Question: answer question 3 help me if the display assembly team approves and implements the installation jig project. what form of proiect organization would be most

answer question 3 help me if the display assembly team approves and implements the installation jig project. what form of proiect organization would be most appropriate?

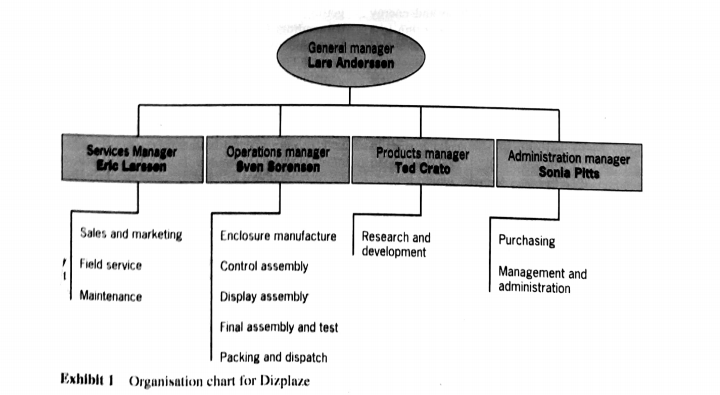

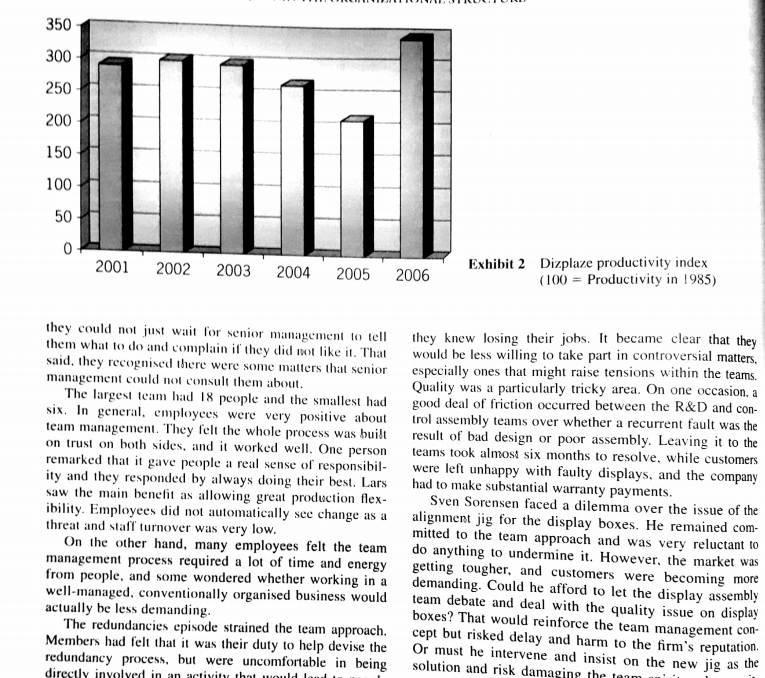

As he drove into the employee car park, Sven Sorensen was once again thinking about how to handle the decision to install a new jig to improve the alignment of the Mark Ten line of display boxes made by the Dizplaze com- pany, where he was the operations manager. The issue had arisen because of a series of complaints by a metro system in Germany. The passenger displays fitted at roof level inside the cars of their new fleet of trains were rattling and working loose from their mountings. These displays were the first Mark Tens to go into service anywhere, and the hope was that this customer would be an important refer- ence. Investigations by the Dizplaze R&D department had identified the cause as poor assembly owing to the com- plex alignment of the display box components. Now the firm was committed to replacing all the defective display boxes. His mind returned to the meeting he had had the pre- vious day with Lars Anderssen, the general manager. They had discussed whether this was an issue where senior management should take the decision to install the jig, or whether it was a matter that needed to be referred to the display assembly team in the factory. As he locked his car in the car park Sven reflected on how slow and difficult it could be to make changes at Dizplaze with its team management philosophy. Dizplaze was founded in Malmo, Sweden, in 1972 by two electrical engineers who saw the opportunity to develop a mobile version of the mechanical dot matrix displays being installed in airports and train stations to provide passenger information. These mobile versions would have to be more robust to cope with the shocks from the movement of buses, trams and trains and they had patented a way to do this. Over the next 10 years the company grew steadily as the benefits of the new tech- nology became accepted, and the reliability of the units improved. They replaced roller blind displays which car- ried route information at the front of road and rail vehi- cles, but which were bulky and unreliable. Several years later, light array systems were intro- duced. These contained small lights which turned on and off to create either static or scrolling messages. Their main application was in passenger information displays fitted inside a vehicle. Despite the market success labour relations within the firm became strained. The founders were outstanding technically, but lacked strong people management skills Their investors persuaded them to employ a general manager, Anders Ekberg. Anders quickly determined that many of the problems Dizplaze faced were because most of the employees did not feel committed to the firm-it was simply a job to them. However, the nature of the display units required a great deal of careful hand assembly to create a high quality product. Following a period of consultation with everyone in the company, Anders introduced a much more participative style of management. The company was split into a number of teams, each entirely respon- sible for its share of the work. There were 11 teams. Five were focussed on production: enclosure manufac- ture, control assembly, display assembly, final assembly and test, and packing and dispatch. The other six were: research and development (R&D), sales and marketing, purchasing, management and administration (including human resources), field service, and maintenance. The teams set their own work schedules, allocated members to tasks, and handled the less serious disciplin ary matters (poor timekeeping, not maintaining a tidy work space, etc.). They met regularly to discuss working issues and ways to be more productive. Only the more complex problems were referred to senior management to be dealt with. Teams were also given a training and development budget. The change was a great success. In fact, the produc tion teams were allowed to insert a small panel inside each completed display unit, signed by the people who had produced it. There were steady productivity improve ments and teams came up with innovations in areas as different as the design of packaging (to reduce damage in transit) and signing in instead of clocking on. Meat while the R&D team were keeping pace with market CASE 211 developments and making sure the products remained competitive. In 2005 the fun LED units were introduced, and they soon became the mainstream product line Overall the firm was going from strength to strength. In 2001 Andern left the businen for a job in the United Staten, and Lars Andersen, the operation manager, was promoted to lead the businen. Sven Sorensen was recruited to fill the role of operation manager. Exhibiti show the company organisation chart in 2009. Lan enthusiastically embraced the team management culture Between 2002 and 2006 Sven recalled a period of rapidly increasing productivity and an expanding labour force Exhibit 2 shows the productivity trend from 2000 10 2006. Unfortunately, trouble was only just round the comer. Although their units were sometimes found in ferries and cruise ships. Divplave's main customers were large bus and train operators, and most units were fitted into band new vehicles. Public transport is an industry subject to lots of external pressures. Publicly owned operators depend on politicians for capital and funding for new equipment may dry up in the face of other prontie's. Private opera tors may delay new orders because interest rates are 100 high or revenue growth has slowed. Onders also tend to be quite large, no missing out on an order can have painful con sequences. In 2007 Dirplaze sullered a series of setbacks. New bus orders were down in key markets, and only one major train contract was out for tender that they could bid on. They did not win the train contract, which meant that revenues would be at least 20% down on the previous year. Lars commitment to the all of Dizplave was that long term employment was a basic goal in return for their com- mitment, and that he would do everything possible to avoid redundancies. A hiring freeze was put in place, and despite the reduced workload no one was laid off. Lars expected that new orders would fill the gap left by the lost train business. Several small orders came in, but not enough to cover the costs of the workforce. In February 2008, Lars announced that redundancies would be necessary. The leams were not expected to decide who would have to leave, but they were consulted on the factors that would be used to make the tough decisions. They agreed that factors such as length of service, level of relevant skills and disci- plinary record should be taken into account. Even though the process was painful, almost everyone (even among those who lost their jobs) thought it was fair The consequence of the lay-offs was increased pro- ductivity and reduced costs. This made Dizplave more competitive and the order book started to fill up again. From then on, temporary staff tended to be brought in to help with peaks in demand, along with more overtime for the full-time employees. The team concept had been in place for about 20 years and had naturally evolved over that time. The format of team meetings had a common pattern and the team lead- ers were rotated every six months. Teams met in work time once a week for about an hour and a half. Discus- sions could drag on sometimes, but the advantage was that once a decision was taken it could be implemented immediately. Temporary workers could attend meetings but were not allowed to vote. There was no doubt that most of the teams were well aware of the reality of the external market when making their decisions. They knew General manager Lars Andersson Services Manager Eric Larsson Operations manager Sven Sorenson Products manager Tod Crato Administration manager Sonia Pitts Research and development Purchasing Management and administration Sales and marketing Enclosure manufacture Field Service Control assembly Maintenance Display assembly Final assembly and test Packing and dispatch Exhibit Organisation chart for Dizplaze 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Exhibit 2 Dizplaze productivity index (100 = Productivity in 1985) they could not just wait for senior management to tell them what to do and complain if they did not like it. That said, they recognised there were some matters that senior management could not consult them about. The largest team had 18 people and the smallest had six. In general, employees were very positive about team management. They felt the whole process was built on trust on both sides, and it worked well. One person remarked that it gave people a real sense of responsibil- ity and they responded by always doing their best. Lars saw the main benefit as allowing great production flex- ibility. Employees did not automatically see change as a threat and staff turnover was very low. On the other hand, many employees felt the team management process required a lot of time and energy from people, and some wondered whether working in a well-managed, conventionally organised business would actually be less demanding. The redundancies episode strained the team approach. Members had felt that it was their duty to help devise the redundancy process, but were uncomfortable in being directly inyolyed in an activity that would they knew losing their jobs. It became clear that they would be less willing to take part in controversial matters, especially ones that might raise tensions within the teams. Quality was a particularly tricky area. On one occasion, a good deal of friction occurred between the R&D and con- trol assembly teams over whether a recurrent fault was the result of bad design or poor assembly. Leaving it to the teams took almost six months to resolve, while customers were left unhappy with faulty displays, and the company had to make substantial warranty payments. Sven Sorensen faced a dilemma over the issue of the alignment jig for the display boxes. He remained com- mitted to the team approach and was very reluctant to do anything to undermine it. However, the market was getting tougher, and customers were becoming more demanding. Could he afford to let the display assembly team debate and deal with the quality issue on display boxes? That would reinforce the team management con- cept but risked delay and harm to the firm's reputation. Or must he intervene and insist on the new jig as the solution and risk damagine the team six. In general, employees were very positive about team management. They felt the whole process was built on trust on both sides, and it worked well. One person remarked that it gave people a real sense of responsibil- ity and they responded by always doing their best. Lars saw the main benefit as allowing great production flex- ibility. Employees did not automatically see change as a threat and staff turnover was very low. On the other hand, many employees felt the team management process required a lot of time and energy from people, and some wondered whether working in a well-managed, conventionally organised business would actually be less demanding. The redundancies episode strained the team approach. Members had felt that it was their duty to help devise the redundancy process, but were uncomfortable in being directly involved in an activity that would lead to people good deal of friction occurred between the R&D and con- trol assembly teams over whether a recurrent fault was the result of bad design or poor assembly. Leaving it to the teams took almost six months to resolve, while customers were left unhappy with faulty displays, and the company had to make substantial warranty payments. Sven Sorensen faced a dilemma over the issue of the alignment jig for the display boxes. He remained com- mitted to the team approach and was very reluctant to do anything to undermine it. However, the market was getting tougher, and customers were becoming more demanding. Could he afford to let the display assembly team debate and deal with the quality issue on display boxes? That would reinforce the team management con- cept but risked delay and harm to the firm's reputation. Or must he intervene and insist on the new jig as the solution and risk damaging the team spirit and commit- ment everyone had worked so hard to nurture? QUESTIONS 1. Jf Sven decides to go ahead and install the alignment jig without discussing it with the display assembly team, what are the potential conflicts that might arise? What are the advantages of doing this anyway? 2. If Sven decides to allow the display assembly team to make the decision, what are the potential problems? What would be the advantages? 3. If the display assembly team approves and implements the installation jig project, what form of project organi- zation would be most appropriate? 4. Given the size of this organization and be number of projects they deal with, would it make sense to institute a Project Management Office? Is there another arrangement that might be a better alternative? irStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts