Question: Chapter 10 describes several different analysis tools. Choose two of these tools and discuss how they would be beneficial if you were trying to grow

Chapter 10 describes several different analysis tools. Choose two of these tools and discuss how they would be beneficial if you were trying to grow your company.

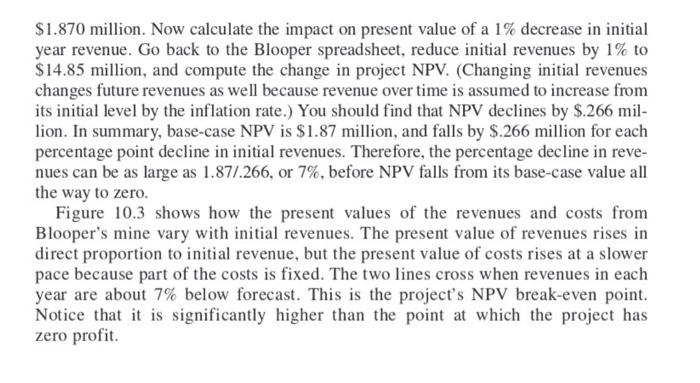

Scenario Analysis When variables are interrelated, managers often find it helpful to look at how their project would fare under different scenarios. Scenario analysis allows them to look at different but consistent combinations of variables. Forecasters generally prefer to give an estimate of revenues or costs under a particular scenario rather than to give some absolute optimistic or pessimistic value. For example, a general economic expansion might increase the market price of magnoosium but, at the same time, result in higher wages for your employees and, therefore, higher variable costs of production. When revenue and variable costs are linked, it does not make sense to do sensitivity analysis on each of them separately. Instead, you probably want to see the effect of changes in the two variables that are mutually consistent with particular economic forecasts. Other relations among your input variables may be particular to the firm. Suppose that you are worried that the company may need to construct costly levees as a protec- tion against flooding. These would require regulatory approval and involve construc- tion delays and additional costs. Output from the mine would not start for a further year. On the other hand, improved flood protection would limit the chances of future loss of production caused by extreme rainfall. In this case, it might be worth rerunning your NPV calculations to check whether the up-front flood protection measures would turn your project into a loser. estimates could be before the project begins to lose money. This exercise is known as break-even analysis. For many projects, the make-or-break variable is sales volume. Therefore, manag- ers most often focus on the break-even level of revenues. However, you might also look at other project variables, such as how high costs could be before the project goes into the red. Then, having calculated the break-even level of costs, management might say, "We really can't be sure of costs, but we can be confident that they will be less than the break-even level. It looks as if we can give the project the go-ahead." As it turns out, losing money" can be defined in more than one way. Most often, the break-even condition is defined in terms of accounting profits. More properly, however, it should be defined in terms of net present value. We will start with account- ing break-even, show that it can lead you astray, and then show how NPV break-even can be used as an alternative. NPV Break-Even Analysis A manager who calculates an accounting-based measure of break-even may be tempted to think that any project that earns more than this figure will help shareholders. But projects that merely break even on an accounting basis are really making a lossthey are failing to cover the costs of capital employed. Managers who accept such projects are not helping their shareholders. Therefore, instead of asking what sales must be to produce an accounting profit, it is more useful to focus on the point at which NPV switches from negative to positive. This is called the NPV break-even point. Because revenues are not constant, but are expected to increase over time, it makes most sense to ask what percentage shortfall in each year's revenues would push the project into a negative NPV. To find the NPV break-even point, start by looking back at Spreadsheet 10.1, which showed that when initial revenues are $15 million, NPV is $1.870 million. Now calculate the impact on present value of a 1% decrease in initial year revenue. Go back to the Blooper spreadsheet, reduce initial revenues by 1% to $14.85 million, and compute the change in project NPV. (Changing initial revenues changes future revenues as well because revenue over time is assumed to increase from its initial level by the inflation rate.) You should find that NPV declines by $.266 mil- lion. In summary, base-case NPV is $1.87 million, and falls by $.266 million for each percentage point decline in initial revenues. Therefore, the percentage decline in reve- nues can be as large as 1.877.266, or 7%, before NPV falls from its base-case value all the way to zero. Figure 10.3 shows how the present values of the revenues and costs from Blooper's mine vary with initial revenues. The present value of revenues rises in direct proportion to initial revenue, but the present value of costs rises at a slower pace because part of the costs is fixed. The two lines cross when revenues in each year are about 7% below forecast. This is the project's NPV break-even point. Notice that it is significantly higher than the point at which the project has zero profit

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts