Question: Cavanaughs Kubbs - Operations Management Case Study by Ivey Publications John Cavanaugh, a carpenter based in London, Ontario, was trying to decide how to arrange

Cavanaughs Kubbs - Operations Management Case Study by Ivey Publications

John Cavanaugh, a carpenter based in London, Ontario, was trying to decide how to arrange the production process for manufacturing the increasingly popular Swedish lawn game, known as "kubb." As both a woodworker and kubb enthusiast, Cavanaugh had handcrafted several game sets for his friends and family, and he now wanted to start a part-time business venture manufacturing and selling his kubbs to the general public. Cavanaugh had to increase production efficiency to accommodate the growing interest in his unique game piece design, but he was unsure how best to arrange the production process. He may have to invest in new equipment, hire part-time labor or purchase pre-made supplies, but he knew that, regardless of the decisions, he would have to change the current process to meet the upcoming year's estimated demand for kubb sets.

JOHN CAVANAUGH

Cavanaugh's educational background was in business and architectural design. Before moving to the construction trade, he had enjoyed a successful career in sales and distribution in the technology and

packaged goods industries. Cavanaugh's grandfather and uncle were both accomplished furniture makers

and finish carpenters, leading Cavanaugh to believe that woodworking was in his blood. After 10 years in

the corporate world, he chose to pursue his passion - custom carpentry. Cavanaugh began as a self-taught

carpenter with no formal training in the industry. He worked with several commercial and residential

construction firms throughout Ontario and the United States, where he acquired his skills on the job,

working under a number of experienced and highly talented tradespeople. He then completed a carpentry

apprenticeship under the Interprovincial Standards Red Seal Program. Cavanaugh had spent his last 10

years working full-time as a carpenter for a well-known custom design and renovations firm in

Southwestern Ontario, specializing in high-end commercial and residential projects.

Although Cavanaugh enjoyed working for the custom design and renovation firm, his true passion was in

fine carpentry and woodworking. In his spare time, Cavanaugh built custom furniture and often gave his

pieces as gifts to friends and family. Word-of-mouth referrals spread, and soon there was enough demand

for Cavanaugh to convert his home's standalone triple-car garage into a large wood shop and to carry on a

small side business selling made-to-order customer furniture and home dcor accessories to supplement his income and to help refine his craft as a custom carpenter.

.

One weekend, Cavanaugh was camping with family and friends, enjoying a match of outdoor soccer, when the ball rolled onto an adjacent campground and interrupted another family's game. Cavanaugh did not recognize the game that the family was playing and, as he went to retrieve his soccer ball, he asked the group about the game. The family was eager to tell him all about it but, rather than describe the game, they insisted that he and his family join in and experience it for themselves. Cavanaugh and his family played with their newfound friends for over nine hours that day and instantly became addicted to the outdoor lawn game they learned was called "kubb."

KUBB History

The game "kubb" (typically, pronounced "koob" in English) was an outdoor lawn game best described as a combination of bowling and horseshoes. Two teams composed of two to 20 participants took turns playing against each other with the objective of knocking over the other team's set-up of wooden blocks, known as "kubbs," by throwing cylindrical batons at them. The ultimate goal was to be the first team to knock over the single "king" kubb. Although rules varied from country to country and region to region, popular belief held that the official game originated on Gotland Island in Sweden several centuries ago.

Game Pieces and Set-Up

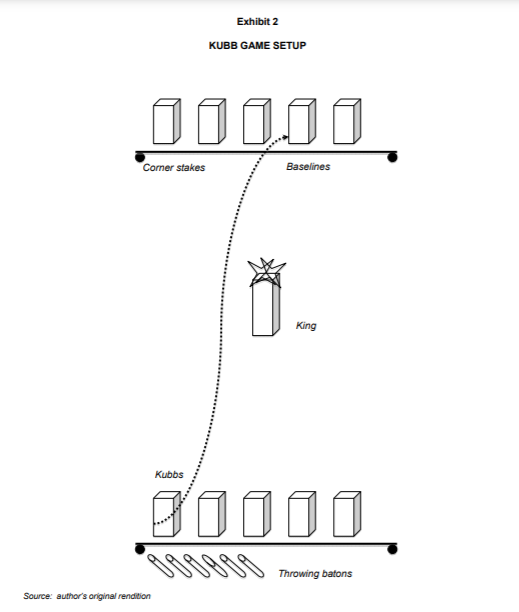

Kubb was typically played on a game pitch2 measuring five metres by eight metres in dimension, marked

by stakes driven into the ground at the four corners of the playing area, designating the narrow ends as

each team's "baseline." Although the game was generally played on grass, other surfaces such as gravel,

dirt, sand, concrete, snow and ice were also suitable as long as the playing pitch was level. There was also

considerable variation in the design of the 21 game pieces; however, each was usually made of pine or

hardwood such as ash, oak, maple and walnut and consisted of: one "king," measuring nine centimetres by nine centimeters square and 30 centimetres high, ten "kubbs" (rectangular blocks) approximately seven centimetres by seven centimetres square and 15 centimetres high, six cylindrical throwing batons, each 44 millimetres in diameter and 30 centimetres long, and four stakes used to designate the corners of the playing pitch, measuring two centimetres by two centimetres by 30 centimetres. (See Exhibit 1 for a

typical kubb set).

The Game

The ten kubbs were set up across each baseline, five per side, and players stood behind their team's

respective baseline. The king was placed in the centre of the pitch, halfway between the two baselines.

There were then two phases for each team's turn. In the first phase, team A threw the six batons from their baseline at their opponent's lined-up kubbs (called baseline kubbs). Throws were to be under-handed, and batons were spun end over end. Any kubbs that were successfully knocked down by team A were then thrown by team B onto team A's half of the pitch and placed upright. These newly thrown kubbs were called field kubbs. Play then changed hands, and team B threw the six batons at Team A's kubbs, but had to first knock down any standing field kubbs just placed in the previous round. Again, kubbs that were knocked down by Team B were thrown back over onto the opposite half of the field and then placed upright. If either team left field kubbs standing after their six batons had been thrown, the kubb closest tothe king now represented that side's baseline, and throwers stepped up to that spot to throw at their opponent's kubbs. Play continued in this fashion until one of the teams knocked down all apposing3 field and baseline kubbs, giving that team the right to now attempt to topple the king kubb. During this second phase of the game, if a thrower successfully toppled the king, the thrower's team would be declared the winner. However, if at any time during the entire game the king was knocked down by accident, the offending team would immediately lose the game. (See Exhibit 2 for diagrams of typical kubb play). For informal play between participants of widely differing abilities, such as adults and children, it was permissible to shorten the playing field on the child's opponent's side, making it easier for the child to hit the kubbs. It was also permissible to move the king closer to the child's baseline. Alternatively, one team could be granted more throwing batons than the other, giving that team an increased chance of toppling more kubbs each round.

1 The information represented in this section came largely from material accessed from the Kubb World Championship

homepage at www.vmkubb.com/index.asp, accessed February 2010.

2 A game pitch is a designated area marked out for a game or sport.

Popularity

Game pieces were widely available in Nordic countries but elsewhere the game was not well known, so

most purchases were made via Internet retailers. However, over time, kubb continued to gain international

interest, and an annual World Championship had been held on Gotland Island, Sweden, since 1995. Small-scale tournaments were also becoming increasingly popular in Canada and the United States on college campuses, in community centres and at other outdoor recreational facilities such as campgrounds and beaches.

THE PRODUCT

When he was first introduced to kubb on his family's camping trip, Cavanaugh enjoyed the game so much

that he made his own set by hand out of scrap wood and old cut-offs in his workshop. His wife then

suggested that he make more sets as Christmas and birthday gifts for their friends and family. It was not

long before Cavanaugh received calls from others requesting that he handcraft sets for them. Cavanaugh

quickly recognized a market for his handmade game sets, and he set out to refine his design to sell to the

public.

After researching the history of the kubb game, gaining a keen understanding of the rules, acquainting

himself with the benefits and drawbacks of several different kubb sets already on the market and, most

importantly, playing a lot of recreational kubb with friends and family, Cavanaugh had perfected his own

premium, handcrafted design that met his objectives for durability, style and value. His rendition, branded

Cavanaugh's Kubbs, included ten kubbs, six throwing batons, one king, four corner stakes, a wooden

carrying caddy and a set of paper-printed English/French playing instructions. Cavanaugh used ultradurable maple hardwood for the kubbs, batons and king and rough pine for the stakes and caddy. Each complete set was finished with a sealing stain or polyurethane varnish, and branded with Cavanaugh's Kubbs insignia on the playing pieces and carrying caddy. Cavanaugh began accepting orders, typically charging $130 per set and earning margins of about 60 per cent.4 With a primitive information-only website and no other formal marketing or advertising, he relied heavily on word-of-mouth referrals that recommended the premium design and handcrafted nature of his game sets. Cavanaugh generally worked on the orders 15 hours a week ? about 10 hours on weekends and five hours during the week. Cavanaugh's sister was also very creative. She had a side business selling her own handmade stained glass pieces. During the spring, summer and fall seasons, she sold her wares at various craft shows and country fairs across Ontario. For the coming year, she offered to also sell Cavanaugh's kubb game alongside her own product and was willing to lend some of her booth space and time, free of charge.

3 Apposing refers to the opposite team.

4 Material costs were estimated at 40 per cent of the $130 selling price.

CURRENT PROCESS

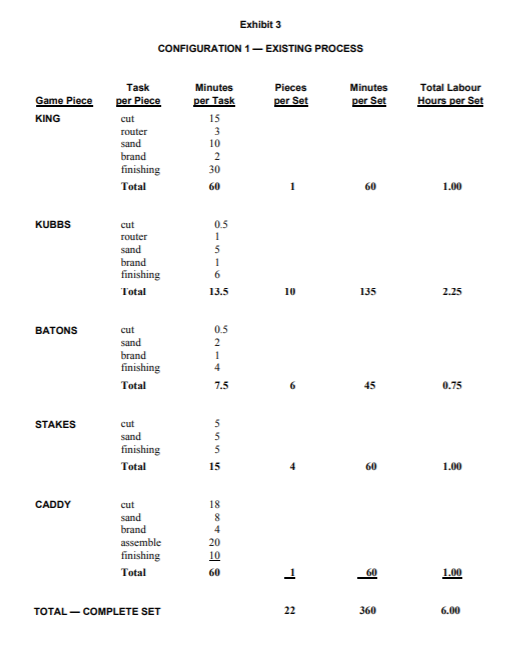

As a one-man operation, Cavanaugh's production process for crafting his kubb game was very labor

intensive. Because this process used natural materials, the times for each step varied, sometimes

considerably. Once he received a request to make a set, he usually began with the king piece, fashioning it

out of a solid square maple post and using a router and table saw to create the crown detail.5 He then cut

the ten kubbs to size from another square maple post and added a routed decorative accent to each one.

The six throwing batons were then cut from a cylindrical maple post known as doweling, and each also

received routed detailing on both ends. Finally, the four corner stakes were cut from pine cylindrical

doweling and shaped to form a point on one end.

After all 21 pieces had been cut and routed, each piece was inspected and modifications made where

necessary. Cavanaugh then sanded each piece to a smooth finish, performed a final inspection, applied the

customer's desired finishing stain color or sealing varnish and branded the bottoms of each playing piece

with his Cavanaugh's Kubbs insignia using an electric branding iron to burn his logo into the wood. While he waited for the pieces to dry after applying the finishing stain or varnish applications, Cavanaugh built the carrying caddy, rustic in appearance, out of rough pine planks, also following the same cut, router, sand finish and branding steps. When all game pieces were ready, he packed them into the caddy along with a set of printed playing instructions. Arrangements were then made for the recipient of the kubb set to receive their finished product. (See Exhibit 3 for Cavanaugh's current production configuration).

OPTIONS FOR THE FUTURE

Hire Additional Labour

Cavanaugh's sister was concerned that under the present production process, Cavanaugh could not carry on with his full-time day job and build up enough inventory to satisfy regular customer orders as well as

purchases at the multiple craft shows he would need to supply for the April to November selling season. It

was early March, and Cavanaugh believed he would need to maintain a minimum monthly finished goods

inventory of 25 sets during the months of March to October, for a total of 200 sets, in order to meet

demand from all sources. With only a 30-week window for this production, Cavanaugh's sister suggested

that he look into hiring extra help to assist with producing this inventory. He had worked with some

younger aspiring woodworkers that he had hired to help him with previous side projects, and Cavanaugh

thought they would be well suited for this part-time opportunity. He thought $70 per completed set would

be fair compensation for their time. Cavanaugh would supply all materials and tools and anyone he hired

would use his workshop in the evenings and/or on weekends.

5 Cavanaugh used a number of common power and hand woodworking tools. A table saw was used to make straight or

angled cuts along or across a board. A table saw consisted of a circular saw blade protruding through a slot in a metal

table. A router had many applications and was commonly used to create decorative effects by cutting out the face or edge

of a piece of wood.

Production Blitz

Organize Production by Game Piece

Cavanaugh was also considering an alternative way of organizing the production process. Rather than

building up and replenishing his inventory over the eight-month selling period as needed, he wondered if it would be more efficient and effective to schedule one single production blitz whereby all 200 game sets

would be made within a specific time period. His workshop was large enough to house the necessary

work-in-process, completed inventory and the five extra workers he would need to execute this option.

In this scenario, Cavanaugh envisioned five stations, just as his current process had, with one worker at

each station. All would work simultaneously, and each worker would be responsible for producing one

component (kings, kubbs, batons, corner stakes and caddies) of the game set. Cavanaugh believed that five days of consecutive work was the maximum time for an intense production blitz of this nature.

Consequently, he estimated a payment to each of the workers of $14 per hour would be adequate compensation for working alongside each other for five straight 10-hour workdays.6 He also thought that

his time would be best spent overseeing production and ensuring things were moving smoothly rather than actually building any of the game pieces himself.

6 Excluding unpaid breaks.

Organize Production by Task

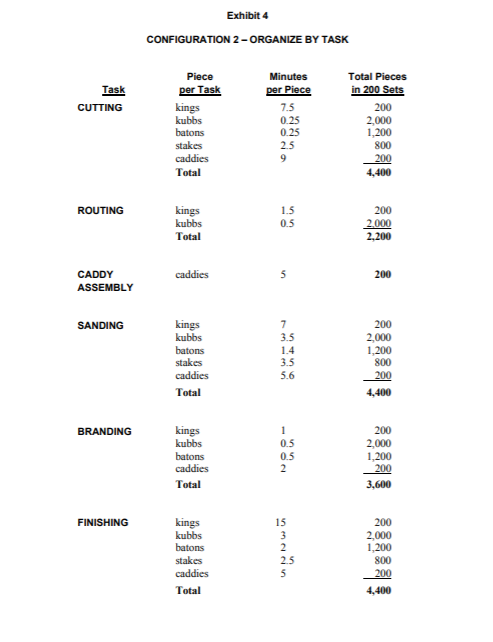

Intrigued by the option of spending a scheduled amount of dedicated time to completing the game sets in

advance, Cavanaugh had come up with another way to arrange the process for a five-day production blitz.

Although he liked the idea of assigning workers by game piece, knowing they would likely take more pride and ownership in being responsible for making one piece for the 200 sets, rather than simply performing all the cutting or sanding required for all the pieces, he also liked the degree of specialty and proficiency the workers would gain from being assigned by task. For example, cutting all 4,400 game pieces versus cutting only 200 kings could make for a more highly efficient and effective process.

Based on tasks, Cavanaugh could set up six stations with one worker at each station. Each station would

be responsible for completing one entire task for all 200 game sets. These tasks would be cutting, routing,

sanding, caddy assembly, branding and finishing. Cavanaugh would once again assume a supervisory role

and assist the workers as needed. Under this arrangement, Cavanaugh estimated that the cutting, routing,

assembly, branding and finishing task times for each game piece would be reduced by half, and the sanding task would be reduced by 30 per cent. The timesaving would arise mainly from the reduced need to share equipment. For example, when organizing the process by game piece, all workers would be required to use Cavanaugh's table saw to perform the required cutting associated with their game piece. However, when organizing the process by task, cutting would be performed by a single worker who would be solely responsible for cutting all games pieces for all 200 sets. Cavanaugh believed that assigning workers by task instead of by game piece would thus reduce machine set-up and coordination issues, thereby translating into reduced production times overall. (See Exhibit 4 for timing estimates for each station for this process design).

Use Adhesive Decals7

Cavanaugh acknowledged that anything he could do to reduce production times would translate into more

profits, allow him to meet demand more quickly and leave room to scale production if demand increased.

This insight left Cavanaugh with an eye for creating time savings. He observed that the branding task,

where the Cavanaugh's Kubbs insignia was burned onto the kings, kubbs, batons and caddies, could be

significantly shortened if adhesive decals were applied instead of the current wood-burning technique.

Cavanaugh estimated that using decals could reduce the branding task to 15 seconds per game piece. He

had done some research and could order multi-sized, custom designed, single-colour decals for

approximately $0.20 each from an online retailer. The logo would adhere to the required game pieces

rather than be permanently burned into the wood. Cavanaugh would, however, need to purchase 5,000

decals to get the favorable per-unit cost. He wondered if the process change would be a wise move.

Purchase New Equipment

Another opportunity Cavanaugh saw for reducing production times was in the investment of additional

machinery and equipment. Further automation of his handcrafted process could result in labor savings

because of faster production times. Although Cavanaugh did not feel he could justify purchasing a largescale item such as another table saw, he was considering buying a less expensive automated paint sprayer to stain and varnish the game pieces to make the process more efficient. The current staining and

varnishing steps were done by hand with both products being applied with brushes and other hand tools.

Cavanaugh estimated that an airless paint spray gun could reduce the time to stain and varnish all 4,400

game pieces to 20 total hours and would also offer a much more consistent application and improved

finish. The suitable equipment would cost $550 but Cavanaugh wanted the investment to be paid back in less than one year. Additional electricity costs would be negligible but it was estimated that annual

maintenance and repair would be $100. Cavanaugh thought that with some of the time-savings gained

from the paint sprayer, he would have the opportunity to perform a final inspection of all the pieces to

ensure they were of premium quality and workmanship. If he did happen to find any substandard pieces

or defects, he could do the necessary rework before staining and varnishing ? the most ideal time to fix

any flaws. If flaws were found after staining and varnishing, they would be much more difficult to repair

and would likely require the pieces to undergo the finishing step again.

THE DECISION

Cavanaugh was content with his current kubb-making process but sensed that some changes might be

necessary to make production more efficient and effective if demand continued to increase. He knew that

hiring additional labor would increase production, but he was unsure which would be the best way to

incorporate this extra help into the process for an optimal outcome. Cavanaugh also knew that using

alternative supplies and equipment could be critical purchases for increasing production and improving

the quality and consistency of his game sets. He now had to decide which options to choose, how to

balance the production line, and what changes, if any, he should make to the manufacturing process.

7 A design prepared on special paper for transfer onto another surface such as wood, glass, porcelain or metal. Like a

sticker or plasticized adhesive label.

\f\f\f\f

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts