Question: In Algebra 2, you learned several different methods for solving quadratic equations. For example, you could try factoring, completing the square, or just use the

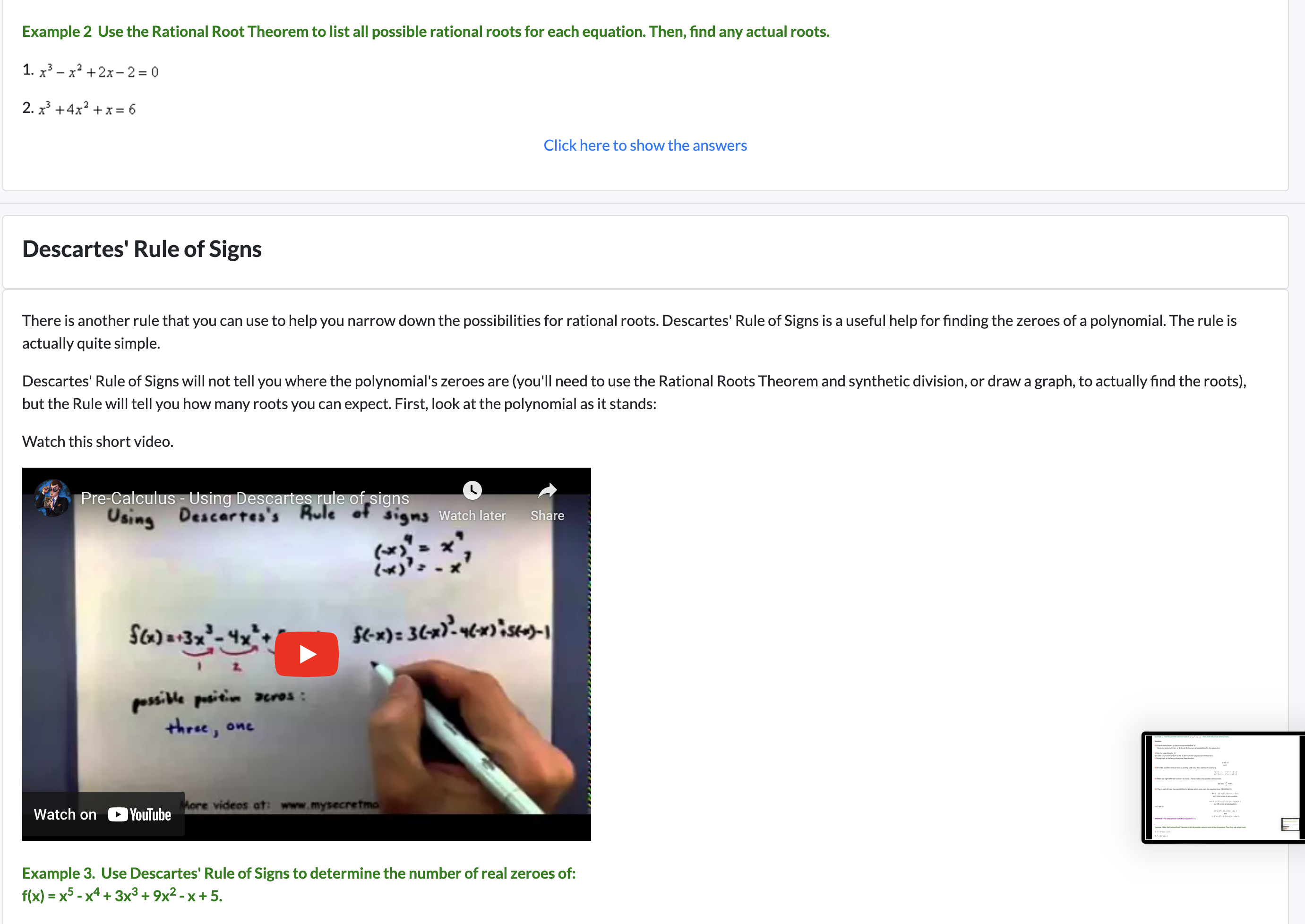

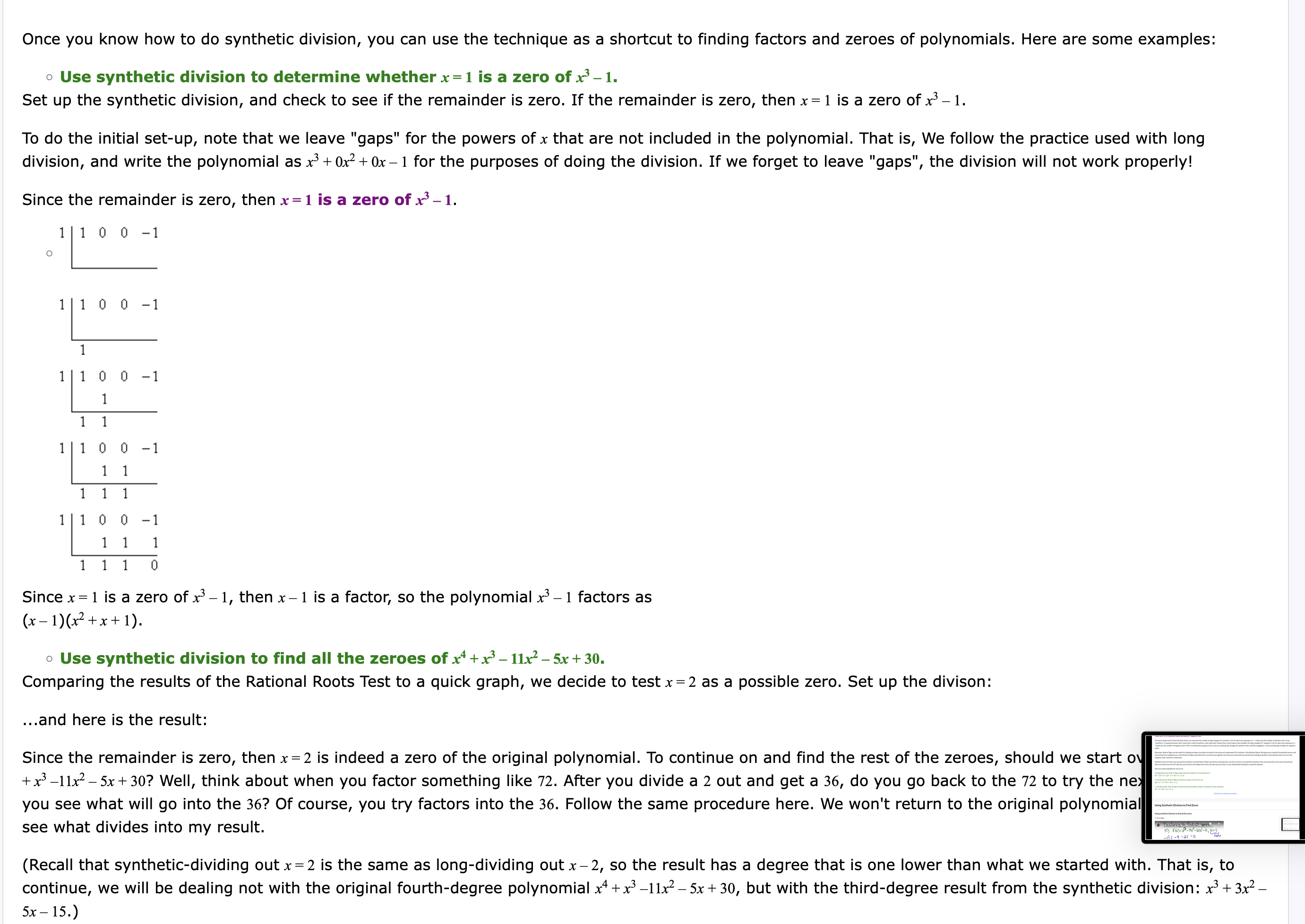

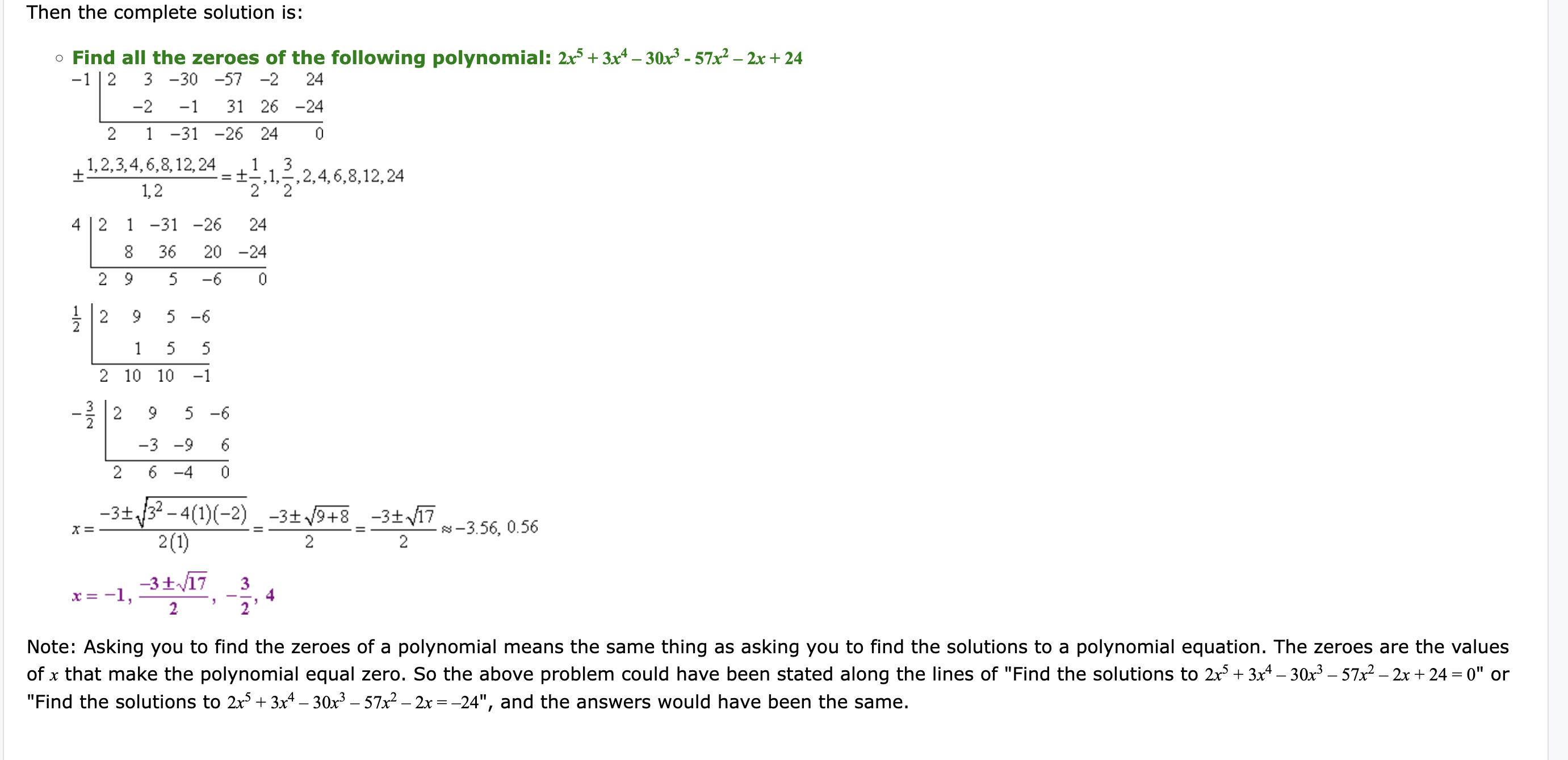

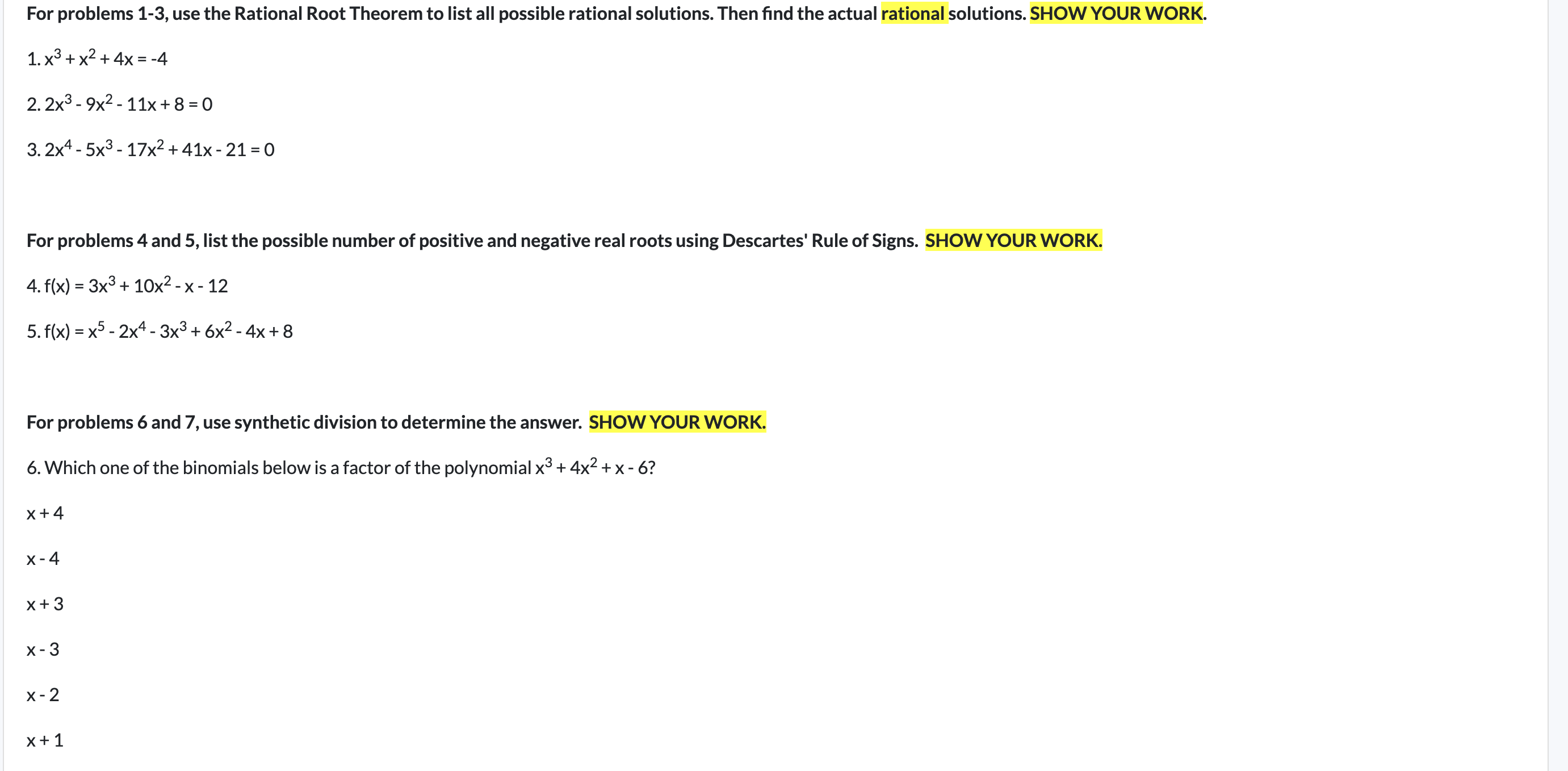

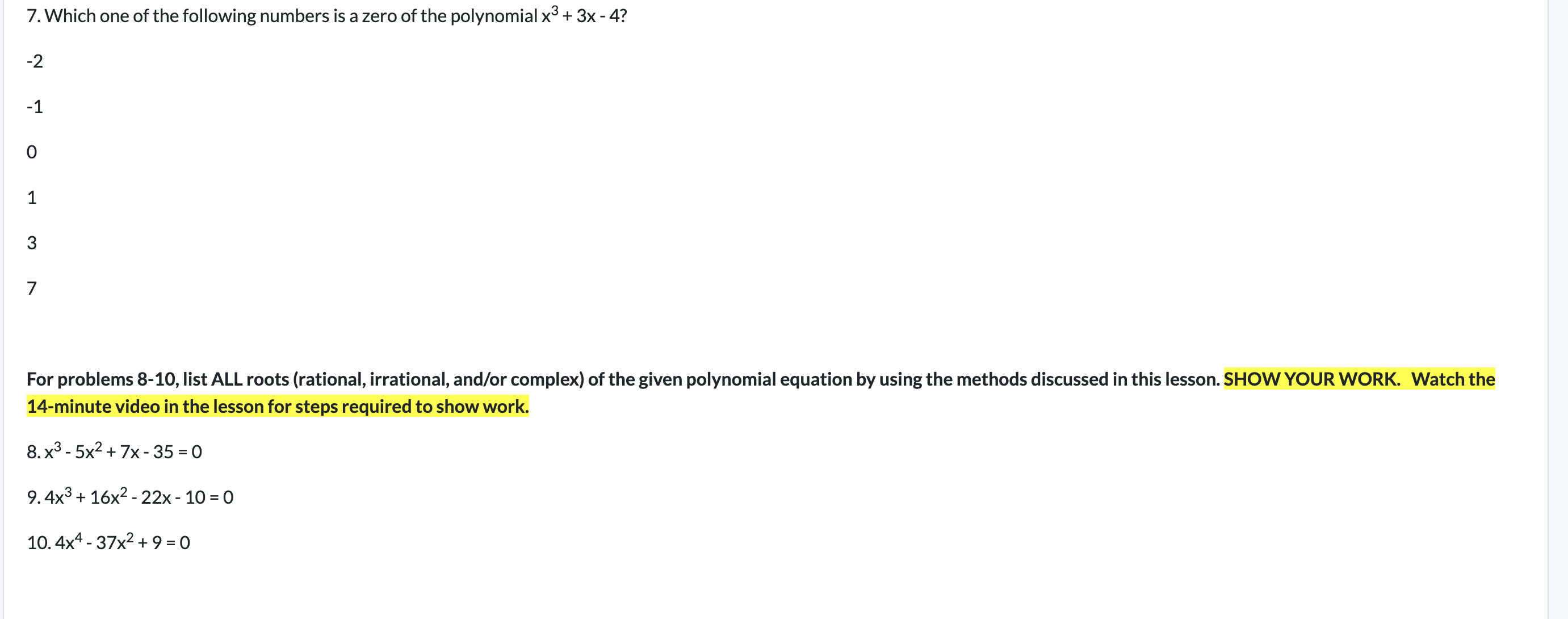

In Algebra 2, you learned several different methods for solving quadratic equations. For example, you could try factoring, completing the square, or just use the quadratic formula since it ALWAYS works. Now, you will learn to solve polynomial equations that have degrees higher than two. Unfortunately, when solving polynomial equations of higher degree, there are no "easy" methods (like factoring) or "sure-things" (like the quadratic formula). Instead, you basically have to start by making some guesses and checking to see if they work. But how do you know what to guess first? Fundamental theorem of algebra, theorem of equations proved by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1799, states that every polynomial equation of degree n with complex number coefficients has n roots, or solutions, in the complex numbers. The roots can have a multiplicity greater than zero. Example: polynomial of degree 5 has 5 roots or solutions The Rational Root Theorem For any polynomial equation with a degree of three or greater, the best way to start solving is to use the Rational Root Theorem, which will give you a list of possible zeros, or solutions, to the equation. The numbers you get from the Rational Root Theorem are not all necessarily solutions to the equation. In fact, it is possible that none of these numbers will solve the equation. The theorem is useful, however, because it tells you which numbers to try first. The Rational Root Theorem says that if p/q is in simplest form and is a root of a polynomial equation with integer coefficients, then p must be a factor of the constant term and g must be a factor of the leading coefficient. watch this 5-minute video: Watchilate Share a X =3x-1x + c Rational Roots Test /Theorem o 4y Example 1. Find the possible rational roots of x? 4+ x? 3x =3. Then, find the actual rational roots. Solution: S1 List all of the factors of the constant term to find "p." Since the factors of -3 are 1, -1, 3, and -3, these are all possibilities for the values of p. S2 Do the same thing for "q." Since the only factors of 1 are 1 and -1, these are the only two possibilities for g. S3 Keep track of the factors by writing them like this: S4 Find the possible rational roots by putting each value for p over each value for q. +1 1 =1 =1 3 +3 3 -3 +1-1+17-174+1"-1741" -1 S5 There are eight different numbers to check. These are the only possible rational roots. like this: f +143, S6 Plugin each of these four possibilities for x to see which ones make the equation true, MEANING = 0. X=1 MP+@*-31)=1+1-3=23 so 1isnot aroot of our equation. x=-1 (=D)>+(-1)*-3(-1)=-1+1+3=3 so-11S aroot of our equation. x=3and-3: GP+(3)?-3(H=27+9-9=3 and -9+ (=32 -3(-3)=-27+9+9%3 ANSWER" The only rational root of our equation is -1. Example 2 Use the Rational Root Theorem to list all possible rational roots for each equation. Then, find any actual roots. L -x?+2x-2=0 2.2 +4x +x=6 At bsss e kel sosmsmm s Example 2 Use the Rational Root Theorem to list all possible rational roots for each equation. Then, find any actual roots. 13-z +2x-2=0 2.2 +4x* +x=6 Click here to show the answers Descartes' Rule of Signs There is another rule that you can use to help you narrow down the possibilities for rational roots. Descartes' Rule of Signs is a useful help for finding the zeroes of a polynomial. The rule is actually quite simple. Descartes' Rule of Signs will not tell you where the polynomial's zeroes are (you'll need to use the Rational Roots Theorem and synthetic division, or draw a graph, to actually find the roots), but the Rule will tell you how many roots you can expect. First, look at the polynomial as it stands: Watch this short video. [[alefDI=Iex: it cartes's Watch on @ VYouTube Example 3. Use Descartes' Rule of Signs to determine the number of real zeroes of: f(x)=x5-x%+3x3 + 9x2-x +5. Example 3. Use Descartes' Rule of Signs to determine the number of real zeroes of: f(x)=x5-x%+3x3 + 9x2-x +5. Solution: f)=x"-x*+32+W?-x+5 Ignoring the actual values of the coefficients, look at the signs: fO)=+F-x'+3x3+ 92 -x+5 Now note where the signs change from positive to negative or from negative to positive: @)= - +33+%2-x+5 Count the number of changes: @)=+ - +3%3+ W% x+5 Y% 3y There are four sign changes. This number "four" is the maximum possible number of zeroes (x-intercepts) for the polynomial f(x) = x> - x* + 3x3 + 9x2 - x + 5. However, remember that some of the roots may be generated by the Quadratic Formula, and these pairs of roots may be complex. Then it may be that certain pairs of roots are not real, and therefore are not graphable as x- intercepts. Because of this possibility, you have to count down by two's. That is, while there may be as many as four real zeroes, there might also be only two, and there might also be zero (none atall). Now look at f(-x): Flox) = (=2) = ()" + 3(=x)* + 9P = (x) + 5 =xf-xi-3xP+ WP x+5 Look at the signs: flx)=x3x -3+ 92+ x+5 Count the number of sign changes: flEx)y==x5 -2 \\3,;3/+ M2 +x+5 There is only one sign change, so there is exactly one negative root. In this case, you don't count down by two's, because you would end up with a negative number. There are 4, 2, or 0 positive roots, and exactly 1 negative root. The way to keep track of how this Rule works is to note that the number of sign changes for "positive" x (or for when you evaluate at x = +1) give you the number of positive roots. (I say "'positive' X" in quotes because | don't mean that x itself is positive; | only mean that | haven't put a minus sign on the variable.) The sign changes for "negative" x (or for when you evaluate at x = -1) give you the number of negative roots. There is nothing fancy going on here: you are counting sign changes for positive roots, and then plugging in -x and counting sign changes for negative rantc There are 4, 2, or 0 positive roots, and exactly 1 negative root. The way to keep track of how this Rule works is to note that the number of sign changes for "positive" x (or for when you evaluate at x = +1) give you the number of positive roots. (I say "'positive' X" in quotes because | don't mean that x itself is positive; | only mean that | haven't put a minus sign on the variable.) The sign changes for "negative" x (or for when you evaluate at x = -1) give you the number of negative roots. There is nothing fancy going on here: you are counting sign changes for positive roots, and then plugging in -x and counting sign changes for negative roots. Descartes' Rule of Signs can be useful for helping you figure out where to look for the zeroes of a polynomial. For instance, if the Rational Roots Test gives you a long list of potential zeroes, and you've found one negative zero, and the Rule of Signs says that there is at most one negative root, then you know that you should start looking at positive roots, because there are no more negative roots, rational or otherwise. Similarly, if you've found, say, two positive solutions, and the Rule of Signs says that you should have, say, five or three or one positive solutions, then you know that, since you've found two, there is at least one more (to take you up to three), and maybe three more (to take you up to five), so you should keep looking for a positive solution. Here are some examples for you to try. 3.Using Descartes' Rule of Signs, determine the number of real solutions to 4x7+3x6+ x5+ 2x*-x3+ 9x2 + x+ 1=0. 4. Use Descartes' Rule of Signs to find the number of real roots of fx) =x5+x*+ 43+ 32+ x+ 1. 5.Use Descartes' Rule of Signs to determine the possible number of solutions to the equation 2x*-x3+4x2-5x+3=0. Click here to show the answers Using Synthetic Division to Find Zeros Using synthetic division to find all the zeros 3-minvideo Once you know how to do synthetic division, you can use the technique as a shortcut to finding factors and zeroes of polynomials. Here are some examples: o Use synthetic division to determine whether x=1 is a zero of x*-1. Set up the synthetic division, and check to see if the remainder is zero. If the remainder is zero, then x=1 is a zero of x> 1. To do the initial set-up, note that we leave "gaps" for the powers of x that are not included in the polynomial. That is, We follow the practice used with long division, and write the polynomial as x*+ 0x? + 0x 1 for the purposes of doing the division. If we forget to leave "gaps", the division will not work properly! Since the remainder is zero, then x=1 is a zero of x*-1. 111 0 0 -1 o 111 0 0 -1 1 111 0 0 -1 1 11 111 0 0 -1 11 111 1110 0 -1 11 1 111 0 Since x=1 is a zero of x* -1, then x1 is a factor, so the polynomial x* 1 factors as (x-1)(2+x+1). o Use synthetic division to find all the zeroes of x* + x* 11x? - 5x + 30. Comparing the results of the Rational Roots Test to a quick graph, we decide to test x=2 as a possible zero. Set up the divison: ...and here is the result: Since the remainder is zero, then x=2 is indeed a zero of the original polynomial. To continue on and find the rest of the zeroes, should we start o +x> 11x2 - 5x + 30? Well, think about when you factor something like 72. After you divide a 2 out and get a 36, do you go back to the 72 to try the ne you see what will go into the 36? Of course, you try factors into the 36. Follow the same procedure here. We won't return to the original polynomialfff - see what divides into my result. (Recall that synthetic-dividing out x=2 is the same as long-dividing out x -2, so the result has a degree that is one lower than what we started with. That is, to continue, we will be dealing not with the original fourth-degree polynomial x* + x> -11x2 5x + 30, but with the third-degree result from the synthetic division: x> +3x% - 5x15.) o Use synthetic division to find all the zeroes of x* +x 11x* 5x + 30. Comparing the results of the Rational Roots Test to a quick graph, we decide to test x=2 as a possible zero. Set up the divison: ...and here is the result: Since the remainder is zero, then x=2 is indeed a zero of the original polynomial. To continue on and find the rest of the zeroes, should we start over again with x* +x3 11x2 - 5x + 30? Well, think about when you factor something like 72. After you divide a 2 out and get a 36, do you go back to the 72 to try the next factor, or do you see what will go into the 36? Of course, you try factors into the 36. Follow the same procedure here. We won't return to the original polynomial, but will instead see what divides into my result. (Recall that synthetic-dividing out x=2 is the same as long-dividing out x -2, so the result has a degree that is one lower than what we started with. That is, to continue, we will be dealing not with the original fourth-degree polynomial x* + x> ~11x2 5x + 30, but with the third-degree result from the synthetic division: x> +3x% - 5x15.) Continuing, and again comparing the Rational Roots Test with a quick graph, we will try x=-3. Set up the division: ...and here is the result: Since the remainder is zero, then x=-3 is a zero of the original polynomial. At this point, the final result is a quadratic, (x**5), and we can apply the Quadratic Formula or other methods to get the remaining zeroes: Then all the zeroes are: _3 +.5 2 2|1 1 -11 -5 30 2|1 1 -11 -5 30 2 6 -10 -30 13 -5 -15 0 211 1 -11 -5 30 2 6 -10 -30 =311 3 =5 =15 0 2 6 -10 -30 =3|11 3 -5 =15 0 x=i x2-5=0 =5 x=iJ This is how synthetic division is usually used. You try various zeroes until one works, and then you try zeroes on the result until something works, and you keep on going like this until you get down to a quadratic, at which point you use the Quadratic Formula or other methods to get the last two zeroes. Watch this 14-minute video demonstrating how to apply all the concepts in this lesson to find the solutions of polynomial equations with higher degrees: () PRRsand solutions a4l 1ix? aexe 920 . Step 3 Use synthetic division to to get a depressed Step 1 Determine all possible rational roots. polynomial. Petl 39) 4 ihralisy Step2 Use Remainder Theorem to find the first root. o Sie .4 Start the process over again with the depressed polynomial. Upper and Lower Bounds for Real Zeros Do you really have to try all the possible roots that the Rational Roots Test might spit out? Not necessarily. There are a couple tricks you can use when working with synthetic division and the Rational Roots Test. Here's an example: o Find all the roots of 2x* + 7x* - 16x + 6. The Rational Roots Test gives the following list of possible zeroes: Upper and Lower Bounds for Real Zeros Do you really have to try all the possible roots that the Rational Roots Test might spit out? Not necessarily. There are a couple tricks you can use when working with synthetic division and the Rational Roots Test. Here's an example: o Find all the roots of 2x* + 7x* - 16x + 6. The Rational Roots Test gives the following list of possible zeroes: y For comparison, here is what the graph looks like: As you can see, there are no x-intercepts before x =6 nd no x-intercepts after x=2. We would guess that the zeroes are a little before x=-5, right at x="1/,, and a little after x=1. We would guess that the rational zero will be at x=/,, and the other two zeroes will be irrational, generated by the square root in the Quadratic Formula. But if you don't have a graphing calculator handy, you don't have this information. So let's pretend we don't know what the graph looks like, and try x=- 6 as our test zero: As you can see, the remainder is non-zero, so x=-6 is not a solution of 2x* + 72 16x + 6 = 0. But we need to notice something else: look at the signs on the numbers in the bottom row. We divided by a negative, and the signs on the bottom row alternate (plus, minus, plus, minus). +1,2,36,,3 -62 7 -16 6 -12 30 -84 2 -5 14 -78 The relationship is this: If you divide by a negative and end up with alternating signs on the bottom row, then the test root was too low. (This does not work in reverse! You can sometimes divide by a too-low test root, but not get alternating signs on the bottom row!) Now let's try a too-high test root. We'll try x=2 as the test zero: As you can see, the remainder is non-zero, so x=2 is not a solution of 2x* + 7x* 16x + 6 =0. But I'd like you to notice the bottom row again. I divided by a positive, The relationship is this: If you divide by a negative and end up with alternating signs on the bottom row, then the test root was too low. (This does not work in reverse! You can sometimes divide by a too-low test root, but not get alternating signs on the bottom row!) Now let's try a too-high test root. We'll try x=2 as the test zero: As you can see, the remainder is non-zero, so x=2 is not a solution of 2x* + 7x> 16x + 6 =0. But I'd like you to notice the bottom row again. I divided by a positive, and the signs on the bottom row are all positive. 212 7 -16 6 e 4 22 12 2 1 6 18 The relationship is this: If you divide by a positive and end up with all positive numbers on the bottom row, then the test root is too high. (This does not work in reverse! You can sometimes divide by a too-high test root, but not get all positive numbers on the bottom row!) In either case, "0" may be counted as positive or negative (though technically it is neither), according to whichever pattern you're trying to match. For instance, if you'd divided by a negative and your bottom row was "1 -3 2 0 4 -5", then you could count the "0" as being negative, so the signs are alternating, and your test root was too low. In similar manner, if you'd divided by a positive and your bottom row was "1 3 2 0 4 5", then you could count the "0" as being positive, so the signs are all positive, and your test root was too high. Note: These are the only two patterns. If you divide by a negative and get all positives, all negatives, or any pattern other than alternating signs, then the bottom row tells you nothing. You cannot conclude anything about whether or not the test root was too low (or too high). If you divide by a positive and get all negatives, alternating signs, or any pattern other than all positives, then the bottom row tells you nothing. You cannot conclude anything about whether or not the test root was too high (or too low). In practice, this means that generally the bottom row won't tell you much! Getting back to the problem at hand: We now know that x=-6 is too low. Wherever the zeroes are, they're above x=-6. So now we'll try x=-2: The bottom row does not have alternating signs, so we can't tell from this whether or not is too low (or too high). (From the picture, we know that it is neither it is actually between two zeroes, but we cannot tell this from the synthetic division.) However, ew can conclude something useful from this result. Since the remainder for the first division was -78, this meant that f{-6) =-78, by the Remainder Theorem. This last division says that f{-2) = 50. Since f(-6) is negative (that is, below the x-axis) and f{-2) is positive (that is, above the x-axis), then the graph must cross the x-axis somewhere between x=-6 and x=-2. That is, there must be a zero of f{x) =2x* + 72 - 16x + 6 between x=-6 and x=-2. The only rational candidate is x=-3, so we'll try that: Nope; whatever the zero is between x =6 and x=-2, it isn't rational. However, since f{-3) = 63, which is positive, then we have narrowed down the | irrational zero: it will be between x=-6 and x=-3. We still need to find a zero, so now we'll try x=1, since we know that x=2 is too high: While the bottom row is not all positive (so we cannot conclude that x=1 is too high), we can conclude that a zero must lie between x=1 and x=2, because f{1)=-1 is negative and f(2) =18 is positive. The only rational candidate is x =3/, so I'll try that: Nope; x=3/, isn't a zero either. So the zero between x=1 and x=2 must be the other irrational root from the Quadratic Formula, the pair to the irrational root between x=-6 and x=-3. The rational root must lie elsewhere. Since f{-2) =48 is positive and f{1)=-6 is negative (so there must be a zero between x=-2 and x=1), one of x="3/,,x=-1, x="1/, and x =1/, must be the rational zero. 212 7 -16 6 -4 -6 4 2 3 22 50 -3|2 7 -16 6 -6 -3 57 Note: Descartes' Rule of Signs says that there is one negative root and either two or zero positive roots. Since we have already determined that there is an irrational root between x=-6 and x=-3 (so the negative root has already been partially located), then any rational root must be positive. Therefore, I can ignore x = 3/, x=-1, and x="1/, as possible roots. Okay, now I'll try x="1/,: Aha! We've finally found the rational root! And dividing out x=1/, (that is, dividing out the factor x - !/, ) leaves us with a quadratic which we can solve: Then the zeroes are: 112 7 -16 6 g 1 4 -6 2 8 -12 0 22 +8x12=0 P+4x-6=0 (4)4J(-4)* - 41)-6) 21) _4f16+24 -4+440 - 2 T2 4+ =%'/10=2i/1_0 ~-5.16, 1.16 w1 _o4 fin 2 7 -16 6 4 - 6 2 8 2x2 + 8x - 12 = 0 x2 + 4x - 6=0 X = -(4)+ (-4)2-4(1)(-6) 2(1) -4+ V16+24 -4+140 2 2 -4+2V/10 -2+ 10 2 -5.16, 1.16 x = 4, - 2+ v10 These polynomial-solution problems are usually long and annoying like this. You can probably see how looking at a graph can be very useful! But if you don't have access to a graphing calculator, you can (eventually) get the correct answer. It would be recommended that you practice, so you can get a "feel" for how these work. Now, let's try one more example that requires us to find ALL solutions of a higher order polynomial equation. You should expect to get some complicated solutions (that is, solutions containing square roots or complex numbers, or both). You will find these zeroes by applying the Quadratic Formula for the final quadratic factor. First, we'll apply the Rational Roots Test-- Wait. Actually, the first thing we'll do is check to see if x = 1 or x=-1 is a root, because these are the simplest roots to test for. This isn't an "official" first step, but it can often be a timesaver, because you can just look at the powers and the numbers. When x= 1, the polynomial evaluates as 2 + 3 - 30-57 -2 + 24 = -60, so x = 1 isn't a root. But when x= -1, we get -2 + 3 + 30 - 57 + 2 + 24=0, so x=-1 is a root, and we can do the synthetic division with x= -1 right now. This leaves us with the smaller polynomial 2x4+x - 31x2 - 26x + 24. (Since we've divided out the factor x + 1, we've reduced the degree of the polynomial by 1 That's how we know this is a degree-four polynomial.) Now we'll apply the Rational Roots Test to get a list of values to look at: From experience, we've learned that most of these problems have their zeroes near the middle of the list, rather than at the extremes. This isn't all course, but it's usually better to stay away from the larger numbers. In this case, we won't start off by trying stuff like x = -24 or x = 12. Instead, we smaller values like x = 2. This is a fourth-degree polynomial, so it has, at most, four x-intercepts, and we can see all four of them on the graph. It looks like one of the zeroes is around -3.5, but that isn't on the list that the Rational Roots Test gave us, so this must be an irrational root. It also looks like there may be zeroes at -1.5 and at 0.5. But theNow, let's try one more example that requires us to find ALL solutions of a higher order polynomial equation. You should expect to get some complicated solutions (that is, solutions containing square roots or complex numbers, or both). You will find these zeroes by applying the Quadratic Formula for the final quadratic factor. First, we'll apply the Rational Roots Test-- Wait. Actually, the first thing we'll do is check to see if x=1 or x=-1 is a root, because these are the simplest roots to test for. This isn't an "official" first step, but it can often be a timesaver, because you can just look at the powers and the numbers. When x =1, the polynomial evaluates as 2+3-30-57-2+24=-60, so x=1 isn't a root. But when x=-1, we get -2+3+30-57+2+24=0, so x=-1 is a root, and we can do the synthetic division with x=-1 right now. This leaves us with the smaller polynomial 2x* + x> 31x% - 26x + 24. (Since we've divided out the factor x+ 1, we've reduced the degree of the polynomial by 1. That's how we know this is a degree-four polynomial.) Now we'll apply the Rational Roots Test to get a list of values to look at: From experience, we've learned that most of these problems have their zeroes near the middle of the list, rather than at the extremes. This isn't always true, of course, but it's usually better to stay away from the larger numbers. In this case, we won't start off by trying stuff like x =-24 or x = 12. Instead, we'll start out with smaller values like x=2. This is a fourth-degree polynomial, so it has, at most, four x-intercepts, and we can see all four of them on the graph. It looks like one of the zeroes is around -3.5, but that isn't on the list that the Rational Roots Test gave us, so this must be an irrational root. It also looks like there may be zeroes at -1.5 and at 0.5. But the clearest solution looks to be at x =4 and since whole numbers are easier to work with than fractions, x =4 would probably be a good value to try: The zero remainder says that x=4 is a root. This leaves us with 2x> + 9x> + 5x 6. Looking at the constant term "6", we can see now that x==+24,+12, +8, and -4 won't work as rational roots (even if we didn't already know from the graph), so I can cross them off of my list. (Always check the numbers as you go. The Rational Roots Test can give a very long list of possibilities, and it can be helpful to notice that some of those values can be ignored, especially if you don't have a graphing calculator to "cheat" with.) Comparing the remaining values on the list with the intercepts on the graph, I'll try x=1/2: The remainder isn't zero, so that test root didn't work. This means that the zero close to x=1/2 on the graph must be irrational; we'll find it when we apply the Quadratic Formula later. For now, I'll try x=-3/2: The division came out evenly, and this leaves us with the polynomial 2x> + 6x - 4. Since we're looking for the zeroes of the polynomial, what wereally have here is 2x? +6x - 4=0. Dividing through by 2 to get smaller numbers gives us x?+3x-2 =0, to which we can apply the Quadratic Formula: Then the complete solution is: o Find all the zeroes of the following polynomial: 2x +3x* - 30x> - 57x* 2x + 24 -112 3 =30 -57 -2 24 -2 -1 31 26 -24 2 1 =31 -26 24 0 i1,2,3,4,6,8,12,24 :il 12 2 412 1 -31 -26 24 ,1%,2,4,6,8,12,24 Then the complete solution is: o Find all the zeroes of the following polynomial: 2x5 + 3x* - 30x3 - 57x* - 2x + 24 -1]12 3 -30 =57 -2 24 -2 -1 31 26 -24 2 1 =31 -26 24 0 + 1234681224 1,3 54681224 12 22 412 1 -31 26 24 8 36 20 -24 29 5 -6 0 1 - L2 9 5 -6 15 5 2 10 10 -1 -3 -9 6 3+ Foa()(-2) - _ ((-2) -3+6+8 _ 3217 256 056 m = 2(1) 2 2 3+17 3 4 N S x=-1 s i 2 2 Note: Asking you to find the zeroes of a polynomial means the same thing as asking you to find the solutions to a polynomial equation. The zeroes are the values of x that make the polynomial equal zero. So the above problem could have been stated along the lines of "Find the solutions to 2x' + 3x* 30x> 57x2 - 2x + 24 =0" or "Find the solutions to 2x + 3x* - 30x> 57x% - 2x = 24", and the answers would have been the same. For problems 1-3, use the Rational Root Theorem to list all possible rational solutions. Then find the actual rational solutions. SHOW YOUR WORK. 1. x3 + x2 + 4x = -4 2. 2x3 - 9x2 - 1 1x + 8 =0 3. 2x4 - 5x3 - 17x2 + 41x - 21 = 0 For problems 4 and 5, list the possible number of positive and negative real roots using Descartes' Rule of Signs. SHOW YOUR WORK. 4. f(x) = 3x3+ 10x2 - x - 12 5. f(x) = x5 - 2x4- 3x3+ 6x2 - 4x +8 For problems 6 and 7, use synthetic division to determine the answer. SHOW YOUR WORK. 6. Which one of the binomials below is a factor of the polynomial x3 + 4x2 + x - 6? x + 4 x - 4 x+ 3 X - 3 x - 2 x + 17. Which one of the following numbers is a zero of the polynomial x3 + 3x - 4? .2 -1 O W H For problems 8-10, list ALL roots (rational, irrational, and/or complex) of the given polynomial equation by using the methods discussed in this lesson. SHOW YOUR WORK. Watch the 14-minute video in the lesson for steps required to show work. 8. x3 - 5x2 + 7x - 35 = 0 9. 4x3 + 16x2 - 22x - 10 = 0 10. 4x4 - 37x2 + 9 = 0

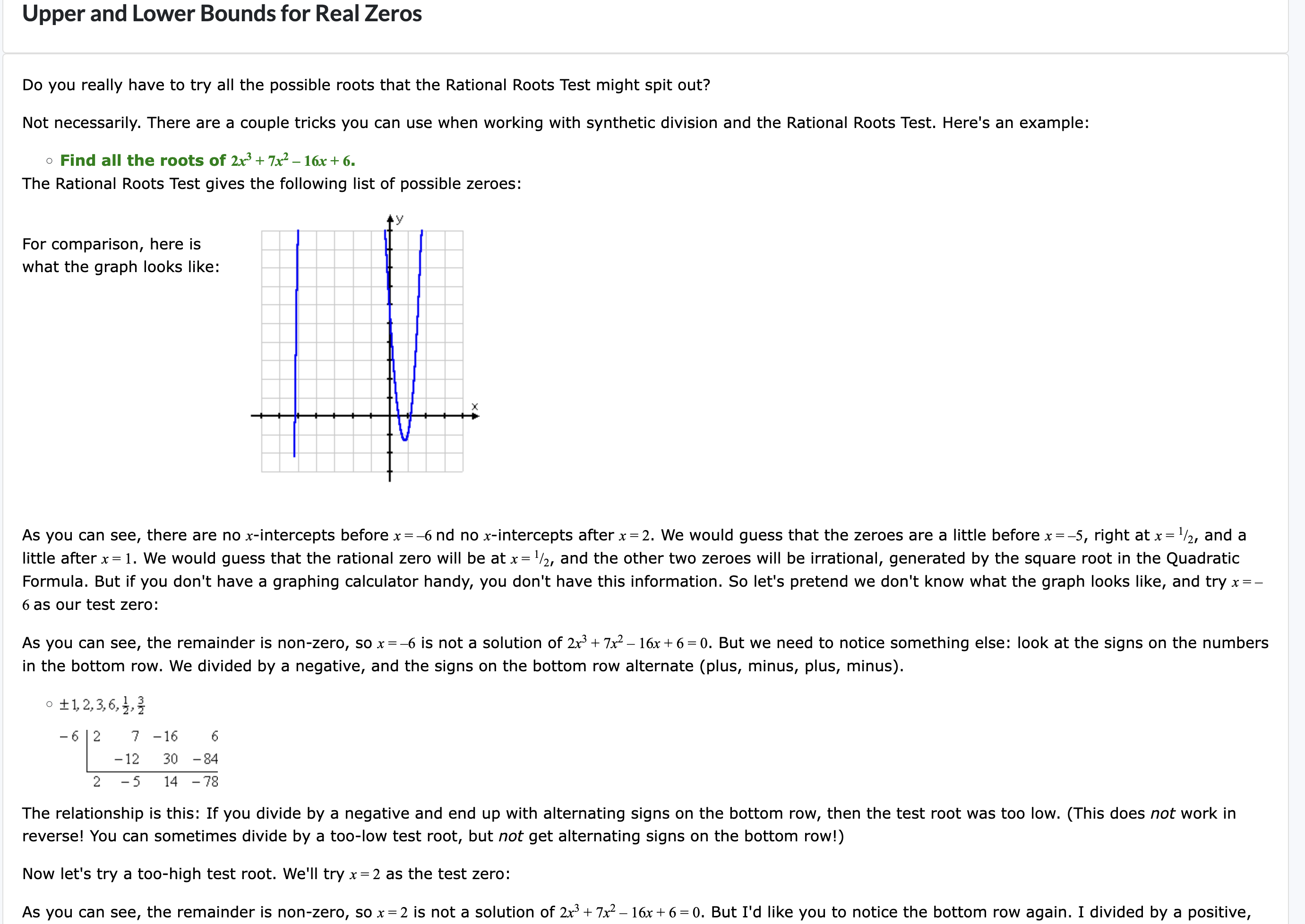

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts