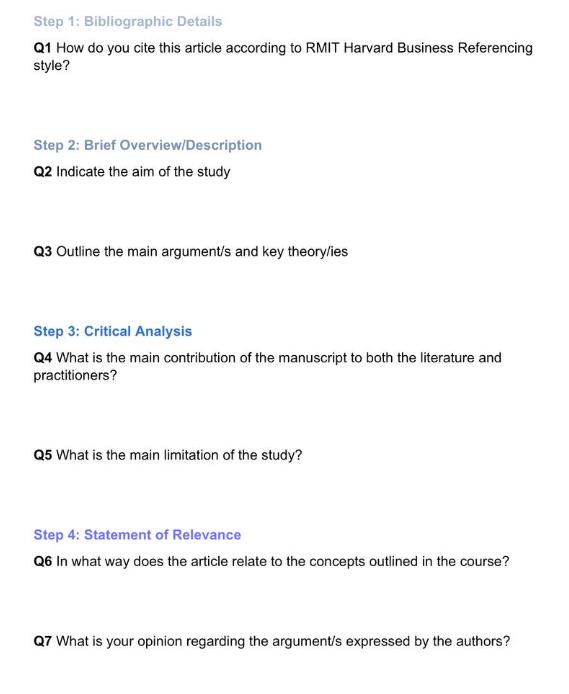

Question: Step 1: Bibliographic Details Q1 How do you cite this article according to RMIT Harvard Business Referencing style? Step 2: Brief Overview/Description Q2 Indicate