Question: Lisa Benton (A) Case Study (OB, HR Management and Legal) In this project, we will be looking at a workplace scenario and individual behaviour while

Lisa Benton (A)

Case Study (OB, HR Management and Legal)

In this project, we will be looking at a workplace scenario and individual behaviour while analysing them using the concepts learnt.

Questions will be based on analysing the case and making decisions on behalf of the protagonist. (Case Study in below Images)

Lisa Benton (1) Case Study (OB, HR Management and Legal)

In this project, we will be looking at a workplace scenario and individual behaviour while analysing them using the concepts learnt.

Questions will be based on analysing the case and making decisions on behalf of the protagonist. (Case Study in below Images)

Question 1

Lisa felt disappointed during her first few weeks at Houseworld. What, according to you, caused friction between her and her team members: Linton and Scoville? Mention at least 2 instances? (4 marks)

Question 2 - Scoville displayed erratic behaviour while interacting with Lisa throughout the case.

Question 2A: Analyse Scovilles personality using the OCEAN framework. What, according to you, would he score in each of the OCEAN traits? Cite examples or instances to support your answer. (5 marks)

Note: You can mention either a 'high' or a 'low' for each of the 5 traits. Answer based on the information given in the case study.

Question 2B: Using the results of the OCEAN framework analysis, suggest two ways in which Lisa can improve her relationship with Scoville. (2 marks)

Question 3: Linton failed to recognise Lisas core strengths during Lisas performance evaluation. This left Lisa disappointed.

Question 3A: Which area of the Johari window does this situation represent? (1 mark)

Question 3B: What can Lisa do to reduce this area and improve her relationship with Linton? Give at least two relevant examples. (4 marks)

Question 3C: (4 marks) In Lisa's performance review, Linton described Lisa as "unassertive" and "lacking in initiative and confidence". What could Linton have done differently while giving the feedback? Suggest two improvements

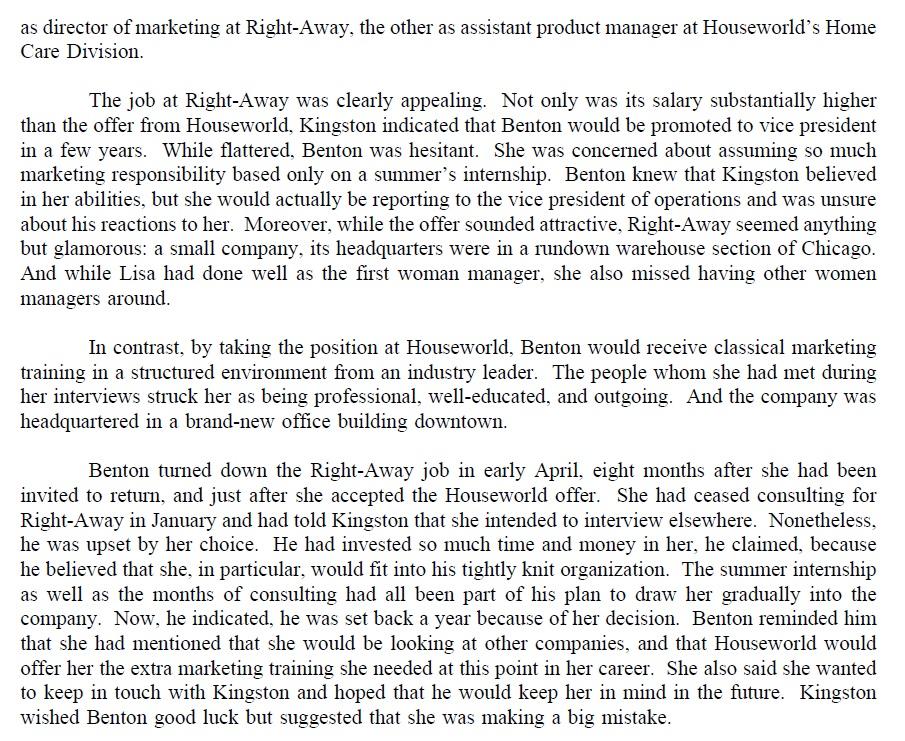

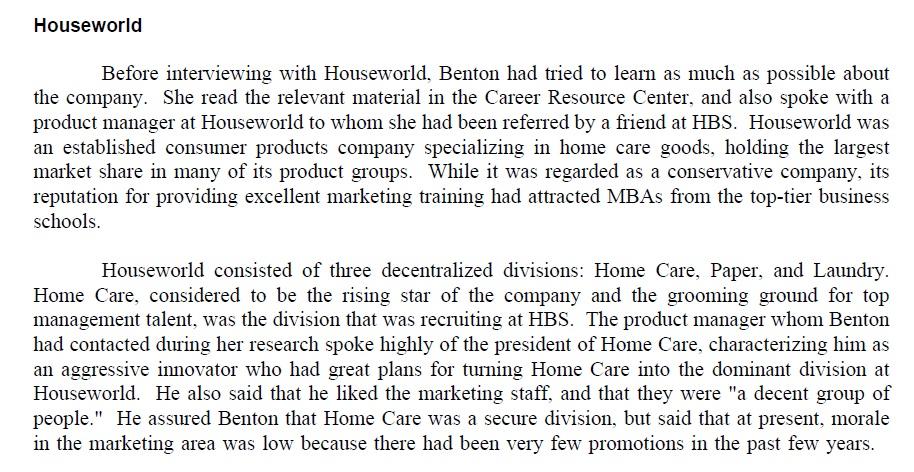

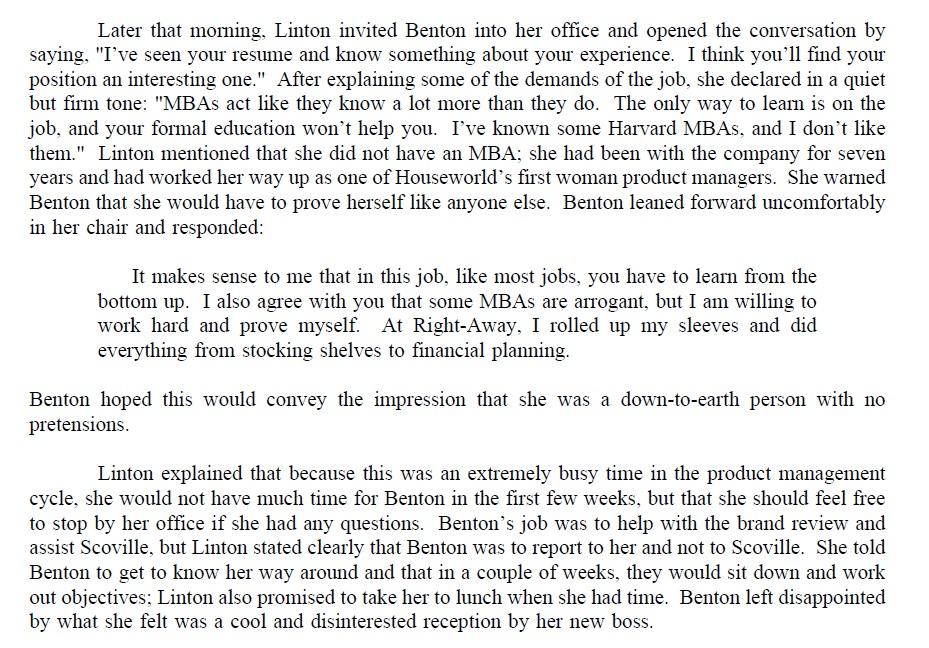

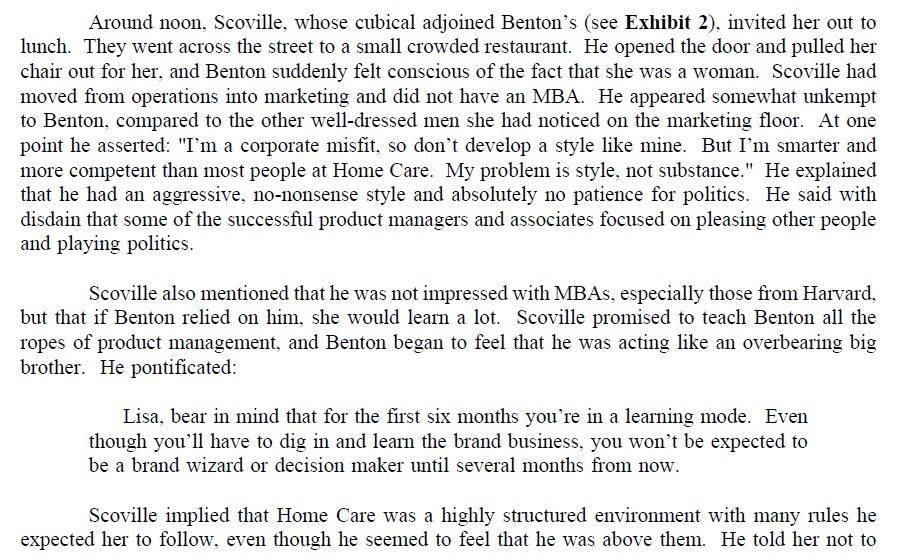

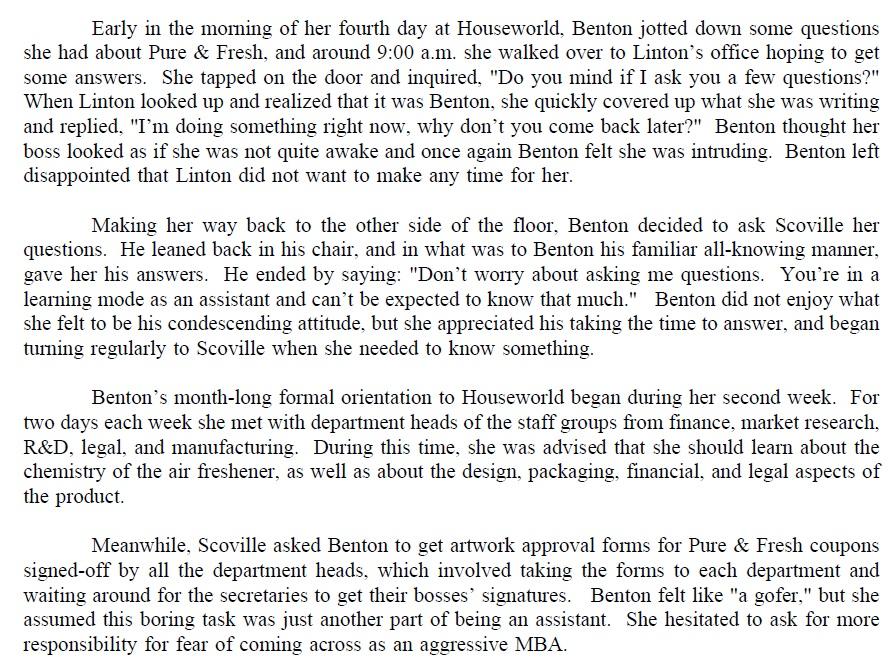

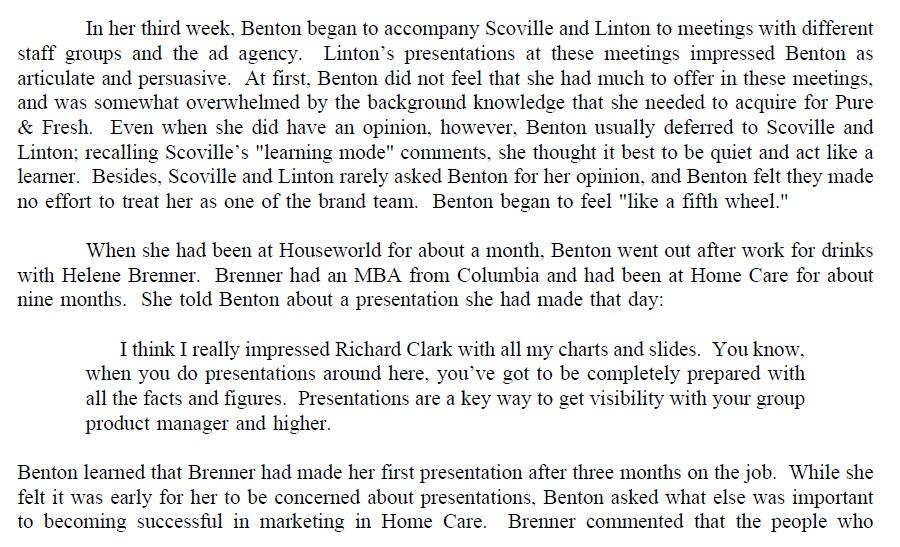

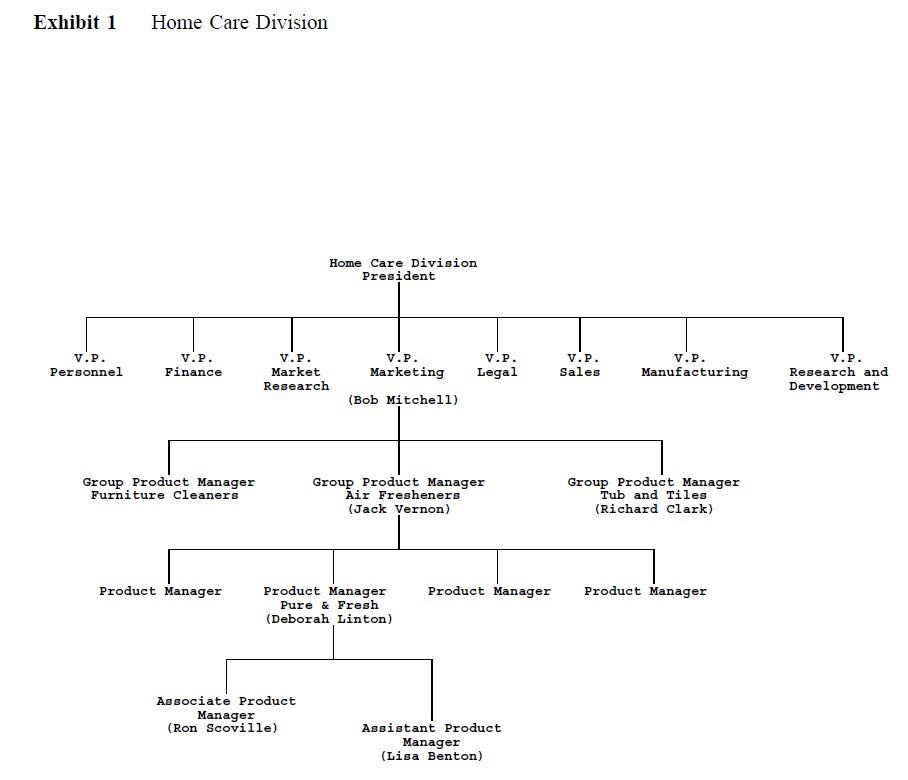

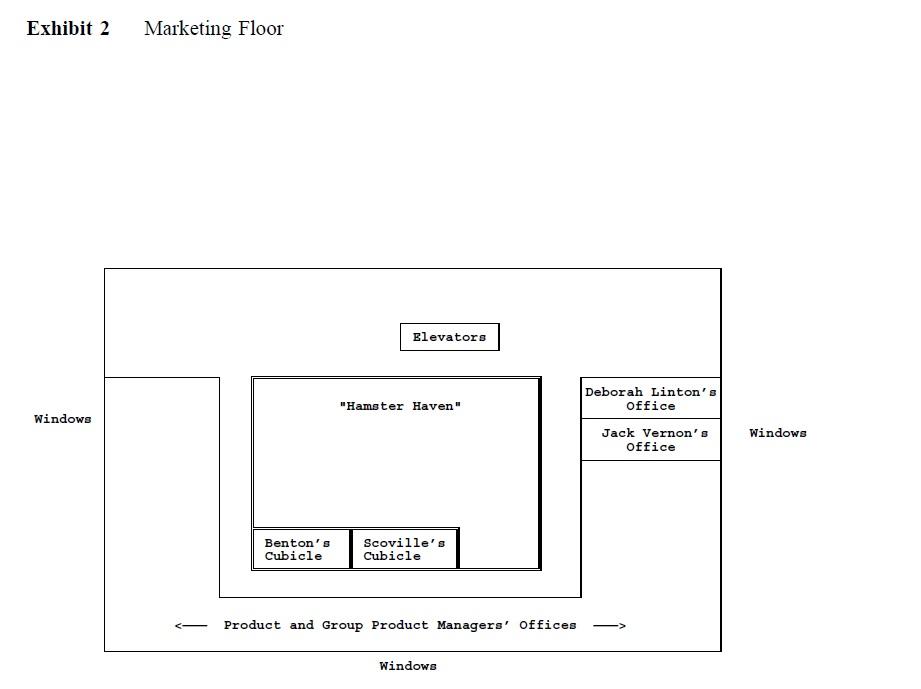

Lisa Benton (A) Early one afternoon in mid-October 1991, Lisa Benton, 27, gazed at the thin partitions of her cubicle and reflected on the past four months of her job as an assistant product manager in the Home Care Division of Houseworld. Benton was bored with her job and lack of responsibility and frustrated by her relationships with her boss, Deborah Linton, and her colleague, associate product manager Ron Scoville. From her first day at work, when Linton had informed her that she did not like Harvard MBAs, Benton had struggled unsuccessfully to please her boss. A series of stormy exchanges with Scoville had compounded her problems; recently he had accused her of being a "cocky MBA" when she expressed her opinion. Benton was concerned about these events, and especially about her less- than-promising performance review, and she contemplated her future in the company with increasing consternation. Background Between her first and second years at the Harvard Business School (HBS), Benton worked as assistant to the president of Right-Away Stores, a premier chain of convenience food stores based in Chicago. She enjoyed the job and was proud of the new nonmerchandising services that she had successfully introduced, in particular, the in-line roller skate ("rollerblades") rentals, a project she had supervised from concept to execution. The kickoff to this project, a skating cookout, had been a huge morale-booster for Right-Away employees. Right-Away president Scott Kingston, himself a Harvard MBA, was especially pleased with Benton's performance. Not only had she been the first woman manager in the company, her "roll-up-your-sleeves" approach won people over and allowed Benton to relate well to employees at all levels. At the end of the summer internship, Kingston offered her a full-time position upon graduation, as well as part-time consulting during her second year at HBS. Job Choice Benton and her husband finished their studies simultaneously and faced the decision of where they would go next. Chicago held opportunities for both of them, and Benton's husband would take up residency in a hospital in that city in July. Lisa Benton had to choose between two positions: one as director of marketing at Right-Away, the other as assistant product manager at Houseworld's Home Care Division The job at Right-Away was clearly appealing. Not only was its salary substantially higher than the offer from Houseworld, Kingston indicated that Benton would be promoted to vice president in a few years. While flattered, Benton was hesitant. She was concerned about assuming so much marketing responsibility based only on a summer's internship. Benton knew that Kingston believed in her abilities, but she would actually be reporting to the vice president of operations and was unsure about his reactions to her. Moreover, while the offer sounded attractive, Right-Away seemed anything but glamorous: a small company, its headquarters were in a rundown warehouse section of Chicago. And while Lisa had done well as the first woman manager, she also missed having other women managers around. In contrast, by taking the position at Houseworld, Benton would receive classical marketing training in a structured environment from an industry leader. The people whom she had met during her interviews struck her as being professional, well-educated, and outgoing. And the company was headquartered in a brand-new office building downtown. Benton turned down the Right-Away job in early April, eight months after she had been invited to return, and just after she accepted the Houseworld offer. She had ceased consulting for Right-Away in January and had told Kingston that she intended to interview elsewhere. Nonetheless, he was upset by her choice. He had invested so much time and money in her, he claimed, because he believed that she, in particular, would fit into his tightly knit organization. The summer internship as well as the months of consulting had all been part of his plan to draw her gradually into the company. Now, he indicated, he was set back a year because of her decision. Benton reminded him that she had mentioned that she would be looking at other companies, and that Houseworld would offer her the extra marketing training she needed at this point in her career. She also said she wanted to keep in touch with Kingston and hoped that he would keep her in mind in the future. Kingston wished Benton good luck but suggested that she was making a big mistake. Houseworld Before interviewing with Houseworld, Benton had tried to learn as much as possible about the company. She read the relevant material in the Career Resource Center, and also spoke with a product manager at Houseworld to whom she had been referred by a friend at HBS. Houseworld was an established consumer products company specializing in home care goods, holding the largest market share in many of its product groups. While it was regarded as a conservative company, its reputation for providing excellent marketing training had attracted MBAs from the top-tier business schools. Houseworld consisted of three decentralized divisions: Home Care, Paper, and Laundry. Home Care, considered to be the rising star of the company and the grooming ground for top management talent, was the division that was recruiting at HBS. The product manager whom Benton had contacted during her research spoke highly of the president of Home Care, characterizing him as an aggressive innovator who had great plans for turning Home Care into the dominant division at Houseworld. He also said that he liked the marketing staff, and that they were "a decent group of people." He assured Benton that Home Care was a secure division, but said that at present, morale in the marketing area was low because there had been very few promotions in the past few years. When Benton interviewed at Home Care, she met with several product managers, and was particularly impressed with Group Product Manager Richard Clark (Exhibit 1). Benton also talked more informally at lunch and dinner with some of the assistant and associate product managers. One, a Wharton MBA, told Benton that the product management staff was a supportive bunch who worked hard but liked to have fun. The 8:30 to 5:30 hours that most marketing people kept seemed very reasonable to Benton, and she planned to lead a balanced life. Benton asked what her role would be as a new assistant product manager, and they told her she would assume responsibility quickly and become a product manager within two to three years. Benton knew from researching the other top consumer packaging companies that the route to product management usually took from three to four years, and she was attracted by Home Care's faster career path. In the first year she would be immersed in the day-to-day brand business through assignments on different product management teams. Benton learned that product managers generally moved assignments every 18 to 24 months and associates and assistant product managers moved assignments every 12 to 18 months. This practice, typical of the leading brand management companies, allowed product managers to acquire experience in different stages of the product life cycle; it sometimes made it difficult, however, to develop close working relationships. Benton also learned that Houseworld used an MBO evaluation process (conducted annually in January using very specific objectives) and that promotion occurred from within. It was the product manager's responsibility to groom his or her associates to be "promotable." At the end of the lunch, one of the associate product managers told her, "You're the kind of person the company wants. You're so enthusiastic." Benton was offered the job of assistant product manager in the Home Care Division, and was invited to return to the company for a second visit. As was standard procedure at Home Care and other consumer packaging companies, she was informed that she would not know until the first day of work who her boss was, or to what product she had been assigned. Because working relationships had always been important to her, this prospect made Benton somewhat nervous, but it was reassuring to know that she had liked all of the people she had met at Houseworld. They seemed warm and down-to-earth, and Benton thought she would be able to get along with most of them. On April 7, Benton accepted the job at Home Care. Initiation Arriving at 8:30 a.m. on June 15 for her first day at Houseworld, Benton was taken to meet her new boss, Deborah Linton, a woman that Benton had not met during the interview process. Benton was immediately struck by Linton's attractive office on the twentieth floor and her boss's sophisticated appearance and confident manner. Linton greeted Benton pleasantly, and said that she was not expecting Benton for another week and that her office was not set up yet. She then called in Ron Scoville, the associate product manager, and asked him to help Benton get settled. Assistant and associate product managers worked in cubicles situated in the middle of the twentieth floor. Dividers five-and-a-half feet tall separating the small, rectangular offices had given the area the nickname "Hamster Haven" (Exhibit 2). While gathering supplies to stock her new office, Benton noticed Richard Clark, the group product manager who had impressed her during the recruiting process. She was disappointed that he barely remembered her, and did not stop to welcome her aboard. Later that morning. Linton invited Benton into her office and opened the conversation by saying, "I've seen your resume and know something about your experience. I think you'll find your position an interesting one." After explaining some of the demands of the job, she declared in a quiet but firm tone: "MBAs act like they know a lot more than they do. The only way to leam is on the job, and your formal education won't help you. I've known some Harvard MBAs, and I don't like them." Linton mentioned that she did not have an MBA; she had been with the company for seven years and had worked her way up as one of Houseworld's first woman product managers. She warned Benton that she would have to prove herself like anyone else. Benton leaned forward uncomfortably in her chair and responded: It makes sense to me that in this job, like most jobs, you have to learn from the bottom up. I also agree with you that some MBAs are arrogant, but I am willing to work hard and prove myself. At Right-Away, I rolled up my sleeves and did everything from stocking shelves to financial planning. Benton hoped this would convey the impression that she was a down-to-earth person with no pretensions. Linton explained that because this was an extremely busy time in the product management cycle, she would not have much time for Benton in the first few weeks, but that she should feel free to stop by her office if she had any questions. Benton's job was to help with the brand review and assist Scoville, but Linton stated clearly that Benton was to report to her and not to Scoville. She told Benton to get to know her way around and that in a couple of weeks, they would sit down and work out objectives; Linton also promised to take her to lunch when she had time. Benton left disappointed by what she felt was a cool and disinterested reception by her new boss. Around noon, Scoville, whose cubical adjoined Benton's (see Exhibit 2), invited her out to lunch. They went across the street to a small crowded restaurant. He opened the door and pulled her chair out for her, and Benton suddenly felt conscious of the fact that she was a woman. Scoville had moved from operations into marketing and did not have an MBA. He appeared somewhat unkempt to Benton, compared to the other well-dressed men she had noticed on the marketing floor. At one point he asserted: "I'm a corporate misfit, so don't develop a style like mine. But I'm smarter and more competent than most people at Home Care. My problem is style, not substance." He explained that he had an aggressive, no-nonsense style and absolutely no patience for politics. He said with disdain that some of the successful product managers and associates focused on pleasing other people and playing politics. Scoville also mentioned that he was not impressed with MBAs, especially those from Harvard, but that if Benton relied on him, she would learn a lot. Scoville promised to teach Benton all the ropes of product management, and Benton began to feel that he was acting like an overbearing big brother. He pontificated: Lisa, bear in mind that for the first six months you're in a learning mode. Even though you'll have to dig in and learn the brand business, you won't be expected to be a brand wizard or decision maker until several months from now. Scoville implied that Home Care was a highly structured environment with many rules he expected her to follow, even though he seemed to feel that he was above them. He told her not to be late for meetings, and not to rely on the train, the means of transportation she said she was planning to use, because sometimes she would need to stay late. After lunch, Benton returned to her new office and started reading product literature on Pure & Fresh, the solid air freshener brand that Linton had assigned her that morning. One of the assistant product managers Benton had dined with during recruiting stopped by her cubicle and gave Benton a warm, enthusiastic welcome; she grimaced, however, upon learning about Benton's brand assignment with Scoville and Linton. Around four o'clock, Benton asked Scoville what she could do to help on the brand review, and he handed her a large stack of reports to copy. Benton completed the task around 7:00 p.m.; most of the other product management staff had left around 5:30 p.m. As she reviewed her first day at Houseworld on her way home. Benton felt ambivalent. She was excited about working in an environment where people seemed intelligent and sophisticated, but she was disappointed in her brand assignment. Pure & Fresh seemed like such an unnecessary consumer product; she would have preferred a furniture cleaning product because she loved fine furniture and cared about its maintenance. Yet promoting a successful new brand could be exciting, and top management would be likely to pay close attention to its progress. While she was disturbed by Linton's cool welcome and bothered by Scoville's condescending manner, her first impressions had been wrong before, and she would give them the benefit of the doubt. First Two Months The next morning, Benton read more company and product literature, and at 10:00 a.m. she walked over to Linton's office to see if there was anything she could do. Scoville was sitting very close to Linton discussing some aspect of the brand review. Benton thought they seemed somewhat intimate, and she felt like an intruder. Linton suggested that Benton keep reading and getting to know her way around the company, and that she would meet with her to tell her about Pure & Fresh's history in about an hour. In that meeting, Benton learned that Linton had been in her present job eight months and that Benton was the first assistant product manager assigned to the brand. At noontime, Helene Brenner, one of the assistant product managers Benton had met during interviewing, invited Benton to join her and some other product management staffers for lunch in the company cafeteria, where, according to Brenner, "everyone" ate. In the group Benton and Brenner joined, everyone was from a different brand. They were all very friendly and asked Benton questions about her background and personal life; they seemed to Benton more interested in her than Scoville and Linton had been. Benton listened to a discussion about MBAs in product management and learned that under the direction of the vice president of marketing, Bob Mitchell, a Harvard MBA (see Exhibit 1), recruiting practices had been changed. Previously, new assistant product managers were selected from a mix of MBA and non-MBA candidates; the emphasis now was on recruiting MBAs from top-notch schools for entry-level marketing positions. As a result, the Home Care Division was becoming increasingly dominated by people holding MBAs. Benton thought this helped explain Scoville and Linton's apparent resentment of her. Two associate product managers at Benton's table complained about the lack of upward mobility in Home Care beyond their level. One warned Benton that if anyone ever asked her what her goals were, she should reply that she wanted to "get ahead" at Houseworld, and never say "I'm at Houseworld to get some good marketing training." Early in the morning of her fourth day at Houseworld, Benton jotted down some questions she had about Pure & Fresh, and around 9:00 a.m. she walked over to Linton's office hoping to get some answers. She tapped on the door and inquired, "Do you mind if I ask you a few questions?" When Linton looked up and realized that it was Benton, she quickly covered up what she was writing and replied, "I'm doing something right now, why don't you come back later?" Benton thought her boss looked as if she was not quite awake and once again Benton felt she was intruding. Benton left disappointed that Linton did not want to make any time for her. Making her way back to the other side of the floor, Benton decided to ask Scoville her questions. He leaned back in his chair, and in what was to Benton his familiar all-knowing manner, gave her his answers. He ended by saying: "Don't worry about asking me questions. You're in a learning mode as an assistant and can't be expected to know that much." Benton did not enjoy what she felt to be his condescending attitude, but she appreciated his taking the time to answer, and began tuining regularly to Scoville when she needed to know something. Benton's month-long formal orientation to Houseworld began during her second week. For two days each week she met with department heads of the staff groups from finance, market research, R&D, legal, and manufacturing. During this time, she was advised that she should learn about the chemistry of the air freshener, as well as about the design, packaging, financial, and legal aspects of the product. Meanwhile, Scoville asked Benton to get artwork approval forms for Pure & Fresh coupons signed-off by all the department heads, which involved taking the forms to each department and waiting around for the secretaries to get their bosses signatures. Benton felt like "a gofer," but she assumed this boring task was just another part of being an assistant. She hesitated to ask for more responsibility for fear of coming across as an aggressive MBA. In her third week, Benton began to accompany Scoville and Linton to meetings with different staff groups and the ad agency. Linton's presentations at these meetings impressed Benton as articulate and persuasive. At first, Benton did not feel that she had much to offer in these meetings, and was somewhat overwhelmed by the background knowledge that she needed to acquire for Pure & Fresh. Even when she did have an opinion, however, Benton usually deferred to Scoville and Linton; recalling Scoville's "learning mode" comments, she thought it best to be quiet and act like a learner. Besides, Scoville and Linton rarely asked Benton for her opinion, and Benton felt they made no effort to treat her as one of the brand team. Benton began to feel "like a fifth wheel." When she had been at Houseworld for about a month, Benton went out after work for drinks with Helene Brenner. Brenner had an MBA from Columbia and had been at Home Care for about nine months. She told Benton about a presentation she had made that day: I think I really impressed Richard Clark with all my charts and slides. You know, when you do presentations around here, you've got to be completely prepared with all the facts and figures. Presentations are a key way to get visibility with your group product manager and higher. Benton learned that Brenner had made her first presentation after three months on the job. While she felt it was early for her to be concerned about presentations, Benton asked what else was important to becoming successful in marketing in Home Care. Brenner commented that the people who succeeded were "enthusiastic, but not pushy, and were ambitious, creative, and analytical." Brenner cautioned Benton about working long hours: Don't stay at the office after 6:00. You don't get points around here for working late. I heard about an assistant product manager who didn't get promoted because he was really disorganized and was always at the office until at least 7:00. In Benton's fifth week, Linton asked her to analyze some sales data and to write a memo on her findings. Benton knew memos were important at Houseworld, and that writing good ones was a key to receiving top management visibility. Linton had Benton revise her memo four times before she passed it up to the group product manager, Jack Vernon. The memo was well-received, and Vernon personally commended Benton on her work with a scrawl at the top of the memo saying "Nice job." Even so, Benton derived little sense of accomplishment because she had not been allowed to make recommendations or take any action beyond the analysis. Instead, Scoville and Linton used the analysis to develop plans for Pure & Fresh television ads, which looked much more exciting than her assignments. From what she had been told in the reciuiting process, and given her responsibilities and accomplishments at Right-Away, Benton expected to be more involved in all aspects of the brand business, and after developing action plans every day for two years at HBS, she was dissatisfied with only performing analyses. Several days later, Benton spoke with Gary Carter, an associate product manager with whom she shared her train commute and chatted regularly. His brand group also had a new assistant who had just started, and Benton learned that she was "helping plan a promotion for next year, and working on pricing recommendations." Benton described the assignments that she had been given, and revealed that she felt frustrated and underutilized. She did not mention, however, the difficulties she was having with Linton and Scoville, since she believed that "loyalty to one's superiors was essential in the corporate world." Carter agreed that Benton's abilities were not being fully used, but had no explanation for her situation. Benton was discouraged, and wondered if she was doing something wrong or if she had gotten stuck with a lousy management team. Benton thought that except for Linton and Scoville, she was getting along well with the people in her network at Home Care, and had made it a point to be friendly to everyone. Her peers frequently invited her to go to lunch and for drinks after work. Benton often chatted with the brand's secretary, and had no problems getting her work typed on time; when she needed people from the staff groups to provide her with information, she always got their cooperation. She was confident that Jack Vernon liked her, based on his commendations on her memos and from chats the two had about Harvard On the other hand, her relationships with Linton and Scoville had not appreciably advanced. Scoville frequently called over the divider: "Lisa, can you run these numbers for me?" and "Lisa, when will all the approvals be signed?" Unlike Benton, Scoville often had trouble getting others to do his bidding, and frequently ended up doing such tasks himself or asking Benton to do them. Six weeks had passed and Linton still had not given Benton her objectives, as she had promised on the first day, nor had she invited her to lunch. An assistant product manager's first year with Houseworld was supposedly critical for later success, and Benton began to have some doubts about her future with the company, especially as she recalled a few incidents that had occurred in her third and fourth months. The Typing Incident One afternoon in August, Benton was trying to complete a memo and she noticed that the headings on one of her charts, which had been created by the staff secretary, were not lined up properly. Since error-free reports were expected in Home Care, she decided it must be corrected. The secretary was now on vacation. Benton knew the other secretaries were extremely pressed for time while the brand review was being formalized, so she sat down at a computer for five minutes and redid the chart herself. As she returned to her cubicle, she noticed Vernon walking in her direction, and she was surprised and disturbed by his insistence that she come to his office immediately. Once inside his office, Vernon quickly shut the door, leaned back in his chair, and said to Benton: I don't know what you were doing, but I never want to see you doing word processing in this company again. We have secretaries to do that kind of work and there is no reason why you, particularly a woman, should be seen doing it. It destroys your credibility not only with the people on your team, but also in the secretaries' eyes. Benton, slightly annoyed, responded: You really misinterpreted the situation. I was only there for a few minutes and thought it would be much quicker to fix the heading on one of my charts myself than to wait until one of the other secretaries had some time to make the correction. We really don't have adequate coverage with our secretary on vacation. She thanked Vernon for his concern, and said that it would not happen again; but inside, she felt angry. She regarded her work as part of a team effort and considered his reaction overblown. But she also wondered if Vernon might have a point and recognized that he was looking out for her interests. Linton's office was next to Vernon's, and she had observed Benton going into his office. Later that day, she asked Benton about the incident and became furious at her description. "He had no right to tell you that," she said when she heard the story. "First of all, he should have told me and let me talk to you, and secondly, that whole issue itself is ridiculous." Benton suspected that her boss was fuming because Vernon had gone over her head and approached Benton directly. Several days later, Linton mentioned that she had discussed the matter with Vernon and commented: "You know, there are times and places when we have to do things like word processing." While Benton still was not sure what she should do in future situations, she concluded that since Vernon was more senior in the department, she would follow his instructions. The Copying Episode A week after the typing incident, Benton was working on a coupon test market booklet that would be mailed to 600,000 homes in three test cities. Benton's job was to help design the Pure & Fresh coupons and iron out the details with the company producing the booklets. Linton and Scoville were rushing to meet their own deadlines on the marketing plan. At one point, Scoville called to Benton from his cubicle. Tired of his patronizing manner and his demands, she retorted, "I'll be there in a minute." Five minutes later, she walked into his office. Scoville wanted Benton to do some copying for him while he made some last-minute corrections on the marketing plan. She replied that she would do the copying with him in a while, but she was occupied with her own project for the moment. When he insisted that she do it immediately, she snapped: "Ron, why don't you plan your time better and do your own copying?" "Oh, I see, you're too good for copying," he responded. Furious, Benton snatched up the papers and headed for the copy machine. When Benton returned from lunch that day, she found a note on her desk summoning her to Linton's office. "I understand you're too good for copying." Linton said when Benton entered. For the first time feeling genuine animosity toward her boss, Benton proclaimed: That is patently false. Half of the material is already on Ron's desk and I'm going to finish the rest this afternoon. I was upset because he treated me like some servant girl, and I was getting tired of his patronizing attitude. I have never felt too good for this kind of work. In fact, when I was at Right-Away last summer, I counted inventory. I dusted the shelves, I... Linton cut her off, shouting: This is a team effort. Everyone is overworked. You'll just have to contribute. Copying is a part of your job, even if you are a Harvard MBA. Benton felt there was no point in arguing with her. Abruptly rising, she snapped, "I'm going to do the rest of the copying right now." Benton felt furious and frustrated. It was the first time that a boss had actually yelled at her. She felt that Linton should have acted as a buffer between her and Scoville, and instead she blamed Benton. Marching into Scoville's office, Benton announced: You had a lot of gall going to Deborah when I've been doing a lot of tasks for you. I don't mind copying, and I've never felt "too good" for copying, but I expect you to ask me for favors without being so condescending. Scoville apologized: "I'm sorry this happened. I had no idea that I came across so brusquely, or that you would be so sensitive. I'll try to work on my behavior next time." Benton felt stuck: if she performed clerical tasks, she would be criticized by Vernon; if she did not comply with Scoville's requests, she would be attacked for not being a team player. On the train ride home that evening she mentioned the incident to her friend Gary Carter, and asked his advice on how to deal with Scoville. Carter was surprised; Benton had rarely talked about Scoville with Carter because she knew that the two got along. While she was beginning to feel freer talking with trusted friends about Scoville, loyalty to her boss still seemed important to Benton, and she played down Linton's role in the incident. Carter suggested that Benton should stand up to Scoville and "not take his crap." "Easier said than done," she thought to herself. Five days later, Vernon unexpectedly called Benton into his office. He seemed concerned to Benton, and asked, "Lisa, are you happy here?" The question surprised her, and Benton guessed that her unhappiness must have showed in her demeanor, since normally people described her as "bubbly and enthusiastic" and she knew that she had not been so recently. "I'm OK," she replied, "I have my ups and downs like everyone else." Vernon did not seem satisfied. "Are you sure there isn't something that you want to talk about, like how things are going with Deborah and Ron?" Vernon seemed genuinely concerned, but Benton felt she should be cautious. "I'm having some problems with Ron, but Deborah has been really good about helping me." Vernon agreed that Scoville's style was difficult to deal with, and Benton thanked him for his interest. Benton thought she had been smart politically by expressing loyalty to her boss and making her look good in her superior's eyes. However, she still was unsure how to manage her relationships with Scoville and Linton. Performance Evaluation Two weeks later, Benton went out for dinner with Carol Patlin, another assistant product manager with whom she had become friends. Patlin had been with Houseworld for four years and had moved from finance into marketing, and she knew a lot about company practices and office rumors. She asked Benton if she had received her performance review yet, explaining that it was customary to have one after three months on the job. During the evening, she also told Benton that Linton and Scoville were rumored to be having an affair. On September 15, Benton approached Linton saying, "I've been here for three and understand it's customary to have a review after that time period. I want to know if I'm meeting your expectations, and how to work on plans for my development." Linton responded: "If you really want one, I'll sit down with you in a few days and give you a performance review." Again, Benton felt that she was imposing on Linton's time. A week later, Linton took Benton out to lunch in a nearby hotel restaurant and immediately withdrew a small folded piece of paper from her briefcase. She told Benton that she had jotted down some notes about her performance, and that she wanted to keep the discussion informal. Linton began by listing Benton's strengths. She commended her on her ability to get along with the staff groups and the marketing department, for learning quickly how the company "worked," and for her written communication skills. She said that Benton was doing a "nice job," but that there were several areas in which she needed to improve. She then outlined Benton's weaknesses: not taking initiative in structuring projects for herself, a lack of assertiveness in making her opinions known, and being too quiet in meetings with Scoville and the staff groups. She said that she thought Benton was intelligent, but that she "lacked confidence." Benton asked for examples of behavior needing improvement, and Linton replied: "When we are in meetings with the ad agency, you barely contribute your opinions. You always qualify your recommendations with, I'm not really familiar with ...?" Benton listened and nodded, and tried not to get defensive, but on the inside she felt disappointed and misunderstood. She explained that she had just been trying to act like a "learner." Since she knew that Linton had a close relationship with him, Benton hesitated to say anything negative about Scoville. She cautiously mentioned that Scoville often acted "patronizing" with her, and that it was difficult to be forceful and assertive around him since she felt he was overbearing. Linton agreed that Scoville's management style left a lot to be desired, but she believed that Benton should be able to get along with him. She pointed out that she never had any problems with Scoville herself. Benton agreed to work on the areas identified by her boss and asked Linton to define some responsibilities for her that would be separate from Scoville's. Linton agreed. After the lunch, Benton was acutely upset that her superior had failed to recognize some of her major strengths: analytical skills, intellectual capacity, and organizational abilities. She was disturbed by Linton's feedback that she was "unassertive" and "lacking in initiative." Benton believed that Linton's criticisms accurately described her behavior at Houseworld, but they were inconsistent with what Benton felt her "true self" to be. On the one hand, Benton felt that Linton had not given her the opportunity to demonstrate her usually assertive personality; on the other hand, Benton blamed herself for not being true to her own character. Benton also felt that she had faced conflicting messages from the very beginning: she was warned not to act like an arrogant MBA, and she was faulted for not being assertive enough. Realizing that her future at the company might be in jeopardy, Benton vowed to "act more like herself," but was still doubtful about what kinds of projects she could initiate. Another Run-in with Scoville Ten days after her lunch with Linton, Benton was deeply embroiled in an analysis of Pure & Fresh pricing. She stepped into Scoville's office to show him her analysis and recommendations. He seemed impressed, and Benton, pleased, returned to her desk to complete the profit calculations. A few minutes later, however, Scoville appeared and asked her how she had arrived at her figures. When Benton displayed her spreadsheet, Scoville began challenging her assumptions. Frustrated with his attitude. Benton muttered: "That's ridiculous!" Then Scoville yelled in a voice audible across the entire floor: You arrogant MBAs are all alike. You think you know everything. You're so cocky. When you've been around for a while, you'll see that your analysis is wrong! Deciding not to come down to his level by yelling back, Benton retorted that she was trying to express her point of view. Fuming, she finally pronounced: "Oh, forget it and just get out of here." Benton was furious, and she also felt embarrassed and humiliated. "I hate it here," she thought. "I want to leave. I don't need to put up with this." Another associate, a woman that Benton was not particularly fond of, saw Benton's distraught face and suggested that they go to the conference room to talk. Benton, who until now had volunteered very little about her problems with Scoville and Linton, spilled out her frustrations: "I'm so sick of trying to get along with that creep! He is so condescending and makes me feel like an idiot. Nothing I've tried works with him." Benton's colleague agreed and remarked that many of the other product management staff members felt similarly about Scoville. She advised Benton to ignore him and "just get through your time with him." She then asked Benton whether Linton had helped in any way. "She's told us to work things out ourselves," Benton replied. "I think she has just been copping out." After this conversation, Benton returned to her desk only to be called into Linton's office a few hours later. Word of the confrontation had gotten around, Linton informed Benton, and several people had complained about Scoville's "destructive" behavior and his "condescending" treatment of Benton. Linton said once more that she could not understand Benton's problems with Scoville: "Ron is one of my best friends. I know others don't like him, but I think he is misunderstood and that he has a heart of gold." Linton promised again that she would try to assign them discrete projects, but insisted that they try to get along with each other. Benton nodded her head, but believed that Linton would do nothing to make the relationship any better. On her way back to her desk, Benton considered the fact that getting along with Scoville was probably essential to her success on the brand. While Scoville's style was abhorrent, Benton felt he was indeed open to feedback, and there had been occasions when he had come across as a decent, even warm, person. Benton returned to Scoville's cubicle and suggested that they meet after work. Over drinks, Scoville apologized for hurting Benton's feelings, and talked about his frustration with the organization and the fact that he had not been promoted yet. They agreed that they would try to cooperate. Soul-searching While Scoville and Benton managed to avoid confrontation after that, Benton still felt overshadowed. After the yelling incident, several of the other associates and assistants in Hamster Haven rallied to Benton's support. The general advice she received was to "hang in there"; and they reminded her that Pure & Fresh was only a temporary assignment. Benton's peers agreed that Scoville "couldn't get along with anyone," and they viewed Linton as an "excellent performer with a great track record of brand successes," but a "poor trainer and manager of people." An assistant product manager who had worked for Linton the previous year told Benton that Linton had done a "terrible job" training him. He said he was now "working doubletime" trying to make up for what he should have learned in his first position. This new information was disconcerting to Benton. Benton appreciated the camaraderie and support from her peers, but her concerns about her future with Houseworld were not alleviated. She still felt that her talents and training were not being fully utilized. Benton continued to be troubled by what she considered Linton's "lack of interest" in her development; it seemed clear to Benton that her mind was preoccupied with other matters. Concerned that her slow start at Houseworld would negatively affect her prospects for promotion, she considered approaching Vernon to ask him to switch her to another brand. But as far as Benton knew, no assistant product manager had ever done this at Houseworld; she was reluctant to alienate not only her superiors, but possibly her peers as well, by making such an unusual request. Benton was also tempted to call Scott Kingston, the president of Right-Away Stores, to inform him that she had made a mistake in turning down his attractive offer. Although Kingston had been angry at Benton's rejection of his offer, Benton thought that if she was absolutely serious about leaving Houseworld, she could call him; a former Right-Away colleague had told Benton that Kingston still spoke highly of Benton's contribution to the organization. Exhibit 1 Home Care Division Home Care Division President V.P. Personnel V.P. Finance V.P. Market Research V.P. Marketing (Bob Mitchell) V.P. Legal V.P. Sales V.P. Manufacturing V.P. Research and Development Group Product Manager Furniture Cleaners Group Product Manager Air Fresheners (Jack Vernon) Group Product Manager Tub and Tiles (Richard Clark) Product Manager Product Manager Product Manager Product Manager Pure & Fresh (Deborah Linton) Associate Product Manager (Ron Scoville) Assistant Product Manager (Lisa Benton) Exhibit 2 Marketing Floor Elevators "Hamster Haven" Windows Deborah Linton's Office Jack Vernon's office Windows Benton's Cubicle Scoville's Cubicle Product and Group Product Managers' Offices Windows

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts