Coral Divers Resort Jonathon Greywell locked the door on the equipment shed and began walking back along

Question:

Coral Divers Resort

Jonathon Greywell locked the door on the equipment shed and began walking back along the boat dock to his office. He was thinking about the matters that had weighed heavily on his mind during the last few months. Over the years, Greywell had established a solid reputation for the Coral Divers Resort as a safe and knowledgeable scuba diving resort that offered not only diving but also a beachfront location. Because Coral Divers Resort was a small but well-regarded, all-around dive resort in the Bahamas, many divers had come to prefer Greywell's resort to the other crowded tourist resorts in the Caribbean.

However, over the last three years, revenues had declined; for 2008, bookings were flat for the first half of the year. Greywell felt he needed to do something to increase business before the situation worsened. He wondered whether he should add some specialized features to the resort to help distinguish it from the competition. One approach would be to focus on family outings.

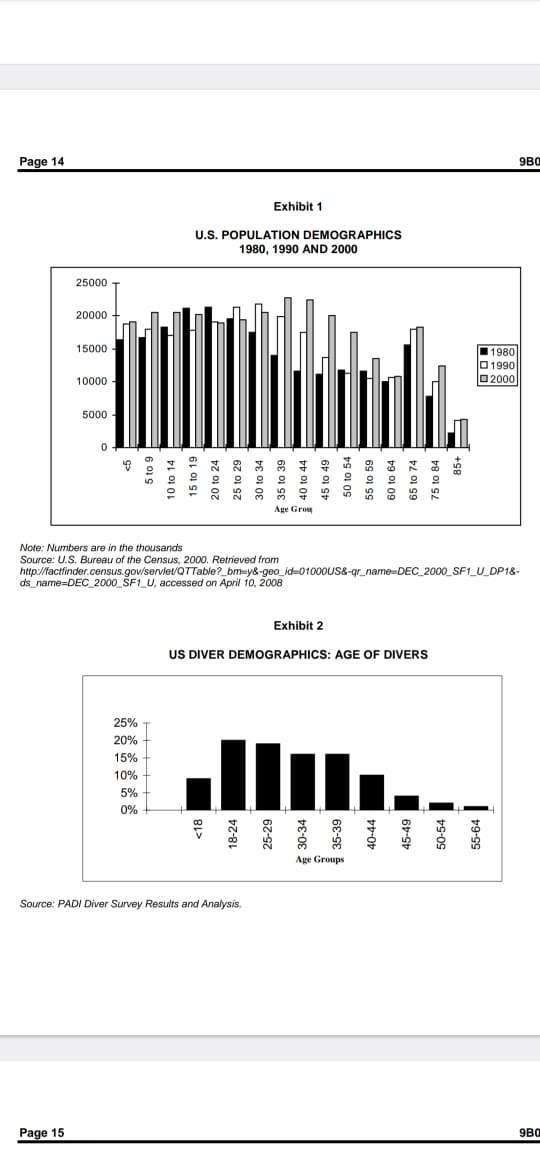

Rascals in Paradise (Rascals), a travel company that specialized in family diving vacations, had offered to help him convert his resort to specialize in family diving vacations. Rascals had shown him the industry indicating that families were a growing market segment (see Exhibit 1) and suggested the changes that would need to be made at the resort. Rascals had even offered to create children's menus and to show the cook how to prepare the meals.

Another potential strategy for the Coral Divers Resort was to focus on adventure diving. Other resort operators in the Bahamas were offering adventure-oriented deep-depth dives, shark dives and night dives.

The basic ingredients for adventure diving (i.e., reef sharks in the waters near New Providence and famous deep-water coral walls) were already in place. However, either of these strategies, creating a family vacation resort or an adventure diving resort, would require changes and additions to the current operations. Greywell was not sure whether any of the changes was worth the time and investment or whether he should instead try to improve on what he was already doing.

A final option, and one that he had only recently considered, was to leave New Providence and relocate elsewhere. At issue here was how much he might be able to recover if he sold Coral Divers Resort and whether better opportunities existed elsewhere in the Bahamas or aroundtheCaribbean.

SCUBA DIVING INDUSTRY OVERVIEW

Skin diving was an underwater activity of ancient origin in which a diver swam freely, unencumbered by lines or air hoses. Modern skin divers used three pieces of basic equipment: a face mask for vision, webbed rubber fins for propulsion and a snorkel tube for breathing just below the water's surface. The snorkel was a J-shaped plastic tube fitted with a mouthpiece. When the opening of the snorkel was above water, a diver was able to breathe. When diving to greater depths, divers needed to hold their breath; otherwise, water entered the mouth through the snorkel.

Scuba diving provided divers with the gift of time to relax and explore the underwater world without surfacing for their next breath. Scuba was an acronym for self-contained underwater breathing apparatus.

Although attempts to perfect this type of apparatus dated from the early 20th century, it was not until 1943 that the most famous scuba, or Aqualung, was invented by the Frenchmen Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Emil Gagnan. The Aqualung made recreational diving possible for millions of non-professional divers.

Although some specially trained commercial scuba divers descended below 100 meters (328 feet) for various kinds of work, recreational divers never descended below a depth of 40 meters (130 feet) because of the increased risk of nitrogen narcosis, an oxygen toxicity that causes blackouts and convulsions.

The scuba diver wore a tank that carried a supply of pressurized breathing gas, either air or a mixture of oxygen and other gases. The heart of the breathing apparatus was the breathing regulator and the pressure-reducing mechanisms that delivered gas to the diver on each inhalation. In the common scuba used in recreational diving, the breathing medium was air. As the diver inhaled, a slight negative pressure occurred in the mouthpiece, prompting the opening of the valve that delivers the air. When the diver stopped inhaling, the valve closed, and a one-way valve allowed the exhaled breath to escape as bubbles into the water. By using a tank and regulator, a diver could make longer and deeper dives and still breathe comfortably.

Along with scuba gear and its tanks of compressed breathing gases, the scuba diver's essential equipment included a soft rubber mask with a large faceplate; long, flexible swimming flippers for the feet; a buoyancy compensator device (known as a BC or BCD); a weight belt; a waterproof watch; a wrist compass and a diver's knife. For protection from colder water, neoprene-coated foam rubber wet suits were typically worn.

Certification Organizations

Several international and domestic organizations trained and certified scuba divers. The most well-known organizations were PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors), NAUI (National Association of Underwater Instructors), SSI (Scuba Schools International) and NASDS (National Association of Scuba Diving Schools). Of these, PADI was the largest certifying organization.

Professional Association of Diving Instructors

The Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI), founded in 1967, was the largest recreational scuba diver training organization in the world. PADI divers comprised 70 per cent of all divers. The diving certificate issued by PADI through its instructors was acknowledged worldwide, thus enabling PADI-certified divers wide access to diving expeditions, tank filling, and diving equipment rentalandpurchase. Worldwide, PADI had certified more than 16.5 million recreational divers. In 2007, PADI International issued nearly 1 million new certifications.

In addition to PADI's main headquarters in Santa Ana, California, PADI operated regional offices in Australia, Canada, Switzerland, Japan, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States. PADI offices served more than 130,000 individual professional members and more than 5,300 dive centers and resorts in more than 180 countries and territories. Translations of PADI materials were available in more than 26 languages. PADI comprised four groups: PADI Retail Association, PADI International Resort Association, professional members and PADI Alumni Association. The three association groups emphasized the "three E's" of recreational diving: education, equipment and experience. By supporting each facet, PADI provided holistic leadership to advance recreational scuba diving and snorkel swimming to equal status with other major leisure activities, while maintaining and improving the organization's excellent safety record. PADI courses ranged from entry levels (such as scuba diver and open water diver certifications) to master scuba diver certification and a range of instructor certificates. Via its affiliate, Diving Science and Technology (DSAT), PADI also offered various technical diver courses, including decompression diving, Trimix diving and gas blending for deep sea diving. In 1995, PADI founded Project AWARE to help conserve underwater environments. Project AWARE information was integrated into most courses, and divers were offered the opportunity to exchange their standard certificate for an AWARE certificate by making a donation to the program when applying for a new certificate.

National Association of Underwater Instructors

The National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI) first began operation in 1960. The organization was formed by a nationally recognized group of instructors known as the National Diving Patrol. Since its beginning, NAUI had been active worldwide, certifying sport divers in various levels of proficiency from basic skin diver to instructor. NAUI regularly conducted specialty courses for cave diving, ice diving, wreck diving, underwater navigation, and search and recovery.

Industry Demographics2

Scuba diving had grown steadily in popularity over the last 20 years. From 1989 until 2001, certifications had increased an average of 10 per cent each year; and increases had continued to be steady, despite more difficulties surrounding air travel because of the events of September 11, 2001, and the bleaching impact of climate change on coral reefs. In 2007, the total number of certified divers worldwide was estimated to be more than 22 million. The National Sporting Goods Association, which conducted an annual sports participation survey, projected the number of active divers in the United States at 2.1 million, and market Share data from resort destinations showed 1.5 million active traveling U.S.-based scuba divers, not including resort divers.

Approximately 65 per cent of the certified scuba divers were male, 35 per cent were female and about half of all scuba divers were married. Approximately 70 per cent of scuba divers were between the ages of 18 and 34, and approximately 25 per cent were between the ages of 35 and 49 (see Exhibit 2). Scuba divers were generally well educated: 80 per cent had a college education. Overwhelmingly, scuba divers were employed in professional, managerial and technical occupations and earned an average annualhousehold income of $75,000, well above the national average. Forty-five per cent of divers traveled most often with their families, and 40 per cent traveled most often with friends or informal groups.

People were attracted to scuba diving for various reasons; seeking adventure and being with nature were the two most often cited reasons (identified by more than 75 per cent of divers). Socializing, stress relief, and travel also were common motivations. Two-thirds of all divers traveled overseas on diving trips once every three years, whereas 60 per cent traveled domestically on dive trips each year. On average, divers spent $2,816 on dive trips annually, with an average equipment investment of $2,300. Aside from upgrades and replacements, the equipment purchase could be considered a one-time cost. Warm-water diving locations were generally chosen two to one over cold-water diving sites. Outside of the continental United States, the top three diving destinations were Cozumel in Mexico, the Cayman Islands and the Bahamas.

According to a consumer survey, the strongest feelings that divers associated with their scuba diving experiences were excitement and peacefulness. In a recent survey, these two themes drew an equal number of responses; however, the two responses had very distinct differences. The experience of excitement suggested a need for stimulation, whereas experience of peacefulness suggested relaxation and escape. Visual gratification (beauty) was another strong motivation for divers, as were the feelings of freedom, weightlessness and flying.

Under PADI regulations, divers needed to be at least 10 years old to be eligible for certification by the majority of scuba training agencies. At age 10, a child could earn a junior diver certification. Divers with this certification had to meet the same standards as an open water diver but generally had to be accompanied on dives by a parent or another certified adult. At age 15, the junior diver certification could be upgraded to open water status, which required a skills review and evaluation. Youth divers required pre-dive waiver and release forms signed by a parent or guardian until they reached age 18. Recently, PADI added a so-called bubble-maker program, which allowed children as young as age 8 to start scuba diving at a maximum depth of two meters (six feet). The program was conducted by PADI instructors in sessions that typically lasted one hour, and no pre-training was required. However, few dive centers had adopted the program because of the additional investment in special child-sized equipment and the low student-to-instructor ratio, which made the program uneconomical. On the other hand, children's programs increased the family friendliness of scuba diving.

In general, most dive centers maintained a cautious approach to young divers, based on the concept of readiness to dive. An individual's readiness to dive was determined by physical, mental and emotional maturity. Physical readiness was the easiest factor to assess: Was the child large enough and strong enough to handle scuba equipment? A regular air tank and weight belt can weigh more than 40 lbs. (18 kilograms).

Mental readiness referred to whether the child had the academic background and conceptual development to understand diving physics and perform the arithmetic required for certification. The arithmetic understanding was needed to determine a diver's allowable bottom time, which required factoring in depth, number of dives and length of dives. Emotional readiness was the greatest concern. Would the junior diver accept the responsibility of being a dive buddy? Divers never dived alone, and dive buddies needed to look out for and rely on each other. Did young divers comprehend the safety rules of diving and willingly follow them? Most dive centers therefore accepted students from age 10, but the final determination of readiness to dive rested with the scuba instructor. Instructors were trained to evaluate the readiness of all students before completion of the course work and would only award a certification to those who earned it, regardlessofage.

DIVING IN THE BAHAMAS3

New Providence Island, the Bahamas New Providence Island was best known for its major population center, Nassau, a community whose early development was based on its superb natural harbor. As the capital of the Bahamas, it was the seat of government and home to 400 banks, elegant homes, ancient forts and a wide variety of duty-free shopping.

Nassau had the island's most developed tourist infrastructure exemplified by its elegant resort hotels, casinos, cabaret shows and cruise ship docks. More than two-thirds of the population of the Bahamas lived on the island of New Providence, and most of these 180,000 people lived in or near Nassau, on the northeast corner of the island.

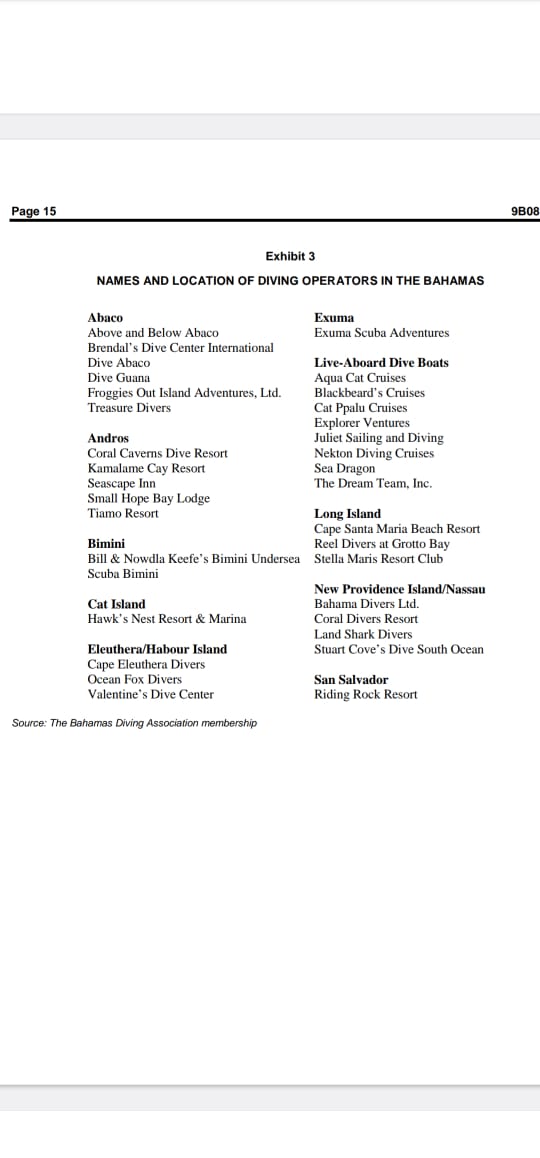

Because thousands of vacationers took resort-based diving courses (introductory scuba courses taught in resort pools), Nassau had become known as a destination for both an exploratory first dive and more advanced diving. As a result, many professional dive operations were located in the Nassau area (see Exhibit 3). Although all dive operations offered resort courses, many also offered a full menu of dive activities designed for more advanced divers. Within a 30-minute boat ride of most operations were shipwrecks, beautiful shallow reefs and huge schools of fish.

In contrast to the bustle of Nassau, the south side of New Providence Island was quieter and more laid back. Large tracts of pine trees and rolling hills dominated the central regions, while miles of white sand beach surrounded the island. At the west end of the island was Lyford Cay, an exclusive residential area.

Nearby, the Coral Harbour area offered easy access to the sea. Although golf and tennis were available, the primary attractions were the good scuba diving and the top-quality dive operators.

The southwest side of the island had been frequently used as an underwater film set. The "Bond wrecks" were popular diving destinations for divers and operators. The Vulcan Bomber used in the James Bond film Thunderball had aged into a framework draped with colorful gorgonians and sponges. The freighter,

Tears of Allah, where James Bond eluded the Tiger Shark in Never Say Never Again, remained a popular dive attraction in just 40 feet of water. The photogenic appeal of this wreck had improved with age as marine life increasingly congregated on this artificial reef.

Natural underwater attractions, such as Shark Wall and Shark Buoy, were popular dive spots. Drop-off dives, such as Tunnel Wall, featured a network of crevices and tunnels beginning in 30 feet of water and exiting along the vertical wall at 70 or 80 feet. Southwest Reef offered magnificent coral heads in only 15 to 30 feet of water, with schooling grunts, squirrelfish and barracuda. A favorite of the shallow reef areas was Goulding Cay, where Elkhorn coral reached nearly to the surface.

TYPES OF DIVING

A wide array of diving activities was available in the Bahamas, including shark dives, wreck dives, wall dives, reef dives, drift dives and night dives. Some illustrative examplesfollow.

Shark Diving

The top three operators of shark dives in the Caribbean were located in the Bahamas. Although shark diving trips varied depending on the dive operators, one common factor was shared by all shark dives in the Bahamas: the Caribbean reef shark (Carcharhinus perezi). When the dive boat reached the shark site, the sound of the motor acted as a dinner bell. Even before the divers entered the water, sharks gathered for their handouts.

Long Island in the Bahamas was the first area to promote shark feed dives on a regular basis. This method began 20 years ago and had remained relatively unchanged. The feed was conducted as a feeding frenzy.

Sharks circled as divers entered the water. After the divers positioned themselves with their backs to a coral wall, the feeder entered the water with a bucket of fish, which was placed in the sand in front of the divers, and the action developed quickly. At Walker's Cay, in Abaco, the method was similar except for the number and variety of sharks in the feed. Although Caribbean reef sharks made up the majority of sharks seen, lemon sharks, bull sharks, hammerhead sharks and other species also appeared.

The shark feed off Freeport, Grand Bahama, was an organized event in which the sharks were fed either by hand or off the point of a polespear. The divers were arranged in a semi-circle with safety divers guarding the viewers and the feeder positioned at the middle of the group. If the sharks became unruly, the food was withheld until they calmed down. The sharks then went into a regular routine of circling, taking their place in line and advancing to receive the food. Although the sharks often came within touching distance, most divers resisted the temptation to reach out.

Shark Wall, on the southwest side of New Providence, was a pristine drop-off decorated with masses of colorful sponges along the deep-water abyss known as the Tongue of the Ocean. Divers positioned themselves along sand patches among the coral heads in about 50 feet of water as Caribbean reef sharks and an occasional bull shark or lemon shark cruised mid-water in anticipation of a free handout. During the feeding period, the bait was controlled and fed from a polespear by an experienced feeder. Usually six to 12 sharks were present, ranging from four to eight feet in length. Some operators made two dives to this site, allowing divers to cruise the wall with the sharks in a more natural way before the feeding dive.

The Shark Buoy, also on the southwest side of New Providence, was tethered in 6,000 feet of water. Its floating surface mass attracted a wide variety of ocean marine life, such as dolphin fish, jacks, rainbow runners and silky sharks. The silky sharks were typically small, three to five feet long, but swarmed in schools of six to 20, with the sharks swimming up to the divemaster's hands to grab the bait.

From the operator's standpoint, the only special equipment needed for shark dives were a chain mail diving suit for the feeder's protection, feeding apparatus and intestinal fortitude. The thrill of diving among sharks was the main attraction for the divers. For the most part, the dives were safe; only the feeder took an occasional nip from an excited shark.

Recently, shark feeding had come under attack from environmentalists for causing a change in the feeding behavior of sharks, which had led to the loss of their natural fear of humans. In addition, some rare but fatal accidents had been prominently exposed through TV news channels and newspapers. For example, in 2001, Krishna Thompson, a 34-year-old New York banker, lost a leg and very nearly his life, when he was attacked just off the beach at Lucaya Golf and Beach Resort in Freeport, Grand Bahama. Thompson successfully sued the resort for failing to warn guests that local dive operators sold shark-feeding tours at sites located less than a mile from the hotel beach. In April 2002, TV shark show daredevilErichRitterwent into severe shock and nearly lost his left leg after he was bitten by a bull shark that he had attracted to shallow water with fish bait.

In spite of opposition from a small but well-funded group of U.S. dive industry insiders including PADI, DEMA, Scuba Diving magazine and Skin Diver magazine, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission banned shark feeding in 2001. However, shark feeding remained legal in the Caribbean, and despite its dangers, was on the rise. Divers participating in shark dives were required to sign waivers before the actual dive. As noted by the fine print in most life insurance and travel insurance policies, claims for scuba-related accidents were excluded.

Wreck Diving

Wreck diving was divided into three levels: non-penetration, limited penetration and full penetration. Full penetration and deep wreck diving should be attempted only by divers who have completed rigorous training and have extensive diving experience. Non-penetration wreck diving referred to recreational diving on wrecks without entering an overhead environment that prevented direct access to the surface.

Divers with open water certification were qualified for this type of diving without any further training provided they were comfortable with the diving conditions and the wreck's depth. Limited penetration wreck diving was defined as staying within ambient light and always in sight of an exit. Full penetration wreck diving involved an overhead environment away from ambient light and beyond sight of an exit.

Safely and extensively exploring the insides of a wreck involved formal training and mental strength. On this type of dive, a diver's first mistake could be a diver's last.

Wall Diving

In a few regions of the world, island chains, formed by volcanoes and coral, have been altered by movements of the earth's crustal plates. Extending approximately due east-west across the central Caribbean Sea was the boundary between the North American and Caribbean crustal plates. The shifting of these plates had created some of the most spectacular diving environments in the world, characterized by enormous cliffs, 2,000 to 6,000 feet high. At the cliffs, known as walls, divers could experience, more than in any other underwater environment, the overwhelming scale and dynamic forces that shape the ocean. On the walls, divers were most likely to experience the feeling of free motion, or flying, in boundless space. Many of the dives in the Bahamas were wall dives.

Reef Diving

Reefs generally were made up of three areas: a reef flat, a lagoon or bay, and a reef crest. The depth in the reef flat averaged only a few feet with an occasional deeper channel. The underwater life on a shallow reef flat could vary greatly in abundance and diversity within a short distance. The reef flat was generally a protected area, not exposed to strong winds or waves, making it ideal for novice or family snorkelers. The main feature distinguishing bay and lagoon environments from a reef flat was depth. Caribbean lagoons and bays could reach depths of 60 feet but many provided teeming underwater ecosystems in as little as 15 to 20 feet, making this area excellent for underwater photography and ideal for families because it was a no-decompression stop diving site. The reef's crest was the outer boundary that sheltered the bayandtheflats from the full force of the ocean's waves. Since the surging and pounding of the waves were too strong for all but the most advanced divers, most diving took place in the protected bay waters.

FAMILY DIVING RESORTS

The current average age of new divers was 36. As the median age of new divers increased, families became a rapidly growing segment of the vacation travel industry. Many parents were busy and did not spend as much time with their children as they would have preferred. Thus, many parents who dived would have liked to have a vacation that would combine diving and spending time with their children. In response to increasing numbers of parents traveling with children, resort operators had added amenities ranging from babysitting services and kids' camps to dedicated family resorts with special facilities and rates. The resort options available had greatly expanded in recent years. At all-inclusive, self-contained resorts, one price included everything: meals, accommodations, daytime and evening activities, and water sports. Many of these facilities offered special activities and facilities for children. Diving was sometimes included or available nearby.

For many divers, the important part of the trip was the quality of the diving, not the quality of the accommodations, but for divers with families, the equation changed. Children, especially younger children, could have a difficult time without a comfortable bed, a television and a DVD player, no matter how good the diving promised to be. Some resorts that were not dedicated to family vacations, made accommodations for divers with children. Condos and villas were an economical and convenient vacation option. The additional space of this type of accommodation allowed parents to bring along a babysitter, and the convenience of a kitchen made the task of feeding children simple and economical. Most diving destinations in the Bahamas, the Caribbean and the Pacific offered condo, villa and hotel-type accommodations. Some hotels organized entertaining and educational activities for children while parents engaged in their own activities.

Because the number of families vacationing together had increased, some resorts and dive operators started special promotions and programs. On Bonaire, an island in the Netherlands Antilles, August had been designated family month. During this month, the island was devoted to families, with a special welcome kit for children and island-wide activities, including eco-walks at a flamingo reserve, snorkeling lessons, and evening entertainment for all ages. In conjunction, individual resorts and restaurants offered family packages and discounts. Similarly, in Honduras, which had very good diving, a resort started a children's dolphin camp during the summer months. While diving family members were out exploring the reefs, children aged eight to 14 spent their days learning about and interacting with a resident dolphin population. The program included classroom and in-water time, horseback riding, and paddle boating.

Rascals in Paradise

One travel company, Rascals in Paradise (Rascals), specialized in family travel packages. The founders, Theresa Detchemendy and Deborah Baratta, were divers, mothers and travel agents who had developed innovative packages for diving families. According to Detchemendy, "The biggest concern for parents is their children's safety, and then what the kids will do while they're diving or enjoying an evening on the town." The Rascals staff worked with a number of family-run resorts all over the world to provide daily activities, responsible local nannies and child-safe facilities with safe balconies, playgrounds and children'spools.

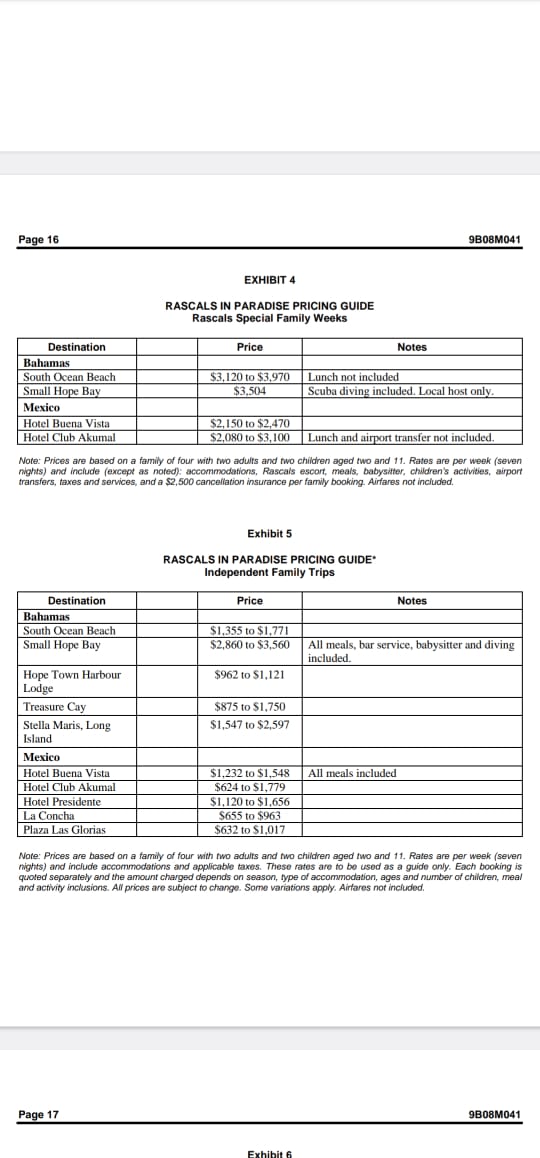

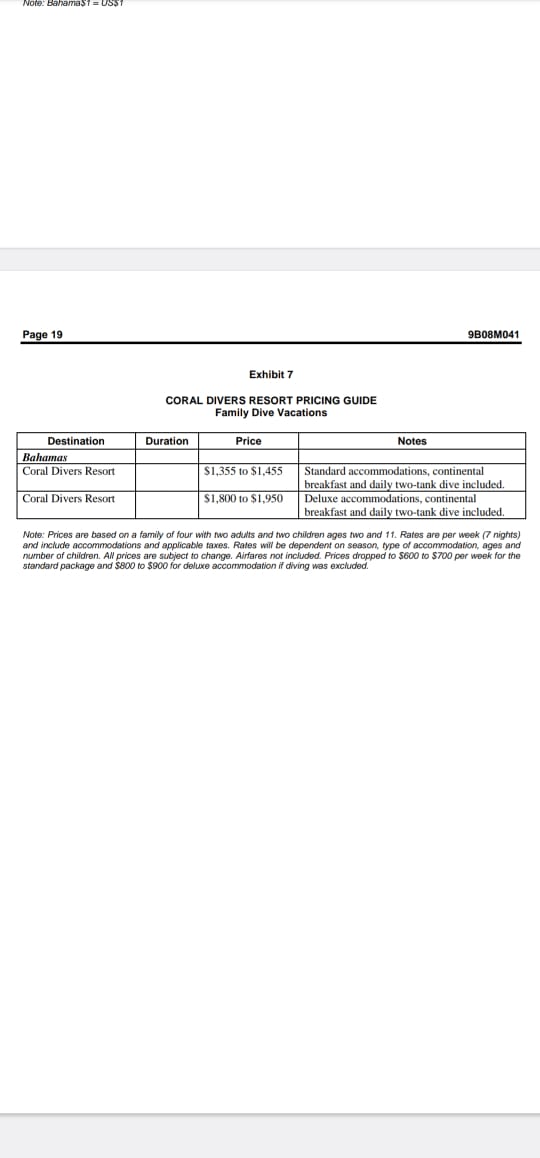

Rascals also organized family weeks at popular dive destinations in Belize, Mexico and the Cayman Islands. Family week packages accounted for more than 50 per cent of Rascals' bookings each year. On these scheduled trips, groups of three to six families shared a teacher/escort, who tailored a fun program for children and served as an activities director for the group. Rascals' special family week packages were priced based on a family of four (two adults and two children, aged two to 11) and included a teacher/escort, one babysitter for each family, children's activities, meals, airport transfers, taxes, services and cancellation insurance (see Exhibit 4) but not airfare. For example, in 2007, a seven-night family vacation at Hotel Club Akumal, on the Yucatan coast, cost US$2,080 to US$3,100 per family. Rascals also packaged independent family trips to 57 different condos, villas, resorts and hotels, which offered scuba diving. An independent family trip would not include a teacher/escort and babysitter (see Exhibit 5) and a 7-night family trip to Hotel Club Akumal would cost between US$624 and US$1,779, depending on the season and the type of room. Here also, the airfare was not included.

Rascals personally selected the resorts with which the company worked. "We try to work with small properties so our groups are pampered and looked after," said Detchemendy. "The owners are often parents and their kids are sometimes on the property. They understand the characteristics of kids." Typically, Detchemendy and Baratta visited each destination, often working with the government tourist board to identify potential properties. If the physical structure were already in place, adding the resort to the Rascals booking list was easy. If modifications were needed, then Detchemendy and Baratta met with the property's management to outline the facilities needed to include the resort in the Rascals program.

Rascals evaluated resorts according to several factors:

? Is the property friendly toward children and does it want children on the property?

? How does the property rate in terms of safety?

? What facilities does the property have? Is a separate room available that could be used as a Rascals

room?

? Does the property provide babysitting and child care by individuals who are screened and locally

known?

A successful example of this approach was Hotel Club Akumal, in Akumal, Mexico. Detchemendy and Baratta helped the resort expand its market reach by building a family-oriented resort that became part of the Rascals program. Baratta explained:

In that case, we were looking for a place close to home, with a multi-level range of accommodations, that offered something other than a beach, that was family-friendly, and not in Cancun. We found Hotel Club Akumal, but they didn't have many elements in place, so we had to work with them. We established a meal plan, an all-inclusive product, and designated activities for kids. We went into the kitchen and created a children's menu and we asked them to install a little kids' playground that's shaded.

The resort became one of Rascals' most popular family destinations.

Rascals offered two types of services to resort operators interested in creating family vacations. One was a consulting service. For a modest daily fee plus expenses, Baratta or Detchemendy, or both, would conduct an on-site assessment of the resort, which usually took one or two days. They would then provide a written report to the resort regarding needed additions or modifications to the resort to make it safe and attractive for family vacations. Physical changes might include the addition of a Rascals room and child-safe play equipment and modifications to existing buildings and structures, such as rooms, railingsanddocks,to prevent child injuries. Rascals always tried to use existing equipment or equipment available nearby. Other non-structural changes could include the addition of educational sessions, play times and other structured times for entertaining children while their parents were diving. The report also included an implementation proposal. Then, after implementation, the resort could decide whether or not to list with Rascals for bookings.

Under the second option, Rascals provided the consulting service at no charge to the resort; however, any requests for family bookings were referred to Rascals. Rascals would then list and actively promote the resort through its brochures and referrals. For resorts using the Rascals booking option, Rascals provided premiums, such as hats and T-shirts, in addition to the escorted activities. This attention to the family differentiated a Rascals resort from other resorts. Generally, companies that promoted packages received net rates from the resorts, which were 20 per cent to 50 per cent lower than the rack rates. Rascals, in turn, promoted these special packages to the travel industry in general and paid a portion of its earnings out in commissions to other travel agencies.

Rascals tried to work with its resorts to provide packaged and prepaid vacations, an approach that created a win-win situation for the resort managers and the vacationer. Packaged vacations, also known as all-inclusive vacations, followed a cruise ship approach that allowed the inclusion of many activities in the package. For example, such a package might include seven nights' lodging, all meals, babysitting, children's activities and scuba diving. This approach allowed the vacationer to know, upfront, what to expect. Moreover, the cost would be included in one set price, so that the family would not have to pay for each activity as it came along. The idea was to remove the surprises and make the stay enjoyable. The resort operator could bundle the activities together, providing more options than might otherwise be offered. As a result, the package approach was becoming popular with both resort owners and vacationers.

In its bookings, Rascals required prepayment of trips, which resulted in higher revenues for the resort since all activities were paid for in advance. Ordinarily, resorts that operated independently might require only a two- or three-night room deposit. The family would then pay for the balance of the room charge on leaving, after paying for other activities or services they used. Although vacationers might think they had a less expensive trip this way, in fact, pre-paid activities were generally cheaper than a la carte activities.

Moreover, purchasing individual activities potentially yielded lower revenues for the resort. Rascals promoted prepaid vacations as a win-win, low-stress approach to travel. Rascals had been very successful with the resorts it listed. Fifty per cent of its bookings were repeat business, and many inquiries were based on word-of-mouth referrals. All in all, Rascals provided a link to the family vacation market segment that the resort might not otherwise have access to. It was common for Rascals-listed resorts to average annual bookings of 90 per cent.

CORAL DIVERS RESORT

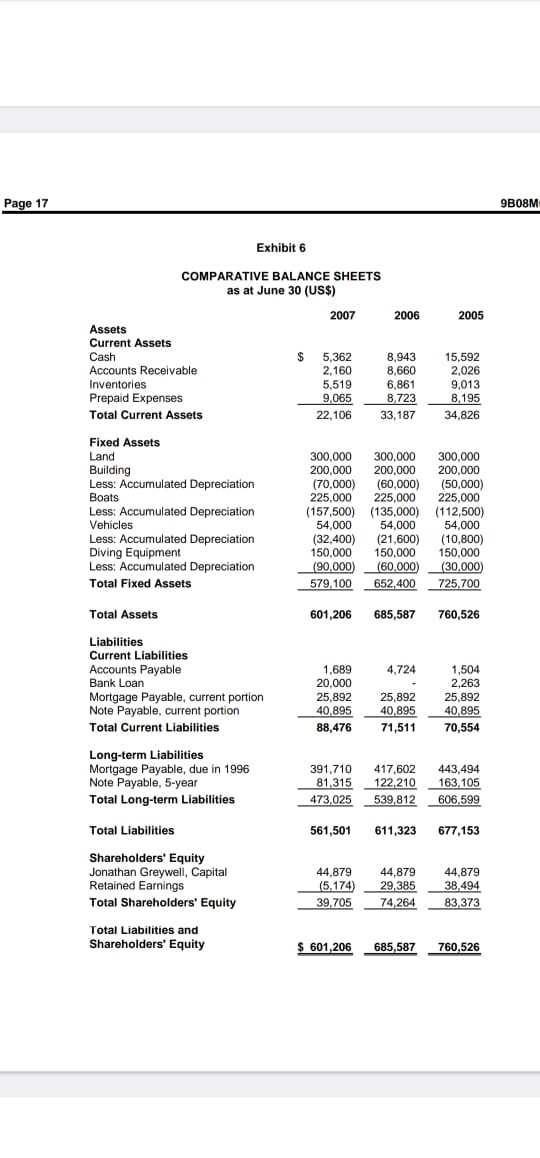

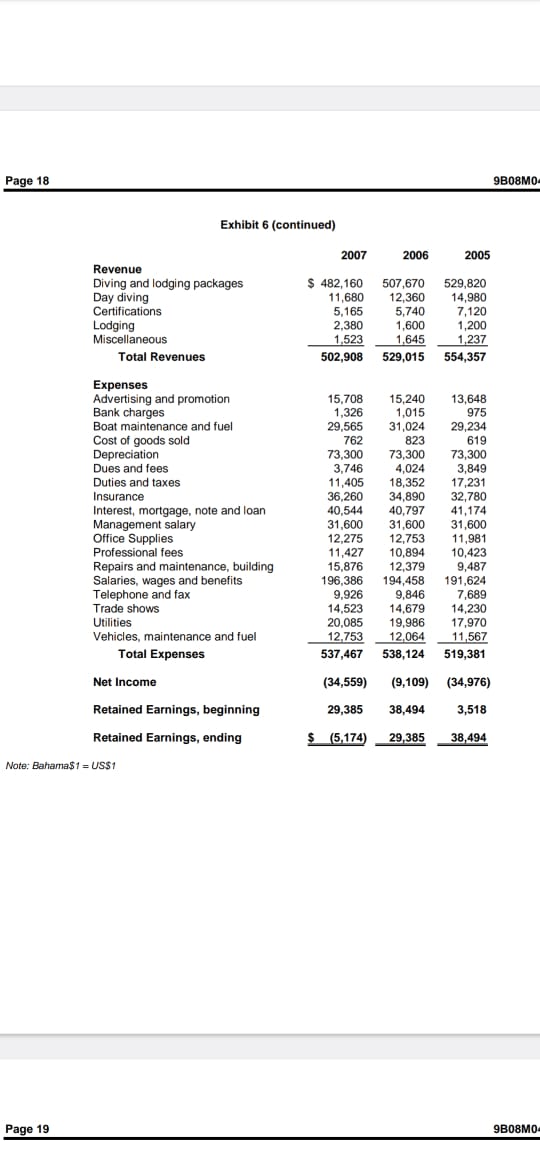

Coral Divers Resort (Coral Divers) had been in operation for 10 years. Annual revenues had reached as high as $554,000. Profits generally had been in the two per cent range, but for the past two years, the business had experienced losses. The expected turnaround in profits in 2007 had never materialized (see Exhibit 6). Although the resort was not making them rich, the business had provided an adequate income for Greywell and his wife, Margaret, and their two children, Allen, age 7, and Winifred, age 5. However, revenues had continued to decline. From talking with other operators, Greywell understood that resorts with strong identities and reputations for quality service were doing well. Greywell thought that the Coral Divers Resort had not distinguished itself in any particular aspect of divingorasaresort.

The Coral Divers Resort property was located on a deep-water channel on the southwest coast of the island of New Providence in the Bahamas. The three-acre property had beach access and featured six cottages, each with its own kitchenette, a full bath, a bedroom with two full-sized beds and a living room with two sleeper sofas. Four of the units had been upgraded with new paint, tile floors, a microwave, a color TV and a DVD player. The two other units ranged from "adequate" to "comfortable." Greywell tried to use the renovated units primarily for families and couples and housed groups of single divers in the other units (see Exhibit 7). Also on the property was a six-unit attached motel-type structure. Each of these units had two full-sized beds, a pull-out sofa, sink, a refrigerator, a microwave and a television. The resort had the space and facilities for a kitchen and dining room, but neither a kitchen nor a dining room was in use. A small family-run restaurant and bar was available within walking distance.

Greywell had three boats that could each carry from eight to 20 passengers. Two were 40-foot fiberglass V-hull boats powered by a single diesel inboard with a cruising speed of 18 knots and a protective cabin with dry storage space. The third was a 35-foot covered platform boat. Greywell also had facilities for air dispensing, equipment repair, rental and sale, and tank storage.

Coral Divers Resort, which was affiliated with PADI and NAUI, had a staff of 11, including two boat captains, two mates, a housekeeper, a groundskeeper, a person who minded the office and the store, and four scuba diving instructors. Greywell, who worked full-time at the resort, was a diving instructor certified by both PADI and NAUI. The three other diving instructors had various backgrounds: one was a former U.S. Navy SEAL working for Coral Divers as a way to gain resort experience, another was a local Bahamian whom Greywell had known for many years and the third was a Canadian who had come to the Bahamas on a winter holiday and had never left. Given the size of the operation, the staff was scheduled to provide overall coverage, with all of the staff rarely working at the same time. Greywell's wife, Margaret, worked at the business on a part-time basis, taking care of administrative activities, such as accounting and payroll. The rest of her time was spent looking after their two children and their home.

A typical diving day at Coral Divers began around 7:30 a.m. Greywell would open the office and review the activities list for the day. If any divers needed to be picked up at the resorts in Nassau or elsewhere on the island, the van driver would need to leave by 7:30 a.m. to be back at the resort for the 9 a.m. departure.

Most resort guests began to gather around the office and dock about 8:30 a.m. By 8:45 a.m., the day's captain and mate began loading the diving gear for the passengers.

The boat left at 9 a.m. for the morning dives that were usually "two tank dives," that is, two dives utilizing one tank of air each. The trip to the first dive site took 20 to 30 minutes. Once there, the captain would explain the dive, the special attractions of the dive, and tell everyone when they were expected back on board. Most dives lasted 30 to 45 minutes, depending on the depth. The deeper the dive, the faster the air consumption. On the trip down, divers were always accompanied by a divemaster, who supervised the dive. The divemaster was responsible for the safety and conduct of the divers while under water.

After the divers were back on board, the boat would move to the next site. Greywell tried to plan two dives that had sites near each other. For example, the first dive might be a wall dive in 60 feet of water, and the second might be a nearby wreck 40 feet down. The second dive would also last approximately 40 minutes.

If the dives went well, the boat would be back at the resort by noon, which allowed time for lunch and sufficient surface time for divers who might be interested in an afternoon dive. Two morning dives were part of the resort package. Whether the boat went out in the afternoon depended on the number of non-resort guest divers contracted for afternoon dives. If enough paying divers were signed up, Greywell was happy to let resort guests ride and dive free of charge. If there were not enough paying divers, no afternoon dive trips were scheduled, and the guests were on their own to swim at the beach, sightseeorjustrelax.

When space was available, non-divers (either snorkelers or bubble-watchers) could join the boat trip for a fee of $15 to $25.

Greywell's Options

Greywell's bookings ran 90 per cent of capacity during the high season (December through May) and 50 per cent of capacity during the low season (June through November). Ideally, he wanted to increase the number of bookings for the resort and dive businesses during both seasons. Adding additional diving attractions could increase both resort and dive revenues. Focusing on family vacations could increase revenues because families would probably increase the number of paying guests per room. Break-even costs were calculated based on two adults sharing a room. Children provided an additional revenue source since the cost of the room had been covered by the adults, and children under 10 incurred no diving-related costs. However, either strategy, adding adventure diving to his current general offerings or adjusting the focus of the resort to encourage family diving vacations, would require some changes and cost money. The question was whether the changes would increase revenue enough to justify the costs and effort involved.

Emphasizing family diving vacations would probably require some changes to the physical property of the resort. Four of the cottages had already been renovated. The other two also would need to be upgraded, which would cost $15,000 to $25,000 each, depending on the amenities added. The Bahamas had duties of up to 35 per cent, which caused renovation costs involving imported goods to be expensive. The attached motel-type units also would need to be refurbished at some point. The resort had the space and facilities for a kitchen and dining area, but Greywell had not done anything about opening these facilities.

The Rascals in Paradise people had offered to help set up a children's menu. He could hire a chef, prepare the meals himself or offer the concession to either the nearby restaurant or someone else. He would also need to build a children's play structure. An open area with shade trees between the office and the cottages would be ideal for a play area. Rascals would provide the teacher/escort for the family vacation groups, and it would be fairly easy to find babysitters for the children as needed. The people who lived on this part of the island were very family-oriented and would welcome the opportunity for additional income. From asking around, Greywell determined that between $5 and $10 per hour was the going rate for a sitter. Toys and other play items could be added gradually. The Rascals people had said that, once the program was in place, Greywell could expect bookings to run 90 per cent capacity annually from new and return bookings.

Although the package prices were competitive, the attraction was in group bookings and the prospect of a returning client base.

Adding adventure diving would be a relatively easy thing to do. Shark Wall and Shark Buoy were less than an hour away by boat. Both of these sites featured sharks that were already accustomed to being fed. The cost of shark food would be $10 per dive. None of Greywell's current staff was particularly excited about the prospect of adding shark feeding to their job description. But these staff could be relatively easily replaced. Greywell could probably find an experienced divemaster who would be willing to lead the shark dives. He would also have to purchase a special chain mail suit for the feeder at a cost of about $15,000.

Although few accidents occurred during shark feeds, Greywell would rather be safe than sorry. His current boats, especially the 40-footers, would be adequate for transporting divers to the sites. The other shark dive operators might not be happy about having him at the sites, but they could do little about it. Shark divers were charged a premium fee. For example, a shark dive would cost $115 for a two-tank dive, compared with $65 for a normal two-tank dive. He figured that he could add shark dives to the schedule on Wednesdays and Saturdays without taking away from regular business. Although he needed a minimum of four divers on a trip at regular rates to cover the cost of taking out the boat, 10 or 12 diverswouldbeideal.

Greywell could usually count on at least eight divers for a normal dive, but he did not know how much additional new and return business he could expect from shark diving.

A third option was for Greywell to try to improve his current operations and not add any new diving attractions, which would require him to be much more cost efficient in his operations. For example, he would have to strictly adhere to the policy of requiring a minimum number of divers per boat, and staff reductions might improve the bottom line by five per cent to 10 per cent. He would need to be very attentive to materials ordering, fuel costs and worker productivity in order to realize any gains with this approach. However, he was concerned that by continuing as he had, Coral Divers Resort would not be distinguished as unique from other resorts in the Bahamas. He did not know the long-term implications of this approach.

As Greywell reached the office, he turned to watch the sun sink into the ocean. Although it was a view he had come to love, a lingering thought was that perhaps it was time to relocate to a less crowdedlocation.

Project Management The Managerial Process

ISBN: 9781260570434

8th Edition

Authors: Eric W Larson, Clifford F. Gray