Question: Answer the following questions 1 Identify the goal(s)/problem(s) 2 Generate, analyze and evaluate the solution 3 Recommend preferred/optimal solution and create an action plan 4

Answer the following questions

1 Identify the goal(s)/problem(s)

2 Generate, analyze and evaluate the solution

3 Recommend preferred/optimal solution and create an action plan

4 As the owner of Turner-Plask Potatoes, what would you do? Be sure to consider

the implications to your company.

5 As the owner of Uli Importers, what would you do? Be sure to consider the

implications to your company.

6 As a decision-maker at Buwing Canada, would you treat Turner-Plask Potatoes

and Uli Importers differently because of their situation? What else would you

recommend for Buwing Canada to have responsible supplier relationships?

Answer each question in 20-25 lines

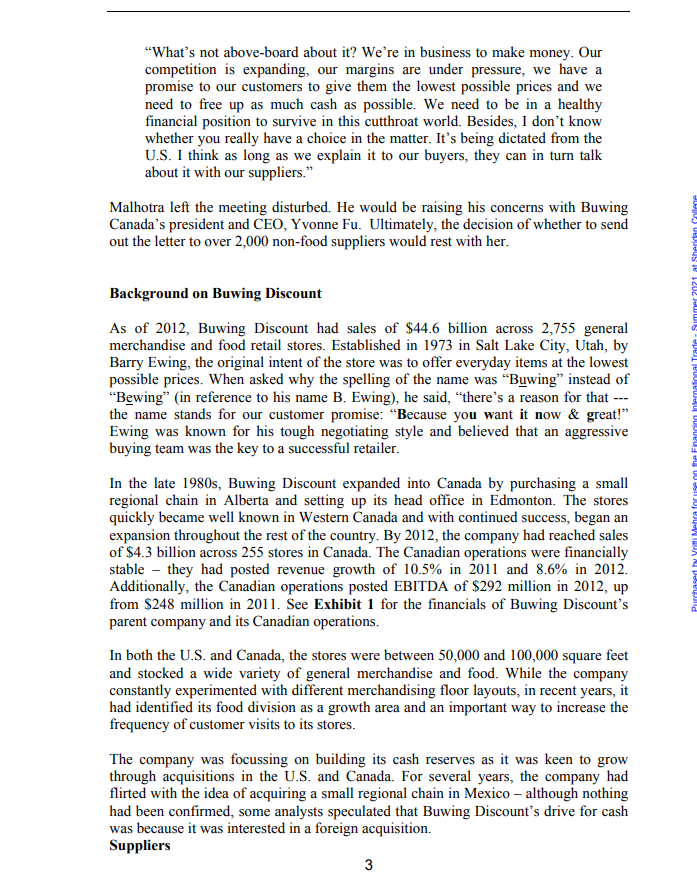

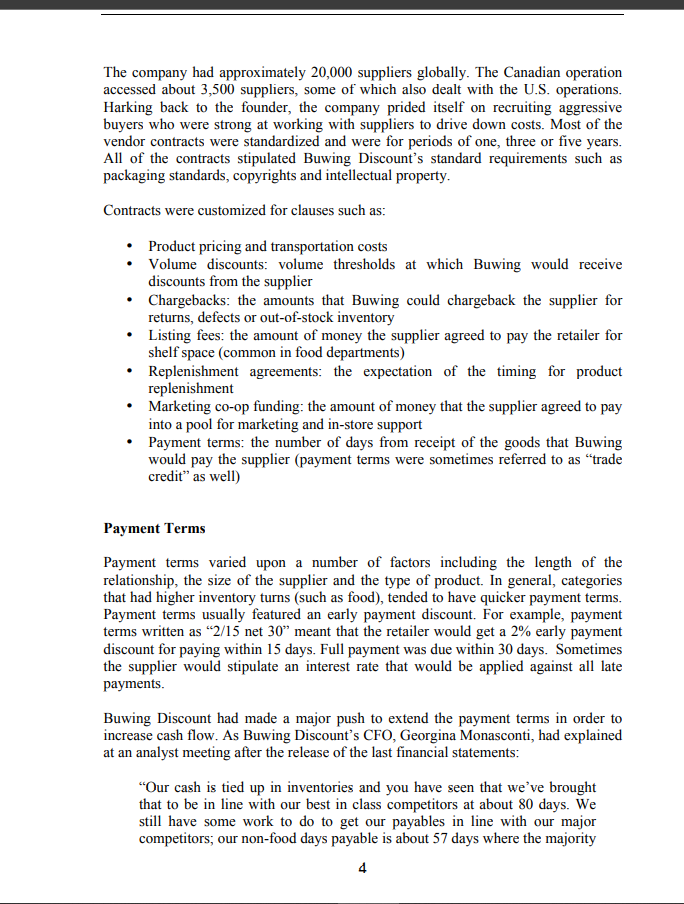

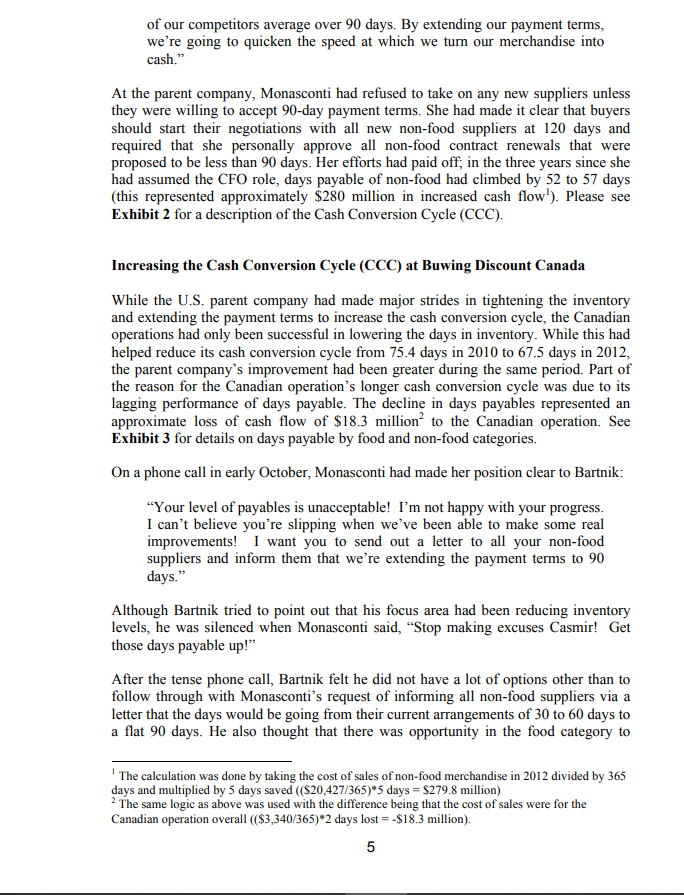

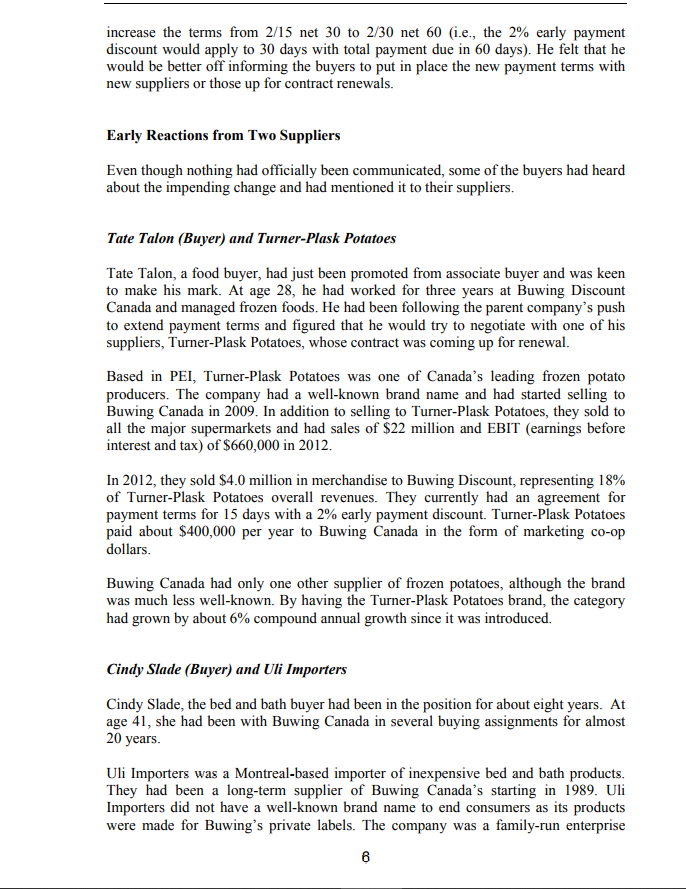

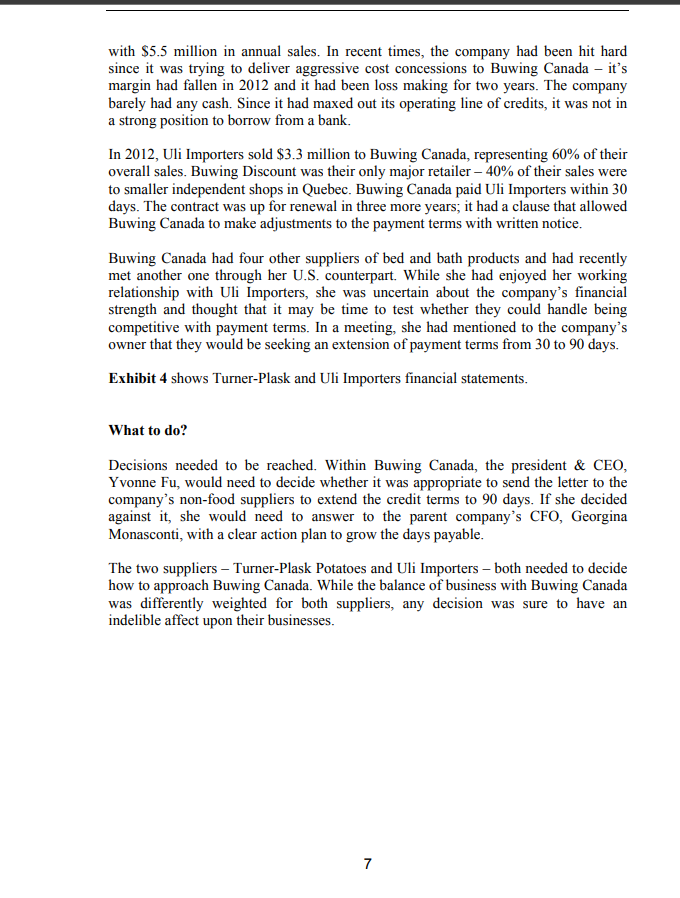

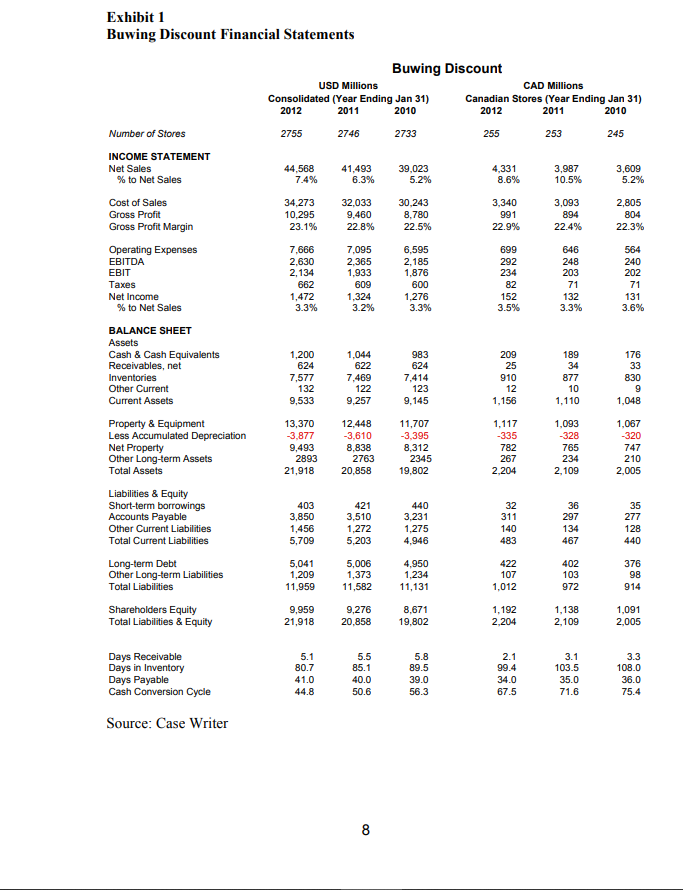

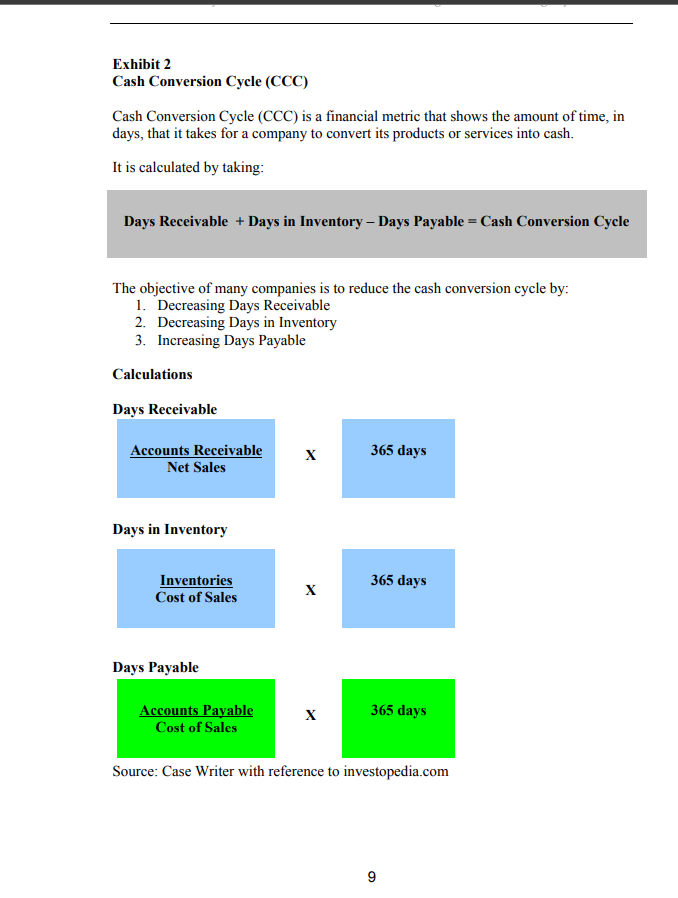

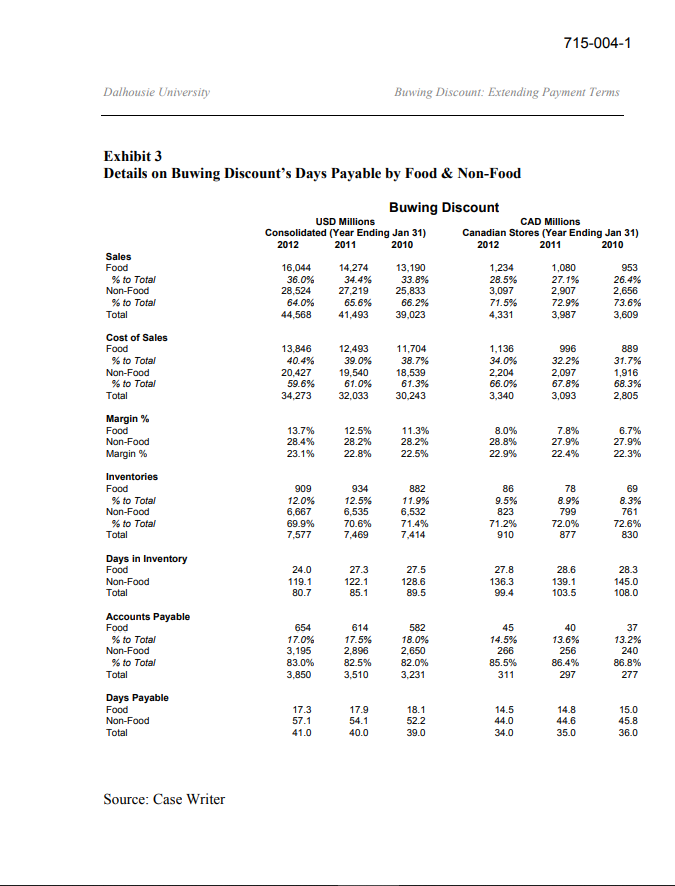

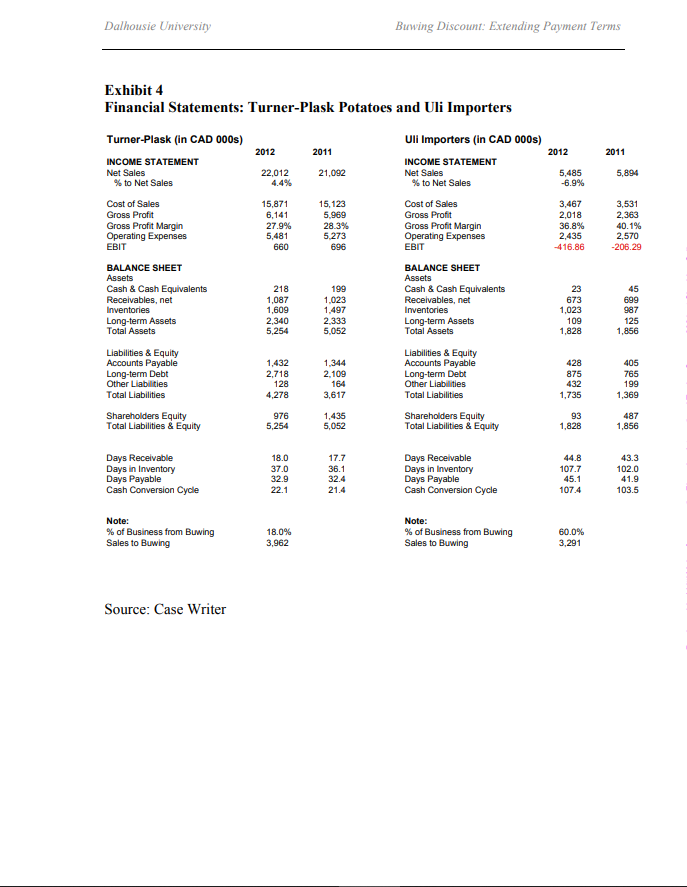

Buwing Discount: Extending Payment Terms Introduction In late October 2012, as the end of the third quarter was drawing near, Buwing Canada's VP of Finance, Casmir Bartnik, said to Aryan Malhotra, VP of Merchandising: Aryan, I'm under a lot of pressure from Georgina Monasconti, the CFO at our parent company to extend the payment terms to our suppliers. Even though we're profitable, she's not happy with our cash conversion cycle and wants me to get a lot more aggressive with increasing our cash flow by pushing out the days payable. Right now, we're at 34 days when the parent company is at 41 days. So, I'm going to send a letter that will go out to all of our non-food suppliers to take the terms to 90 days. The majority are currently between 30 and 60 days. As for our food suppliers, I think the best way is to get our internal buyers to renegotiate when the contracts come up for renewal. Malhotra responded: Cas, I think we're taking a massive risk here. Has legal looked at this? I know our standard contract gives us the ability to adjust terms, but a lot of the suppliers will be up in arms if we send out a letter without any warning. Furthermore, I've spoken with our buyers and suppliers about being fully transparent in our dealings. I don't think this is 100% above-board. Also, a lot of suppliers won't have the financial wherewithal to deal with their receivables growing." This case was written by Jordan Mitchell to provide discussion only. Some information has been disguised to protect confidentiality. It is not the intention of the author to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of the situation or to comment on any prevailing laws, government policy or company and industry practices. The author would like to acknowledge Peggy Cunningham, Christine Dimitrov and Samantha Begelfor in the development of this case. Version Date: November 3, 2012. What's not above-board about it? We're in business to make money. Our competition is expanding, our margins are under pressure, we have a promise to our customers to give them the lowest possible prices and we need to free up as much cash as possible. We need to be in a healthy financial position to survive in this cutthroat world. Besides, I don't know whether you really have a choice in the matter. It's being dictated from the U.S. I think as long as we explain it to our buyers, they can in turn talk about it with our suppliers." Malhotra left the meeting disturbed. He would be raising his concerns with Buwing Canada's president and CEO, Yvonne Fu. Ultimately, the decision of whether to send out the letter to over 2,000 non-food suppliers would rest with her. Background on Buwing Discount As of 2012, Buwing Discount had sales of $44.6 billion across 2,755 general merchandise and food retail stores. Established in 1973 in Salt Lake City, Utah, by Barry Ewing, the original intent of the store was to offer everyday items at the lowest possible prices. When asked why the spelling of the name was "Buwing" instead of "Bewing (in reference to his name B. Ewing), he said, "there's a reason for that --- the name stands for our customer promise: Because you want it now & great!" Ewing was known for his tough negotiating style and believed that an aggressive buying team was the key to a successful retailer. the Financing International Trade Summer 2021 at Sheridan folle In the late 1980s, Buwing Discount expanded into Canada by purchasing a small regional chain in Alberta and setting up its head office in Edmonton. The stores quickly became well known in Western Canada and with continued success, began an expansion throughout the rest of the country. By 2012, the company had reached sales of $4.3 billion across 255 stores in Canada. The Canadian operations were financially stable - they had posted revenue growth of 10.5% in 2011 and 8.6% in 2012. Additionally, the Canadian operations posted EBITDA of $292 million in 2012, up from $248 million in 2011. See Exhibit 1 for the financials of Buwing Discount's parent company and its Canadian operations. Purchased by Yritti Mehra for 119 In both the U.S. and Canada, the stores were between 50,000 and 100,000 square feet and stocked a wide variety of general merchandise and food. While the company constantly experimented with different merchandising floor layouts, in recent years, it had identified its food division as a growth area and an important way to increase the frequency of customer visits to its stores. The company was focussing on building its cash reserves as it was keen to grow through acquisitions in the U.S. and Canada. For several years, the company had flirted with the idea of acquiring a small regional chain in Mexico - although nothing had been confirmed, some analysts speculated that Buwing Discount's drive for cash was because it was interested in a foreign acquisition. Suppliers 3 The company had approximately 20,000 suppliers globally. The Canadian operation accessed about 3,500 suppliers, some of which also dealt with the U.S. operations. Harking back to the founder, the company prided itself on recruiting aggressive buyers who were strong at working with suppliers to drive down costs. Most of the vendor contracts were standardized and were for periods of one, three or five years. All of the contracts stipulated Buwing Discount's standard requirements such as packaging standards, copyrights and intellectual property. Contracts were customized for clauses such as: Product pricing and transportation costs Volume discounts: volume thresholds at which Buwing would receive discounts from the supplier Chargebacks: the amounts that Buwing could chargeback the supplier for returns, defects or out-of-stock inventory Listing fees: the amount of money the supplier agreed to pay the retailer for shelf space (common in food departments) Replenishment agreements: the expectation of the timing for product replenishment Marketing co-op funding: the amount of money that the supplier agreed to pay into a pool for marketing and in-store support Payment terms: the number of days from receipt of the goods that Buwing would pay the supplier (payment terms were sometimes referred to as "trade credit as well) Payment Terms Payment terms varied upon a number of factors including the length of the relationship, the size of the supplier and the type of product. In general, categories that had higher inventory turns (such as food), tended to have quicker payment terms. Payment terms usually featured an early payment discount. For example, payment terms written as "2/15 net 30 meant that the retailer would get a 2% early payment discount for paying within 15 days. Full payment was due within 30 days. Sometimes the supplier would stipulate an interest rate that would be applied against all late payments. Buwing Discount had made a major push to extend the payment terms in order to increase cash flow. As Buwing Discount's CFO, Georgina Monasconti, had explained at an analyst meeting after the release of the last financial statements: Our cash is tied up in inventories and you have seen that we've brought that to be in line with our best in class competitors at about 80 days. We still have some work to do to get our payables in line with our major competitors; our non-food days payable is about 57 days where the majority 4 of our competitors average over 90 days. By extending our payment terms, we're going to quicken the speed at which we turn our merchandise into cash." At the parent company, Monasconti had refused to take on any new suppliers unless they were willing to accept 90-day payment terms. She had made it clear that buyers should start their negotiations with all new non-food suppliers at 120 days and required that she personally approve all non-food contract renewals that were proposed to be less than 90 days. Her efforts had paid off, in the three years since she had assumed the CFO role, days payable of non-food had climbed by 52 to 57 days (this represented approximately $280 million in increased cash flow!). Please see Exhibit 2 for a description of the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC). Increasing the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) at Buwing Discount Canada While the U.S. parent company had made major strides in tightening the inventory and extending the payment terms to increase the cash conversion cycle, the Canadian operations had only been successful in lowering the days in inventory. While this had helped reduce its cash conversion cycle from 75.4 days in 2010 to 67.5 days in 2012, the parent company's improvement had been greater during the same period. Part of the reason for the Canadian operation's longer cash conversion cycle was due to its lagging performance of days payable. The decline in days payables represented an approximate loss of cash flow of $18.3 million to the Canadian operation. See Exhibit 3 for details on days payable by food and non-food categories. On a phone call in early October, Monasconti had made her position clear to Bartnik: Your level of payables is unacceptable! I'm not happy with your progress. I can't believe you're slipping when we've been able to make some real improvements! I want you to send out a letter to all your non-food suppliers and inform them that we're extending the payment terms to 90 days." Although Bartnik tried to point out that his focus area had been reducing inventory levels, he was silenced when Monasconti said, Stop making excuses Casmir! Get those days payable up!" After the tense phone call, Bartnik felt he did not have a lot of options other than to follow through with Monasconti's request of informing all non-food suppliers via a letter that the days would be going from their current arrangements of 30 to 60 days to a flat 90 days. He also thought that there was opportunity in the food category to The calculation was done by taking the cost of sales of non-food merchandise in 2012 divided by 365 days and multiplied by 5 days saved ((S20,427/365)*5 days = $279.8 million) 2 The same logic as above was used with the difference being that the cost of sales were for the Canadian operation overall (($3,340/365)*2 days lost = -$18.3 million). 5 increase the terms from 2/15 net 30 to 2/30 net 60 (i.e., the 2% early payment discount would apply to 30 days with total payment due in 60 days). He felt that he would be better off informing the buyers to put in place the new payment terms with new suppliers or those up for contract renewals. Early Reactions from Two Suppliers Even though nothing had officially been communicated, some of the buyers had heard about the impending change and had mentioned it to their suppliers. Tate Talon (Buyer) and Turner-Plask Potatoes Tate Talon, a food buyer, had just been promoted from associate buyer and was keen to make his mark. At age 28, he had worked for three years at Buwing Discount Canada and managed frozen foods. He had been following the parent company's push to extend payment terms and figured that he would try to negotiate with one of his suppliers, Turner-Plask Potatoes, whose contract was coming up for renewal. Based in PEI, Turner-Plask Potatoes was one of Canada's leading frozen potato producers. The company had a well-known brand name and had started selling to Buwing Canada in 2009. In addition to selling to Turner-Plask Potatoes, they sold to all the major supermarkets and had sales of $22 million and EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) of $660,000 in 2012. In 2012, they sold $4.0 million in merchandise to Buwing Discount, representing 18% of Turner-Plask Potatoes overall revenues. They currently had an agreement for payment terms for 15 days with a 2% early payment discount. Turner-Plask Potatoes paid about $400,000 per year to Buwing Canada in the form of marketing co-op dollars. Buwing Canada had only one other supplier of frozen potatoes, although the brand was much less well-known. By having the Turner-Plask Potatoes brand, the category had grown by about 6% compound annual growth since it was introduced. Cindy Slade (Buyer) and Uli Importers Cindy Slade, the bed and bath buyer had been in the position for about eight years. At age 41, she had been with Buwing Canada in several buying assignments for almost 20 years. Uli Importers was a Montreal-based importer of inexpensive bed and bath products. They had been a long-term supplier of Buwing Canada's starting in 1989. Uli Importers did not have a well-known brand name to end consumers as its products were made for Buwing's private labels. The company was a family-run enterprise 6 with $5.5 million in annual sales. In recent times, the company had been hit hard since it was trying to deliver aggressive cost concessions to Buwing Canada - it's margin had fallen in 2012 and it had been loss making for two years. The company barely had any cash. Since it had maxed out its operating line of credits, it was not in a strong position to borrow from a bank. In 2012, Uli Importers sold $3.3 million to Buwing Canada, representing 60% of their overall sales. Buwing Discount was their only major retailer - 40% of their sales were to smaller independent shops in Quebec. Buwing Canada paid Uli Importers within 30 days. The contract was up for renewal in three more years, it had a clause that allowed Buwing Canada to make adjustments to the payment terms with written notice. Buwing Canada had four other suppliers of bed and bath products and had recently met another one through her U.S. counterpart. While she had enjoyed her working relationship with Uli Importers, she was uncertain about the company's financial strength and thought that it may be time to test whether they could handle being competitive with payment terms. In a meeting, she had mentioned to the company's owner that they would be seeking an extension of payment terms from 30 to 90 days. Exhibit 4 shows Turner-Plask and Uli Importers financial statements. What to do? Decisions needed to be reached. Within Buwing Canada, the president & CEO, Yvonne Fu, would need to decide whether it was appropriate to send the letter to the company's non-food suppliers to extend the credit terms to 90 days. If she decided against it, she would need to answer to the parent company's CFO, Georgina Monasconti, with a clear action plan to grow the days payable. The two suppliers Turner-Plask Potatoes and Uli Importers - both needed to decide how to approach Buwing Canada. While the balance of business with Buwing Canada was differently weighted for both suppliers, any decision was sure to have an indelible affect upon their businesses. 7 Exhibit 1 Buwing Discount Financial Statements Buwing Discount USD Millions CAD Millions Consolidated (Year Ending Jan 31) 2012 2011 2010 Canadian Stores (Year Ending Jan 31) 2012 2011 2010 Number of Stores 2755 2746 2733 255 253 245 INCOME STATEMENT 3,609 Net Sales % to Net Sales 44,568 7.4% 41,493 6.3% 39,023 5.2% 4,331 8.6% 3.987 10.5% 5.2% Cost of Sales 34,273 10,295 23.1% 32,033 9,460 22.8% 30,243 8.780 22.5% 3,340 991 Gross Profit Gross Profit Margin 3,093 894 2,805 804 22.9% 22.4% 22.3% 699 564 Operating Expenses EBITDA EBIT 7,666 2,630 2,134 662 292 234 240 202 7,095 2.365 1,933 609 1,324 3.2% 6,595 2,185 1,876 600 1,276 3.3% 646 248 203 71 132 3.3% Taxes 82 71 Net Income % to Net Sales 1,472 3.3% 152 3.5% 131 3.6% BALANCE SHEET Assets Cash & Cash Equivalents Receivables, net 983 624 189 34 176 33 Inventories Other Current 1,200 624 7,577 132 9,533 1,044 622 7.469 122 9,257 7,414 123 209 25 910 12 1,156 877 10 830 9 Current Assets 9.145 1,110 1,048 1.117 -335 1,067 -320 Property & Equipment Less Accumulated Depreciation Net Property Other Long-term Assets Total Assets 13,370 3,877 9,493 2893 21,918 12.448 -3,610 8,838 2763 20,858 11,707 -3,395 8,312 2345 19.802 782 267 1,093 -328 765 234 2,109 747 210 2,204 2.005 Liabilities & Equity Short-term borrowings Accounts Payable Other Current Liabilities Total Current Liabilities 36 297 403 3,850 1.456 5,709 421 3,510 1,272 5,203 440 3,231 1,275 4,946 32 311 140 483 35 277 128 134 467 440 Long-term Debt Other Long-term Liabilities Total Liabilities 5,041 1,209 11,959 5,006 1,373 11,582 4,950 1.234 422 107 402 103 376 98 11,131 1,012 972 914 Shareholders Equity Total Liabilities & Equity 9,959 21,918 9,276 20.858 8,671 19.802 1,192 2.204 1,138 2,109 1,091 2,005 5.1 80.7 5.5 85.1 5.8 89.5 2.1 99.4 3.1 103.5 3.3 108.0 Days Receivable Days in Inventory Days Payable Cash Conversion Cycle 41.0 40.0 39.0 34.0 35.0 36.0 44.8 50.6 56.3 67.5 71.6 75.4 Source: Case Writer 8 Exhibit 2 Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) is a financial metric that shows the amount of time, in days, that it takes for a company to convert its products or services into cash. It is calculated by taking: Days Receivable + Days in Inventory Days Payable = Cash Conversion Cycle The objective of many companies is to reduce the cash conversion cycle by: 1. Decreasing Days Receivable 2. Decreasing Days in Inventory 3. Increasing Days Payable Calculations Days Receivable Accounts Receivable 365 days Net Sales Days in Inventory 365 days Inventories Cost of Sales X Days Payable Accounts Payable Cost of Sales x 365 days Source: Case Writer with reference to investopedia.com 9 Dalhousie University Buwing Discount: Extending Payment Terms Exhibit 4 Financial Statements: Turner-Plask Potatoes and Uli Importers Turner-Plask (in CAD 000s) Uli Importers (in CAD 000s) 2012 2011 2012 2011 INCOME STATEMENT 22.012 21,092 INCOME STATEMENT Net Sales % to Net Sales Net Sales % to Net Sales 5,894 5,485 -6.9% Cost of Sales Gross Profit Gross Profit Margin Operating Expenses EBIT 15,871 6,141 27.9% 5,481 660 15,123 5.969 28.3% 5.273 696 Cost of Sales Gross Profit Gross Profit Margin Operating Expenses EBIT 3,467 2,018 36.8% 2,435 -416.86 3,531 2,363 40.1% 2,570 -206.29 BALANCE SHEET Assets Cash & Cash Equivalents Receivables, net Inventories Long-term Assets Total Assets 218 1,087 1,609 2.340 5,254 199 1.023 1.497 2.333 5,052 BALANCE SHEET Assets Cash & Cash Equivalents Receivables, net Inventories Long-term Assets Total Assets 23 673 1,023 109 45 699 987 125 1,856 1,828 Liabilities & Equity Accounts Payable Long-term Debt Other Liabilities Total Liabilities 1,432 2,718 128 4,278 1,344 2,109 164 3,617 Liabilities & Equity Accounts Payable Long-term Debt Other Liabilities Total Liabilities 428 875 432 1,735 405 765 199 1,369 Shareholders Equity Total Liabilities & Equity 976 5,254 1,435 5,052 Shareholders Equity Total Liabilities & Equity 93 1,828 487 1,856 17.7 36.1 Days Receivable Days in Inventory Days Payable Cash Conversion Cycle 18.0 37.0 32.9 22.1 Days Receivable Days in Inventory Days Payable Cash Conversion Cycle 32.4 21.4 44.8 107.7 45.1 107.4 43.3 102.0 41.9 103.5 Note: Note: % of Business from Buwing 18.0% 3.962 % of Business from Buwing Sales to Buwing 60.0% 3,291 Sales to Buwing Source: Case Writer Buwing Discount: Extending Payment Terms Introduction In late October 2012, as the end of the third quarter was drawing near, Buwing Canada's VP of Finance, Casmir Bartnik, said to Aryan Malhotra, VP of Merchandising: Aryan, I'm under a lot of pressure from Georgina Monasconti, the CFO at our parent company to extend the payment terms to our suppliers. Even though we're profitable, she's not happy with our cash conversion cycle and wants me to get a lot more aggressive with increasing our cash flow by pushing out the days payable. Right now, we're at 34 days when the parent company is at 41 days. So, I'm going to send a letter that will go out to all of our non-food suppliers to take the terms to 90 days. The majority are currently between 30 and 60 days. As for our food suppliers, I think the best way is to get our internal buyers to renegotiate when the contracts come up for renewal. Malhotra responded: Cas, I think we're taking a massive risk here. Has legal looked at this? I know our standard contract gives us the ability to adjust terms, but a lot of the suppliers will be up in arms if we send out a letter without any warning. Furthermore, I've spoken with our buyers and suppliers about being fully transparent in our dealings. I don't think this is 100% above-board. Also, a lot of suppliers won't have the financial wherewithal to deal with their receivables growing." This case was written by Jordan Mitchell to provide discussion only. Some information has been disguised to protect confidentiality. It is not the intention of the author to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of the situation or to comment on any prevailing laws, government policy or company and industry practices. The author would like to acknowledge Peggy Cunningham, Christine Dimitrov and Samantha Begelfor in the development of this case. Version Date: November 3, 2012. What's not above-board about it? We're in business to make money. Our competition is expanding, our margins are under pressure, we have a promise to our customers to give them the lowest possible prices and we need to free up as much cash as possible. We need to be in a healthy financial position to survive in this cutthroat world. Besides, I don't know whether you really have a choice in the matter. It's being dictated from the U.S. I think as long as we explain it to our buyers, they can in turn talk about it with our suppliers." Malhotra left the meeting disturbed. He would be raising his concerns with Buwing Canada's president and CEO, Yvonne Fu. Ultimately, the decision of whether to send out the letter to over 2,000 non-food suppliers would rest with her. Background on Buwing Discount As of 2012, Buwing Discount had sales of $44.6 billion across 2,755 general merchandise and food retail stores. Established in 1973 in Salt Lake City, Utah, by Barry Ewing, the original intent of the store was to offer everyday items at the lowest possible prices. When asked why the spelling of the name was "Buwing" instead of "Bewing (in reference to his name B. Ewing), he said, "there's a reason for that --- the name stands for our customer promise: Because you want it now & great!" Ewing was known for his tough negotiating style and believed that an aggressive buying team was the key to a successful retailer. the Financing International Trade Summer 2021 at Sheridan folle In the late 1980s, Buwing Discount expanded into Canada by purchasing a small regional chain in Alberta and setting up its head office in Edmonton. The stores quickly became well known in Western Canada and with continued success, began an expansion throughout the rest of the country. By 2012, the company had reached sales of $4.3 billion across 255 stores in Canada. The Canadian operations were financially stable - they had posted revenue growth of 10.5% in 2011 and 8.6% in 2012. Additionally, the Canadian operations posted EBITDA of $292 million in 2012, up from $248 million in 2011. See Exhibit 1 for the financials of Buwing Discount's parent company and its Canadian operations. Purchased by Yritti Mehra for 119 In both the U.S. and Canada, the stores were between 50,000 and 100,000 square feet and stocked a wide variety of general merchandise and food. While the company constantly experimented with different merchandising floor layouts, in recent years, it had identified its food division as a growth area and an important way to increase the frequency of customer visits to its stores. The company was focussing on building its cash reserves as it was keen to grow through acquisitions in the U.S. and Canada. For several years, the company had flirted with the idea of acquiring a small regional chain in Mexico - although nothing had been confirmed, some analysts speculated that Buwing Discount's drive for cash was because it was interested in a foreign acquisition. Suppliers 3 The company had approximately 20,000 suppliers globally. The Canadian operation accessed about 3,500 suppliers, some of which also dealt with the U.S. operations. Harking back to the founder, the company prided itself on recruiting aggressive buyers who were strong at working with suppliers to drive down costs. Most of the vendor contracts were standardized and were for periods of one, three or five years. All of the contracts stipulated Buwing Discount's standard requirements such as packaging standards, copyrights and intellectual property. Contracts were customized for clauses such as: Product pricing and transportation costs Volume discounts: volume thresholds at which Buwing would receive discounts from the supplier Chargebacks: the amounts that Buwing could chargeback the supplier for returns, defects or out-of-stock inventory Listing fees: the amount of money the supplier agreed to pay the retailer for shelf space (common in food departments) Replenishment agreements: the expectation of the timing for product replenishment Marketing co-op funding: the amount of money that the supplier agreed to pay into a pool for marketing and in-store support Payment terms: the number of days from receipt of the goods that Buwing would pay the supplier (payment terms were sometimes referred to as "trade credit as well) Payment Terms Payment terms varied upon a number of factors including the length of the relationship, the size of the supplier and the type of product. In general, categories that had higher inventory turns (such as food), tended to have quicker payment terms. Payment terms usually featured an early payment discount. For example, payment terms written as "2/15 net 30 meant that the retailer would get a 2% early payment discount for paying within 15 days. Full payment was due within 30 days. Sometimes the supplier would stipulate an interest rate that would be applied against all late payments. Buwing Discount had made a major push to extend the payment terms in order to increase cash flow. As Buwing Discount's CFO, Georgina Monasconti, had explained at an analyst meeting after the release of the last financial statements: Our cash is tied up in inventories and you have seen that we've brought that to be in line with our best in class competitors at about 80 days. We still have some work to do to get our payables in line with our major competitors; our non-food days payable is about 57 days where the majority 4 of our competitors average over 90 days. By extending our payment terms, we're going to quicken the speed at which we turn our merchandise into cash." At the parent company, Monasconti had refused to take on any new suppliers unless they were willing to accept 90-day payment terms. She had made it clear that buyers should start their negotiations with all new non-food suppliers at 120 days and required that she personally approve all non-food contract renewals that were proposed to be less than 90 days. Her efforts had paid off, in the three years since she had assumed the CFO role, days payable of non-food had climbed by 52 to 57 days (this represented approximately $280 million in increased cash flow!). Please see Exhibit 2 for a description of the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC). Increasing the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) at Buwing Discount Canada While the U.S. parent company had made major strides in tightening the inventory and extending the payment terms to increase the cash conversion cycle, the Canadian operations had only been successful in lowering the days in inventory. While this had helped reduce its cash conversion cycle from 75.4 days in 2010 to 67.5 days in 2012, the parent company's improvement had been greater during the same period. Part of the reason for the Canadian operation's longer cash conversion cycle was due to its lagging performance of days payable. The decline in days payables represented an approximate loss of cash flow of $18.3 million to the Canadian operation. See Exhibit 3 for details on days payable by food and non-food categories. On a phone call in early October, Monasconti had made her position clear to Bartnik: Your level of payables is unacceptable! I'm not happy with your progress. I can't believe you're slipping when we've been able to make some real improvements! I want you to send out a letter to all your non-food suppliers and inform them that we're extending the payment terms to 90 days." Although Bartnik tried to point out that his focus area had been reducing inventory levels, he was silenced when Monasconti said, Stop making excuses Casmir! Get those days payable up!" After the tense phone call, Bartnik felt he did not have a lot of options other than to follow through with Monasconti's request of informing all non-food suppliers via a letter that the days would be going from their current arrangements of 30 to 60 days to a flat 90 days. He also thought that there was opportunity in the food category to The calculation was done by taking the cost of sales of non-food merchandise in 2012 divided by 365 days and multiplied by 5 days saved ((S20,427/365)*5 days = $279.8 million) 2 The same logic as above was used with the difference being that the cost of sales were for the Canadian operation overall (($3,340/365)*2 days lost = -$18.3 million). 5 increase the terms from 2/15 net 30 to 2/30 net 60 (i.e., the 2% early payment discount would apply to 30 days with total payment due in 60 days). He felt that he would be better off informing the buyers to put in place the new payment terms with new suppliers or those up for contract renewals. Early Reactions from Two Suppliers Even though nothing had officially been communicated, some of the buyers had heard about the impending change and had mentioned it to their suppliers. Tate Talon (Buyer) and Turner-Plask Potatoes Tate Talon, a food buyer, had just been promoted from associate buyer and was keen to make his mark. At age 28, he had worked for three years at Buwing Discount Canada and managed frozen foods. He had been following the parent company's push to extend payment terms and figured that he would try to negotiate with one of his suppliers, Turner-Plask Potatoes, whose contract was coming up for renewal. Based in PEI, Turner-Plask Potatoes was one of Canada's leading frozen potato producers. The company had a well-known brand name and had started selling to Buwing Canada in 2009. In addition to selling to Turner-Plask Potatoes, they sold to all the major supermarkets and had sales of $22 million and EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) of $660,000 in 2012. In 2012, they sold $4.0 million in merchandise to Buwing Discount, representing 18% of Turner-Plask Potatoes overall revenues. They currently had an agreement for payment terms for 15 days with a 2% early payment discount. Turner-Plask Potatoes paid about $400,000 per year to Buwing Canada in the form of marketing co-op dollars. Buwing Canada had only one other supplier of frozen potatoes, although the brand was much less well-known. By having the Turner-Plask Potatoes brand, the category had grown by about 6% compound annual growth since it was introduced. Cindy Slade (Buyer) and Uli Importers Cindy Slade, the bed and bath buyer had been in the position for about eight years. At age 41, she had been with Buwing Canada in several buying assignments for almost 20 years. Uli Importers was a Montreal-based importer of inexpensive bed and bath products. They had been a long-term supplier of Buwing Canada's starting in 1989. Uli Importers did not have a well-known brand name to end consumers as its products were made for Buwing's private labels. The company was a family-run enterprise 6 with $5.5 million in annual sales. In recent times, the company had been hit hard since it was trying to deliver aggressive cost concessions to Buwing Canada - it's margin had fallen in 2012 and it had been loss making for two years. The company barely had any cash. Since it had maxed out its operating line of credits, it was not in a strong position to borrow from a bank. In 2012, Uli Importers sold $3.3 million to Buwing Canada, representing 60% of their overall sales. Buwing Discount was their only major retailer - 40% of their sales were to smaller independent shops in Quebec. Buwing Canada paid Uli Importers within 30 days. The contract was up for renewal in three more years, it had a clause that allowed Buwing Canada to make adjustments to the payment terms with written notice. Buwing Canada had four other suppliers of bed and bath products and had recently met another one through her U.S. counterpart. While she had enjoyed her working relationship with Uli Importers, she was uncertain about the company's financial strength and thought that it may be time to test whether they could handle being competitive with payment terms. In a meeting, she had mentioned to the company's owner that they would be seeking an extension of payment terms from 30 to 90 days. Exhibit 4 shows Turner-Plask and Uli Importers financial statements. What to do? Decisions needed to be reached. Within Buwing Canada, the president & CEO, Yvonne Fu, would need to decide whether it was appropriate to send the letter to the company's non-food suppliers to extend the credit terms to 90 days. If she decided against it, she would need to answer to the parent company's CFO, Georgina Monasconti, with a clear action plan to grow the days payable. The two suppliers Turner-Plask Potatoes and Uli Importers - both needed to decide how to approach Buwing Canada. While the balance of business with Buwing Canada was differently weighted for both suppliers, any decision was sure to have an indelible affect upon their businesses. 7 Exhibit 1 Buwing Discount Financial Statements Buwing Discount USD Millions CAD Millions Consolidated (Year Ending Jan 31) 2012 2011 2010 Canadian Stores (Year Ending Jan 31) 2012 2011 2010 Number of Stores 2755 2746 2733 255 253 245 INCOME STATEMENT 3,609 Net Sales % to Net Sales 44,568 7.4% 41,493 6.3% 39,023 5.2% 4,331 8.6% 3.987 10.5% 5.2% Cost of Sales 34,273 10,295 23.1% 32,033 9,460 22.8% 30,243 8.780 22.5% 3,340 991 Gross Profit Gross Profit Margin 3,093 894 2,805 804 22.9% 22.4% 22.3% 699 564 Operating Expenses EBITDA EBIT 7,666 2,630 2,134 662 292 234 240 202 7,095 2.365 1,933 609 1,324 3.2% 6,595 2,185 1,876 600 1,276 3.3% 646 248 203 71 132 3.3% Taxes 82 71 Net Income % to Net Sales 1,472 3.3% 152 3.5% 131 3.6% BALANCE SHEET Assets Cash & Cash Equivalents Receivables, net 983 624 189 34 176 33 Inventories Other Current 1,200 624 7,577 132 9,533 1,044 622 7.469 122 9,257 7,414 123 209 25 910 12 1,156 877 10 830 9 Current Assets 9.145 1,110 1,048 1.117 -335 1,067 -320 Property & Equipment Less Accumulated Depreciation Net Property Other Long-term Assets Total Assets 13,370 3,877 9,493 2893 21,918 12.448 -3,610 8,838 2763 20,858 11,707 -3,395 8,312 2345 19.802 782 267 1,093 -328 765 234 2,109 747 210 2,204 2.005 Liabilities & Equity Short-term borrowings Accounts Payable Other Current Liabilities Total Current Liabilities 36 297 403 3,850 1.456 5,709 421 3,510 1,272 5,203 440 3,231 1,275 4,946 32 311 140 483 35 277 128 134 467 440 Long-term Debt Other Long-term Liabilities Total Liabilities 5,041 1,209 11,959 5,006 1,373 11,582 4,950 1.234 422 107 402 103 376 98 11,131 1,012 972 914 Shareholders Equity Total Liabilities & Equity 9,959 21,918 9,276 20.858 8,671 19.802 1,192 2.204 1,138 2,109 1,091 2,005 5.1 80.7 5.5 85.1 5.8 89.5 2.1 99.4 3.1 103.5 3.3 108.0 Days Receivable Days in Inventory Days Payable Cash Conversion Cycle 41.0 40.0 39.0 34.0 35.0 36.0 44.8 50.6 56.3 67.5 71.6 75.4 Source: Case Writer 8 Exhibit 2 Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC) is a financial metric that shows the amount of time, in days, that it takes for a company to convert its products or services into cash. It is calculated by taking: Days Receivable + Days in Inventory Days Payable = Cash Conversion Cycle The objective of many companies is to reduce the cash conversion cycle by: 1. Decreasing Days Receivable 2. Decreasing Days in Inventory 3. Increasing Days Payable Calculations Days Receivable Accounts Receivable 365 days Net Sales Days in Inventory 365 days Inventories Cost of Sales X Days Payable Accounts Payable Cost of Sales x 365 days Source: Case Writer with reference to investopedia.com 9 Dalhousie University Buwing Discount: Extending Payment Terms Exhibit 4 Financial Statements: Turner-Plask Potatoes and Uli Importers Turner-Plask (in CAD 000s) Uli Importers (in CAD 000s) 2012 2011 2012 2011 INCOME STATEMENT 22.012 21,092 INCOME STATEMENT Net Sales % to Net Sales Net Sales % to Net Sales 5,894 5,485 -6.9% Cost of Sales Gross Profit Gross Profit Margin Operating Expenses EBIT 15,871 6,141 27.9% 5,481 660 15,123 5.969 28.3% 5.273 696 Cost of Sales Gross Profit Gross Profit Margin Operating Expenses EBIT 3,467 2,018 36.8% 2,435 -416.86 3,531 2,363 40.1% 2,570 -206.29 BALANCE SHEET Assets Cash & Cash Equivalents Receivables, net Inventories Long-term Assets Total Assets 218 1,087 1,609 2.340 5,254 199 1.023 1.497 2.333 5,052 BALANCE SHEET Assets Cash & Cash Equivalents Receivables, net Inventories Long-term Assets Total Assets 23 673 1,023 109 45 699 987 125 1,856 1,828 Liabilities & Equity Accounts Payable Long-term Debt Other Liabilities Total Liabilities 1,432 2,718 128 4,278 1,344 2,109 164 3,617 Liabilities & Equity Accounts Payable Long-term Debt Other Liabilities Total Liabilities 428 875 432 1,735 405 765 199 1,369 Shareholders Equity Total Liabilities & Equity 976 5,254 1,435 5,052 Shareholders Equity Total Liabilities & Equity 93 1,828 487 1,856 17.7 36.1 Days Receivable Days in Inventory Days Payable Cash Conversion Cycle 18.0 37.0 32.9 22.1 Days Receivable Days in Inventory Days Payable Cash Conversion Cycle 32.4 21.4 44.8 107.7 45.1 107.4 43.3 102.0 41.9 103.5 Note: Note: % of Business from Buwing 18.0% 3.962 % of Business from Buwing Sales to Buwing 60.0% 3,291 Sales to Buwing Source: Case WriterStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts