through 2.9 million office visits, 149,000 hospital stays and the processing of 20 million prescription drug orders. From its inception, Partners focused both on keeping the costs of its services under control and continuously improving the quality of service delivery and overall patient outcomes. To this end, the organization's leadership extended the electronic medical record integration achieved at both the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital across its entire network. This investment improved the quality of decision making both by individual doctors and medical teams concerning prescription drugs and other medical therapies. It also leveraged medical practice knowledge to improve the preventive and therapeutic treatments that the PHS network offered its patients. These aggressive efforts to improve the quality, safety and efficiency of care were the centerpiece of the so-called "High Performance Medicine Initiative" at PHS, which concluded in 2009. In reviewing the serious and capital- intensive efforts made by PHS on all of these fronts, Dr. James J. Mongan, president and chief executive officer of Partners Health Care observed: Partners HealthCare is playing a leadership role in each area, and in fact, Partners is demonstrating how organized systems can lead to solutions. Only organized systems - as opposed to the very fragmented, disorganized non-systems that make up much of American medicine - only organized systems can implement reimbursement reform, thoroughly disseminate electronic medical records, and establish sophisticated disease management programs. AN INTRODUCTION TO PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM'S INFORMATION SYSTEMS (IS) ORGANIZATION PHS maintained a substantial information management arm. The 2009 Information Systems (IS) team comprised 1,500 employees operating out of 19 locations in the greater Boston metropolitan area. With an operating budget of S196 million in fiscal year 2009 and a capital budget of $68 million, IS supported 80,000 end-users and 82,000 networked computer devices running in 140 PHS locations. In an average month in 2009, the Is organization answered 18,000 calls, and over the course of 2009, it managed 250 major information technology (IT) projects for the enterprise. To realize its information management objectives, PHS had invested heavily in information technology over the years and had hired some of the best information management professionals in the industry. John Glaser, the chief information officer (CIO) at PHS, had served in the same capacity at Brigham and Women's Hospital prior to the establishment of PHS. His first hire was Mary Finlay, who later became his deputy CIO. Together they had served PHS since its inception, focusing on a strategic approach toward IS unit staffing, planning and research, and the deployment of an overall IT architecture across the greater PHS organization of end-users. Key personnel across the IS unit had, in addition to medical credentials, either IT or business management credentials. Among the distinguishing features of the PHS Information Systems organization were the following: Stability in executive management and consistency in the articulation and pursuit of a common strategic vision for the role of IT within PHS. Top-flight talent recruited and retained in key positions across the organization. The placement of executive level (i.e. CIO) positions within major business units to ensure an ongoing C-level presence and thus alignment of IT within the business. The development, adoption and maintenance of an enterprise-level architectural approach to IT selection and acquisition Given the intense and in some ways unique use of IT in the various member hospitals and medical services units of PHS, each major business unit had its own customer-facing CIO, including Partners Community Healthcare, Inc., which supported the 6,000-plus general and specialist physician groups affiliated with PHS's constellation of hospitals. John Glaser's intent was to ensure that each key business unit within PHS had a strong IS advocate to focus on the particular information systems and technology needs of that constituency's health care practitioners (see Exhibit 2 for an overview of the PHS IS organization) . As part of IS' commitment to research and development (R&D), Glaser commissioned organizational units to investigate the IT-enablement of core PHS business processes, including the following: Clinical Informatics Research and Development to address clinical informatics infrastructure The Center for Information Technology Leadership at Partners, which explored the return on investment when purchasing an EMR or other health care information technologies The Center for Connected Health, which considered how developments in IT and telecommunications could transform health care delivery modalities 12B2/National Center for Biomedical Computing, which studied the genetic similarities among cohorts of PHS patients that reflected a paulicula respond to picuild modical dictapics Clinical and Quality Analysis, which explored the impact of the PHS EMR and CPOE systems on care delivery PHS recognized early on that to be successful in these regards, three information management capabilities were required: 1. The mcans to collect and consolidate into an integrated digital record all the information about a given patient over time, including medical data, such as age, weight, height and vital signs; textual information, namely the transcribed comments of those health care professionals with whom the patient had interacted, and objects, such as X-rays and MRI scans, 2. Decision support processes that support the medical practitioner in making the best recommendations for drugs and other therapies on the basis of their likely benefits (1.e. positive outcomes) to the patient at the lowest possible cost. 3. Knowledge management processes that derive best practices from the observable outcomes of recommended medical therapies and employ these lessons learned to inform the ongoing delivery of services and the reform of existing therapies. . PHS's medical and is leadership saw the company's investment in IT as the enabling information system foundation to achieve these capabilities. P