Question: Discuss the six tools of the operating manager: measurement systems, technology, organizational structure, people, leadership signals, and culture. Be prepared to discuss each in relation

Discuss the six tools of the operating manager: measurement systems, technology, organizational structure, people, leadership signals, and culture. Be prepared to discuss each in relation to the Copeland case.

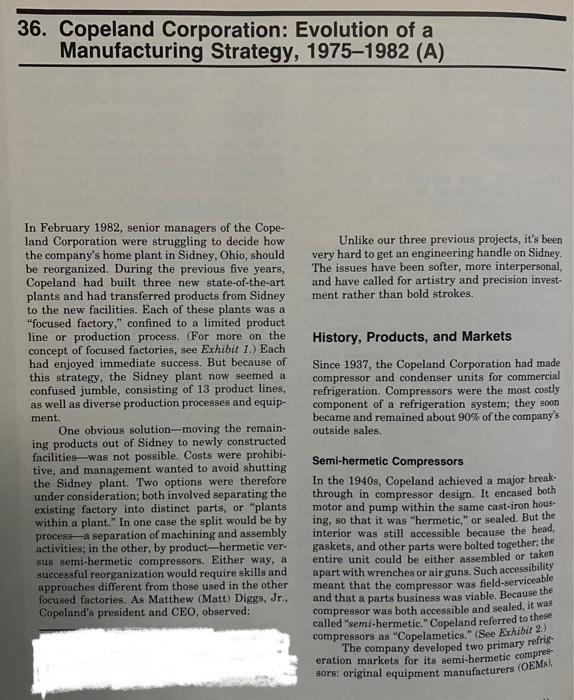

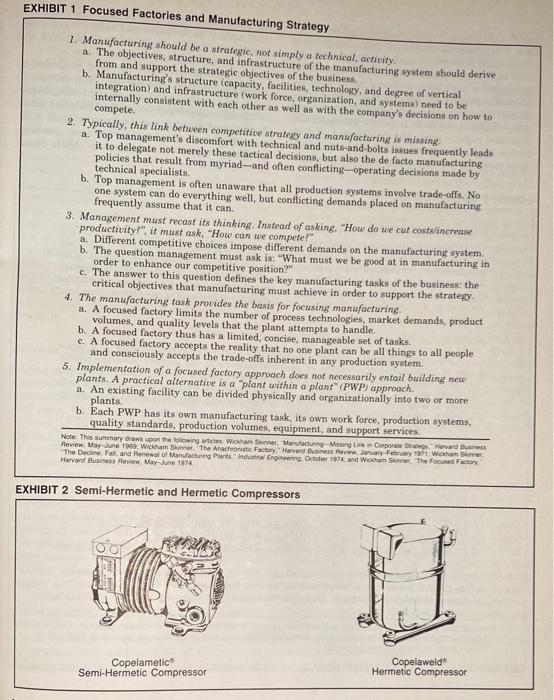

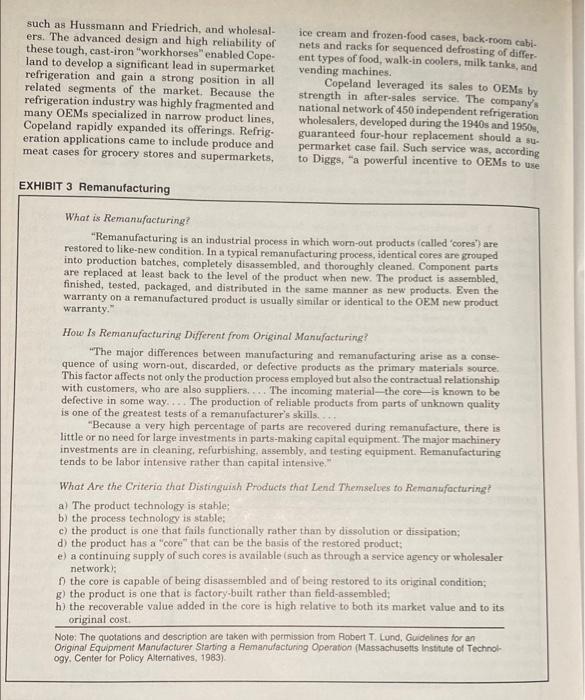

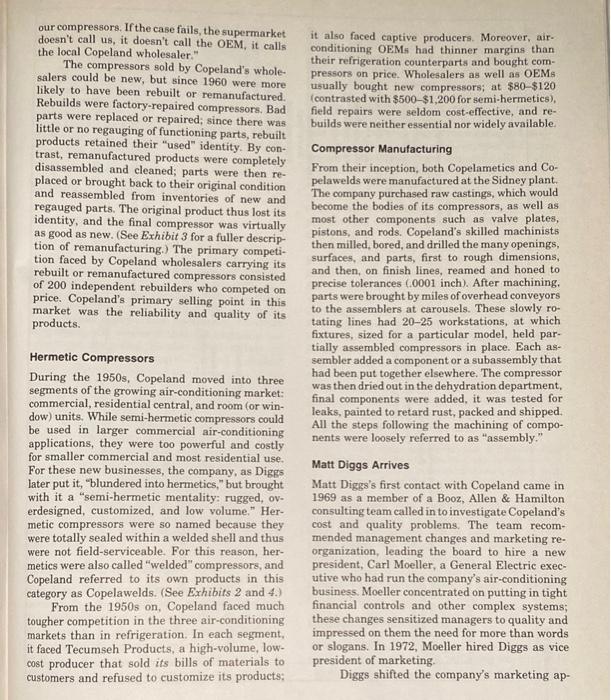

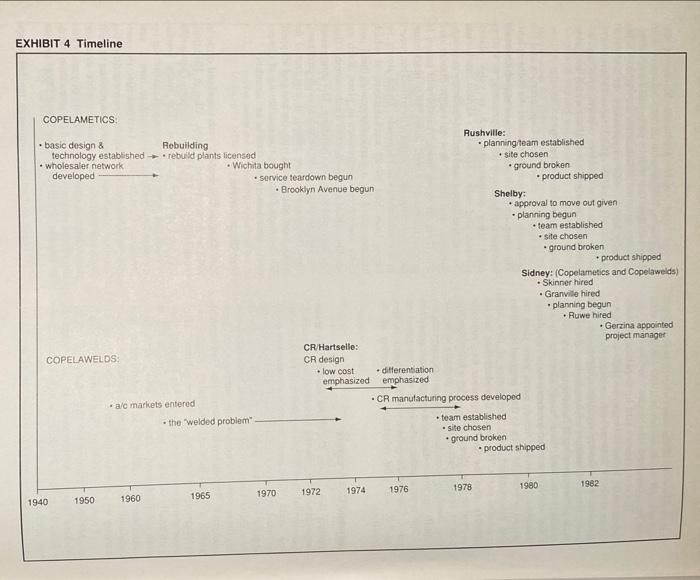

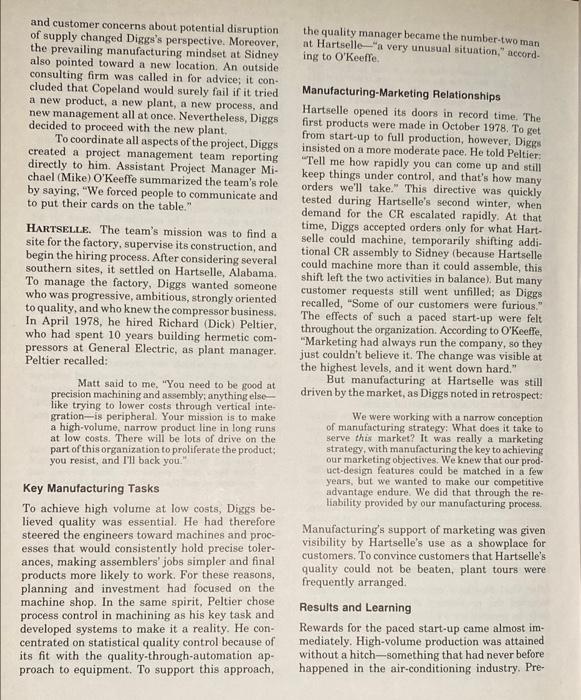

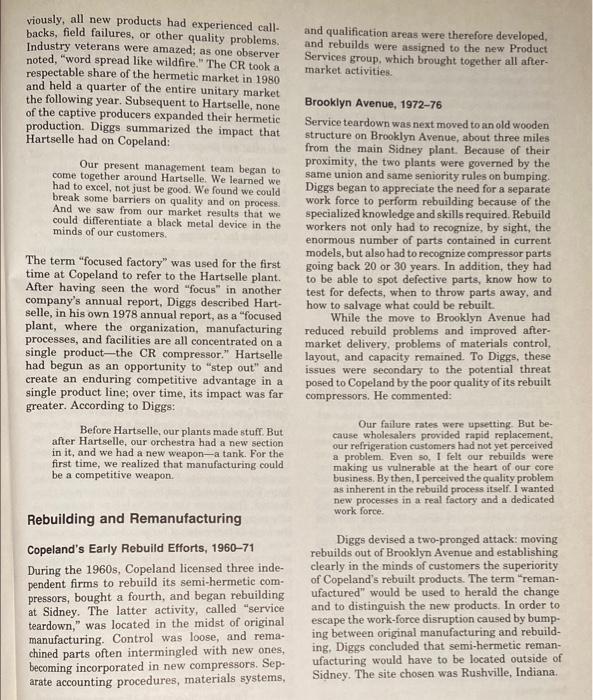

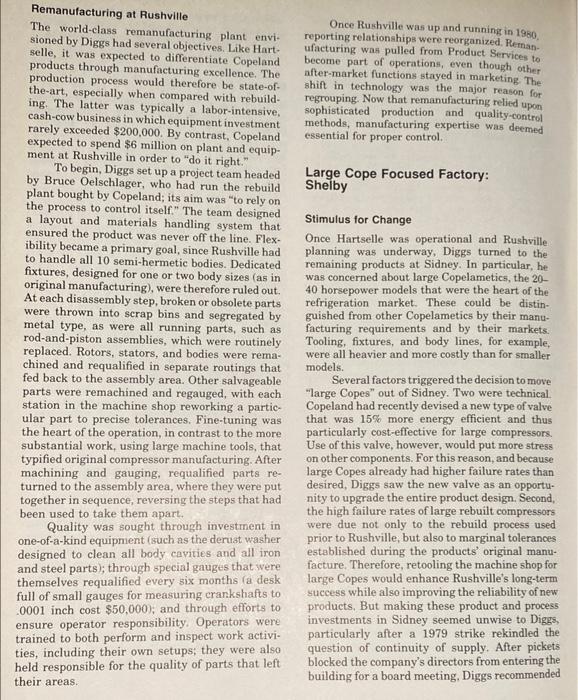

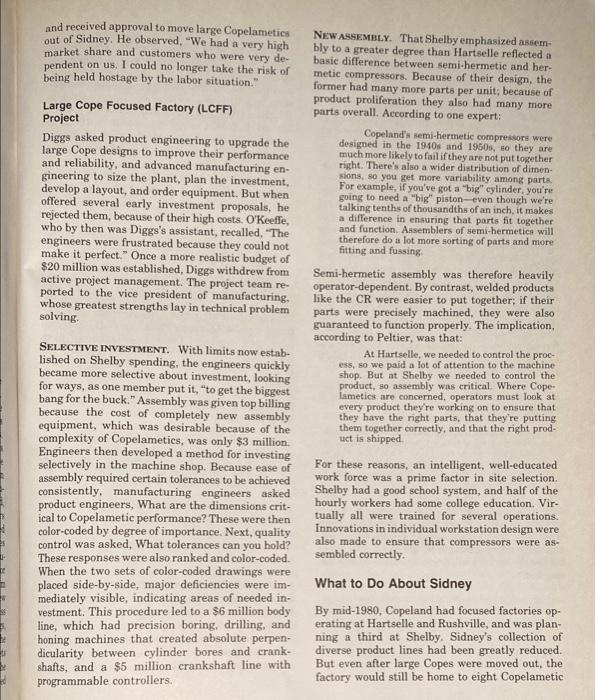

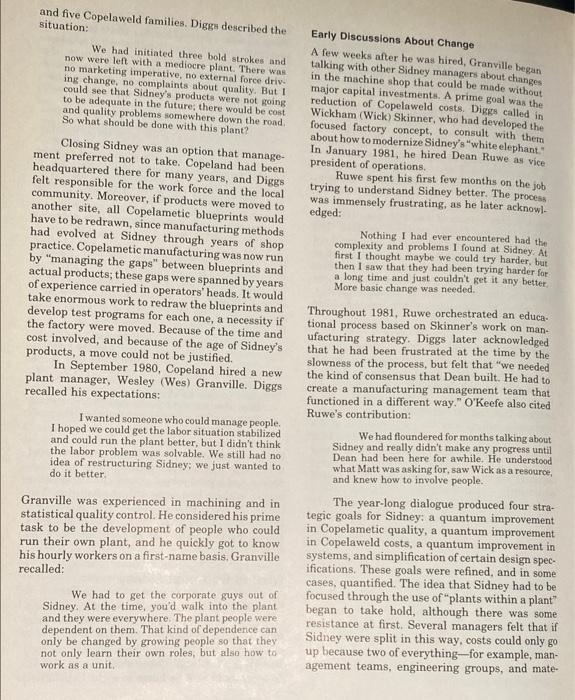

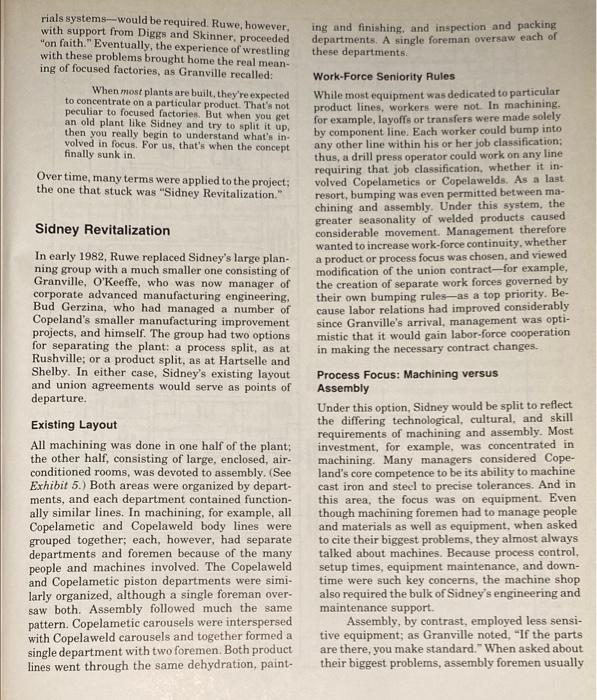

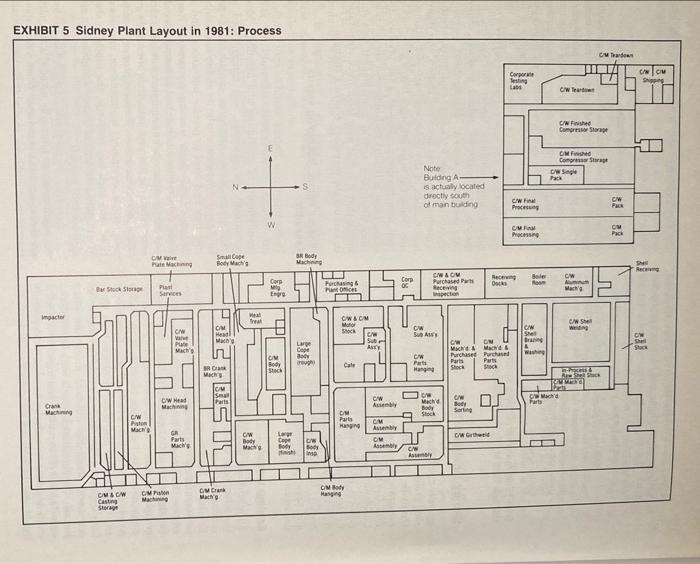

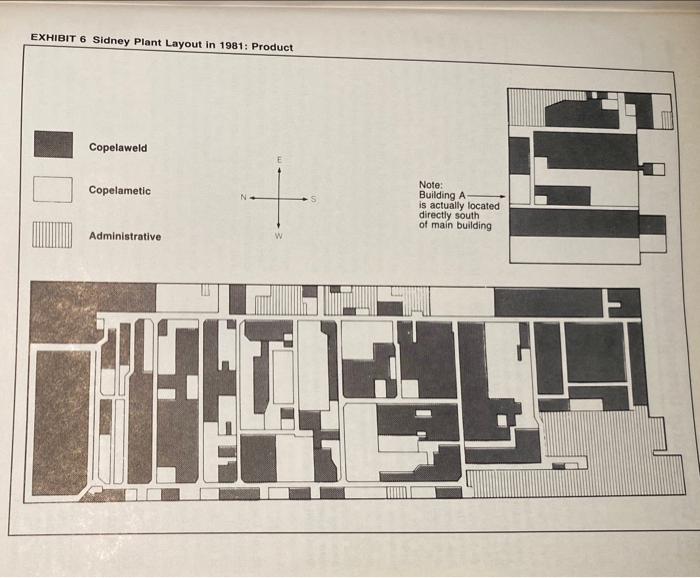

36. Copeland Corporation: Evolution of a Manufacturing Strategy, 1975-1982 (A) In February 1982, senior managers of the Cope- land Corporation were struggling to decide how the company's home plant in Sidney, Ohio, should be reorganized. During the previous five years, Copeland had built three new state-of-the-art plants and had transferred products from Sidney to the new facilities. Each of these plants was a "focused factory," confined to a limited product line or production process. (For more on the concept of focused factories, see Exhibit 1.) Each had enjoyed immediate success. But because of this strategy, the Sidney plant now seemed a confused jumble, consisting of 13 product lines, as well as diverse production processes and equip- ment. One obvious solution-moving the remain- ing products out of Sidney to newly constructed facilities was not possible. Costs were prohibi- tive, and management wanted to avoid shutting the Sidney plant. Two options were therefore under consideration; both involved separating the existing factory into distinct parts, or "plants within a plant." In one case the split would be by process-a separation of machining and assembly activities; in the other, by product-hermetic ver- sus semi-hermetic compressors. Either way, a successful reorganization would require skills and approaches different from those used in the other focused factories. As Matthew (Matt) Diggs, Jr., Copeland's president and CEO, observed: Unlike our three previous projects, it's been very hard to get an engineering handle on Sidney. The issues have been softer, more interpersonal, and have called for artistry and precision invest- ment rather than bold strokes. History, Products, and Markets Since 1937, the Copeland Corporation had made compressor and condenser units for commercial refrigeration. Compressors were the most costly component of a refrigeration system; they soon became and remained about 90% of the company's outside sales. Semi-hermetic Compressors In the 1940s, Copeland achieved a major break- through in compressor design. It encased both motor and pump within the same cast-iron hous- ing, so that it was "hermetic," or sealed. But the interior was still accessible because the head, gaskets, and other parts were bolted together; the entire unit could be either assembled or taken apart with wrenches or air guns. Such accessibility meant that the compressor was field-serviceable and that a parts business was viable. Because the compressor was both accessible and sealed, it was called "semi-hermetic." Copeland referred to these compressors as "Copelametics." (See Exhibit 2.) The company developed two primary refrig eration markets for its semi-hermetic compres sors: original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), EXHIBIT 1 Focused Factories and Manufacturing Strategy 1. Manufacturing should be a strategic, not simply a technical, activity. a. The objectives, structure, and infrastructure of the manufacturing system should derive from and support the strategic objectives of the business. b. Manufacturing's structure (capacity, facilities, technology, and degree of vertical integration) and infrastructure (work force, organization, and systems) need to be internally consistent with each other as well as with the company's decisions on how to compete. 2. Typically, this link between competitive strategy and manufacturing is missing. a. Top management's discomfort with technical and nuts-and-bolts issues frequently leads it to delegate not merely these tactical decisions, but also the de facto manufacturing policies that result from myriad-and often conflicting-operating decisions made by technical specialists. b. Top management is often unaware that all production systems involve trade-offs. No one system can do everything well, but conflicting demands placed on manufacturing frequently assume that it can. 3. Management must recast its thinking. Instead of asking, "How do we cut costs/increase productivity?", it must ask, "How can we compete?" a. Different competitive choices impose different demands on the manufacturing system. b. The question management must ask is: "What must we be good at in manufacturing in order to enhance our competitive position?" c. The answer to this question defines the key manufacturing tasks of the business: the critical objectives that manufacturing must achieve in order to support the strategy. 4. The manufacturing task provides the basis for focusing manufacturing. a. A focused factory limits the number of process technologies, market demands, product volumes, and quality levels that the plant attempts to handle. b. A focused factory thus has a limited, concise, manageable set of tasks. c. A focused factory accepts the reality that no one plant can be all things to all people and consciously accepts the trade-offs inherent in any production system. 5. Implementation of a focused factory approach does not necessarily entail building new plants. A practical alternative is a "plant within a plant" (PWP) approach. a. An existing facility can be divided physically and organizationally into two or more plants. b. Each PWP has its own manufacturing task, its own work force, production systems, quality standards, production volumes, equipment, and support services. Note: This summary draws upon the following articles Wickham Sunner, Manufacturing-Missing Link in Corporate Strategy. Harvard Business Review, May-June 1969, Wickham Skinner, The Anachronisto Factory, Harvard Business Review, January February 1971, Wickham Sunner The Decline, Fall, and Renewal of Manufacturing Plants. Industrial Engineening October 1974, and Wickham Skinner, The Focused Factory Harvard Business Review, May-June 1974 Copelaweld Hermetic Compressor EXHIBIT 2 Semi-Hermetic and Hermetic Compressors Copelametic Semi-Hermetic Compressor such as Hussmann and Friedrich, and wholesal- ers. The advanced design and high reliability of these tough, cast-iron "workhorses" enabled Cope- land to develop a significant lead in supermarket refrigeration and gain a strong position in all related segments of the market. Because the refrigeration industry was highly fragmented and many OEMs specialized in narrow product lines, Copeland rapidly expanded its offerings. Refrig- eration applications came to include produce and meat cases for grocery stores and supermarkets, EXHIBIT 3 Remanufacturing ice cream and frozen-food cases, back-room cabi- nets and racks for sequenced defrosting of differ- ent types of food, walk-in coolers, milk tanks, and vending machines. Copeland leveraged its sales to OEMs by strength in after-sales service. The company's national network of 450 independent refrigeration wholesalers, developed during the 1940s and 1950s, guaranteed four-hour replacement should a su- permarket case fail. Such service was, according to Diggs, "a powerful incentive to OEMs to use What is Remanufacturing? "Remanufacturing is an industrial process in which worn-out products (called 'cores') are restored to like-new condition. In a typical remanufacturing process, identical cores are grouped into production batches, completely disassembled, and thoroughly cleaned. Component parts are replaced at least back to the level of the product when new. The product is assembled, finished, tested, packaged, and distributed in the same manner as new products. Even the warranty on a remanufactured product is usually similar or identical to the OEM new product warranty." How Is Remanufacturing Different from Original Manufacturing? "The major differences between manufacturing and remanufacturing arise as a conse- quence of using worn-out, discarded, or defective products as the primary materials source. This factor affects not only the production process employed but also the contractual relationship with customers, who are also suppliers.... The incoming material-the core-is known to be defective in some way.... The production of reliable products from parts of unknown quality is one of the greatest tests of a remanufacturer's skills.... "Because a very high percentage of parts are recovered during remanufacture, there is little or no need for large investments in parts-making capital equipment. The major machinery investments are in cleaning, refurbishing, assembly, and testing equipment. Remanufacturing tends to be labor intensive rather than capital intensive," What Are the Criteria that Distinguish Products that Lend Themselves to Remanufacturing? a) The product technology is stable; b) the process technology is stable; c) the product is one that fails functionally rather than by dissolution or dissipation; d) the product has a "core" that can be the basis of the restored product; e) a continuing supply of such cores is available (such as through a service agency or wholesaler network); f) the core is capable of being disassembled and of being restored to its original condition; g) the product is one that is factory-built rather than field-assembled; h) the recoverable value added in the core is high relative to both its market value and to its original cost. Note: The quotations and description are taken with permission from Robert T. Lund, Guidelines for an Original Equipment Manufacturer Starting a Remanufacturing Operation (Massachusetts Institute of Technol ogy, Center for Policy Alternatives, 1983). our compressors. If the case fails, the supermarket doesn't call us, it doesn't call the OEM, it calls the local Copeland wholesaler." The compressors sold by Copeland's whole- salers could be new, but since 1960 were more likely to have been rebuilt or remanufactured. Rebuilds were factory-repaired compressors. Bad parts were replaced or repaired; since there was little or no regauging of functioning parts, rebuilt products retained their "used" identity. By con- trast, remanufactured products were completely disassembled and cleaned; parts were then re- placed or brought back to their original condition and reassembled from inventories of new and regauged parts. The original product thus lost its identity, and the final compressor was virtually as good as new. (See Exhibit 3 for a fuller descrip- tion of remanufacturing.) The primary competi- tion faced by Copeland wholesalers carrying its rebuilt or remanufactured compressors consisted of 200 independent rebuilders who competed on price. Copeland's primary selling point in this market was the reliability and quality of its products. Hermetic Compressors During the 1950s, Copeland moved into three segments of the growing air-conditioning market: commercial, residential central, and room (or win- dow) units. While semi-hermetic compressors could be used in larger commercial air-conditioning applications, they were too powerful and costly for smaller commercial and most residential use. For these new businesses, the company, as Diggs later put it, "blundered into hermetics," but brought with it a "semi-hermetic mentality: rugged, ov- erdesigned, customized, and low volume." Her- metic compressors were so named because they were totally sealed within a welded shell and thus were not field-serviceable. For this reason, her- metics were also called "welded" compressors, and Copeland referred to its own products in this category as Copelawelds. (See Exhibits 2 and 4.) From the 1950s on, Copeland faced much tougher competition in the three air-conditioning markets than in refrigeration. In each segment, it faced Tecumseh Products, a high-volume, low- cost producer that sold its bills of materials to customers and refused to customize its products; it also faced captive producers. Moreover, air- conditioning OEMs had thinner margins than their refrigeration counterparts and bought com- pressors on price. Wholesalers as well as OEMs. usually bought new compressors; at $80-$120 (contrasted with $500-$1,200 for semi-hermetics), field repairs were seldom cost-effective, and re- builds were neither essential nor widely available. Compressor Manufacturing From their inception, both Copelametics and Co- pelawelds were manufactured at the Sidney plant. The company purchased raw castings, which would become the bodies of its compressors, as well as most other components such as valve plates, pistons, and rods. Copeland's skilled machinists then milled, bored, and drilled the many openings, surfaces, and parts, first to rough dimensions, and then, on finish lines, reamed and honed to precise tolerances (.0001 inch). After machining, parts were brought by miles of overhead conveyors to the assemblers at carousels. These slowly ro- tating lines had 20-25 workstations, at which fixtures, sized for a particular model, held par- tially assembled compressors in place. Each as- sembler added a component or a subassembly that had been put together elsewhere. The compressor was then dried out in the dehydration department, final components were added, it was tested for leaks, painted to retard rust, packed and shipped. All the steps following the machining of compo- nents were loosely referred to as "assembly." Matt Diggs Arrives Matt Diggs's first contact with Copeland came in 1969 as a member of a Booz, Allen & Hamilton consulting team called in to investigate Copeland's cost and quality problems. The team recom- mended management changes and marketing re- organization, leading the board to hire a new president, Carl Moeller, a General Electric exec- utive who had run the company's air-conditioning business. Moeller concentrated on putting in tight financial controls and other complex systems; these changes sensitized managers to quality and impressed on them the need for more than words or slogans. In 1972, Moeller hired Diggs as vice president of marketing. Diggs shifted the company's marketing ap- EXHIBIT 4 Timeline COPELAMETICS: basic design & technology established wholesaler network developed COPELAWELDS: 1940 1950 Rebuilding rebuild plants licensed Wichita bought a/c markets entered i 1960 the welded problem" 1965 service teardown begun Brooklyn Avenue begun CR/Hartselle: CR design 1970 low cost emphasized 1972 1974 Rushville: planning team established site chosen ground broken product shipped approval to move out given - planning begun team established site chosen ground broken product shipped Sidney: (Copelametics and Copelawelds) - Skinner hired Granville hired planning begun . Ruwe hired . Gerzina appointed project manager Shelby: differentiation emphasized CR manufacturing process developed team established site chosen ground broken product shipped 1976 1978 1980 1982 proach to one of defining and serving distinct markets. Previously, he observed, We had customers and sold to them. But we did not differentiate between them as parts of different markets. We were customer-ori- ented-very flexible, very accommodating-but not market-oriented. Diggs also set up a Product Services group. within marketing to focus on after-market sales to re- frigeration wholesalers. Evolution of the CR Product The "Welded Problem" During the 1960s and early 1970s, the company invested major resources in its hermetic com- pressors. Yet their contribution remained small, their costs high, and their failure rates just mar- ginally acceptable. Management referred to these difficulties as the "welded problem." Moeller thought the high costs resulted from an absence of vertical integration and proposed that the company be- come more integrated. He also initiated work on a new hermetic design called the CR line, a product whose vertically integrated production would cut costs by 20% and which would be aimed at the heart of the unitary residential market. Diggs, however, viewed the situation differ- ently. He saw the 1973 energy crisis as a once-in- a-lifetime opportunity to differentiate Copeland's hermetic products, normally considered commod- ities, by their energy efficiency. Moreover, Diggs reasoned that Tecumseh, which was no more vertically integrated than Copeland, actually de- rived its cost advantage from skill in high-volume, repetitive manufacturing. He concluded that ver- tical integration was not the answer to Copeland's welded problem. Product and Process Design After Carl Moeller's retirement in 1975, Diggs assumed the presidency of Copeland. Immedi- ately, he pressed for a CR design that was highly energy efficient rather than inexpensive; indeed, his insistence on improved reliability ultimately led to cost increases. The number of parts was reduced, all major components were standardized across models, and the number of models became few and standardized. The design process for the CR differed from past design efforts in several ways. For example, Diggs wanted a quantum change in quality; to get it, he insisted on three stages of reliability testing: accelerated performance and life testing during development to predict field performance; field testing to verify that performance; and qual- ification testing to determine whether the com- was visually, dimensionally, and functionally within specifications. Improved reli- ability was also sought by bringing engineering and manufacturing together before, rather than after, designs were ready for tooling, initiating a practice that would be used in the future for all new products. pressor The design group began by considering such problems as how to reduce defects and scrap. Its constraint was an assumed total investment in the CR project of $10 million-$12 million. But when members of the group would propose a new idea, Diggs would say, "It's not good enough. Let's do it right," and would send it back for revision. Eventually, "right" would come to include $500,000 for an automated air gap station, which ensured that the rotor (which was pressed on one end of the crankshaft) was absolutely centered relative to the stator, as well as automated body and piston lines, which had solid-state programmable controllers and automatic tool adjustment. As one observer summarized the process: The vision came from Matt. If the team had been left to its own devices, the results would have been fairly pedestrian. Matt pushed and encouraged, and that's what led to the bold stroke. In its final form, the bold stroke was a $30 million investment in a new design and a new manufacturing process, to be located in a new plant, adding one million units of capacity to the industry. To make an investment of this size pay off, Copeland, whose net worth was then $50 million, would have to take at least 10 market share points. Location of Manufacturing Until mid-1976, it had been assumed that the CR would be made at Sidney, replacing existing Sid- ney Copelawelds. But a bitter three-month strike and customer concerns about potential disruption of supply changed Diggs's perspective. Moreover, the prevailing manufacturing mindset at Sidney also pointed toward a new location. An outside consulting firm was called in for advice; it con- cluded that Copeland would surely fail if it tried a new product, a new plant, a new process, and new management all at once. Nevertheless, Diggs decided to proceed with the new plant. To coordinate all aspects of the project, Diggs created a project management team reporting directly to him. Assistant Project Manager Mi- chael (Mike) O'Keeffe summarized the team's role by saying, "We forced people to communicate and to put their cards on the table." HARTSELLE. The team's mission was to find a site for the factory, supervise its construction, and begin the hiring process. After considering several southern sites, it settled on Hartselle, Alabama. To manage the factory, Diggs wanted someone who was progressive, ambitious, strongly oriented to quality, and who knew the compressor business. In April 1978, he hired Richard (Dick) Peltier, who had spent 10 years building hermetic com- pressors at General Electric, as plant manager. Peltier recalled: Matt said to me. "You need to be good at i precision machining and assembly; anything else- like trying to lower costs through vertical inte- gration is peripheral. Your mission is to make. a high-volume, narrow product line in long runs at low costs. There will be lots of drive on the part of this organization to proliferate the product; you resist, and I'll back you." Key Manufacturing Tasks To achieve high volume at low costs, Diggs be- lieved quality was essential. He had therefore steered the engineers toward machines and proc- esses that would consistently hold precise toler- ances, making assemblers' jobs simpler and final products more likely to work. For these reasons, planning and investment had focused on the machine shop. In the same spirit, Peltier chose process control in machining as his key task and developed systems to make it a reality. He con- centrated on statistical quality control because of its fit with the quality-through-automation ap- proach to equipment. To support this approach, the quality manager became the number-two man at Hartselle-"a very unusual situation," accord- ing to O'Keeffe. Manufacturing-Marketing Relationships Hartselle opened its doors in record time. The first products were made in October 1978. To get from start-up to full production, however, Diggs insisted on a more moderate pace. He told Peltier: "Tell me how rapidly you can come up and still keep things under control, and that's how many orders we'll take." This directive was quickly tested during Hartselle's second winter, when demand for the CR escalated rapidly. At that time, Diggs accepted orders only for what Hart- selle could machine, temporarily shifting addi- tional CR assembly to Sidney (because Hartselle I could machine more than it could assemble, this shift left the two activities in balance). But many customer requests still went unfilled; as Diggs recalled, "Some of our customers were furious." The effects of such a paced start-up were felt throughout the organization. According to O'Keeffe, "Marketing had always run the company, so they just couldn't believe it. The change was visible at the highest levels, and it went down hard." But manufacturing at Hartselle was still driven by the market, as Diggs noted in retrospect: We were working with a narrow conception of manufacturing strategy: What does it take to serve this market? It was really a marketing strategy, with manufacturing the key to achieving our marketing objectives. We knew that our prod- uct-design features could be matched in a few years, but we wanted to make our competitive advantage endure. We did that through the re- liability provided by our manufacturing process. Manufacturing's support of marketing was given i visibility by Hartselle's use as a showplace for customers. To convince customers that Hartselle's quality could not be beaten, plant tours were frequently arranged. Results and Learning Rewards for the paced start-up came almost im- mediately. High-volume production was attained without a hitch-something that had never before happened in the air-conditioning industry. Pre- viously, all new products had experienced call- backs, field failures, or other quality problems. Industry veterans were amazed; as one observer noted, "word spread like wildfire." The CR took a respectable share of the hermetic market in 1980 and held a quarter of the entire unitary market the following year. Subsequent to Hartselle, none of the captive producers expanded their hermetic production. Diggs summarized the impact that Hartselle had on Copeland: Our present management team began to come together around Hartselle. We learned we had to excel, not just be good. We found we could break some barriers on quality and on process. And we saw from our market results that we could differentiate a black metal device in the minds of our customers. The term "focused factory" was used for the first time at Copeland to refer to the Hartselle plant. After having seen the word "focus" in another company's annual report, Diggs described Hart- selle, in his own 1978 annual report, as a "focused plant, where the organization, manufacturing processes, and facilities are all concentrated on a single product-the CR compressor." Hartselle had begun as an opportunity to "step out" and create an enduring competitive advantage in a single product line; over time, its impact was far greater. According to Diggs: Before Hartselle, our plants made stuff. But after Hartselle, our orchestra had a new section in it, and we had a new weapon-a tank. For the first time, we realized that manufacturing could be a competitive weapon. Rebuilding and Remanufacturing Copeland's Early Rebuild Efforts, 1960-71 During the 1960s, Copeland licensed three inde- pendent firms to rebuild its semi-hermetic com- pressors, bought a fourth, and began rebuilding at Sidney. The latter activity, called "service teardown," was located in the midst of original manufacturing. Control was loose, and rema- chined parts often intermingled with new ones, becoming incorporated in new compressors. Sep- arate accounting procedures, materials systems, and qualification areas were therefore developed, and rebuilds were assigned to the new Product Services group, which brought together all after- market activities. Brooklyn Avenue, 1972-76 Service teardown was next moved to an old wooden structure on Brooklyn Avenue, about three miles from the main Sidney plant. Because of their proximity, the two plants were governed by the same union and same seniority rules on bumping. Diggs began to appreciate the need for a separate work force to perform rebuilding because of the specialized knowledge and skills required. Rebuild workers not only had to recognize, by sight, the enormous number of parts contained in current models, but also had to recognize compressor parts going back 20 or 30 years. In addition, they had to be able to spot defective parts, know how to test for defects, when to throw parts away, and how to salvage what could be rebuilt. While the move to Brooklyn Avenue had reduced rebuild problems and improved after- market delivery, problems of materials control, layout, and capacity remained. To Diggs, these issues were secondary to the potential threat posed to Copeland by the poor quality of its rebuilt compressors. He commented: Our failure rates were upsetting. But be- cause wholesalers provided rapid replacement, our refrigeration customers had not yet perceived a problem. Even so, I felt our rebuilds were making us vulnerable at the heart of our core business. By then, I perceived the quality problem as inherent in the rebuild process itself. I wanted new processes in a real factory and a dedicated. work force. Diggs devised a two-pronged attack: moving rebuilds out of Brooklyn Avenue and establishing clearly in the minds of customers the superiority of Copeland's rebuilt products. The term "reman- ufactured" would be used to herald the change and to distinguish the new products. In order to escape the work-force disruption caused by bump- ing between original manufacturing and rebuild- ing, Diggs concluded that semi-hermetic reman- ufacturing would have to be located outside of Sidney. The site chosen was Rushville, Indiana. Remanufacturing at Rushville The world-class remanufacturing plant envi- sioned by Diggs had several objectives. Like Hart- selle, it was expected to differentiate Copeland products through manufacturing excellence. The production process would therefore be state-of- the-art, especially when compared with rebuild- ing. The latter was typically a labor-intensive, cash-cow business in which equipment investment rarely exceeded $200,000. By contrast, Copeland expected to spend $6 million on plant and equip- ment at Rushville in order to "do it right." To begin, Diggs set up a project team headed by Bruce Oelschlager, who had run the rebuild plant bought by Copeland; its aim was "to rely on the process to control itself." The team designed a layout and materials handling system that ensured the product was never off the line. Flex- ibility became a primary goal, since Rushville had to handle all 10 semi-hermetic bodies. Dedicated fixtures, designed for one or two body sizes (as in original manufacturing), were therefore ruled out. At each disassembly step, broken or obsolete parts were thrown into scrap bins and segregated by metal type, as were all running parts, such as rod-and-piston assemblies, which were routinely replaced. Rotors, stators, and bodies were rema- chined and requalified in separate routings that fed back to the assembly area. Other salvageable parts were remachined and regauged, with each station in the machine shop reworking a partic- ular part to precise tolerances. Fine-tuning was the heart of the operation, in contrast to the more substantial work, using large machine tools, that typified original compressor manufacturing. After machining and gauging, requalified parts re- turned to the assembly area, where they were put together in sequence, reversing the steps that had been used to take them apart. Quality was sought through investment in one-of-a-kind equipment (such as the derust washer designed to clean all body cavities and all iron and steel parts); through special gauges that were themselves requalified every six months (a desk full of small gauges for measuring crankshafts to 0001 inch cost $50,000); and through efforts to ensure operator responsibility. Operators were trained to both perform and inspect work activi- ties, including their own setups; they were also held responsible for the quality of parts that left their areas. Once Rushville was up and running in 1980, reporting relationships were reorganized. Reman- ufacturing was pulled from Product Services to become part of operations, even though other after-market functions stayed in marketing. The shift in technology was the major reason for regrouping. Now that remanufacturing relied upon sophisticated production and quality-control methods, manufacturing expertise was deemed essential for proper control.. Large Cope Focused Factory: Shelby Stimulus for Change Once Hartselle was operational and Rushville. planning was underway, Diggs turned to the remaining products at Sidney. In particular, he was concerned about large Copelametics, the 20- 40 horsepower models that were the heart of the refrigeration market. These could be distin- guished from other Copelametics by their manu- facturing requirements and by their markets. Tooling, fixtures, and body lines, for example, were all heavier and more costly than for smaller models. Several factors triggered the decision to move "large Copes" out of Sidney. Two were technical. Copeland had recently devised a new type of valve that was 15% more energy efficient and thus particularly cost-effective for large compressors. Use of this valve, however, would put more stress on other components. For this reason, and because large Copes already had higher failure rates than desired, Diggs saw the new valve as an opportu- nity to upgrade the entire product design. Second, the high failure rates of large rebuilt compressors were due not only to the rebuild process used prior to Rushville, but also to marginal tolerances established during the products' original manu- facture. Therefore, retooling the machine shop for large Copes would enhance Rushville's long-term success while also improving the reliability of new products. But making these product and process investments in Sidney seemed unwise to Diggs, particularly after a 1979 strike rekindled the question of continuity of supply. After pickets blocked the company's directors from entering the building for a board meeting, Diggs recommended and received approval to move large Copelametics out of Sidney. He observed, "We had a very high market share and customers who were very de- pendent on us. I could no longer take the risk of being held hostage by the labor situation." Large Cope Focused Factory (LCFF) Project Diggs asked product engineering to upgrade the large Cope designs to improve their performance and reliability, and advanced manufacturing en- gineering to size the plant, plan the investment, develop a layout, and order equipment. But when offered several early investment proposals, he rejected them, because of their high costs. O'Keeffe, who by then was Diggs's assistant, recalled, "The engineers were frustrated because they could not make it perfect." Once a more realistic budget of $20 million was established, Diggs withdrew from active project management. The project team re- ported to the vice president of manufacturing. whose greatest strengths lay in technical problem solving. SELECTIVE INVESTMENT. With limits now estab- lished on Shelby spending, the engineers quickly became more selective about investment, looking for ways, as one member put it, "to get the biggest bang for the buck." Assembly was given top billing because the cost of completely new assembly equipment, which was desirable because of the complexity of Copelametics, was only $3 million. Engineers then developed a method for investing selectively in the machine shop. Because ease of assembly required certain tolerances to be achieved consistently, manufacturing engineers asked product engineers, What are the dimensions crit- ical to Copelametic performance? These were then color-coded by degree of importance. Next, quality control was asked, What tolerances can you hold? These responses were also ranked and color-coded. When the two sets of color-coded drawings were placed side-by-side, major deficiencies were im- mediately visible, indicating areas of needed in- vestment. This procedure led to a $6 million body line, which had precision boring, drilling, and honing machines that created absolute perpen- dicularity between cylinder bores and crank- shafts, and a $5 million crankshaft line with programmable controllers. NEW ASSEMBLY. That Shelby emphasized assem- bly to a greater degree than Hartselle reflected a basic difference between semi-hermetic and her- metic compressors. Because of their design, the former had many more parts per unit; because of product proliferation they also had many more parts overall. According to one expert: Copeland's semi-hermetic compressors were designed in the 1940s and 1950s, so they are much more likely to fail if they are not put together right. There's also a wider distribution of dimen- sions, so you get more variability among parts. For example, if you've got a "big" cylinder, you're going to need a "big" piston-even though we're i talking tenths of thousandths of an inch, it makes a difference in ensuring that parts fit together and function. Assemblers of semi-hermetics will therefore do a lot more sorting of parts and more fitting and fussing. Semi-hermetic assembly was therefore heavily operator-dependent. By contrast, welded products like the CR were easier to put together; if their parts were precisely machined, they were also. guaranteed to function properly. The implication, according to Peltier, was that: At Hartselle, we needed to control the proc- ess, so we paid a lot of attention to the machine shop. But at Shelby we needed to control the product, so assembly was critical. Where Cope- lametics are concerned, operators must look at every product they're working on to ensure that they have the right parts, that they're putting them together correctly, and that the right prod- uct is shipped. For these reasons, an intelligent, well-educated work force was a prime factor in site selection. Shelby had a good school system, and half of the hourly workers had some college education. Vir- tually all were trained for several operations. Innovations in individual workstation design were also made to ensure that compressors were as- sembled correctly. What to Do About Sidney By mid-1980, Copeland had focused factories op- erating at Hartselle and Rushville, and was plan- ning a third at Shelby. Sidney's collection of diverse product lines had been greatly reduced. But even after large Copes were moved out, the factory would still be home to eight Copelametic and five Copelaweld families. Diggs described the situation: We had initiated three bold strokes and now were left with a mediocre plant. There was no marketing imperative, no external force driv ing change, no complaints about quality. But I could see that Sidney's products were not going to be adequate in the future; there would be cost. and quality problems somewhere down the road. So what should be done with this plant? Closing Sidney was an option that manage- ment preferred not to take. Copeland had been headquartered there for many years, and Diggs felt responsible for the work force and the local. community. Moreover, if products were moved to another site, all Copelametic blueprints would have to be redrawn, since manufacturing methods had evolved at Sidney through years of shop practice. Copelametic manufacturing was now run by "managing the gaps" between blueprints and actual products; these gaps were spanned by years of experience carried in operators' heads. It would take enormous work to redraw the blueprints and develop test programs for each one, a necessity if the factory were moved. Because of the time and cost involved, and because of the age of Sidney's products, a move could not be justified. In September 1980, Copeland hired a new plant manager, Wesley (Wes) Granville. Diggs recalled his expectations: I wanted someone who could manage people. I hoped we could get the labor situation stabilized and could run the plant better, but I didn't think the labor problem was solvable. We still had no idea of restructuring Sidney; we just wanted to do it better. Granville was experienced in machining and in statistical quality control. He considered his prime task to be the development of people who could run their own plant, and he quickly got to know his hourly workers on a first-name basis, Granville recalled: We had to get the corporate guys out of Sidney. At the time, you'd walk into the plant and they were everywhere. The plant people were dependent on them. That kind of dependence can only be changed by growing people so that they not only learn their own roles, but also how to work as a unit. Early Discussions About Change A few weeks after he was hired, Granville began talking with other Sidney managers about changes in the machine shop that could be made without major capital investments. A prime goal was the reduction of Copelaweld costs. Diggs called in Wickham (Wick) Skinner, who had developed the focused factory concept, to consult with them about how to modernize Sidney's "white elephant." In January 1981, he hired Dean Ruwe as vice president of operations. Ruwe spent his first few months on the job trying to understand Sidney better. The process was immensely frustrating, as he later acknowl- edged: Nothing I had ever encountered had the complexity and problems I found at Sidney. At first I thought maybe we could try harder, but then I saw that they had been trying harder for a long time and just couldn't get it any better. More basic change was needed. Throughout 1981, Ruwe orchestrated an educa tional process based on Skinner's work on man- ufacturing strategy. Diggs later acknowledged that he had been frustrated at the time by the slowness of the process, but felt that "we needed the kind of consensus that Dean built. He had to create a manufacturing management team that functioned in a different way." O'Keefe also cited Ruwe's contribution: We had floundered for months talking about Sidney and really didn't make any progress until Dean had been here for awhile. He understood what Matt was asking for, saw Wick as a resource, and knew how to involve people. The year-long dialogue produced four stra- tegic goals for Sidney: a quantum improvement in Copelametic quality, a quantum improvement in Copelaweld costs, a quantum improvement in systems, and simplification of certain design spec- ifications. These goals were refined, and in some cases, quantified. The idea that Sidney had to be focused through the use of "plants within a plant" began to take hold, although there was some resistance at first. Several managers felt that if Sidney were split in this way, costs could only go up because two of everything-for example, man- agement teams, engineering groups, and mate- rials systems-would be required. Ruwe, however, with support from Diggs and Skinner, proceeded "on faith." Eventually, the experience of wrestling with these problems brought home the real mean- ing of focused factories, as Granville recalled: When most plants are built, they're expected. to concentrate on a particular product. That's not peculiar to focused factories. But when you get an old plant like Sidney and try to split it up, then you really begin to understand what's in- volved in focus. For us, that's when the concept finally sunk in. Over time, many terms were applied to the project; the one that stuck was "Sidney Revitalization." Sidney Revitalization In early 1982, Ruwe replaced Sidney's large plan- ning group with a much smaller one consisting of Granville, O'Keeffe, who was now manager of corporate advanced manufacturing engineering, Bud Gerzina, who had managed a number of Copeland's smaller manufacturing improvement projects, and himself. The group had two options for separating the plant: a process split, as at Rushville; or a product split, as at Hartselle and Shelby. In either case, Sidney's existing layout and union agreements would serve as points of departure. Existing Layout All machining was done in one half of the plant; the other half, consisting of large, enclosed, air- conditioned rooms, was devoted to assembly. (See Exhibit 5.) Both areas were organized by depart- ments, and each department contained function- ally similar lines. In machining, for example, all Copelametic and Copelaweld body lines were grouped together; each, however, had separate departments and foremen because of the many people and machines involved. The Copelaweld and Copelametic piston departments were simi- larly organized, although a single foreman over- saw both. Assembly followed much the same pattern. Copelametic carousels were interspersed with Copelaweld carousels and together formed a single department with two foremen. Both product lines went through the same dehydration, paint- ing and finishing, and inspection and packing departments. A single foreman oversaw each of these departments. Work-Force Seniority Rules While most equipment was dedicated to particular product lines, workers were not. In machining. for example, layoffs or transfers were made solely by component line. Each worker could bump into any other line within his or her job classification; thus, a drill press operator could work on any line requiring that job classification, whether it in- volved Copelametics or Copelawelds. As a last resort, bumping was even permitted between ma- chining and assembly. Under this system, the greater seasonality of welded products caused considerable movement. Management therefore wanted to increase work-force continuity, whether a product or process focus was chosen, and viewed modification of the union contract-for example, the creation of separate work forces governed by their own bumping rules-as a top priority. Be- cause labor relations had improved considerably since Granville's arrival, management was opti- mistic that it would gain labor-force cooperation in making the necessary contract changes. Process Focus: Machining versus Assembly Under this option, Sidney would be split to reflect the differing technological, cultural, and skill requirements of machining and assembly. Most investment, for example, was concentrated in machining. Many managers considered Cope- land's core competence to be its ability to machine cast iron and steel to precise tolerances. And in this area, the focus was on equipment. Even though machining foremen had to manage people and materials as well as equipment, when asked to cite their biggest problems, they almost always talked about machines. Because process control, setup times, equipment maintenance, and down- time were such key concerns, the machine shop also required the bulk of Sidney's engineering and maintenance support. Assembly, by contrast, employed less sensi- tive equipment; as Granville noted, "If the parts are there, you make standard." When asked about their biggest problems, assembly foremen usually EXHIBIT 5 Sidney Plant Layout in 1981: Process C/Ma Plate Machin Small Cope Body Mach Plant Services C/M Head Mach'y impactor Crank Machining Bar Stuck Storage CM & CW Casting Storage C/W Piston C/W Valve Plate Mach's C/W Head Machining GA Parts Mach's C/Mon Machining Mach BSS Smal Parts CM Cra Mach's Heat Theat C/W Body Mach's Corp My Engrs CM Body Stock Large Cope Body Mas BR Body Machining E Large Cope Body trough) C/W Body p Purchasing & Plant Offices CW&CM Motor Stock Cate CM Parts Hanging CM Body Hanging C/W Sub Assy C/W Assembly CM Assembly .CM Assembly OC Note Bulding A- is actually located directly south of main building CW&CM Purchased Parts Receiving CW Subs C/W Parts Hanging cw. Mach'd Body Stock C/W Assembly Corporate eng Labs C/W Fil Processing OM F Processing Receiving Boler Docks Room C/W Shel Bracing Washing C/W Mach'd & Purchased Purchased OM Machid & Parts Parts Stock Stack CM Body Sorting C/W G Farts CW Single Pack Mach CWT C/W Finished Compressor Storage CM Compressor Stage CW Mun Mach C/W Shell Welding CM TOM MANY Charts -Process Rew Shell Shock CW CM Pack C/W CM Shipping SMI Receiving Shel Stock talked about people. John Vordemark, assembly manager, commented on his priorities: In assembly, you want to concentrate on max- imum efficiency of people-that's where you spend your time. And then you guard quality. In ma- chining, it's the other way around: you do every- thing to get a good part. You never jeopardize that for efficiency or cost. These differences resulted in distinct machining and assembly cultures. Granville described the differences: In machining you get dirty. Your days have more variety, you set up your machines, there are breakdowns, you move around more, there's greater freedom. In assembly, you're putting the same type of components together over and over. Breakdowns are rare. It's cleaner, quieter, and you take breaks with a whole group of people. It's almost like a family. These cultural differences extended into the com- ponent lines and were reinforced by the process of job bidding, which allowed people to gravitate toward the line cultures of their choice. Emerging global competition also made the process focus option more attractive. International markets were rapidly becoming more important, and Copeland already had several overseas plants. Early thinking about a global strategy suggested that not all plants should be involved in both. machining and assembly. The two processes were likely to be decoupled, with machining of partic- ular components or bodies concentrated in differ- ent plants and assembly assigned to plants closer to markets. To inaugurate this global manufac- turing organization, several managers argued, why not start with Sidney? WHAT WOULD BE REQUIRED. While machining and assembly could be split without moving any equipment, a first-rate layout would require more substantial moves. Interwoven product lines would have to be separated so that within the machining plant, Copelametics and Copelawelds had their own separate areas. A more rational production flow would also require changes in layout; at the moment, after rough machining on several body lines, compressor bodies were placed on skids and moved to another set of rough machining oper- ations, then stacked and moved to the finish. machining lines. Rearranging these lines would achieve significant improvements in throughput, materials flow, inventory, and labor utilization, while also bringing operators performing related tasks within shouting distance of one another. These changes would not, however, require relocation of Sidney's "monuments." The monu- ments were large pieces of equipment whose foundations were linked to the building's infra- structure; for this reason, some managers feared that they would crumble if moved. Among the monuments were a five-stage washer, a heat- treating furnace, and the dehydration line. But the monument arousing greatest concern was a 17-station transfer line that machined bodies for small Copelametics and accounted for 100,000 units per year. Not only were its foundations sunk into the floor, but it had also taken 18 years to fine-tune the machine's alignment so that it con- sistently held tolerances for the critical center line of small compressors. The transfer line would not be moved if Sidney were focused by process; a product/market focus, on the other hand, might require the line to be relocated. Although splitting Sidney by machining and assembly would not require major work-force reassignments, they were nevertheless viewed as desirable. To pursue this route-changing bump- ing rules, for example, to reduce the volatility of the work force-management would have to ob- tain modification of the union contract. Product Focus: Copelametic versus Copelaweld Under this option, Sidney would be split to reflect the product and market differences of Copela- metics and Copelawelds. Semi-hermetic growth, for example, was predicted to be very small. Copeland aimed to hold onto these markets through superior quality, reliability, delivery, and replace- ment, while continuing to proliferate its products. Almost half of all Copelametic orders were for five or fewer units; 80% were for ten units or less. The maturity of the basic product design, the flat, stable market, and the already large investments in Rushville and Shelby suggested that future investments in Copelametics would be incremen- tal, aimed at preserving and extending Copeland's leadership position. Copelawelds, by contrast, were sold to cus- tomers whose requirements often changed quickly and dramatically. These sales fluctuations im- posed special delivery demands. Peltier observed: In commercial refrigeration, you need reli- able delivery. The customer says, "I want three." You tell him when you can deliver; then he sets up his production. But you had better have them there on time because he has set his runs to conform to what you promised. In residential air conditioning, you need clockwork delivery. The customer orders 2,000 units and needs them by a certain date; you have to get the orders there on the day he wants them. The welded compressors faced intensified com- petition from new Japanese rotary technology and from Tecumseh; in contrast to the CR, whose market share continued to climb, the share of some Sidney Copelawelds had already begun to fall. For these reasons, welded products would demand a continuing infusion of engineering re- sources, new products, new technology, and up- graded facilities if they were to remain competitive and secure a position of cost leadership. WHAT WOULD BE REQUIRED. To split Sidney by Copelawelds and Copelametics would require a reorganization of the plant, since the two product lines were now scattered throughout the factory. (See Exhibit 6.) Both the amount of equipment to be moved and the scope of the moves would be significantly greater under this option than under a process split. For example, equipment would have to be regrouped so that Copelametic ma- chining was next to Copelametic assembly; the entire Copelamatic plant would then have to be. separated from the Copelaweld plant by a brick wall. Other physical changes would be needed to reinforce these efforts, ensuring that workers. identified with products and their customers rather than with crankshafts and pistons, or machining and assembly, as in the current culture. Likely changes included separate parking lots, en- trances, and cafeterias for Copelametic and Copelaweld employees. As a critical step, labor policies would need to be changed to prevent employees associated with one product line from bumping or transferring into the other. Despite these complications, separating Copelametics from Copelawelds had strong intu- itive appeal. It acknowledged long-standing dif- ferences in the manufacturing demands imposed by the two products. Copelametic production, for example, was fairly stable over the year, its turnover was lower and workers more senior. And because Copelametic machinists used general- purpose equipment that performed but a single operation at a time, the pace was slower, with 100 rather than 1,000 pieces being turned out per shift. Quality was operator-dependent. Copela- weld machining, by contrast, involved higher vol- ume, higher speed, and dial index dedicated equip- ment that performed several operations at each station. Machines were more complex to set up and maintain, but required little of operators while they were being run. The result, as Granville noted, was that different kinds of people had gravitated to the two products: In Copelametics, you have older people, the graybeards, the artists who massage the equip- ment, while in Copelawelds, you have the young bucks, people who are resilient, who can deal with layoffs and recalls and the faster pace, and who enjoy riding the ragged edge. The two also had different scheduling prob- lems in assembly. The greater part of Copelametic scheduling could be done by model and horsepower (the "mechanicals"), while extensive proliferation came in the final stages: "electricals," valves, labels, and such. Copelaweld scheduling, on the other hand, had to take account of proliferation from the beginning, creating two schedules-one for the compressor and the second for its shell- so that compressor and shell would meet at the right point. On February 8, 1982, O'Keeffe, Gerzina, Granville, and Ruwe met for a final time to decide how Sidney should be focused. They knew that a decision had to be made. the end of the meeting. and recommendations prepared for Diggs, so that attention could shift to problems of implementa- tion. EXHIBIT 6 Sidney Plant Layout in 1981: Product Copelaweld Copelametic + Administrative Note: Building A- is actually located directly south of main building