Question: How do you solve this with Python? The card that wins the trick def winning_card(cards, trump=None): Playing cards are again represented as tuples of (rank,

How do you solve this with Python?

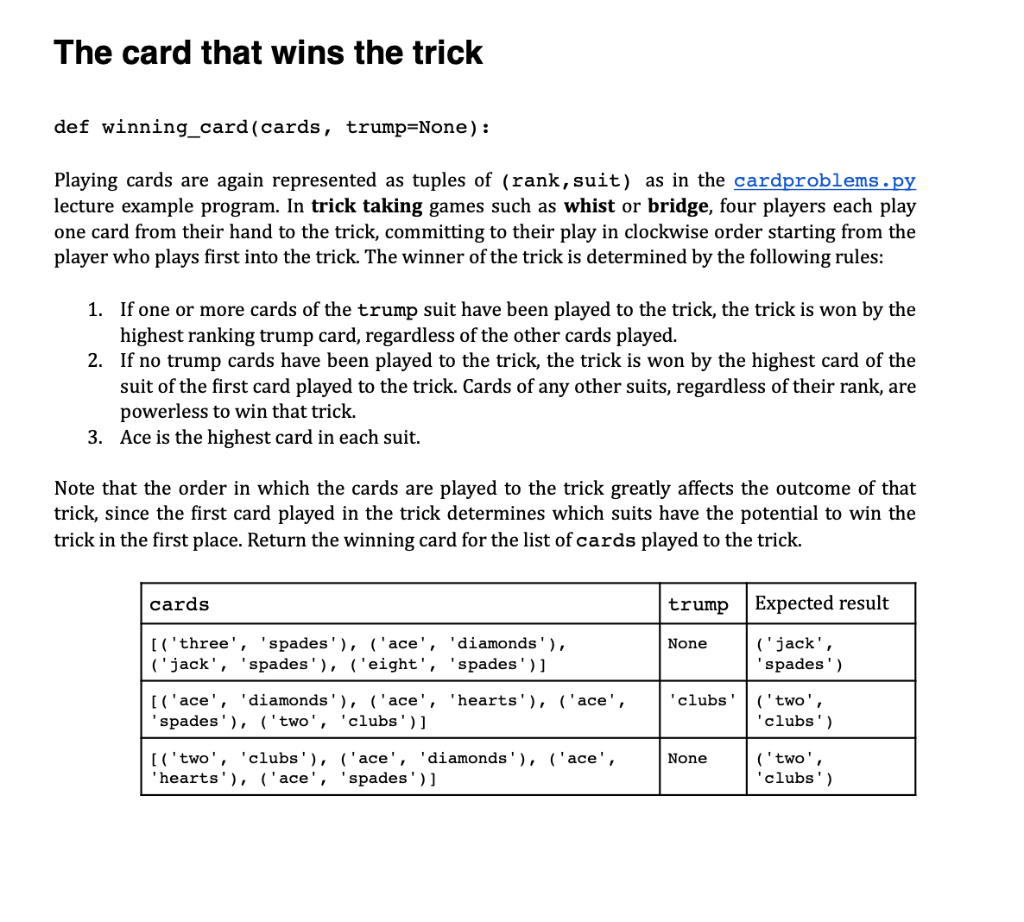

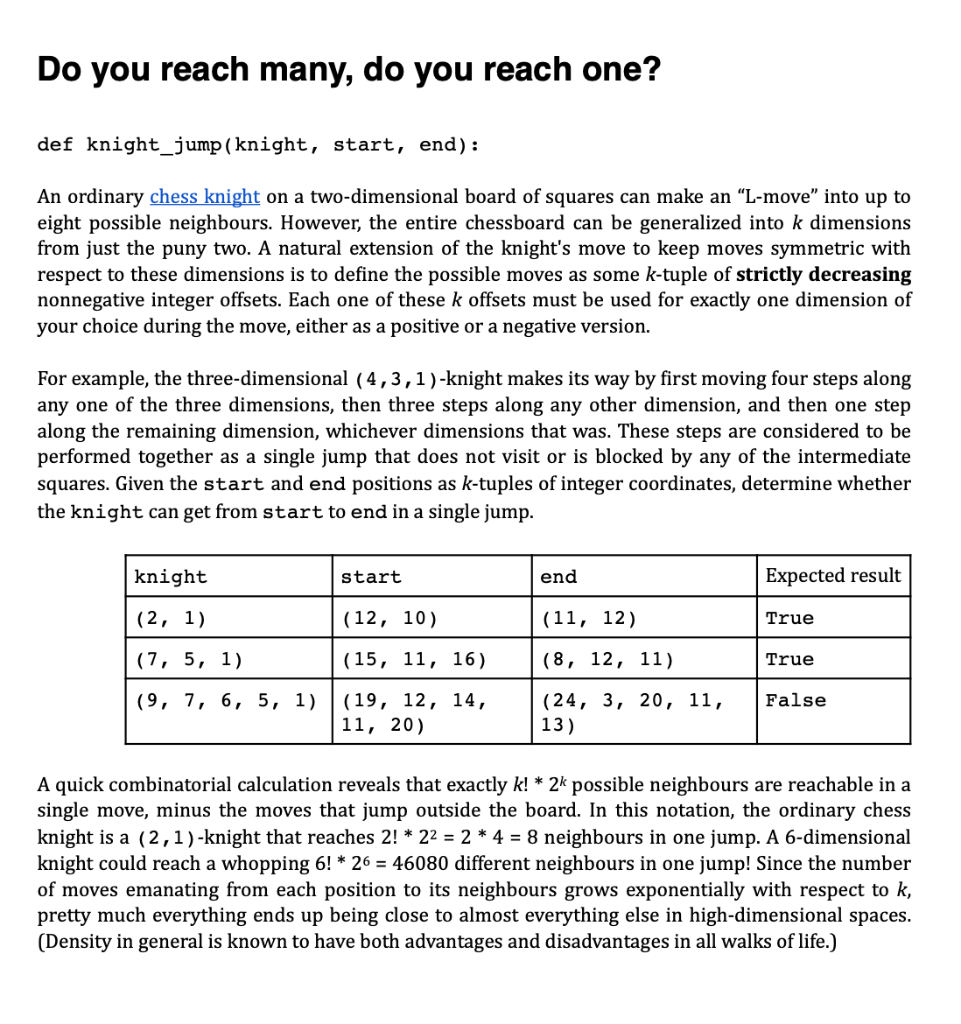

The card that wins the trick def winning_card(cards, trump=None): Playing cards are again represented as tuples of (rank, suit) as in the cardproblems.py lecture example program. In trick taking games such as whist or bridge, four players each play one card from their hand to the trick, committing to their play in clockwise order starting from the player who plays first into the trick. The winner of the trick is determined by the following rules: 1. If one or more cards of the trump suit have been played to the trick, the trick is won by the highest ranking trump card, regardless of the other cards played. 2. If no trump cards have been played to the trick, the trick is won by the highest card of the suit of the first card played to the trick. Cards of any other suits, regardless of their rank, are powerless to win that trick. 3. Ace is the highest card in each suit. Note that the order in which the cards are played to the trick greatly affects the outcome of that trick, since the first card played in the trick determines which suits have the potential to win the trick in the first place. Return the winning card for the list of cards played to the trick. cards trump Expected result None [('three', 'spades'), ('ace', 'diamonds'), ('jack', 'spades'), ('eight', 'spades')) ('jack', 'spades') [('ace', 'diamonds'), ('ace', 'spades'), ('two', 'clubs')] 'hearts'), ('ace', 'clubs ('two', 'clubs') None [('two', 'clubs'), ('ace', 'diamonds'), ('ace', 'hearts'), ('ace', spades')) ('two' . 'clubs') Do you reach many, do you reach one? def knight_jump (knight, start, end): An ordinary chess knight on a two-dimensional board of squares can make an L-move" into up to eight possible neighbours. However, the entire chessboard can be generalized into k dimensions from just the puny two. A natural extension of the knight's move to keep moves symmetric with respect to these dimensions is to define the possible moves as some k-tuple of strictly decreasing nonnegative integer offsets. Each one of these k offsets must be used for exactly one dimension of your choice during the move, either as a positive or a negative version. For example, the three-dimensional (4,3,1)-knight makes its way by first moving four steps along any one of the three dimensions, then three steps along any other dimension, and then one step along the remaining dimension, whichever dimensions that was. These steps are considered to be performed together as a single jump that does not visit or is blocked by any of the intermediate squares. Given the start and end positions as k-tuples of integer coordinates, determine whether the knight can get from start to end in a single jump. knight start end Expected result (2, 1) (12, 10) (11, 12) True (7, 5, 1) True (15, 11, 16) (19, 12, 14, 11, 20) (8, 12, 11) (24, 3, 20, 11, (9, 7, 6, 5, 1) False 13) A quick combinatorial calculation reveals that exactly k! * 2k possible neighbours are reachable in a single move, minus the moves that jump outside the board. In this notation, the ordinary chess knight is a (2,1)-knight that reaches 2!* 22 = 2 * 4 = 8 neighbours in one jump. A 6-dimensional knight could reach a whopping 6! * 26 = 46080 different neighbours in one jump! Since the number of moves emanating from each position to its neighbours grows exponentially with respect to k, pretty much everything ends up being close to almost everything else in high-dimensional spaces. (Density in general is known to have both advantages and disadvantages in all walks of life.)

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts