Question: CASE ANALYSIS A. Identify the specific accounting issues involving this case. B. Identify, if any, all cases of misstatements, the manager assertions that are compromised,

CASE ANALYSIS

A. Identify the specific accounting issues involving this case.

B. Identify, if any, all cases of misstatements, the manager assertions that are compromised, and the effects of those misstatements on significant account balances.

C. Identify the internal control weaknesses that contributed to the misstatements you have identified.

D. Articulate the type of audit opinion, given your overall analysis of this case, you would issue on the overall financial statements of the entity.

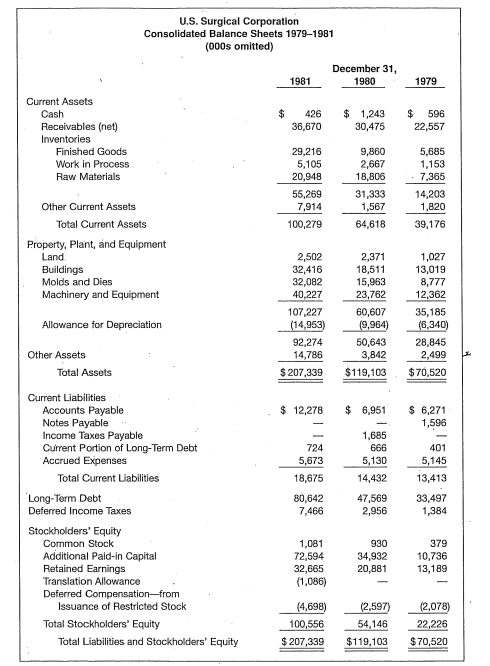

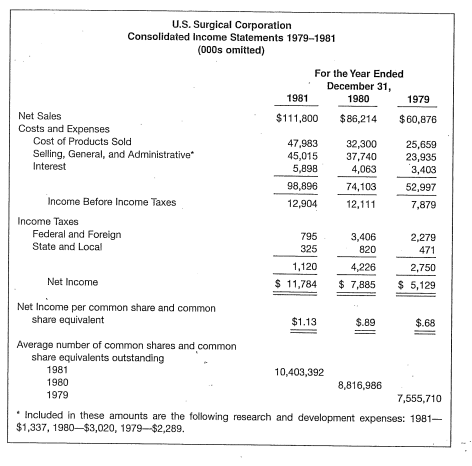

UNITED STATES SURGICAL CORPORATION Leon Hirsch founded United States Surgical Corporation (USSC) in 1964 with very little capital, four employees, and one product: an unwieldy mechanical de vice that he intended to market as a surgical stapler. In his mid-thirties at the time and lacking a college degree, Hirsch had already tried several lines of business, including frozen foods, dry cleaning, and advertising, each with little success. In fact, the dry cleaning venture ended in bankruptcy. No doubt, few of Hirsch's friends and family members believed that USSC would become financially viable. Despite the long odds against him, in a little more than one decade Hirsch had built the Connecticut-based USSC into a large and profitable public company whose stock was traded on a national exchange. More importantly, the surgical stapler that Hirsch invented revolutionized surgery techniques in the United States and abroad. During the early years of its existence, USSC dominated the small surgical sta- pling industry that Hirsch had established in the mid-1960s. By 1980, several companies were encroaching on USSC's domestic and foreign sales markets. USSC's principal competitor at the time was a company owned by Alan Black- man. Blackman's company sold its products primarily in foreign countries but was attempting to significantly expand its U.S. sales. Hirsch alleged that Black- man, who was a former friend and associate, had infringed on USSC's patents by "reverse-engineering" the company's products. In the early 1980s, USSC began an aggressive counterattack to repel Black- man's intrusion into its markets. First, USSC adopted a worldwide litigation strat- egy to contest Blackman's right to manufacture and market his competing products. Second, the company embarked on a large research and development program to create a line of new products technologically superior to those being manufactured by Blackman. Each of these initiatives required multimillion-dollar commitments by USSC-commitments that threatened the company's steadily rising profits and Hirsch's ability to raise additional capital that USSC desper- ately needed to finance its rapid growth. Hirsch overcame the major challenges facing his company. USSC maintained its dominant position in the surgical stapling industry, while continuing to report record profits and sales each year. Ironically, those record profits and sales even- tually spelled trouble for the company. Mounting suspicion that USSC's reported operating results were too good to be true prompted the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to launch an investigation of the company's financial affairs. In 1983, the SEC leveled several charges of misconduct against key USSC officers, including Leon Hirsch. Within a short time, USSC's audit firm, Ernst & Whinney, resigned and withdrew the unqualified audit opinions it had issued on the com- pany's 1980 and 1981 financial statements. In 1985, the SEC released a report on its lengthy investigation of USSC. The SEC ruled that the company had used a "variety of manipulative devices to overstate its earnings in its 1986 and 1981 fi- nancial statements."1 (Exhibit 1 contains USSC's original balance sheets and in- come statements for the period 1979 to 1981.) To settle the SEC charges, USSC officials signed an agreement with the federal agency that forced the company to reduce its previously reported earnings by $26 million. Additionally, senior executives of USSC agreed to return to the company large bonuses they had been paid during 1980 and 1981. Hirsch alone repaid more than $300,000 to USSC. Following the signing of the agreement with the SEC, Hirsch reported that the criticism of his company and his management decisions was undeserved. Hirsch implied that cost considerations motivated him to accept the SEC sanctions: "It was our opinion that the settlement (with the SEC) was preferable to long, costly and time-consuming litigation."2 USSC'S ABUSIVE ACCOUNTING PRACTICES The enforcement release that disclosed the key findings of the SEC's investigation of USSC charged the company with several abusive accounting and financial re- porting practices. A focal point of the SEC's investigation was an elaborate scheme that USSC executives implemented to charge inventoriable production costs to a long-term asset account, molds and dies. This scheme, which required the cooperation of several of USSC's vendors, was deliberately concealed from the company's audit firm, Ernst & Whinney. The SEC investigation also revealed that USSC recorded inventory shipments to its sales force as consummated sales transactions. Until the mid-1970s, USSC had marketed its products through a network of independent dealers. Histori- cally, inventory shipments to these dealers had been treated as arm's length transactions and thus reportable as revenue. By 1980, the company marketed its products almost exclusively through a sales staff consisting of full-time employ- ees working on a commission basis. Each member of the sales staff maintained an inventory of USSC products, which they transported from client to client. In 1980 and 1981, USSC's management began intentionally shipping excessive amounts of inventory to its sales staff. A former USSC sales manager later testi- fied regarding this practice. "It was nothing to come home and find $3,000 worth of product sitting in a box on your front porch from UPS and a note saying, "We thought you needed a little more product. 4 According to the SEC, USSC's pol- icy of recognizing inventory shipments to its sales staff as consummated sales transactions inflated the company's 1980 and 1981 pre-tax profits by $1,150,000 and $750,000, respectively. The SEC also charged that USSC abused the accounting rule that permits the capitalization of legal expenditures incurred to develop and successfully defend a patent. In 1980, the company capitalized less than $1 million of such expendi- tures; the following year, that figure leaped to $5.8 million. The SEC investigation disclosed that a significant portion of the 1981 litigation expenditures stemmed from Australian lawsuits filed against Alan Blackman and his company. Because USSC did not have any registered patents in Australia, these expenditures should have been immediately charged to operations instead of being deferred in an asset account. Approximately $3.7 million of USSC's 1981 litigation expenditures involved efforts to defend the company's U.S. patents. However, USSC chose to amortize these costs over a 10-year period even though the 17-year legal life of most of the patents would expire in 1983 or 1984. USSC leased, rather than sold, many of its surgical tools. The company's ac- counting staff recorded the cost of these assets in a subsidiary fixed asset ledger, leased and loaned assets. USSC periodically retired such assets and removed their accounts from the sub-ledger. However, SEC investigators discovered that in many cases the costs associated with these assets were not removed from the sub-ledger but instead debited to the accounts of other assets still in service. In 1981, USSC also understated depreciation expense on several fixed assets by ar- bitrarily extending their useful lives and establishing salvage values for them for the first time. U.S. Surgical Corporation Consolidated Balance Sheets 1979-1981 (000s omitted) December 31, 1980 1981 1979 $ 426 36,670 $ 1,243 30,475 $ 596 22,557 Current Assets Cash Receivables (net) Inventories Finished Goods Work in Process Raw Materials 29,216 5,105 20,948 55,269 7,914 100,279 9,860 2,667 18,806 31,333 1,567 64,618 5,685 1,153 7.365 14,203 1,820 39,176 Other Current Assets Total Current Assets Property, Plant, and Equipment Land Buildings Molds and Dies Machinery and Equipment 2,502 32,416 32,082 40,227 107,227 (14,953) 92,274 14,786 $ 207,339 2,371 18,511 15,963 23,762 60,607 (9,964) 50,643 3,842 $119,103 1,027 13,019 8,777 12,362 35,185 (6,340) 28,845 2,499 $ 70,520 Allowance for Depreciation Other Assets Total Assets $ 12,278 $ 6,951 $ 6,271 1,596 724 5,673 18,675 1,685 666 5,130 14,432 401 5,145 13,413 80,642 7,466 47,569 2,956 33,497 1,384 Current Liabilities Accounts Payable Notes Payable Income Taxes Payable Current Portion of Long-Term Debt Accrued Expenses Total Current Liabilities Long-Term Debt Deferred Income Taxes Stockholders' Equity Common Stock Additional Paid-in Capital Retained Earnings Translation Allowance Deferred Compensationfrom Issuance of Restricted Stock Total Stockholders' Equity Total Liabilities and Stockholders' Equity 1,081 72,594 32,665 (1,086) 930 34,932 20,881 379 10,736 13,189 (4,698) 100,556 $207,339 (2,597) 54,146 $119,103 (2,078) 22,226 $ 70,520 U.S. Surgical Corporation Consolidated Income Statements 1979-1981 (000s omitted) For the Year Ended December 31, 1980 1979 1981 $111,800 $86,214 $ 60,876 Net Sales Costs and Expenses Cost of Products Sold Selling, General, and Administrative Interest 47.983 45,015 5,898 98,896 12,904 32,300 37,740 4,063 74,103 12,111 25,659 23,935 3,403 52,997 7,879 Income Before Income Taxes Income Taxes Federal and Foreign State and Local 795 325 1,120 $ 11,784 3,406 820 4,226 $ 7,885 2,279 471 2,750 $ 5,129 Net Income Net Income per common share and common share equivalent $1.13 $.89 $.68 Average number of common shares and common share equivalents outstanding 1981 10,403,392 1980 8,816,986 1979 7,555,710 Included in these amounts are the following research and development expenses: 1981- $1,337, 1980-$3,020, 1979$2,289. UNITED STATES SURGICAL CORPORATION Leon Hirsch founded United States Surgical Corporation (USSC) in 1964 with very little capital, four employees, and one product: an unwieldy mechanical de vice that he intended to market as a surgical stapler. In his mid-thirties at the time and lacking a college degree, Hirsch had already tried several lines of business, including frozen foods, dry cleaning, and advertising, each with little success. In fact, the dry cleaning venture ended in bankruptcy. No doubt, few of Hirsch's friends and family members believed that USSC would become financially viable. Despite the long odds against him, in a little more than one decade Hirsch had built the Connecticut-based USSC into a large and profitable public company whose stock was traded on a national exchange. More importantly, the surgical stapler that Hirsch invented revolutionized surgery techniques in the United States and abroad. During the early years of its existence, USSC dominated the small surgical sta- pling industry that Hirsch had established in the mid-1960s. By 1980, several companies were encroaching on USSC's domestic and foreign sales markets. USSC's principal competitor at the time was a company owned by Alan Black- man. Blackman's company sold its products primarily in foreign countries but was attempting to significantly expand its U.S. sales. Hirsch alleged that Black- man, who was a former friend and associate, had infringed on USSC's patents by "reverse-engineering" the company's products. In the early 1980s, USSC began an aggressive counterattack to repel Black- man's intrusion into its markets. First, USSC adopted a worldwide litigation strat- egy to contest Blackman's right to manufacture and market his competing products. Second, the company embarked on a large research and development program to create a line of new products technologically superior to those being manufactured by Blackman. Each of these initiatives required multimillion-dollar commitments by USSC-commitments that threatened the company's steadily rising profits and Hirsch's ability to raise additional capital that USSC desper- ately needed to finance its rapid growth. Hirsch overcame the major challenges facing his company. USSC maintained its dominant position in the surgical stapling industry, while continuing to report record profits and sales each year. Ironically, those record profits and sales even- tually spelled trouble for the company. Mounting suspicion that USSC's reported operating results were too good to be true prompted the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to launch an investigation of the company's financial affairs. In 1983, the SEC leveled several charges of misconduct against key USSC officers, including Leon Hirsch. Within a short time, USSC's audit firm, Ernst & Whinney, resigned and withdrew the unqualified audit opinions it had issued on the com- pany's 1980 and 1981 financial statements. In 1985, the SEC released a report on its lengthy investigation of USSC. The SEC ruled that the company had used a "variety of manipulative devices to overstate its earnings in its 1986 and 1981 fi- nancial statements."1 (Exhibit 1 contains USSC's original balance sheets and in- come statements for the period 1979 to 1981.) To settle the SEC charges, USSC officials signed an agreement with the federal agency that forced the company to reduce its previously reported earnings by $26 million. Additionally, senior executives of USSC agreed to return to the company large bonuses they had been paid during 1980 and 1981. Hirsch alone repaid more than $300,000 to USSC. Following the signing of the agreement with the SEC, Hirsch reported that the criticism of his company and his management decisions was undeserved. Hirsch implied that cost considerations motivated him to accept the SEC sanctions: "It was our opinion that the settlement (with the SEC) was preferable to long, costly and time-consuming litigation."2 USSC'S ABUSIVE ACCOUNTING PRACTICES The enforcement release that disclosed the key findings of the SEC's investigation of USSC charged the company with several abusive accounting and financial re- porting practices. A focal point of the SEC's investigation was an elaborate scheme that USSC executives implemented to charge inventoriable production costs to a long-term asset account, molds and dies. This scheme, which required the cooperation of several of USSC's vendors, was deliberately concealed from the company's audit firm, Ernst & Whinney. The SEC investigation also revealed that USSC recorded inventory shipments to its sales force as consummated sales transactions. Until the mid-1970s, USSC had marketed its products through a network of independent dealers. Histori- cally, inventory shipments to these dealers had been treated as arm's length transactions and thus reportable as revenue. By 1980, the company marketed its products almost exclusively through a sales staff consisting of full-time employ- ees working on a commission basis. Each member of the sales staff maintained an inventory of USSC products, which they transported from client to client. In 1980 and 1981, USSC's management began intentionally shipping excessive amounts of inventory to its sales staff. A former USSC sales manager later testi- fied regarding this practice. "It was nothing to come home and find $3,000 worth of product sitting in a box on your front porch from UPS and a note saying, "We thought you needed a little more product. 4 According to the SEC, USSC's pol- icy of recognizing inventory shipments to its sales staff as consummated sales transactions inflated the company's 1980 and 1981 pre-tax profits by $1,150,000 and $750,000, respectively. The SEC also charged that USSC abused the accounting rule that permits the capitalization of legal expenditures incurred to develop and successfully defend a patent. In 1980, the company capitalized less than $1 million of such expendi- tures; the following year, that figure leaped to $5.8 million. The SEC investigation disclosed that a significant portion of the 1981 litigation expenditures stemmed from Australian lawsuits filed against Alan Blackman and his company. Because USSC did not have any registered patents in Australia, these expenditures should have been immediately charged to operations instead of being deferred in an asset account. Approximately $3.7 million of USSC's 1981 litigation expenditures involved efforts to defend the company's U.S. patents. However, USSC chose to amortize these costs over a 10-year period even though the 17-year legal life of most of the patents would expire in 1983 or 1984. USSC leased, rather than sold, many of its surgical tools. The company's ac- counting staff recorded the cost of these assets in a subsidiary fixed asset ledger, leased and loaned assets. USSC periodically retired such assets and removed their accounts from the sub-ledger. However, SEC investigators discovered that in many cases the costs associated with these assets were not removed from the sub-ledger but instead debited to the accounts of other assets still in service. In 1981, USSC also understated depreciation expense on several fixed assets by ar- bitrarily extending their useful lives and establishing salvage values for them for the first time. U.S. Surgical Corporation Consolidated Balance Sheets 1979-1981 (000s omitted) December 31, 1980 1981 1979 $ 426 36,670 $ 1,243 30,475 $ 596 22,557 Current Assets Cash Receivables (net) Inventories Finished Goods Work in Process Raw Materials 29,216 5,105 20,948 55,269 7,914 100,279 9,860 2,667 18,806 31,333 1,567 64,618 5,685 1,153 7.365 14,203 1,820 39,176 Other Current Assets Total Current Assets Property, Plant, and Equipment Land Buildings Molds and Dies Machinery and Equipment 2,502 32,416 32,082 40,227 107,227 (14,953) 92,274 14,786 $ 207,339 2,371 18,511 15,963 23,762 60,607 (9,964) 50,643 3,842 $119,103 1,027 13,019 8,777 12,362 35,185 (6,340) 28,845 2,499 $ 70,520 Allowance for Depreciation Other Assets Total Assets $ 12,278 $ 6,951 $ 6,271 1,596 724 5,673 18,675 1,685 666 5,130 14,432 401 5,145 13,413 80,642 7,466 47,569 2,956 33,497 1,384 Current Liabilities Accounts Payable Notes Payable Income Taxes Payable Current Portion of Long-Term Debt Accrued Expenses Total Current Liabilities Long-Term Debt Deferred Income Taxes Stockholders' Equity Common Stock Additional Paid-in Capital Retained Earnings Translation Allowance Deferred Compensationfrom Issuance of Restricted Stock Total Stockholders' Equity Total Liabilities and Stockholders' Equity 1,081 72,594 32,665 (1,086) 930 34,932 20,881 379 10,736 13,189 (4,698) 100,556 $207,339 (2,597) 54,146 $119,103 (2,078) 22,226 $ 70,520 U.S. Surgical Corporation Consolidated Income Statements 1979-1981 (000s omitted) For the Year Ended December 31, 1980 1979 1981 $111,800 $86,214 $ 60,876 Net Sales Costs and Expenses Cost of Products Sold Selling, General, and Administrative Interest 47.983 45,015 5,898 98,896 12,904 32,300 37,740 4,063 74,103 12,111 25,659 23,935 3,403 52,997 7,879 Income Before Income Taxes Income Taxes Federal and Foreign State and Local 795 325 1,120 $ 11,784 3,406 820 4,226 $ 7,885 2,279 471 2,750 $ 5,129 Net Income Net Income per common share and common share equivalent $1.13 $.89 $.68 Average number of common shares and common share equivalents outstanding 1981 10,403,392 1980 8,816,986 1979 7,555,710 Included in these amounts are the following research and development expenses: 1981- $1,337, 1980-$3,020, 1979$2,289

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts