Question: How do the changes Harrah's is making fit with relevant theory on motivation and more broadly? Goals; Connections to Theoretical and Empirical Research. Makes appropriate,

How do the changes Harrah's is making fit with relevant theory on motivation and more broadly?

Goals;

Connections to Theoretical and Empirical Research. Makes appropriate, insightful, and powerful connections between the issues and problems in the case and relevant theory and empirical data; effectively integrates multiple sources of knowledge with case information.

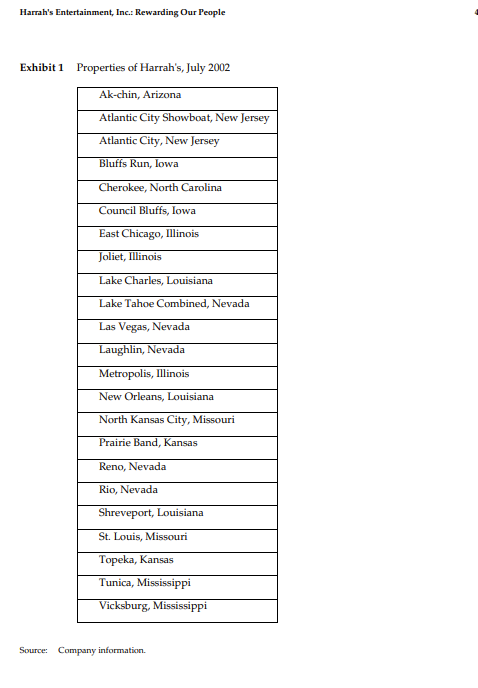

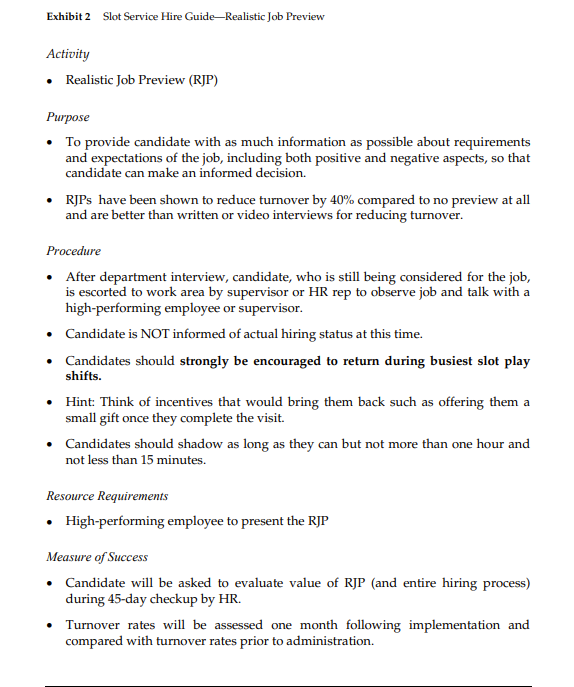

Harrah's Entertainment, Inc.: Rewarding Our People How do you change the working premise for our people from being controlled by their limitations to realizing their possibilities? -Gary Loveman, Chief Operating Officer, Harrah's Corp. Marilyn Winn ordered a cappuccino and sat down at a quiet corner table in the French Roastery Caf at the Rio Casino. She had a half hour to collect her thoughts before meeting with Gary Loveman, the president and chief operating officer (COO) of Harrah's Corporation. As the head of human resources, Winn had been a central force behind getting employees excited about Loveman's customer service goals. She had helped implement his incentive pay plan to reward employees for improvements in customer service metrics at each of the Harrah's properties. The incentive pay plan was supposed to instill a competitive spirit in the employees, both in competing against rival casinos as well as competing with their own record of past performance. The secondary motivation for the incentive plan was to tell employees that they were at the heart of Harrah's strategy, that even though the company prided itself on being customer obsessed, it also respected and rewarded its employees. The trouble was, in the previous quarter ending August 2001, customer service metrics had increased positively but not to levels that merited a payout at most properties. Because the program was a continuous improvement program, the low-hanging fruit had by now been picked. Raising service improvement levels was becoming harder and harder work. Winn knew that some employees tire of working hard and coming close to reward levels and then not getting rewarded. At what stage would employees say, "Forget it"? How could they keep the incentive plan fresh? Loveman had asked Winn to meet with him on this topic, and he expected her to give him a full evaluation and recommendation of how to motivate employees either with this incentive plan or through newly designed programs. The incentive plan had cost $16 million in the previous year, and that felt like an especially big number now that revenues were dropping off because of broader economic conditions. Were these customer service payouts the most efficient way to make Harrah's a service-driven and customer-driven company? Winn had an operating background. She understood what making budget meant. She also knew that Loveman was tough minded and numbers driven. As she played with the Equal packets on the caf table, Winn felt she was in a perplexing situation. Harrah's in 1997 began to shape a new operating strategy that distinguished it both from its own past and from its competitors. Most casinos that competed with Harrah's in Las Vegas built "mustsee" new properties to outdo their rivals in order to attract new customers. 1 But the new properties usually performed best in their first or second year of operation and then plateaued, and Harrah's decided this was not an efficient method of sustaining revenue and earnings growth or return on investment. Harrah's moved from being a product-based company like most of its competitors to being a marketing-based company. Newly hired marketing executives brought expertise in database marketing from academia and from other industries such as financial services and airlines. They created the Total Rewards program at Harrah's to gather information and understand customer preferences so they could tailor the most appropriate marketing strategies and monitor and improve customer loyalty. The hope was to reap a larger share of customers' gaming budgets for existing properties and focus on increasing same-store revenues. Harrah's wanted customers to feel as if Harrah's was home base, a home away from home. Phil Satre, chairman and CEO of Harrah's for 12 years, said: We were heavily criticized at the time. Our competitors said we would perish without new attractions. Our employees felt they had nothing to brag about unless we were building the next new big thing. Meanwhile, with our new marketing database, we had built an F-16, but we didn't have a pilot. No one in operations was paying attention to the new marketing strategy. I consulted with Sergio Zyman of Coca-Cola, and he gave me some really good advice: if you want to build a marketing company, then empower the marketing people by making them operationally responsible. In 1999, I hired Loveman as chief operating officer and chief marketing officer because combining the roles made everyone else in the organization accountable to him for following through on the new marketing strategy. Loveman, who had been a professor at the Harvard Business School in service management, was very familiar with Harrah's business because he had been conducting on-site executive education courses for Harrah's for the previous few years. He knew Satre and the trouble Satre was having getting the plane off the ground. Loveman knew that a marketing-focused, customer-obsessed company was the desired outcome of his new operating role. But from his years researching, teaching, and studying organizations, he knew, "We won't get the marketing piece right if we ignore our people." History of Harrah's Culture Satre had started working in the 1970 s as outside counsel to Harrah's, when Bill Harrah was still at the helm of the company. Satre remembered how other Harrah's managers exhibited pride and ownership and considered themselves to be working for "the best in the business." Harrah was very particular about the condition of the properties, and employees told one another stories about his forbidding any sign to ever be put up using scotch tape. An oft-told story involved his noticing that a light bulb had burned out in the casino and had not been changed and a casino employee saying defensively, "Sir, the bulb is still warm." The reputation that Harrah had at the time as a good employer helped the company in recruiting executives and retaining staff. It also helped Harrah in negotiations with regulators and local and state-elected public officials. But Satre said by the mid-1980s, "The company was suffering from too much of a good thing." The emphasis on employee loyalty had led to employees with high longevity and a pride in looking backward to tradition and how things had always been done. When Satre took over as president in 1984, this employee loyalty pulled the company back from progressing away from old entertainment formats, away from Las Vegas-based growth, away from any of the personal philosophies of Harrah. "Loyalty had evolved into entitlement. The answer to everything was 'that isn't the way Bill Harrah did it," '"atre said. This was very frustrating to the CEO, who felt as if he had a deep understanding of Harrah himself. "Bill would not have put this company in a mayonnaise jar and put it out on Funk and Wagnall's porch and said "this is how it is.'" There was resistance from upper management as well as the ranks, especially to greater centralization or oversight. "My casino is my casino" was the attitude of many managers at various properties around the country. They did not want to share information across properties, agree to a companywide increased emphasis on slot machines over table games, or implement new strategic internal policies. Satre said, "What we had in 1998 was a culture that was not competitive. The measurement was 'How is morale?' and 'Let's not upset these employees that have been here 15 years.' I needed to make employees see the connection between what they did every day and how the company was doing." He wanted to replace institutional priorities of long tenure and employee happiness with ideals of excellence and customer satisfaction. "In the late ' 80 s, we had had a service edge over other casinos, but in the 90 s we had lost it. We were indistinguishable from our competitors from a service standpoint. And whenever we lost market share, the excuse would be, 'Well, that other casino has a fancy new restaurant." When Satre looked at the senior management he had inherited, he felt "they represented management rather than leadership. They had led by the rule book, and the rule book had been thick." The head of human resources had been inherited from Holiday Inn, which had bought and then sold Harrah's within a decade. "He was very hands off, and he didn't understand gaming or even hotel operations; his background was in hospital management. He was good at designing toptier senior executive packages, and he would run team management exercises at corporate, but he had little interest in addressing what the field needed." When Satre moved the headquarters from Memphis to Las Vegas in 1999 , the old head of HR was not interested in heading west. Satre was ready for a different kind of HR leader, someone who understood operations and business strategy and was willing to get his or her hands dirty spending time at the casino sites. A New Force in Developing People Winn was running Harrah's operations in Shreveport, Louisiana when the call came in March 1999. 'My secretary was speechless. She came running to me and said, 'Phil called.' You don't get called by the CEO every day. I said to her, 'We're on target for our quarter-why is Phil calling?'" When Winn was offered the job as head of HR for the company, it took some time to make a decision. She loved being in operations, and many operations people were skeptical of working at corporate headquarters and of the HR function in particular. Winn had worked in human resources from 1988 to 1995 then worked very hard to make the transition into operations. She ran slot operations from 1995 to 1997 in Las Vegas, with 220 people reporting to her, and then transferred out to Harrah's site in Shreveport as general manager, overseeing 1,400 employees. She said: "Operations is incredibly front line, especially slots, which was the bulk of revenue at the Shreveport site. In slots, we say the only reason for restaurants on the property is because slot customers get hungry. The only reason to have beds on the property is because slot customers get tired. As a group of employees, we were competitive and driven and I thrived on that. My head and my heart were really in the game at the properties." It was clear in Shreveport what her contribution to the company was; every quarter she was measured by her property's profit and loss. Headquarters would be different: much less transparency, undoubtedly more politics, and a different culture. Headquarters people often did not entirely relate to or value field experience, and operations people did not want intrusion by headquarters people. But Satre's excitement about the offer was contagious, and Winn felt this could be an opportunity to change the conventional standoffishness between field and headquarters. Winn's daughter also was eager to move back to Las Vegas because it felt like home, and her husband was amenable to the transfer. Winn accepted. Satre surprised Winn by asking her to present a human capital plan to the board of Harrah's within 30 days. In June 1999 , Winn presented her plan for re-creating the human resources function in a very different image. There would be a tripod structure: first, compensation and benefits; second, property products and services, which would include training and assessment; and third, executive search and leadership development. Some managers wanted Winn to focus primarily on executive compensation, as her predecessor had. But Loveman, the newly appointed COO, would not let Winn forget her responsibilities in the field for a second: "What about turnover, our turnover is sky high. I can't deliver great customer service unless I have a stable workforce. You need to get our people to stay with us." Lowering Turnover Winn started focusing on the tenure of Harrah's people. In properties like St. Louis, North Kansas City, and Tunica, Mississippi, turnover rates were estimated to be higher than 70%, but there was no quality reporting on turnover, no information on average tenure, and no analytical breakouts of how different areas were affected. The primary reason for involuntary terminations was attendance at work, which was the case with most retail businesses. "But unlike most retail businesses," Winn said, "I'm asking people to work weekends, holidays, and all-nighters." Winn and Loveman set a goal of 15% improvement, meaning that at the start of 1999, Wynn set out to bring down the previous year's average turnover of 45% to under 38.5%. Winn was able to achieve her goal, with an average turnover a year later of 34%. Focusing on turnover broke down into three categories: first, finding people appropriate for the job; second, the socialization process around bringing new employees into the company; and third, the long-term maintenance of employee motivation and performance. The Right People Loveman pushed Winn to be exacting about hiring standards. He said, "I want all managers to ask themselves, 'Is this the best person we can get for this job?' rather than, 'Can this person meet the minimum requirements for this job?' I want every employee at Harrah's to think about potential." He wanted to rely on standardized tests to set an impartial measure across the board. The individual interview would still be important during the hiring process, but Loveman wanted to move away from hiring " n from the gut. " Two tests, a short 20-question test for entry-level workers and a longer one for entry-level supervisors, had been created by Harrah's. For higher-level hiring, Harrah's purchased standardized testing instruments, including Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal, Gordon Personal Profile Inventory, Hogan Personality Inventory, and a leadership opinion questionnaire. Harrah's employed a director of assessments with a doctorate in psychometrics to interpret and evaluate the results. Harrah's Entertainment, Inc.: Rewarding Our People 403-003 Loveman believed hiring standards at the manager level should value world-class functional expertise over industry knowledge. Satre, however, had some reservations about these hiring standards, especially the trade-off between hiring MBAs from other fields at senior levels instead of promoting internally: We want more professional managers certainly, but at the same time, you have to have a visceral understanding of who the people are in this business, relate to the management and employees at all levels, and be good with the customers. You have to understand who our customers are, why they come here, why they enjoy this. Marilyn gets it, and she proved that in Shreveport, where she motivated her people to be very competitive and made winning market share a tradition, an expectation. She's a perfect example of a situation where promoting internally was the right thing to do and completely meritocratic rather than worrying about credentials on paper. Hiring and Socializing Process Winn's key initiative in creating a more formal socialization process focused on pre-90-day turnover, what she called "quick quits." "In the first 30 days, my goal is to velcro new employees to the wall, so they can't think about leaving, " Winn stated emphatically. "No one quits until we make sure there's nothing we can do better to keep them. If they're unhappy, we try to save them, move them to another role. The key to reducing turnover is finding the right folks and the roles can evolve. We try to find people who have an innate desire to achieve and learn and grow." All new employees would now follow a set sequence of interactions with Harrah's from their initial contact with the company through their first three months on the job including: 1. The Better People Inventory test, an instrument Harrah's had been using since 1992 to evaluate an applicant's service skills, teamwork, and dependability 2. An HR interview structured appropriately for their function and level 3. An interview with their manager, ideally the same day as their HR interview, or otherwise in the same week. All managers would have completed a required course on "hiring and retaining top talent." 4. A realistic job preview, with Winn instructing managers to "give them the good and bad" (see Exhibit 2 for an example) 5. After 30 days, a meeting with HR in which they tell HR how the job is going 6. After 45 days, an expectations meeting where a manager from the employee's department arranges a conversation to ask "Is this what you thought it would be?" (see Exhibit 3). Tom Jenkins was general manager of Harrah's Las Vegas, where turnover was at 16% compared with an industry average estimated by Casino Journal to be 22% to 23%. Jenkins had started as a fry cook in 1975 and worked his way up in the business. He had picked up management lessons over the years from emulating his best bosses. He had recently adopted the practice of a military leader, Admiral Abrascroff, who had been noted for turning around bad ships in the navy. Jenkins had heard that Abrascroff met with all new recruits to ask them what their aspirations were for their career and for their personal development and how he could help them. Jenkins made sure his managers realized how critical communication with new employees could be to lowering turnover. All the managers appreciated that Loveman had made it clear that the company was willing to invest in new employees. Most gaming companies did not invest much in new employees because they believed that their investment could not be safeguarded; too many employees left to work for competitors. Loveman tried to give them reasons to stay. He authorized special training in customer service, two days on-site with 20 people in each class. The company paid employees for attending the training by grossing their pay to the level of wages and tips, which communicated a high level of commitment to the employees from the corporation. New Reward System to Motivate Employees to Achieve Customer Service The concept of giving collective, team-focused bonuses or incentives was a novel idea in the gaming industry. Loveman said, "We introduced gain sharing to further our goal of customer service. We are a highly regulated business, where employees can lose their jobs for not interacting with customers in the regulated manner." For example, anytime an employee shook a customer's hand, he had to immediately turn both palms up to the ceiling and roll back his shirtsleeves to make sure the cameras in the ceiling could see him and could record that no cash had changed hands, that he had not taken a bribe. These strict regulations meant employees always chose less contact with customers, not more. Loveman explained: To the employee, bad customer service and little contact was better than too much customer interaction and losing your job. Providing service in gaming is also hard because customers are often losing. But good customer service can make customers feel like even if they don't win, they got an experience they were willing to pay for, they had a good time. That's what we want our customers to experience. Loveman also introduced a gain-sharing program, where employees were rewarded for improving customer service. There was no absolute level to reach, but employees were rewarded for percentages of improvement in customer service scores within the department and within the property, collected through the Targeted Player Satisfaction Survey (TPSS). Here is how the performance payout measures worked for the majority of Harrah's properties: The handout that employees received explaining gain sharing also stated, "Payouts for reaching customer satisfaction goals stand alone. Operating income results do not affect customer satisfaction goals." Loveman reiterated verbally to his employees at the inauguration of the program in 1999, "If you improve service, irrespective of financial performance, you will still get rewarded." By mid-2001, Harrah's had paid out more than $16 million in bonuses to nonmanagement employees through the gain-sharing program. In surveys each month, customers rated various aspects of service, using a letter-grading system of A through F. If a department could convert 4% of non-As to As, it would qualify for a bonus. Winn said, "Before we were not competitive enough, now we are getting everyone to think about service and about market share." For managers, bonuses used to be dependent only on improvements in operating income. Now, management bonuses were determined by multiple components: 25% based on market share, 25% based on customer satisfaction, and 50% based on operating income. Winn said: Harrah's Eintertainment, Inc.: Rewarding Our People 403-008 Managers tell me that they recognize they are evaluated differently in other ways, too. They would say, "I get heat if I have too much turnover. I make my employees take training seriously. I have to create an action plan if I get negative feedback from my direct reports. I have to make sure I hire using assessment tests even if I hate the tests." Most managers dislike the assessment tests because they want to promote people as a reward for doing well at their job. The problem is that a great cashier might not have the other supervisory skills necessary to be promoted, and the tests catch that. Views differed as to whether the incentive pay plan was an effective motivator. Incentive pay helped Vice President David Honeymeyer at Harrah's Las Vegas motivate his food and beverage employees. He said, "I try to emphasize the overall number, that we paid out half a million dollars last quarter to our people because we care about rewarding our employees. Two hundred dollars to one of my employees is not a lot of money, but it's symbolic, and the collective half a million dollars communicates that." Performance payouts at Harrah's St. Louis were, as in Las Vegas, an opportunity for symbolic confirmation of the company's goals. Ward Shaw recalled, "I would hand out the checks personally to all the slot employees at a big barbecue; there was a lot of excitement the first time, and the money does matter to the employees. We saw our turnover go down from 70% to under 50% in one year, and that was great for us. The challenge is to keep it fresh." Shaw had started at Harrah's St. Louis when it opened in March 1997. He had been hired into the "President's Associate Program," Satre's effort to bring MBAs into the organization. He worked in St. Louis under a well-respected general manager, Vern Jennings, who became a mentor to Shaw. Shaw rose quickly to the key role of director of slots, managing the key revenue stream for the property. He said Winn's corporate HR goals were certainly felt at the properties, especially because of the way manager bonuses were structured. Thirty percent of Shaw's bonus was dependent on employee feedback on two surveys: the employee opinion survey, where employees assessed the property and department; and the supervisory feedback survey, where employees assessed the specific supervisor. The makeup of Shaw's own bonus was 30% employee feedback on surveys, 40% customer service metrics, 20% financial goals, and 10% subjective/leadership. In the third quarter of 2001, employees at Harrah's Las Vegas achieved the levels needed for a bonus payout for the first time. Ed Rylant, vice president of slot operations, took a lot of pride in this, as slot's performance accounted for 30% of the property's results. He said, "Two years ago, Harrah's Las Vegas scores were floating in the bottom third of the properties. The two things I want to achieve this year are best in brand scores and breaking 99 seconds on how fast our employees get to our customers when called. We are at 105 seconds right now, which is already a big improvement from 360 seconds two years ago." At the same time, Rylant wanted managers to be not just numbersoriented task managers focused on the gain-sharing program but also relationship managers. He said, "The typical employee screams for change, but you start changing and then he or she doesn't like it. We have to help people understand why it's a good thing. Even if they don't always understand the specific changes, most of my employees would tell you they would never want to go back to the way the company was two years ago." Susie Lewis, director of cashiering at Rio's, was excited when the cashiers received a performance payout bonus in the previous year: "Valet had been beating us, but then we went past them in the customer satisfaction scores, and we were best on property. I tell my cashiers all the time, we're the best cashiers on the strip, let's stay number one." Lewis said in earlier quarters, it had been a letdown when they missed the bonus by a small margin. "We can't give them the money, but I went and made 403-008 Harrah's Entertainment, Inc.: Rewarding Our People 50 baseball shirts that said 'CAGE 2001,'2 which people liked. I have confidence in the process and in my team, so it's easy for me to get jazzed and tell them we really are going to get the bonus next time." Winn's Recommendation Harrah's Las Vegas was the only property in Las Vegas after September 11 that did not lay off a single employee. Its two most direct competitors, MGM Mirage and Park Place, laid off 6,000 people. While Harrah's business dipped for eight days, a month later it was at 94% occupancy at the Rio property and 90% at Harrah's Las Vegas. Drinking the last of her now cold cappuccino, Winn flipped through the Harrah's Entertainment, Inc. annual report, which had just arrived straight from the printer. The first eight pages were pictures of customers with tag lines such as "Joyce and Ted like oceanfront views, barbershop quartets, Elvis slots, and Harrah's Total Rewards," or "Pete likes fine cigars, hotel suites, Rolex watches, and Harrah's Total Rewards." The cover of the annual report proclaimed, "We know what our customers like." Winn wondered, when the annual report is all about our customers, how do we make sure employees feel valued? She had introduced gain sharing alongside the other strategic HR practices to tell her employees they were important. But the profit numbers were not where they should be, the economy was dragging, air travel might never recover from September 11, and Harrah's employees were thankful to just have jobs, let alone a bonus payout. But customer service was more important than ever as a distinguishing characteristic for Harrah's, so it was urgent to keep employees motivated. Was the bonus payout program an effective motivator, and if not, how should it be revised, or what should it be replaced with? She knew there was murmuring in the system by some employees that the goals were too aggressive and that some employees were tiring of the constant focus on achieving performance goals. Winn got up to leave the caf at the Rio, heading over to Loveman's office at headquarters, where he awaited her recommendation. Harrah's Entertainment, Inc.: Rewarding Our People Exhibit 1 Promortios onf Harrah's Iulv ono Exhibit 2 Slot Service Hire Guide-Realistic Job Preview Activity - Realistic Job Preview (RJP) Purpose - To provide candidate with as much information as possible about requirements and expectations of the job, including both positive and negative aspects, so that candidate can make an informed decision. - RJPs have been shown to reduce turnover by 40% compared to no preview at all and are better than written or video interviews for reducing turnover. Procedure - After department interview, candidate, who is still being considered for the job, is escorted to work area by supervisor or HR rep to observe job and talk with a high-performing employee or supervisor. - Candidate is NOT informed of actual hiring status at this time. - Candidates should strongly be encouraged to return during busiest slot play shifts. - Hint: Think of incentives that would bring them back such as offering them a small gift once they complete the visit. - Candidates should shadow as long as they can but not more than one hour and not less than 15 minutes. Resource Requirements - High-performing employee to present the RJP Measure of Success - Candidate will be asked to evaluate value of RJP (and entire hiring process) during 45-day checkup by HR. - Turnover rates will be assessed one month following implementation and compared with turnover rates prior to administration

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts