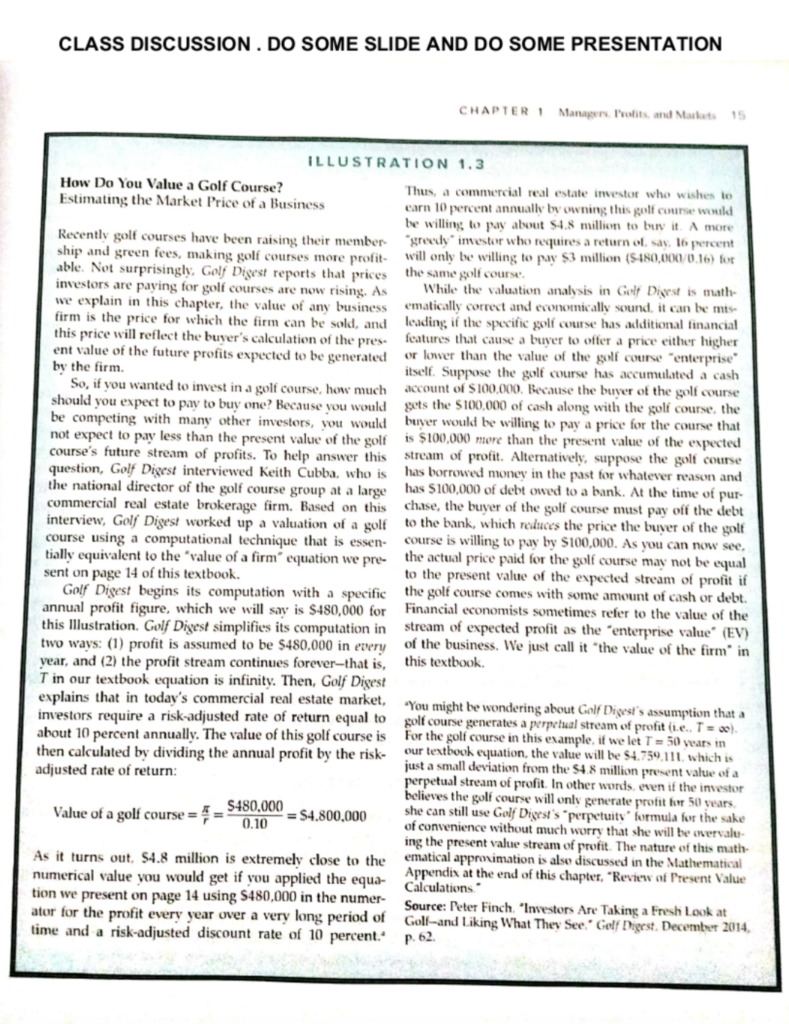

Question: CLASS DISCUSSION. DO SOME SLIDE AND DO SOME PRESENTATION CHAPTER 1 Managers, Protits and Markets 1 ILLUSTRATION 1.3 How Do You Value a Golf Course?

CLASS DISCUSSION. DO SOME SLIDE AND DO SOME PRESENTATION CHAPTER 1 Managers, Protits and Markets 1 ILLUSTRATION 1.3 How Do You Value a Golf Course? Thus, a commercial real estate investor who wishes to Estimating the Market Price of a Business carn 10 percent annually by owning this golf course would be willing to pay about $4.8 million to buy it. A more Recently golf courses have been raising their member- "greedy investor who requires a return of say, 16 percent ship and green fees, making golf courses more profit- will only be willing to pay S3 million (S-480,000/0.16) for able. Not surprisingly, Golf Digest reports that prices the same golf course. investors are paying for golf courses are now rising. As While the valuation analysis in Golf Digest is math we explain in this chapter, the value of any business ematically correct and economically sound, it can be mis firm is the price for which the firm can be sold, and leading if the specific golf course has additional financial this price will reflect the buyer's calculation of the pres features that cause a buyer to offer a price either higher ent value of the future profits expected to be generated or lower than the value of the golf course enterprise by the firm. itself. Suppose the golf course has accumulated a cash So, if you wanted to invest in a golf course, how much account of $100,000. Because the buyer of the golf course should you expect to pay to buy one? Because you would gets the $100,000 of cash along with the golf course, the be competing with many other investors, you would buyer would be willing to pay a price for the course that not expect to pay less than the present value of the golf is $100,000 more than the present value of the expected course's future stream of profits. To help answer this stream of profit. Alternatively, suppose the golf course question, Golf Digest interviewed Keith Cubba, who is has borrowed money in the past for whatever reason and the national director of the golf course group at a large has $100,000 of debt owed to a bank. At the time of pur- commercial real estate brokerage firm. Based on this chase, the buyer of the golf course must pay off the debt interview, Golf Digest worked up a valuation of a golf to the bank, which reduces the price the buyer of the golf course using a computational technique that is essen- course is willing to pay by $100,000. As you can now see, tially equivalent to the value of a firm equation we pre- the actual price paid for the golf course may not be equal sent page 14 of this textbook. to the present value of the expected stream of profit if Golf Digest begins its computation with a specific the golf course comes with some amount of cash or debt. annual profit figure, which we will say is $480,000 for Financial economists sometimes refer to the value of the this Illustration. Golf Digest simplifies its computation in stream of expected profit as the enterprise value (EV) two ways: (1) profit is assumed to be $480,000 in every of the business. We just call it "the value of the firm'in year, and (2) the profit stream continues forever-that is, this textbook. Tin our textbook equation is infinity. Then, Golf Digest explains that in today's commercial real estate market, "You might be wondering about Golf Digest's assumption that a investors require a risk-adjusted rate of return equal to golf course generates a perpetual stream of profitie. T-00) about 10 percent annually. The value of this golf course is For the golf course in this example, if we let T = 50 years in then calculated by dividing the annual profit by the risk our textbook equation, the value will be $4.759, 111, which is adjusted rate of return: just a small deviation from the 54.8 million present value of a perpetual stream of profit. In other words, even if the investor believes the golf course will only generate profit for 50 years Value of a golf course == S480,000 = $4.800.000 she can still use Golf Digest's perpetuits formula for the sake 0.10 of convenience without much worry that she will be overvale ing the present value stream of profit. The nature of this math- As it turns out $4.8 million is extremely close to the ematical approximation is also discussed in the Mathematical merical value you would get if you applied the equa- Calculations. Appendix at the end of this chapter, "Review of Present Value tion we present on page 14 using S480,000 in the numer- Source: Peter Finch 'Investors Are Taking a Fresh Look at ator for the profit every year over a very long period of Goll-and Liking What They See Gelf Digest December 2014 time and a risk-adjusted discount rate of 10 percent." P. 62 16 CHAPTER 1 The Equivalence of Value Maximization and Profit M Owners of a firm want the managers to make business decisions that will mai of the discounted expected profits in current and future periods. As a general de the value of the firm, which, as we discussed in the previous subsection, is the then, a manager maximizes the value of the firm by making decisions that maxim mizing the value of the firm are usually equivalent means to the same end: Maxima expected profit in each period. That is, single-period profit maximization and ma profit in each period will result in the maximum value of the firm, and maximizing to value of the firm requires maximizing profit in each period. Principle cost and revenue conditions in any period are independent of decisions made in the time periods, a manager wil maximize the value of a firm the present value of the firm by making decisions maximize profit in every single time period. The equivalence of single-period profit maximization and maximizing the value of the firm holds only when the revenue and cost conditions in one time period are indepen dent of revenue and costs in future time periods. When today's decisions affect profits in future time periods, price or output decisions that maximize profit in each single time period will not maximize the value of the firm. Two examples of these kinds of ods by producing more output in earlier periods-a case of learning by doing-and (2) current production has the effect of increasing cost in the future-as in extractive industries such as mining and oil production. Thus, if increasing current output has a positive effect on future revenue and profit, a value-maximizing manager selects as output level that is greater than the level that maximizes profit in a single time period Alternatively, if current production has the effect of increasing cost in the future, may imizing the value of the firm requires a lower current output than maximizing single period profit. Despite these examples of inconsistencies between the two types of maximization, i is generally the case that there is little difference between the conclusions of single-period profit maximization (the topic of most of this text) and present value maximization Thus, single-period profit maximization is generally the rule for managers to follow when trying to maximize the value of a firm. Now try Technical Problem 4 Some Common Mistakes Managers Make Taking a course in managerial economics is certainly not a requirement for making successful business decisions. Everyone can name some extraordinarily astute busi- ness managers who succeeded in creating and running very profitable firms with little or no formal education in business or economics. Taking this course will not guarare tee your success either. Plenty of managers with MBA degrees took courses in mana gerial economics but nonetheless failed sensationally and ended up getting firede replaced in hostile takeovers by more profitably managed firms. We firmly believe common mistakes that have led other managers to fail. As you progress through this CHAPTER 1 Managers, Profits, and Market 17 book, we will draw your attention at various points along the way to a number of com mon pitfalls, misconceptions, and even mistakes that real-world managers would do well to avoid Although it is too soon for us to demonstrate or prove that certain practices can reduce profit and possibly create losses in some cases-this is only Chapter 1!- we can nonetheless give you a preview of several of the more common mistakes that you will learn to avoid in later chapters. Some of the terms in this brief preview might be unclear to you now, but you can be sure that we will carefully explain things later in the text Never increase output simply to reduce average costs Sometimes managers get confused about the role of average or unit cost in decision making. For example, a firm incurs total costs of $100 to produce 20 units. The average or unit cost is $5 for cach of the 20 units. Managers may believe, incorrectly, if they can increase output and cause average cost to fall, then profit must rise by expanding production. Profit might rise, fall, or stay the same, and the actual change in profit has nothing to do with falling average costs. As you will learn in Chapter 8, producing and selling more units in the short run can indeed cause unit or average costs to fall as fixed costs of production are spread over a greater number of units. As you will learn in Chapter 9, increasing output in the long run causes average cost to fall when economies of scale are present. However, profit-maximizing firms should never increase production levels simply because aver- age costs can be reduced. As we will show you, it is the marginal cost of production- the increment to total cost of producing an extra unit--that matters in decision making. Consequently, a manager who increases or decreases production to reduce unit costs will usually miss the profit-maximizing output level. Quite simply, output or sales expansion decisions should never be made on the basis of what happens to average costs. Pursuit of market share usually reduces profit Many managers misunderstand the role market share plays in determining profitability. Simply gaining market share does not create higher profits. In many situations, if managers add market share by cutting price, the firm's profit actually falls. Illustration 1.4 examines some empirical studies of managers who pursued market share while ignoring profit. You will learn in Chapters 11 and 12 that the best general advice is to ignore market share in busi- ness decision making. We should mention here an important, although rather rare, exception to this rule that will be examined more carefully in Chapter 12: the value of market share when network effects are present. Network effects arise when the value each consumer places on your product depends on the number of other consumers who also buy your product. Suppose consumers highly value your good because a large number of other consumers also buy your good. Under these circumstances, grabbing market share faster than your rivals could give you a dominant position in the market, as consumers switch to your product away from sellers with small market shares. Failing to capture substantial market share might even threaten your long-run survival in the market. As