- How does Signodes structure compare to the general types of structures presented in Table 9-1 on page 252?

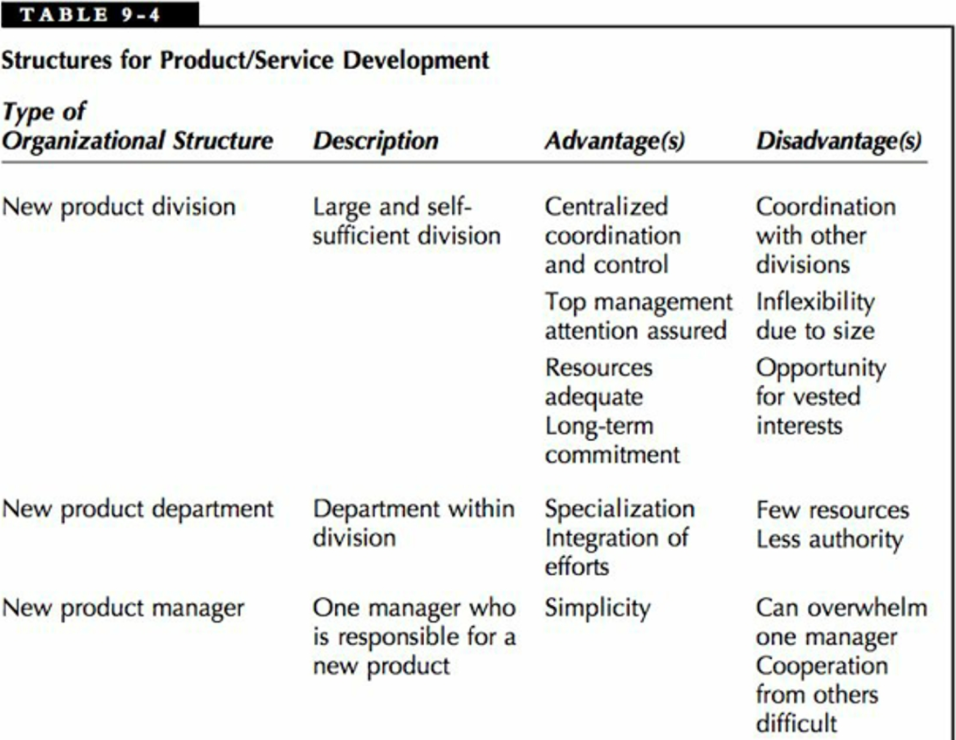

- What is the essence of the V-Team concept that makes it a component of the structures outlined in Table 9-4 on pages 261-262?

- Compare Signodes approach to venture development with the organizational design alternatives presented on pages 266-269.

Table 9-1 on page 252

-

-

-

- Table 9-4 on pages 261-262?

-

-

-

-

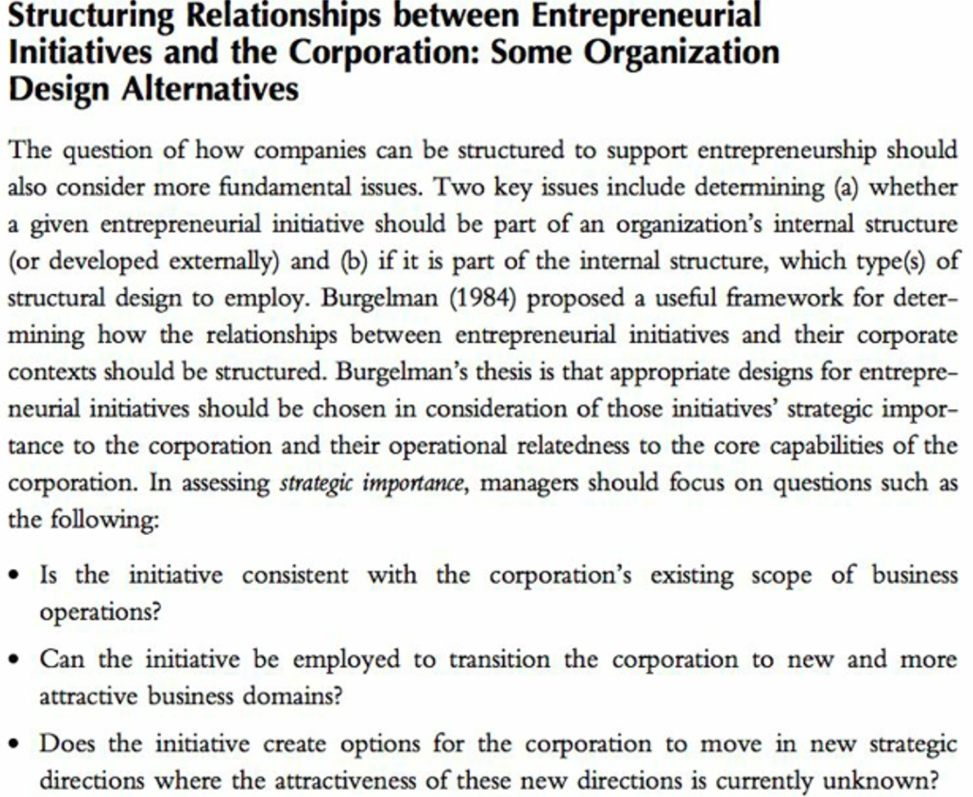

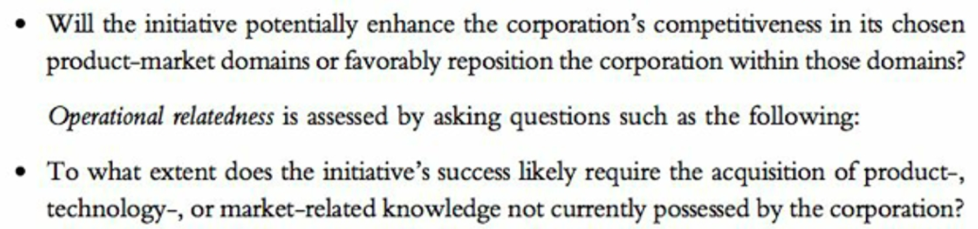

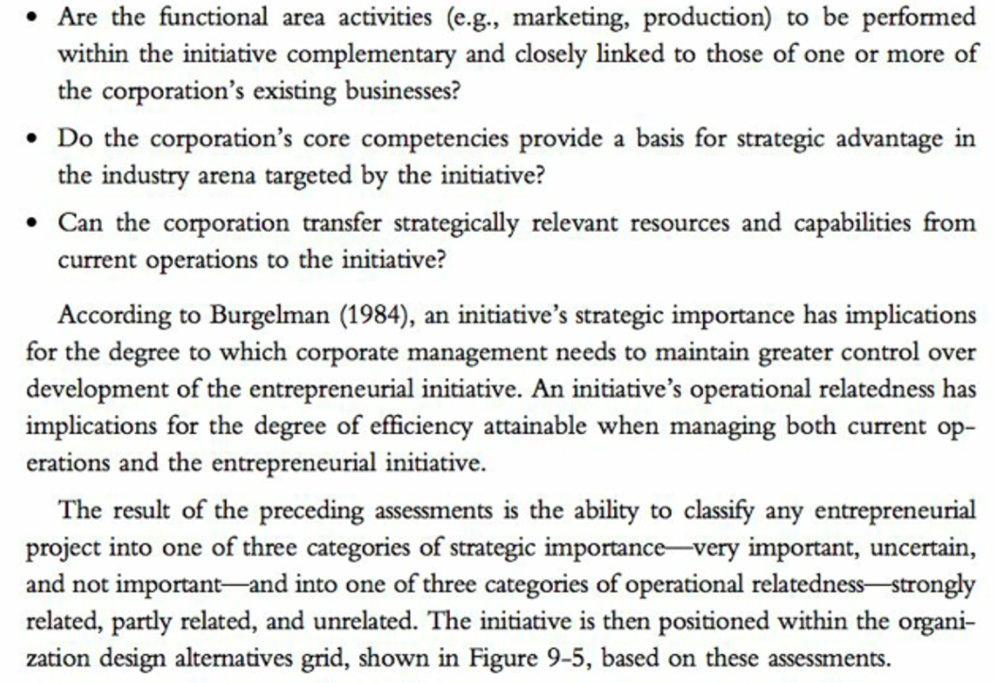

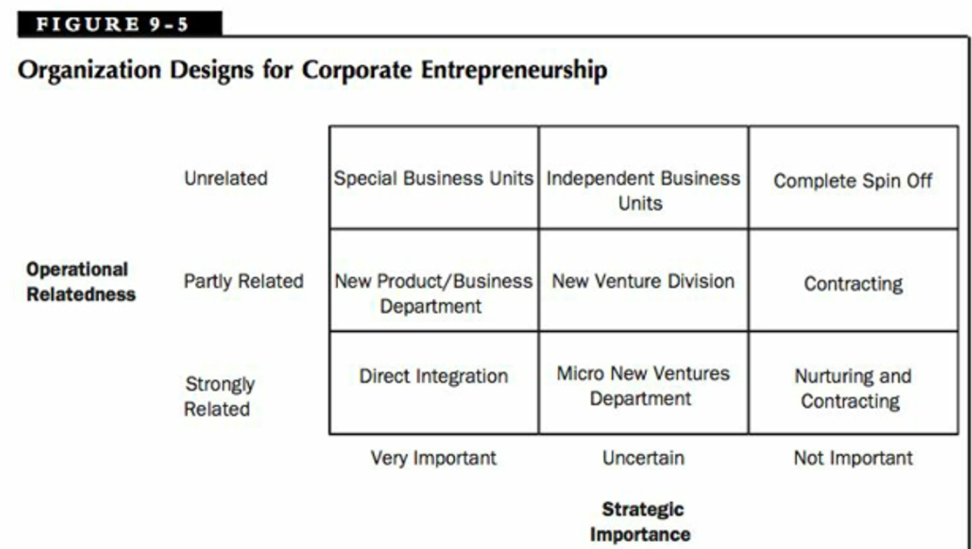

- Organizational design alternatives presented on pages 266-269.

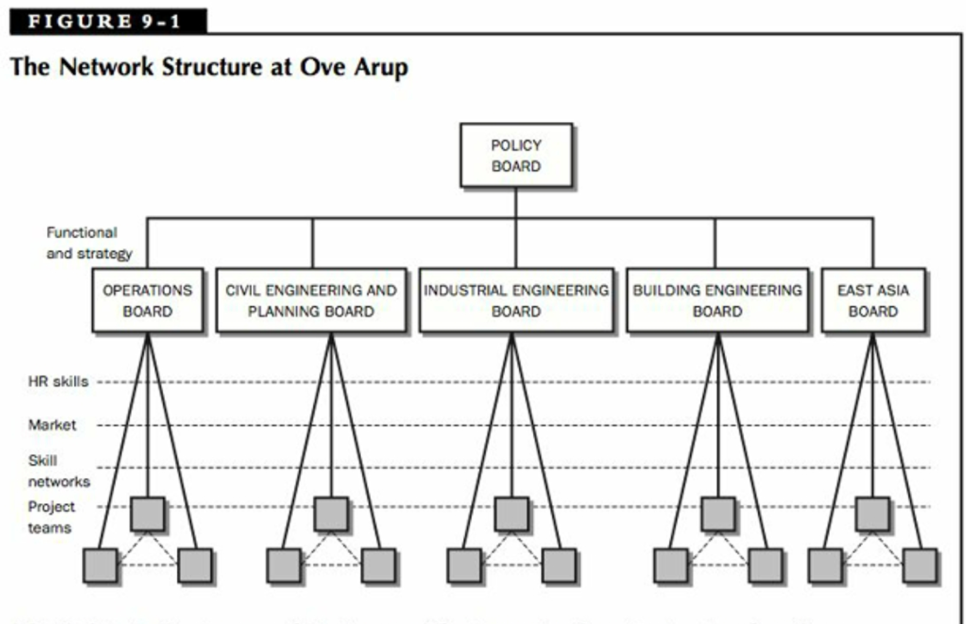

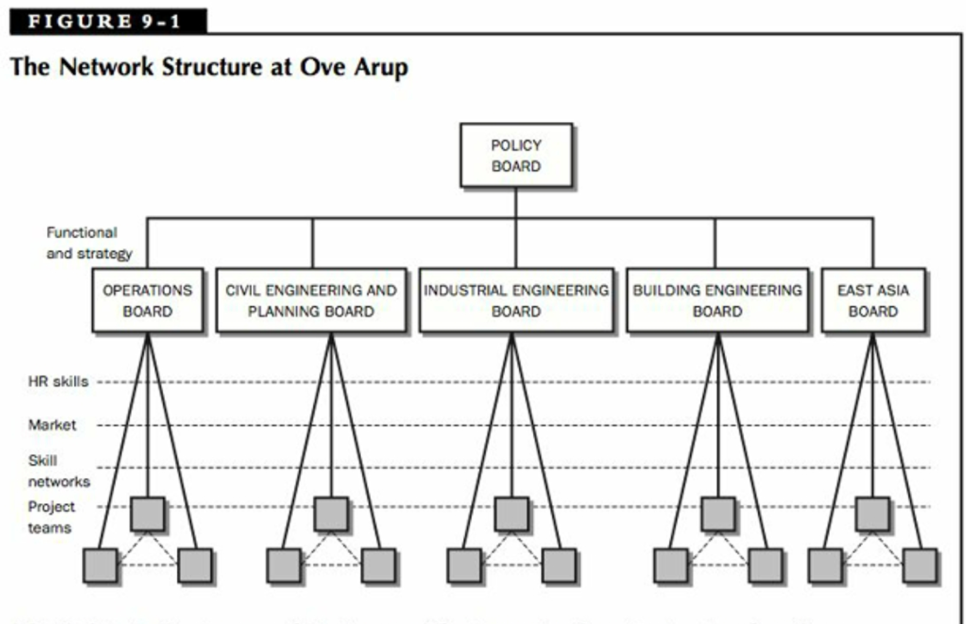

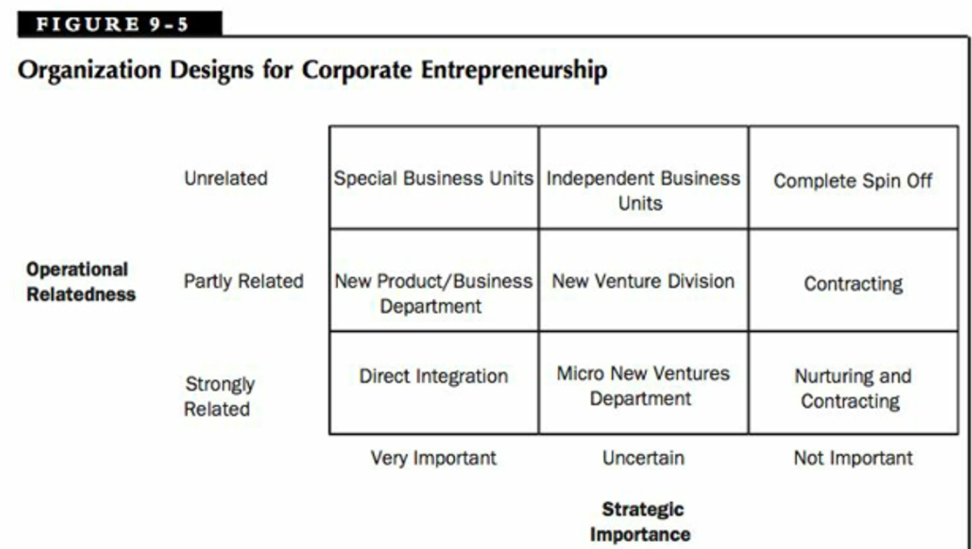

The Signode V-Team Structure Venture teams offer corporations the opportunity to capitalize on individual ta- lents together with collective wisdom and energy. A classic example from some years back was Signode, a $750-million-a-year manufacturer of plastic and steel strapping for packaging and materials handling, located in Glenview, Illinois. The company's leaders wanted to chart new directions to become a $1-billion-plus company. In pursuit of this goal, Signode devised an aggressive strategy for growth by developing new legs" for the company. It formed a cor- porate development group to pursue markets outside the company's core busi- ness but within the framework of its corporate strengths. It also formed venture teams, but before launching the first of these, top management identified the company's global business strengths and broad areas with potential for new product lines: warehousing/shipping; packaging; plastics for non-packaging, fastening, and joining systems; and product identification and control systems. Each new business opportunity suggested by a venture team was to have the potential to generate $50 million in business within five years. In addition, each opportunity had to build on one of Signode's strengths: industrial customer base and marketing expertise, systems sales and service capabilities, containment and reinforcement technology, steel and plastic process technology, machine and design capabilities, and production and distribution know-how. The assessment criteria were based on selling to business-to-business markets. The basic technol- ogy to be employed in the new business had to already exist, and there had to be a strong likelihood of attaining a major market share within a niche. Finally, the initial investment in the new opportunity had to be $30 million or less. Based on these criteria, Signode began to build its V-Team (venture team) approach to entrepreneurship. It took three months to select the first team members, and initial teams had three common traits: high risk-taking ability, creativity, and the ability to deal with ambiguity. All participants were multidis- ciplinary volunteers who would work full-time on developing new consumer product packaging businesses. The team members came from diverse back- grounds: design engineering, marketing, sales, and product development. They set up shop in rented office space five miles from the company's headquarters. Not all six teams were able to develop highly successful new ventures. However, the efforts did pay off for Signode as one venture team developed a business plan to manufacture plastic trays for frozen entrees that could be used in either regular or microwave ovens, which did indeed turn out to be a $50-million-a-year business within five years. The V-Team experience rekindled enthusiasm and affected moral throughout the organization. Most importantly, the V-Team approach became Signode's strategy to invent its own future rather than waiting for things to happen. FIGURE 9-1 The Network Structure at Ove Arup POLICY BOARD Functional and strategy OPERATIONS BOARD CIVIL ENGINEERING AND PLANNING BOARD INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING BOARD BUILDING ENGINEERING BOARD EAST ASIA BOARD HR skills Market Skill networks Project teams TABLE 9-4 Structures for Product/Service Development Type of Organizational Structure Description Advantage(s) Disadvantage(s) New product division Large and self Centralized Coordination sufficient division coordination with other and control divisions Top management Inflexibility attention assured due to size Resources Opportunity adequate for vested Long-term interests commitment New product department Department within Specialization Few resources division Integration of Less authority efforts New product manager One manager who Simplicity Can overwhelm is responsible for a one manager new product Cooperation from others difficult Structuring Relationships between Entrepreneurial Initiatives and the Corporation: Some Organization Design Alternatives The question of how companies can be structured to support entrepreneurship should also consider more fundamental issues. Two key issues include determining (a) whether a given entrepreneurial initiative should be part of an organization's internal structure (or developed externally) and (b) if it is part of the internal structure, which type(s) of structural design to employ. Burgelman (1984) proposed a useful framework for deter- mining how the relationships between entrepreneurial initiatives and their corporate contexts should be structured. Burgelman's thesis is that appropriate designs for entrepre- neurial initiatives should be chosen in consideration of those initiatives' strategic impor- tance to the corporation and their operational relatedness to the core capabilities of the corporation. In assessing strategic importance, managers should focus on questions such as the following: Is the initiative consistent with the corporation's existing scope of business operations? Can the initiative be employed to transition the corporation to new and more attractive business domains? Does the initiative create options for the corporation to move in new strategic directions where the attractiveness of these new directions is currently unknown? Will the initiative potentially enhance the corporation's competitiveness in its chosen product-market domains or favorably reposition the corporation within those domains? Operational relatedness is assessed by asking questions such as the following: To what extent does the initiative's success likely require the acquisition of product-, technology-, or market-related knowledge not currently possessed by the corporation? Are the functional area activities (e.g., marketing, production) to be performed within the initiative complementary and closely linked to those of one or more of the corporation's existing businesses? Do the corporation's core competencies provide a basis for strategic advantage in the industry arena targeted by the initiative? Can the corporation transfer strategically relevant resources and capabilities from current operations to the initiative? According to Burgelman (1984), an initiative's strategic importance has implications for the degree to which corporate management needs to maintain greater control over development of the entrepreneurial initiative. An initiative's operational relatedness has implications for the degree of efficiency attainable when managing both current op- erations and the entrepreneurial initiative. The result of the preceding assessments is the ability to classify any entrepreneurial project into one of three categories of strategic importancevery important, uncertain, and not importantand into one of three categories of operational relatednessstrongly related, partly related, and unrelated. The initiative is then positioned within the organi- zation design alternatives grid, shown in Figure 9-5, based on these assessments. FIGURE 9-5 Organization Designs for Corporate Entrepreneurship Unrelated Special Business Units Independent Business Units Complete Spin Off Operational Relatedness Partly Related New Product/Business New Venture Division Department Contracting Direct Integration Strongly Related Micro New Ventures Department Nurturing and Contracting Very Important Uncertain Not Important Strategic Importance Nine distinct design possibilities are suggested. A corporation is not limited to the use of one of these designs. Rather, the company could employ as many of them as is warranted by the diversity of their entrepreneurial initiatives. The possible organization designs or structures include: Direct integration (high strategic importance, strong operational relatedness): The entrepreneurial initiative is pursued within the mainstream operations of the corporation. New product/business department (high strategic importance, partial operational relat- edness): A separate department for the entrepreneurial initiative is created in that part of the corporation (division or group) where significant potential exists for sharing capabilities and skills. Separate business units (high strategic importance, low operational relatedness): A spe- cially dedicated and operationally distinct unit is created inside the corporate struc- ture to house the entrepreneurial initiative. Micro new ventures department (uncertain strategic importance, strong operational re- latedness): An organizational unit is created where autonomously emerging en- trepreneurial initiatives are pursued without the constraint of currently having to fit with the corporation's strategy. New venture division (uncertain strategic importance, partial operational relatedness): An organizational division is designed to house a wide range of potentially interest- ing entrepreneurial initiatives that are of ambiguous fit with the corporation. Independent business units (uncertain strategic importance, low operational related- ness): A specially dedicated and operationally distinct unit is created outside the cor- porate structure to house the entrepreneurial initiative. Nurturing plus contracting (low strategic importance, strong operational relatedness): The corporation's knowledge and competencies are leveraged in entrepreneurial in- itiatives that are moved outside the corporate structure (e.g., outsourcing some part of the entrepreneurial project) and in which that knowledge or those competencies constitute strategic assets for the initiative. Contracting (low strategic importance, partial operational relatedness): The corpora- tion's knowledge and competencies are leveraged in entrepreneurial initiatives that are moved outside the corporate structure (by contracting to some outside organi- zation) and in which that knowledge or those competencies add some value to the initiative's operations. Complete spin off (low strategic importance, low operational relatedness): The total separation of the entrepreneurial initiative from the corporation. Thus, a key premise of Burgelman's (1984) design alternatives framework is that not all entrepreneurial initiatives are the same, and this fact must be reflected in the specific attributes of the structures employed to house those initiatives. A one-size-fits-all men- tality with respect to structuring for entrepreneurship won't work. The Signode V-Team Structure Venture teams offer corporations the opportunity to capitalize on individual ta- lents together with collective wisdom and energy. A classic example from some years back was Signode, a $750-million-a-year manufacturer of plastic and steel strapping for packaging and materials handling, located in Glenview, Illinois. The company's leaders wanted to chart new directions to become a $1-billion-plus company. In pursuit of this goal, Signode devised an aggressive strategy for growth by developing new legs" for the company. It formed a cor- porate development group to pursue markets outside the company's core busi- ness but within the framework of its corporate strengths. It also formed venture teams, but before launching the first of these, top management identified the company's global business strengths and broad areas with potential for new product lines: warehousing/shipping; packaging; plastics for non-packaging, fastening, and joining systems; and product identification and control systems. Each new business opportunity suggested by a venture team was to have the potential to generate $50 million in business within five years. In addition, each opportunity had to build on one of Signode's strengths: industrial customer base and marketing expertise, systems sales and service capabilities, containment and reinforcement technology, steel and plastic process technology, machine and design capabilities, and production and distribution know-how. The assessment criteria were based on selling to business-to-business markets. The basic technol- ogy to be employed in the new business had to already exist, and there had to be a strong likelihood of attaining a major market share within a niche. Finally, the initial investment in the new opportunity had to be $30 million or less. Based on these criteria, Signode began to build its V-Team (venture team) approach to entrepreneurship. It took three months to select the first team members, and initial teams had three common traits: high risk-taking ability, creativity, and the ability to deal with ambiguity. All participants were multidis- ciplinary volunteers who would work full-time on developing new consumer product packaging businesses. The team members came from diverse back- grounds: design engineering, marketing, sales, and product development. They set up shop in rented office space five miles from the company's headquarters. Not all six teams were able to develop highly successful new ventures. However, the efforts did pay off for Signode as one venture team developed a business plan to manufacture plastic trays for frozen entrees that could be used in either regular or microwave ovens, which did indeed turn out to be a $50-million-a-year business within five years. The V-Team experience rekindled enthusiasm and affected moral throughout the organization. Most importantly, the V-Team approach became Signode's strategy to invent its own future rather than waiting for things to happen. FIGURE 9-1 The Network Structure at Ove Arup POLICY BOARD Functional and strategy OPERATIONS BOARD CIVIL ENGINEERING AND PLANNING BOARD INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING BOARD BUILDING ENGINEERING BOARD EAST ASIA BOARD HR skills Market Skill networks Project teams TABLE 9-4 Structures for Product/Service Development Type of Organizational Structure Description Advantage(s) Disadvantage(s) New product division Large and self Centralized Coordination sufficient division coordination with other and control divisions Top management Inflexibility attention assured due to size Resources Opportunity adequate for vested Long-term interests commitment New product department Department within Specialization Few resources division Integration of Less authority efforts New product manager One manager who Simplicity Can overwhelm is responsible for a one manager new product Cooperation from others difficult Structuring Relationships between Entrepreneurial Initiatives and the Corporation: Some Organization Design Alternatives The question of how companies can be structured to support entrepreneurship should also consider more fundamental issues. Two key issues include determining (a) whether a given entrepreneurial initiative should be part of an organization's internal structure (or developed externally) and (b) if it is part of the internal structure, which type(s) of structural design to employ. Burgelman (1984) proposed a useful framework for deter- mining how the relationships between entrepreneurial initiatives and their corporate contexts should be structured. Burgelman's thesis is that appropriate designs for entrepre- neurial initiatives should be chosen in consideration of those initiatives' strategic impor- tance to the corporation and their operational relatedness to the core capabilities of the corporation. In assessing strategic importance, managers should focus on questions such as the following: Is the initiative consistent with the corporation's existing scope of business operations? Can the initiative be employed to transition the corporation to new and more attractive business domains? Does the initiative create options for the corporation to move in new strategic directions where the attractiveness of these new directions is currently unknown? Will the initiative potentially enhance the corporation's competitiveness in its chosen product-market domains or favorably reposition the corporation within those domains? Operational relatedness is assessed by asking questions such as the following: To what extent does the initiative's success likely require the acquisition of product-, technology-, or market-related knowledge not currently possessed by the corporation? Are the functional area activities (e.g., marketing, production) to be performed within the initiative complementary and closely linked to those of one or more of the corporation's existing businesses? Do the corporation's core competencies provide a basis for strategic advantage in the industry arena targeted by the initiative? Can the corporation transfer strategically relevant resources and capabilities from current operations to the initiative? According to Burgelman (1984), an initiative's strategic importance has implications for the degree to which corporate management needs to maintain greater control over development of the entrepreneurial initiative. An initiative's operational relatedness has implications for the degree of efficiency attainable when managing both current op- erations and the entrepreneurial initiative. The result of the preceding assessments is the ability to classify any entrepreneurial project into one of three categories of strategic importancevery important, uncertain, and not importantand into one of three categories of operational relatednessstrongly related, partly related, and unrelated. The initiative is then positioned within the organi- zation design alternatives grid, shown in Figure 9-5, based on these assessments. FIGURE 9-5 Organization Designs for Corporate Entrepreneurship Unrelated Special Business Units Independent Business Units Complete Spin Off Operational Relatedness Partly Related New Product/Business New Venture Division Department Contracting Direct Integration Strongly Related Micro New Ventures Department Nurturing and Contracting Very Important Uncertain Not Important Strategic Importance Nine distinct design possibilities are suggested. A corporation is not limited to the use of one of these designs. Rather, the company could employ as many of them as is warranted by the diversity of their entrepreneurial initiatives. The possible organization designs or structures include: Direct integration (high strategic importance, strong operational relatedness): The entrepreneurial initiative is pursued within the mainstream operations of the corporation. New product/business department (high strategic importance, partial operational relat- edness): A separate department for the entrepreneurial initiative is created in that part of the corporation (division or group) where significant potential exists for sharing capabilities and skills. Separate business units (high strategic importance, low operational relatedness): A spe- cially dedicated and operationally distinct unit is created inside the corporate struc- ture to house the entrepreneurial initiative. Micro new ventures department (uncertain strategic importance, strong operational re- latedness): An organizational unit is created where autonomously emerging en- trepreneurial initiatives are pursued without the constraint of currently having to fit with the corporation's strategy. New venture division (uncertain strategic importance, partial operational relatedness): An organizational division is designed to house a wide range of potentially interest- ing entrepreneurial initiatives that are of ambiguous fit with the corporation. Independent business units (uncertain strategic importance, low operational related- ness): A specially dedicated and operationally distinct unit is created outside the cor- porate structure to house the entrepreneurial initiative. Nurturing plus contracting (low strategic importance, strong operational relatedness): The corporation's knowledge and competencies are leveraged in entrepreneurial in- itiatives that are moved outside the corporate structure (e.g., outsourcing some part of the entrepreneurial project) and in which that knowledge or those competencies constitute strategic assets for the initiative. Contracting (low strategic importance, partial operational relatedness): The corpora- tion's knowledge and competencies are leveraged in entrepreneurial initiatives that are moved outside the corporate structure (by contracting to some outside organi- zation) and in which that knowledge or those competencies add some value to the initiative's operations. Complete spin off (low strategic importance, low operational relatedness): The total separation of the entrepreneurial initiative from the corporation. Thus, a key premise of Burgelman's (1984) design alternatives framework is that not all entrepreneurial initiatives are the same, and this fact must be reflected in the specific attributes of the structures employed to house those initiatives. A one-size-fits-all men- tality with respect to structuring for entrepreneurship won't work