Question: Case 14 Please be as elaborate as possible, this is a Strategic Management university paper. The conclusion is the basic question. Identify the problems and

Case 14

Please be as elaborate as possible, this is a Strategic Management university paper.

The conclusion is the basic question. Identify the problems and give solutions. Give a complete SWOT and PESTEL analysis of the Case study (SWOT and PESTEL).

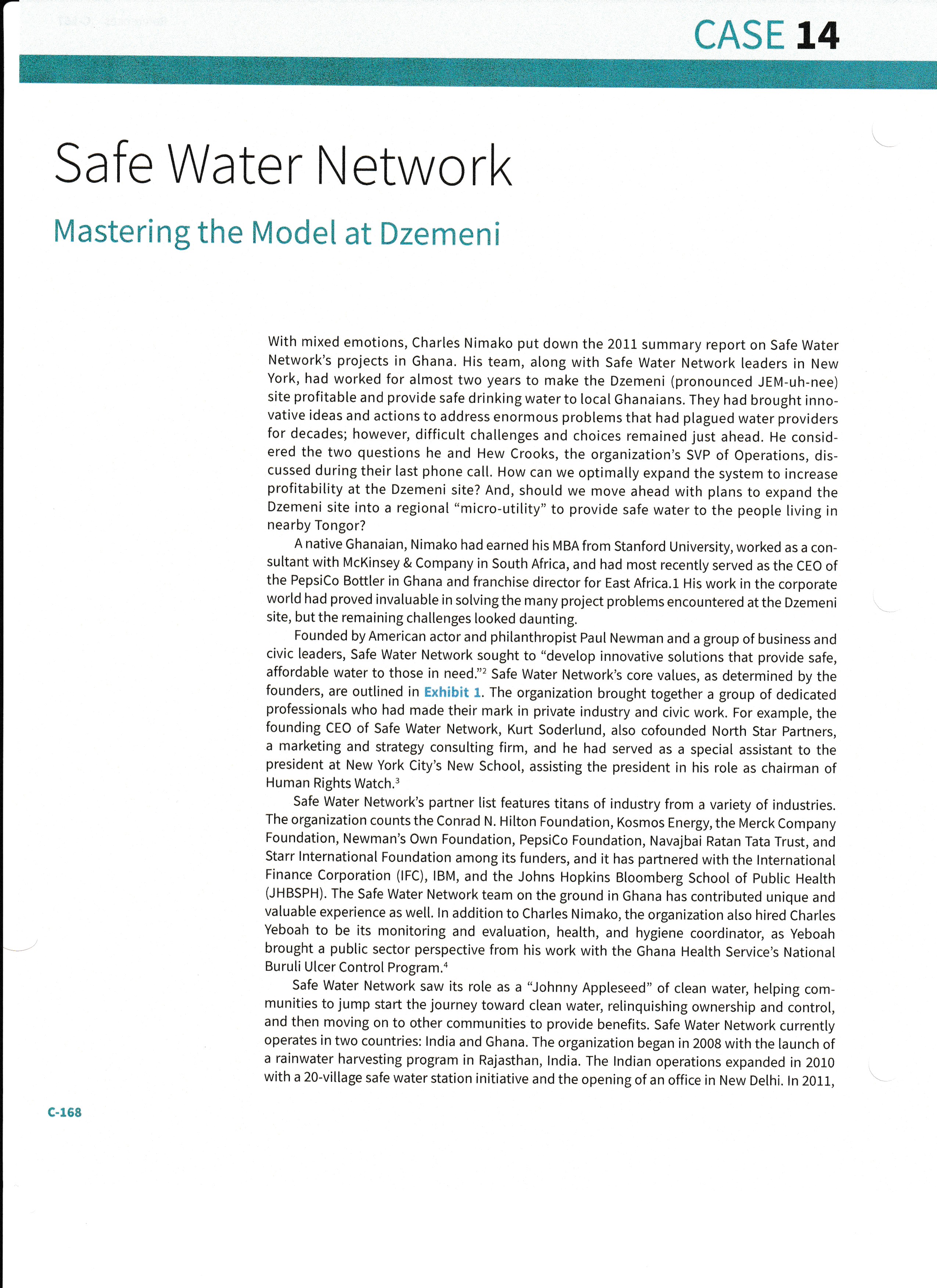

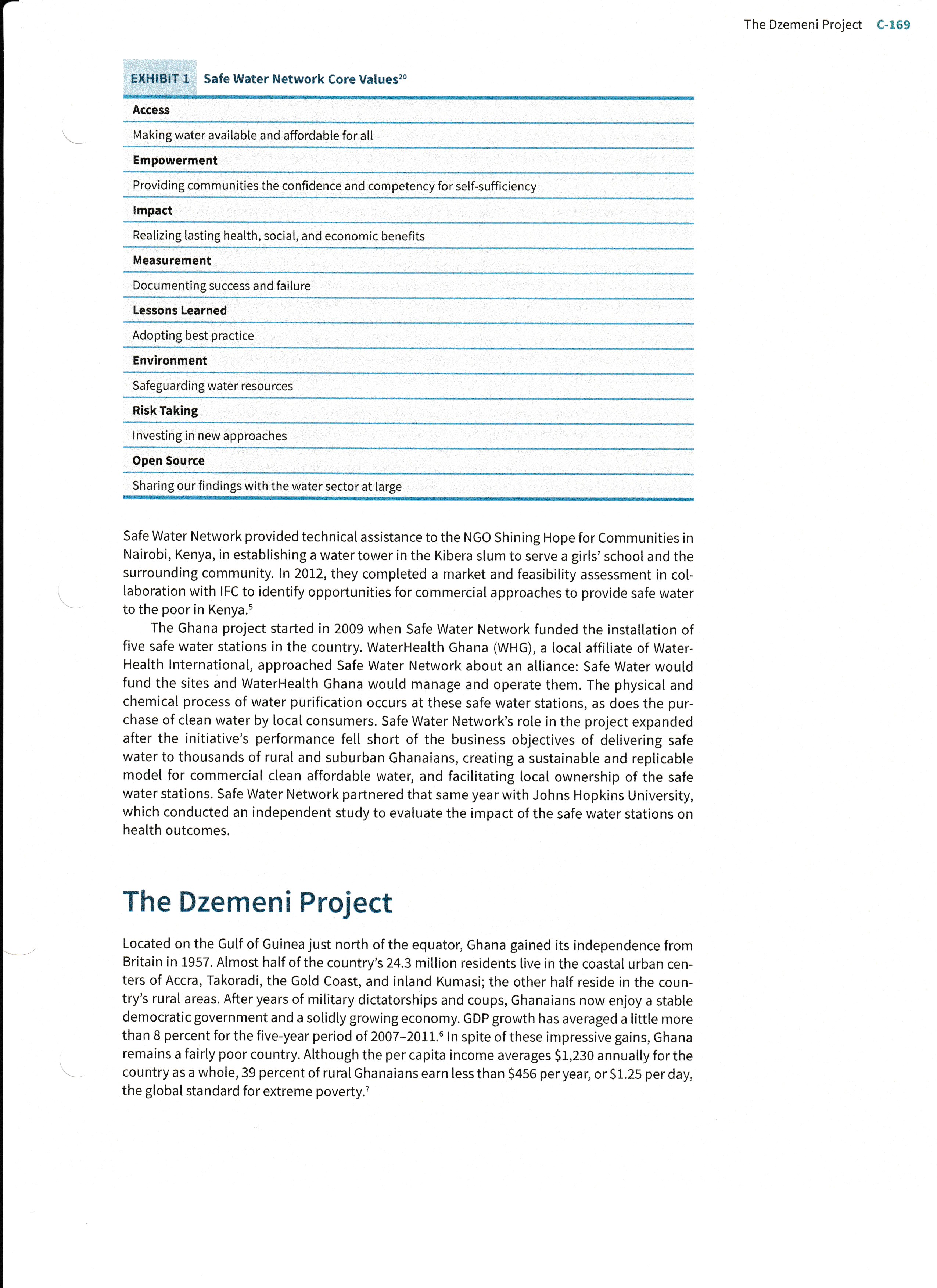

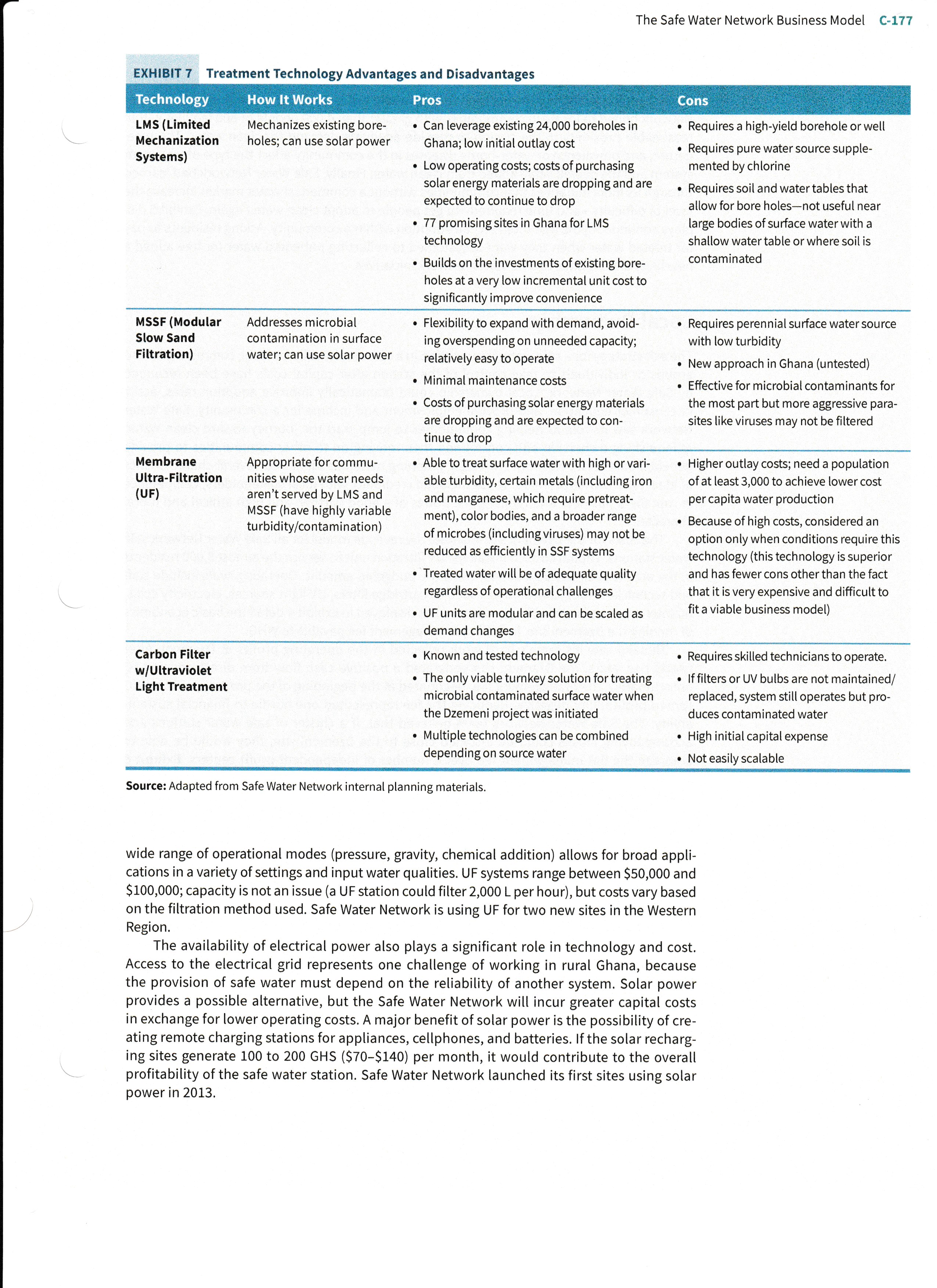

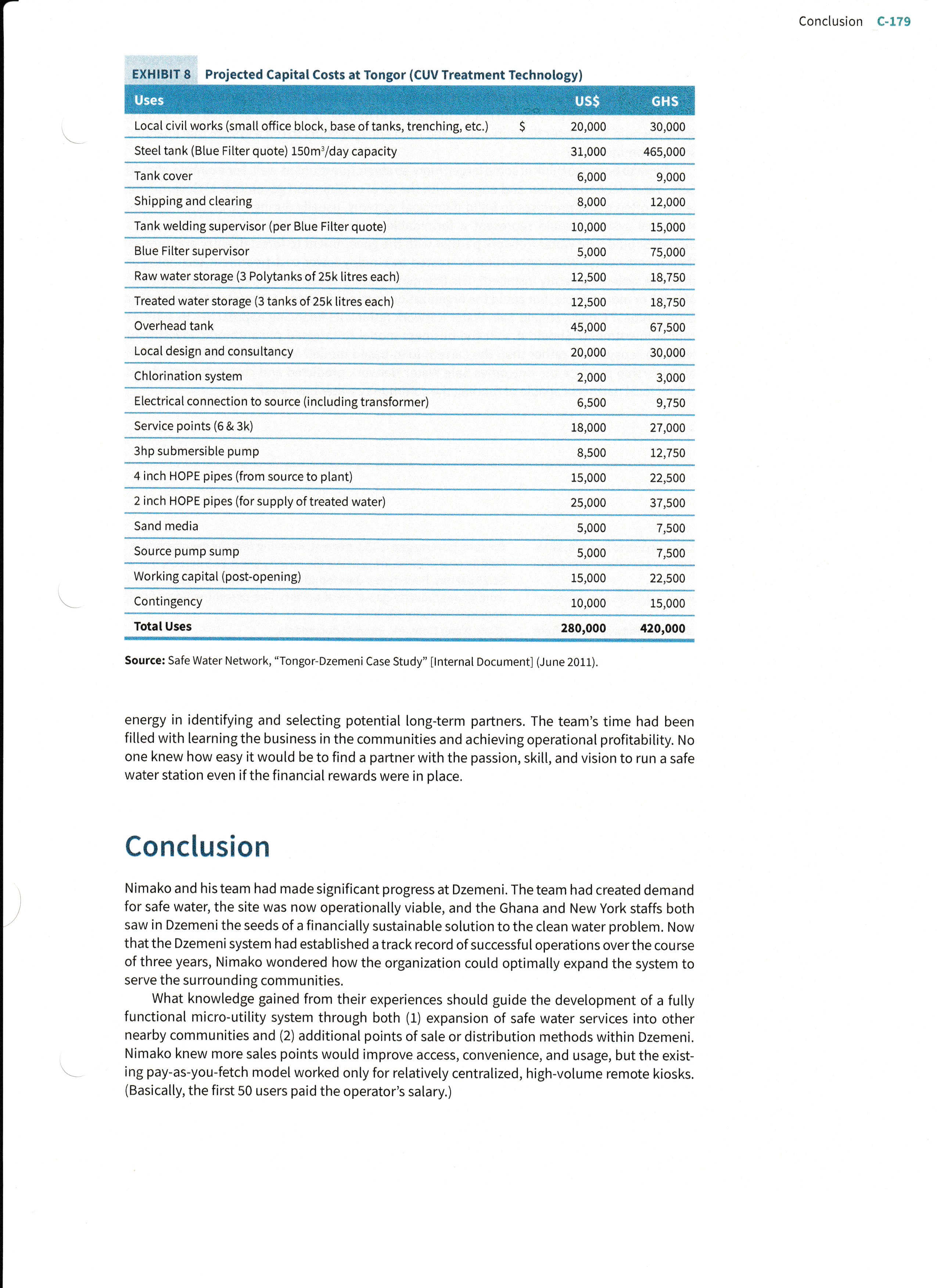

Safe Water Network Mastering the Model at Dzemeni With mixed emotions, Charles Nimako put down the 2011 summary report on Safe Water Network's projects in Ghana. His team, along with Safe Water Network leaders in New York, had worked for almost two years to make the Dzemeni (pronounced JEM-uh-nee) site profitable and provide safe drinking water to local Ghanaians. They had brought innovative ideas and actions to address enormous problems that had plagued water providers for decades; however, difficult challenges and choices remained just ahead. He considered the two questions he and Hew Crooks, the organization's SVP of Operations, discussed during their last phone call. How can we optimally expand the system to increase profitability at the Dzemeni site? And, should we move ahead with plans to expand the Dzemeni site into a regional "micro-utility" to provide safe water to the people living in nearby Tongor? A native Ghanaian, Nimako had earned his MBA from Stanford University, worked as a consultant with McKinsey \& Company in South Africa, and had most recently served as the CEO of the PepsiCo Bottler in Ghana and franchise director for East Africa.1 His work in the corporate world had proved invaluable in solving the many project problems encountered at the Dzemeni site, but the remaining challenges looked daunting. Founded by American actor and philanthropist Paul Newman and a group of business and civic leaders, Safe Water Network sought to "develop innovative solutions that provide safe, affordable water to those in need."' Safe Water Network's core values, as determined by the founders, are outlined in Exhibit 1. The organization brought together a group of dedicated professionals who had made their mark in private industry and civic work. For example, the founding CEO of Safe Water Network, Kurt Soderlund, also cofounded North Star Partners, a marketing and strategy consulting firm, and he had served as a special assistant to the president at New York City's New School, assisting the president in his role as chairman of Human Rights Watch. 3 Safe Water Network's partner list features titans of industry from a variety of industries. The organization counts the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, Kosmos Energy, the Merck Company Foundation, Newman's Own Foundation, PepsiCo Foundation, Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust, and Starr International Foundation among its funders, and it has partnered with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), IBM, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHBSPH). The Safe Water Network team on the ground in Ghana has contributed unique and valuable experience as well. In addition to Charles Nimako, the organization also hired Charles Yeboah to be its monitoring and evaluation, health, and hygiene coordinator, as Yeboah brought a public sector perspective from his work with the Ghana Health Service's National Buruli Ulcer Control Program. 4 Safe Water Network saw its role as a "Johnny Appleseed" of clean water, helping communities to jump start the journey toward clean water, relinquishing ownership and control, and then moving on to other communities to provide benefits. Safe Water Network currently operates in two countries: India and Ghana. The organization began in 2008 with the launch of a rainwater harvesting program in Rajasthan, India. The Indian operations expanded in 2010 with a 20-village safe water station initiative and the opening of an office in New Delhi. In 2011, C-168 Safe Water Network provided technical assistance to the NGO Shining Hope for Communities in Nairobi, Kenya, in establishing a water tower in the Kibera slum to serve a girls' school and the surrounding community. In 2012, they completed a market and feasibility assessment in collaboration with IFC to identify opportunities for commercial approaches to provide safe water to the poor in Kenya. 5 The Ghana project started in 2009 when Safe Water Network funded the installation of five safe water stations in the country. WaterHealth Ghana (WHG), a local affiliate of WaterHealth International, approached Safe Water Network about an alliance: Safe Water would fund the sites and WaterHealth Ghana would manage and operate them. The physical and chemical process of water purification occurs at these safe water stations, as does the purchase of clean water by local consumers. Safe Water Network's role in the project expanded after the initiative's performance fell short of the business objectives of delivering safe water to thousands of rural and suburban Ghanaians, creating a sustainable and replicable model for commercial clean affordable water, and facilitating local ownership of the safe water stations. Safe Water Network partnered that same year with Johns Hopkins University, which conducted an independent study to evaluate the impact of the safe water stations on health outcomes. The Dzemeni Project Located on the Gulf of Guinea just north of the equator, Ghana gained its independence from Britain in 1957. Almost half of the country's 24.3 million residents live in the coastal urban centers of Accra, Takoradi, the Gold Coast, and inland Kumasi; the other half reside in the country's rural areas. After years of military dictatorships and coups, Ghanaians now enjoy a stable democratic government and a solidly growing economy. GDP growth has averaged a little more than 8 percent for the five-year period of 20072011.6 In spite of these impressive gains, Ghana remains a fairly poor country. Although the per capita income averages $1,230 annually for the country as a whole, 39 percent of rural Ghanaians earn less than $456 per year, or $1.25 per day, the global standard for extreme poverty. World Bank data indicate that 80 percent of rural Ghanaians have access to "improved" water; however, water systems fail at an alarming rate. For example, the Ghanaian Ministry of Water Resources, Works, and Housing found that 30 percent of hand pumps did not function at all and another 50 percent operated incompletely. Between 40 and 45 percent of rural Ghanaians, roughly 4.6 million people, lack consistent access to clean water. Money allocated by the government toward clean water projects often gets diverted to other uses; in 2010, more than 90 percent of funds budgeted failed to be spent. Water-borne diseases such as diarrhea, Buruli ulcer, and intestinal worms run rampant among the population, with 70 percent of diseases in the country traceable to the lack of safe water. 8 Four of the five safe water stations served residents of the greater Accra peri-urban region (i.e., the area between the suburbs and the countryside), which include Amasaman, Pokuase, Obeyeyie, and Oduman. Exhibit 2 provides country-level data for Ghana, the two regions with safe water stations, and the five site locations. Dzemeni, located on the southeast shores of Lake Volta, represented the first attempt to reach rural and semirural Ghanaians. Lake Volta, formed in 1964 when the government dammed the Volta River at Akosombo Gorge, is one of the largest manmade lakes in the world. 9 Dzemeni residents can draw water directly from the lake; however, decades of human and animal use have resulted in levels of microbial pollution that leave the water unsuitable for human use. With about 7,000 residents, Dzemeni exists primarily as a market town and urban center, and it serves as a trading center for about 15,000 Ghanaians in the outlying hamlets. The Dzemeni safe water site made sense to Safe Water Network for several reasons. First, Dzemeni had no municipal water source and no other commercial water vendors existed; the convenience of Lake Volta effectively eliminated competition. Since it first appeared, residents Source: SWN internal planning documents. have drawn water out of the lake, in spite of its contaminated state. Second, Safe Water Network research indicated that more than 50 percent of residents, while poor, could reasonably afford to purchase clean water. Third, Safe Water Network was able to identify community leaders who would create excitement about safe water stations and encourage educational efforts that stressed the importance of clean water. Finally, nearby Tongor, which was also a combination of a number of villages, provided another potential market if the safe water station could profitably scale its operation. 10 Delays and problems, however, cropped up almost immediately. Locating, screening, and selecting sites took longer than expected. Negotiations with community leaders at selected sites took time, and the sites required different water purification systems to address specific challenges. The Dzemeni center opened 18 months behind schedule, and capital costs for construction of the site exceeded its budget by 80 percent. Operating performance fell short of expectations; sales volumes indicated penetration rates (the percent of the population using the safe water station) around 20 percent instead of the 75 percent target, and the facilities failed to even cover operating costs. In late 2010, Safe Water Network replaced WHG as the controlling partner. Safe Water managed health and hygiene education, marketing and demand development, and overall management at the Dzemeni site (as well as the other four sites). WHG continued its role as the Dzemeni site technical operator. 11 Nimako and his local team began the hard work required to solve the many problems that stymied success. Safe Water Network began to learn that even the first goal, providing affordable potable water to rural Ghanaians, proved elusive and difficult, even more difficult than they expected. The Water Users-Customers Although the need for water is universal to humans, the demand for safe water is dependent on a variety of factors, including price sensitivity, convenience, seasonal variation in demand, and consumer knowledge about the benefits of clean water. Price Sensitivity Before the management transition to Safe Water Network began, in order to stem operating losses, WHG had doubled the price of water from 0.05 Ghana cedis (GHS) or 5 pesewas (p) -about $0.035 to 0.10GHS or $0.07 for 20 liters (20L). An average person needs 7L of safe water for drinking and cooking each day, according to the WHO, and a family of five would use about 40L per day. Overall demand dropped 30 percent immediately after the price increase, and the reduction in demand from the poorest Ghanaians, those Safe Water Network most wanted to reach, likely exceeded that figure. Incomes for the 40 percent living below the $1.25 per day poverty line averaged $1.08 per day, or $5.40 for a family of five. 12 These families would have to spend about 2 percent of their income on commercial water, and studies from the Johns Hopkins group indicated that "cost did not seem to be a barrier to use." 13 In spite of increased operating costs, Safe Water Network ruled out any further price increases that would put the stations' water out of reach of the poorest consumers, committing instead to achieving sustainability through increasing consumption and reducing costs. The Convenience Factor Water is heavy! A 20L container weighs nearly 45 pounds, and not only did the spending of hard-earned cash for the water dampen demand but so did the physical energy required to transport water from the station to the home. Safe Water Network mapped water purchasers and found usage to be highly dependent on distance. For example, in Pokuase, they found that 85 percent of those living within 100m (just short of the length of a football field) purchased water, but purchasing fell to 55 percent for those living between 100 and 200m from the site, and only 10 percent of those living beyond 200m made the effort to buy clean water. Dzemeni exhibited a similar pattern, with use dropping substantially for customers who lived further than 300m from the site. Exhibit 3 details the effect of convenience on water consumption. Safe Water Network decided to pipe water to remote kiosks (sales stations) some 400m away from the main station to increase demand and consumption. The remote kiosks almost doubled sales at Dzemeni. The increased water sales, combined with the low incremental operating costs of the remote kiosks, significantly improved the economics of the safe water stations in these sites. Exhibit 4 illustrates the economics at the Dzemeni site. Total system cost per liter declined by 33 percent in Dzemeni after the remote kiosks were installed. Safe Water Network leveraged its positive experience and installed remote kiosks in two additional communities and early results are promising. 14 EXHIBIT 3 The Effect of Convenience on Water Purchases A. Household Mapping in Pokuase Source: Safe Water Network, "Decentralized Safe Water Kiosks," [Internal Document] (August 2012). Available at http://www.issuelab.org/resource/decentralized_safe_water_kiosks_working_toward_a_sustainable_model_ in_ghana. Reproduced with permission of Safe Water Network. The Water Users-Customers C-173 B. Remote Kiosk Impact on Sales Volumes in Dzemeni and Pokuase Source: Safe Water Network, Decentralized Safe Water Kiosks," [Internal Document] (August 2012), http://www .issuelab.org/resource/decentralized_safe_water_kiosks_working_toward_a_sustainable_model_in_ghana. EXHIBIT 4 Comparison of Actual and Pro Forma Monthly Results at the Dzemeni Site Source: Safe Water Network, internal company documents. The Safe Water Network Business Model C-175 the impressive increases in demand for Safe Water products, the revenues generated covered only the operating expenses. Nimako wondered whether demand would ever cover the full costs of the Safe Water Stations and whether the fundamental business model and cost structure of Safe Water Network would need to change in order for the company to stay in business. The Safe Water Network Business Model Safe Water Network envisioned solving the challenge of potable water by creating financially sustainable and community-welcoming safe water facilities. The organization believed that if it could accomplish these goals, a third goal could be reached: finding local owners to buy and run the safe water stations. Taken together, these three overarching goals constituted the Safe Water Network objective. Nimako had an emerging understanding of the consumer side of the safe water initiative, and he mentally reviewed each pillar of Safe Water Network's business model. Exhibit 6 shows the Safe Water Network process for implementing the safe water initiative in a rural community. Financial Sustainability Rain water is pure; the evaporation process removes inorganic pollutants-chemicals, sediments, residues-as well as bacteria or other organic contaminants. Unfortunately, many "fresh water" sources in Ghana, such as Lake Volta, streams, wells, or springs, provide contaminated or impure water because of the presence of inorganic chemicals and minerals or EXHIBIT 6 The Safe Water Network Implementation Process Source: Safe Water Network, Tools for Safe Water. Stations, p. 125. Reproduced with permission of Safe Water Network. microbial contaminants associated with human or livestock fecal matter in the water. The essence of Safe Water Network's mission involves purifying impure water by moving it through a treatment system. The physical and biological characteristics of the water source drive the choice of treatment technology, which in turn underlies the financial sustainability of the Safe Water Network business model. The technology then determines the capital cost of the system. The cost of equipment identified as suitable for community-sized systems in Ghana ranges from \$23,000 (32,600 GHS) to $100,000 (142,000 GHS), not including land, building, and permitting costs (see technology descriptions below). Consumables such as sand, gravel, chemicals, membranes, operator and staff salaries, and maintenance expenses constitute operating costs. Safe Water Network has no allegiance to any particular technology, and leaders seek to install the most appropriate and cost-effective technology for a given site. Exhibit 7 describes the advantages and disadvantages of each treatment technology. Carbon filter with ultraviolet light treatment (CUV). All five initial sites in Ghana used CUVbased systems. These systems employ sand, carbon, and 10- and 1-micron polypropylene wound cartridge filters in addition to ultraviolet (UV) treatment systems. Water passes through a carbon filter and a series of other filters to remove chlorine, sediment, and other inorganic compounds. Exposure to UV light alters organic DNA and kills bacteria, viruses, yeast, mold spores, fungi, algae, and fecal coliform. 18 CUV systems cost $50,000$90,000 to purchase and install. This system may prove to be the most costly technology to operate because it requires well-trained technicians to operate the systems. Limited mechanization systems (LMS). LMS involves installing a submersible pump in a newly drilled or existing borehole (well), pumping water to an elevated water storage tank, and distributing the water via gravity to standpipes. This system does not provide water filtration; it only provides more water from existing boreholes. The water produced must be chlorinated before distribution to guarantee purity. The cost of LMS varies according to number of boreholes and pumps and the size of the storage tank. Safe Water Network's budgeted LMS costs are $23,000 for 1,000 people, $32,500 for 2,000 people, or $48,000 for 5,000 people. The use of solar power would reduce operating costs but increase capital outlay by $5,000$6,000. Safe Water Network is evaluating the use of LMS technology for a possible expansion in the Eastern Region. Modular slow sand filtration (MSSF). Slow sand filtration (SSF) has been in use since the early nineteenth century; however, in the last few years, the design and construction of modular systems has made MSSF an attractive method for smaller communities in the developing world. The system is appropriate and suitable for perennial surface water sources with low turbidity (mud and sediment). The system consists of twin modular plastic tanks for use as the main filter, supported with plastic raw and treated water storage tanks. The treated water is distributed by gravity, pumping, or a combination of the two, depending on the size of the system and the location and distribution of a remote kiosk. MSSF systems run $43,000 for 1,000 people, $47,000 for 2,000 people, and $69,500 for 5,000 people. Safe Water Network is employing MSSF at two new sites launched in the spring of 2013, in preparation for a larger-scale MSSF-based expansion planned around Lake Volta. Ultra-filtration (UF). UF utilizes a range of polymeric-based semipermeable membranes to filter particulates of different sizes. UF provides a filtering solution for communities with surface water sources but variable levels of turbidity or contamination. Primarily used in industrial settings, the technology has recently shown potential for adaption in developing world settings. Its The Safe Water Network Business Model C- 177 wide range of operational modes (pressure, gravity, chemical addition) allows for broad applications in a variety of settings and input water qualities. UF systems range between $50,000 and $100,000; capacity is not an issue (a UF station could filter 2,000L per hour), but costs vary based on the filtration method used. Safe Water Network is using UF for two new sites in the Western Region. The availability of electrical power also plays a significant role in technology and cost. Access to the electrical grid represents one challenge of working in rural Ghana, because the provision of safe water must depend on the reliability of another system. Solar power provides a possible alternative, but the Safe Water Network will incur greater capital costs in exchange for lower operating costs. A major benefit of solar power is the possibility of creating remote charging stations for appliances, cellphones, and batteries. If the solar recharging sites generate 100 to 200GHS($70$140) per month, it would contribute to the overall profitability of the safe water station. Safe Water Network launched its first sites using solar power in 2013. EXHIBIT 8 Projected Capital Costs at Tongor (CUV Treatment Technology) Source: Safe Water Network, "Tongor-Dzemeni Case Study" [Internal Document] (June 2011). energy in identifying and selecting potential long-term partners. The team's time had been filled with learning the business in the communities and achieving operational profitability. No one knew how easy it would be to find a partner with the passion, skill, and vision to run a safe water station even if the financial rewards were in place. Conclusion Nimako and his team had made significant progress at Dzemeni. The team had created demand for safe water, the site was now operationally viable, and the Ghana and New York staffs both saw in Dzemeni the seeds of a financially sustainable solution to the clean water problem. Now that the Dzemeni system had established a track record of successful operations over the course of three years, Nimako wondered how the organization could optimally expand the system to serve the surrounding communities. What knowledge gained from their experiences should guide the development of a fully functional micro-utility system through both (1) expansion of safe water services into other nearby communities and (2) additional points of sale or distribution methods within Dzemeni. Nimako knew more sales points would improve access, convenience, and usage, but the existing pay-as-you-fetch model worked only for relatively centralized, high-volume remote kiosks. (Basically, the first 50 users paid the operator's salary.) Likewise, if the company pursued a multitown micro-utility, what elements of the process should it replicate in order to deal with the inevitable cultural differences, even among local villages? How would the company solve the management challenges? Private system operators in Ghana have said that they would not be interested in managing a system as small as Dzemeni, so how would Safe Water Network select and train entrepreneurs to run a system that spanned several communities? Nimako began to think of some larger, more strategic questions as well. For example, should Safe Water Network partner and engage with the local or Ghanaian government? Government leaders often made promises to build municipal systems, usually during the election season. Municipal systems would represent a formidable competitor to the Safe Water Network's model. Should Safe Water Network partner with the government to forestall entry and protect their investments? What opportunities existed to employ lower-cost treatment technologies than the system currently installed? The Dzemeni model worked for aggregated communities of 7,000 or more people, but could the organization create safe water stations to service smaller communities? Finally, should Safe Water Network rethink its financing approaches to support capital investment? Should it shift the business model to targeted philanthropic investment (with no repayment) rather than the current loan-based model? Would the financial rewards of ownership produce the outcomes Safe Water Network predicted and create dedicated and skilled local partners capable of running the community water business? References 1http// www.safewaternetwork.org/team.asp, accessed March 8, 2013. 'Internal Safe Water Network, FAQ, https://www.safewaternetwork .org/faqs, accessed February 19, 2013. 3K. Soderland, http://www.safewaternetwork.org/Team.asp, accessed February 20, 2013. 4 Information on the leadership team of Safe Water Network taken from http://www.safewaternetwork.org/team.asp, accessed February 4, 2014. 5 Information drawn from internal Safe Water Network documents. 6 Calculated from data available through the World Bank, http://databank . worldbank.org/ddp/home.do?Step=3\&id=4, accessed February 20, 2013. 'I Ibid. 8Safe Water Network, "Decentralized Safe Water Kiosks" [Internal Document] (August 2012), p. 3. 'Safe Water Network, "Tongor-Dzemeni Case Study," [Internal Document] (June 2011), p. 5. 10 Ibid. 11 lbid. 12 This figure was calculated from the Poverty Gap Index, a measure designed to assess the intensity of poverty for those living in extreme poverty. The gap measures the average measured gap between the actual measured household income and the poverty line. For Ghana, the rural poverty gap is 13.5 percent, meaning that the average household income of those living below the poverty line is 13.5 percent below $1.25 per day. Poverty gap data found at http://www.tradingeconomics .com/ghana/poverty-gap-at-rural-poverty-line-percent-wb-data.html, accessed February 19, 2013. 13 Safe Water Network, internal documents. 14 Safe Water Network, "Remote Kiosks: A Path to Improved Economics and Coverage" [Internal Report] (2013). 15 Decentralized Safe Water Kiosks, pp. 8-9. 16 Data on Ghana taken from http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHome Page/geography/climate.php, and data for the United States taken from http://www.livescience.com/1558-study-reveals-top-10-wettest-cities .html, accessed February 20, 2013. 17 Decentralized Safe Water Kiosks, p. 10. 18A description of different treatment technologies can be found at Engineers Without Borders, http://www.stevens.edu/ewb/docs /ME423_Fall_07_Phase_III_Group_10_EWB_-_Water_Purification.pdf, accessed February 21, 2013. 19 Personal communication between the case writer and Safe Water Network leaders. 20http:// www.safewaternetwork.org/Values.asp, accessed February4, 2013

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

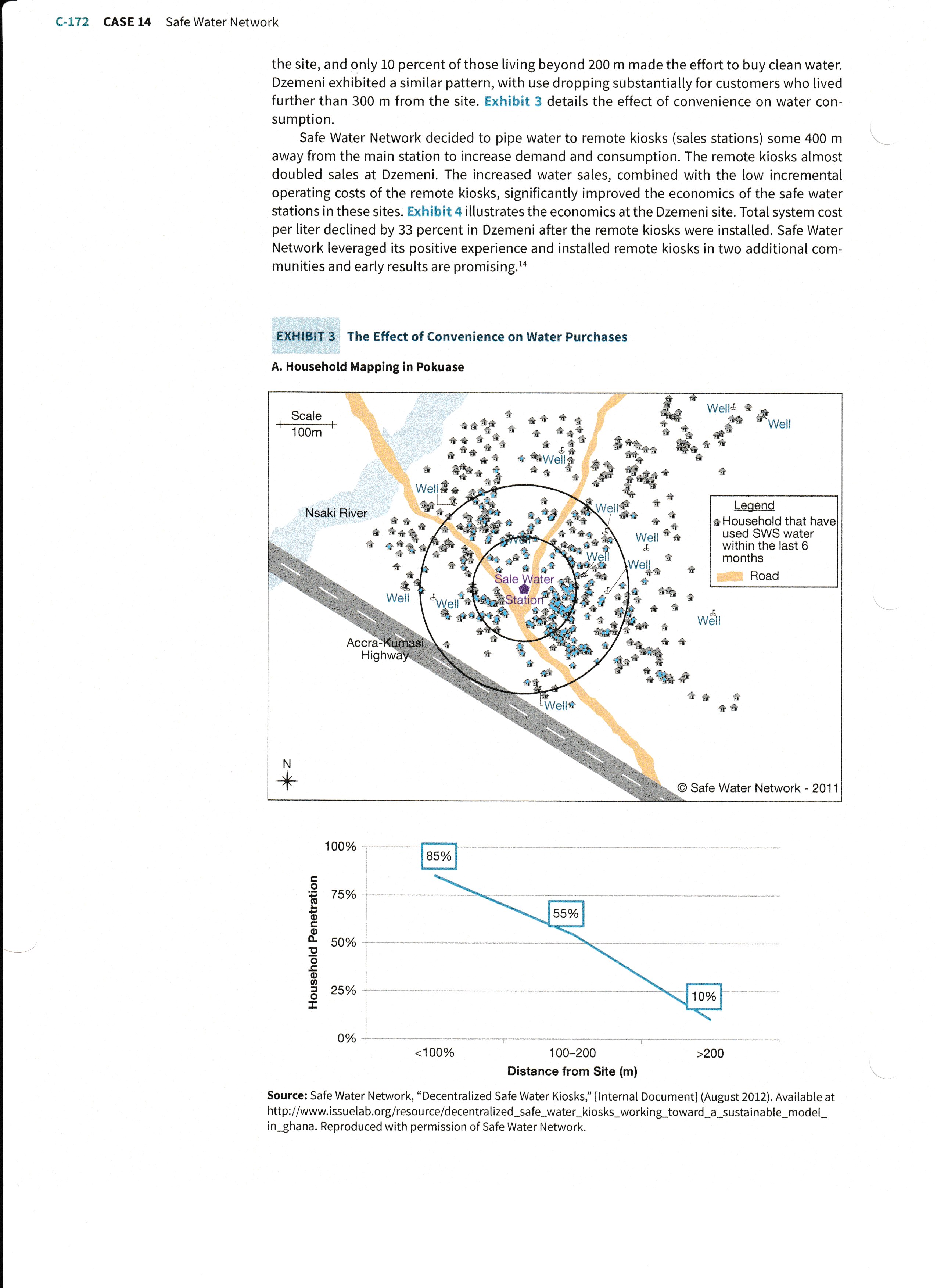

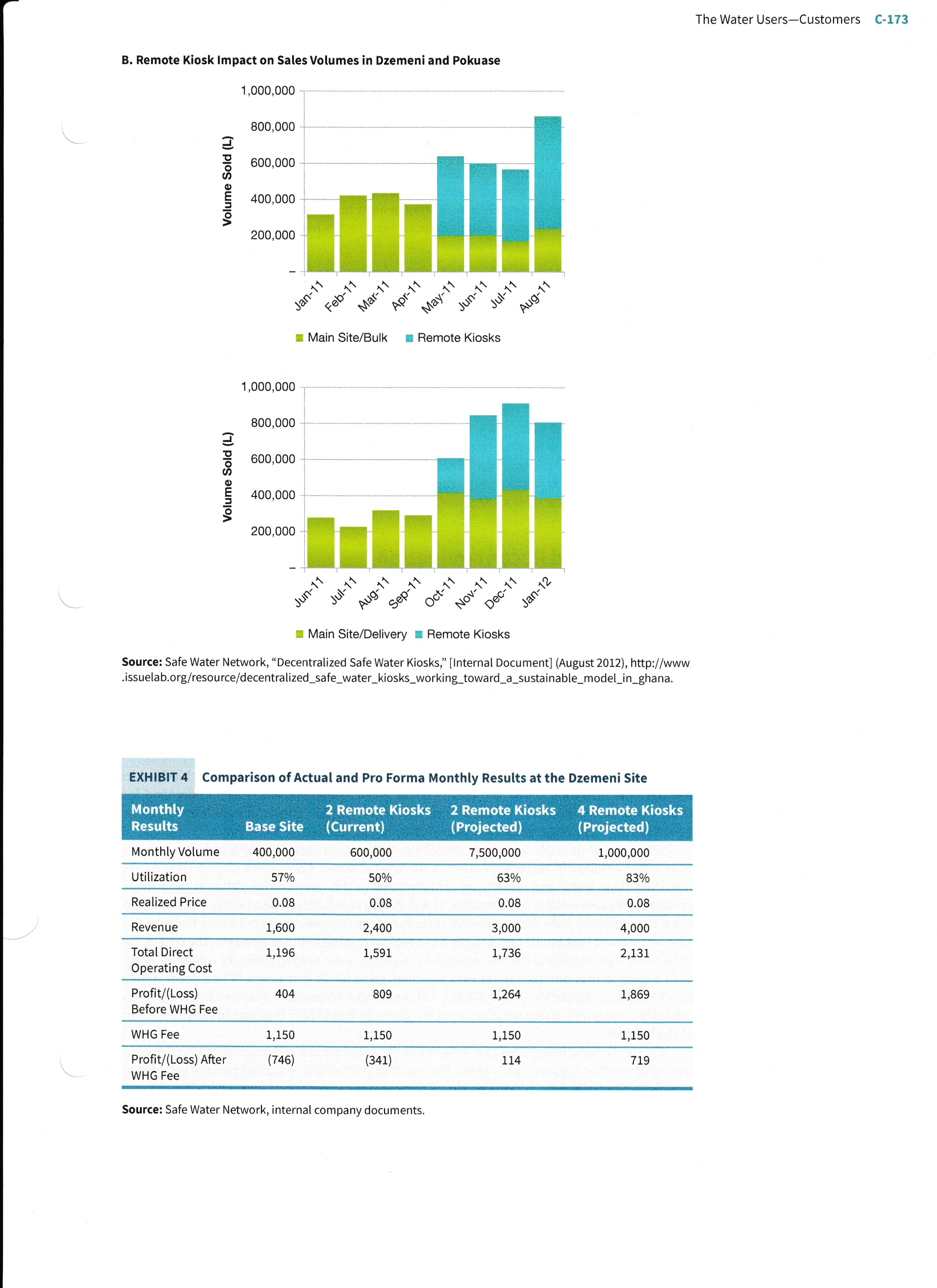

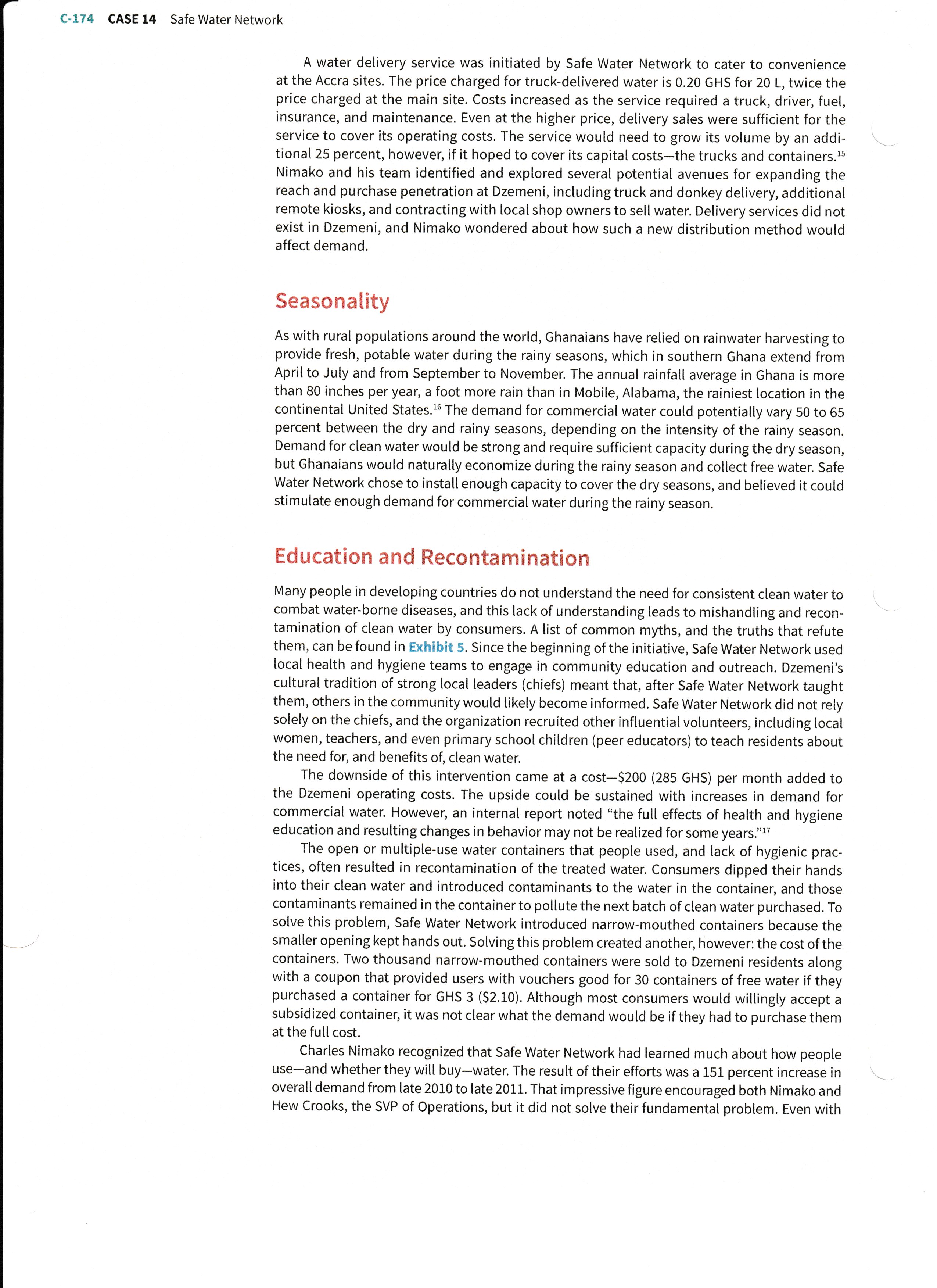

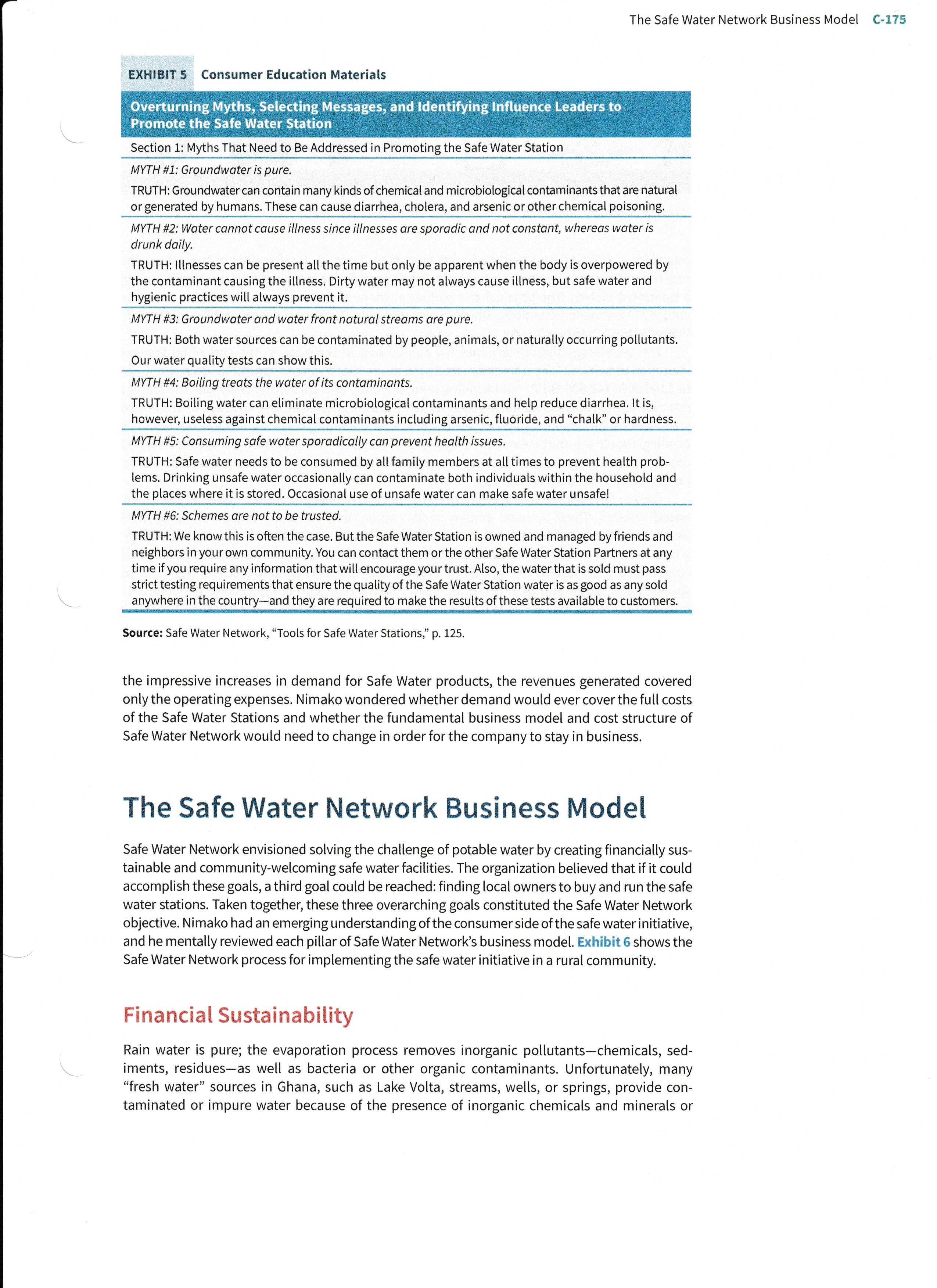

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts