Question: many wealthy people continue working long hard hours sometimes beyond retirement age read below for ideas about reason for motivational pattern is the acquisition of

many wealthy people continue working long hard hours sometimes beyond retirement age read below for ideas about reason for motivational pattern is the acquisition of wealth still a motivator for these individuals (1 to 2 pages)

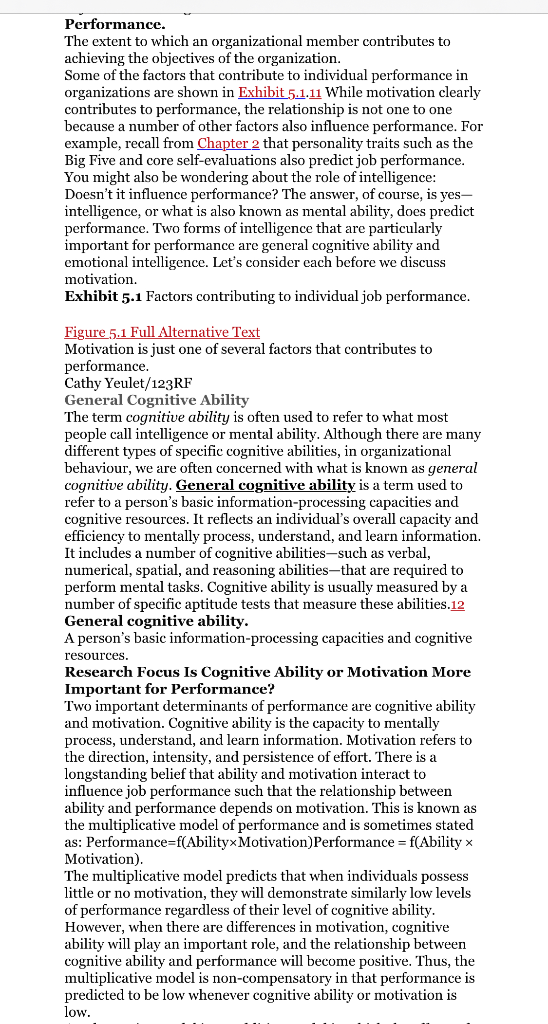

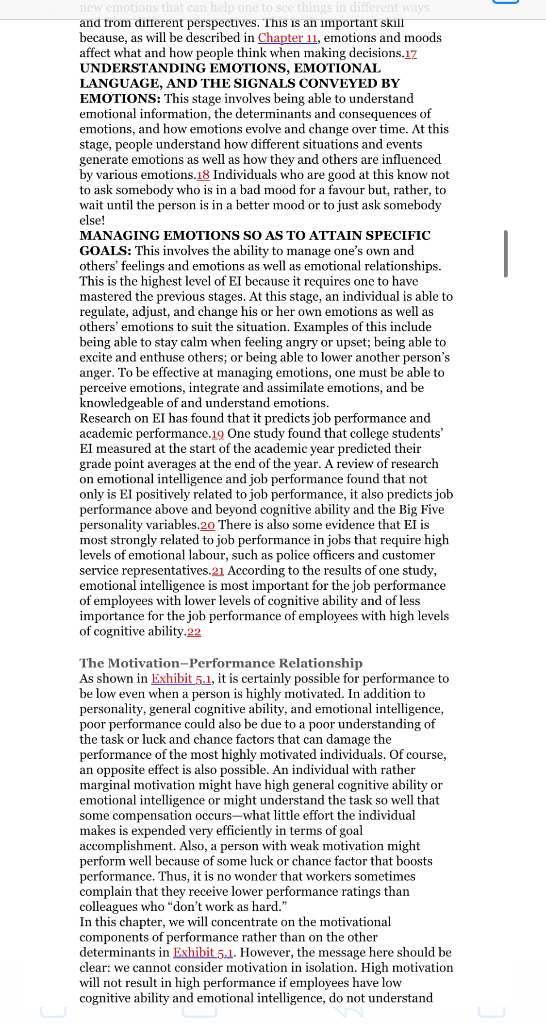

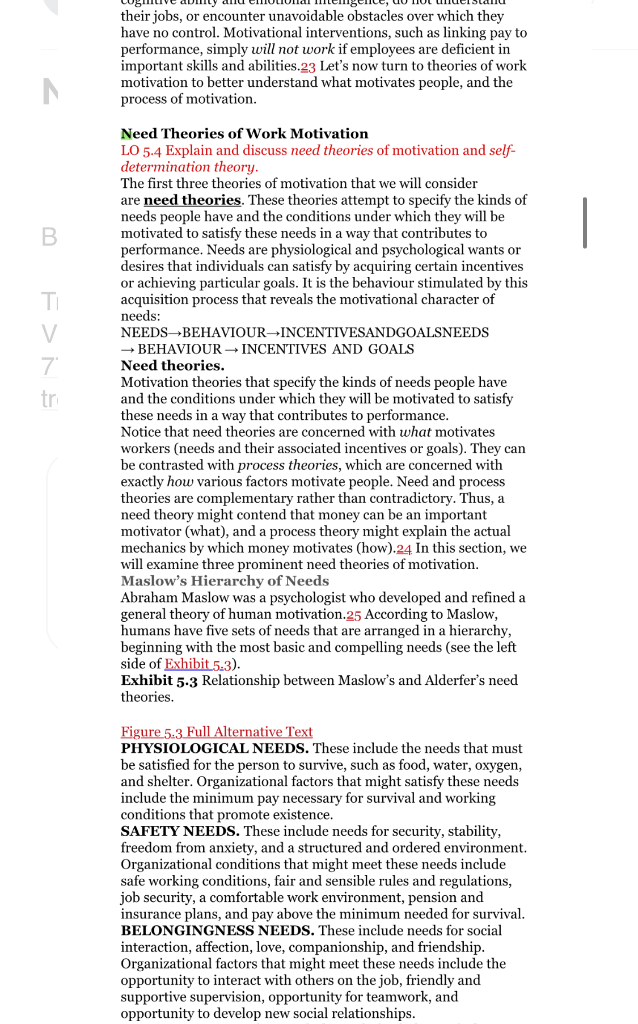

predict Chapter 5 Theories of Work Motivation Learning Objectives AFTER READING CHAPTER 5, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO: 5.1 Define motivation, discuss its basic properties, and distinguish it from performance. 5.2 Compare and contrast intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. 5.3Explain and discuss the different factors that performance, and define general cognitive ability and emotional intelligence. 5.4Explain and discuss need theories of motivation and self- determination theory. 5.5Explain and discuss the process theories of motivation. 5.6Discuss the cross-cultural limitations of theories of motivation. 5.7Summarize the relationships among the various theories of motivation, performance, and job satisfaction. DevFacto Technologies Inc. Mike McKinnon had a lot going on. In fact, that's an understatement. With a newborn at home, the developer was still spending long hours at Edmonton IT consultancy DevFacto Technologies Inc. He was working on a big project that had run into some snags, and the pressure was on. If the job was successful, the company would bankroll a trip for all its employees to Las Vegas. Instead of grumbling, the sleep- deprived McKinnon doubled his efforts to make sure the job was done right. And when he and his wife finally did board the plane to Las Vegas, his company gave them a pair of o catch a show as a further thank you. DevFacto Technologies of Edmonton, Alberta, was founded by Chris Izquierdo and David Cronin in 2007. Both had previously worked as software developers in rigidly bureaucratic firms and decided to start their own IT consulting practice. Their dream was to create a different kind of organization with a healthy workplace that allowed talent to flourish, while building superior software that had a brilliant customer-service edge. They focused on a simple equation: happyemployees=happycustomershappy employees = h appy customers. In starting their own company, the thinking was that a self- motivated workforce would make for a less hierarchical, more efficient, and more productive business. "If you get a bunch of driven people who are intrinsically motivated to do good work, you shouldn't have to monitor them using managers," says Cronin. "If you give them a purpose that's larger than themselves, you can lead them to results." DevFacto has more than doubled in size since 2010 and now has offices in Calgary, Regina, and Toronto. Job applicants go through a lengthy culture-fit interview with Cronin or a regional director. I'm looking for evidence of intrinsic motivation, that thing that's driving them to be better," says Cronin. Employees also participate in group interviews to assess candidates and have the power to veto a hire who won't fit in. De Facto employees are responsible for keeping one another accountable to deadlines, budgets, and other concerns. "People do need some pressure and attention put on them," Cronin says. "That can come from a boss walking around, or it can come from peers giving you feedback and challenging you," says Cronin. He feels the latter approach is a more potent way to make people understand their own role in the overall health of the organization. Motivation at DevFacto is more than just intrinsic. For example, new hires receive three weeks of vacation per year to start. The company offers all employees $2500 per year for any vocational training (including photography classes, cooking classes, public speaking classes, and self-help books), $100 per month for travel expenses (including a bus pass), and free beer on Fridays from the company's beer fridge. Employees also receive an annual $1200 cellphone and home-internet subsidy. The company also has a profit-sharing program that they use every year to implement two new benefit programs for its employees. For example, in 2011, the company introduced a $500-per-year wellness fund that can be used for anything from a gym membership to a tablet computer, and a 52-cent-per-kilometre subsidy whenever an employee has to travel for work. In 2012, the company introduced a $1000-per-year vacation subsidy to encourage employees to use their minimum three weeks of vacation per year. The second program in 2012 was a plan to match a percentage of each employee's RRSP Motivated employees are the key to the success of DevFacto Technologies Inc., which has been named one of the Best Workplaces in Canada and the best place for millennials to work in Alberta. Dev Facto Technologies The company also hosts DevFacto Development Days four times a year. Employees are split into teams and have free rein to create whatever they want, be it a technical process or a mobile application. At the end of the day, their creations are showcased to the rest of the DevFacto team. Today, DevFacto is an award-winning company with 120 consultants across Canada. DevFacto has been named one of the Best Workplaces in Canada, Best Small and Medium Employers in Canada, and the best place for millennials to work in Alberta. It has also been recognized as one of Canada's fastest growing companies. Its average annual employee retention rate is 97 percent. Cronin believes that, by investing in their young employees, "they will return the favour by working hard and being loyal."1 Would you be motivated if you worked for DevFacto Technologies? What kind of person would respond well to the company's motivational techniques? What underlying philosophy of motivation is being used, and what effect does it have on employees' motivation and performance? These are some of the questions that this chapter will explore. First, we will define motivation and distinguish it from performance. After that, we will describe several popular theories of work motivation and contrast them. Then, we will explore whether these theories translate across cultures. Finally, we will present a model that links motivation, performance, and job satisfaction. Why Study Motivation? Motivation is one of the most traditional topics in organizational behaviour, and it has interested managers, researchers, teachers, and sports coaches for years. However, a good case can be made that motivation has become even more important in contemporary organizations. Much of this is a result of the need for increased productivity for organizations to be globally competitive. It is also a result of the rapid changes that contemporary organizations are undergoing. Stable systems of rules, , regulations, and procedures that once guided behaviour are being replaced by requirements for flexibility and attention to customers that necessitate higher levels of initiative. This initiative depends on motivation. Perhaps it is not surprising that motivation has been described as the number one problem facing many organizations today. What would a good motivation theory look like? In fact, as we shall see, there is no single, all-purpose motivation theory. Rather, we will consider several theories that serve somewhat different purposes. In combination, though, a good set of theories should recognize human diversity and consider that the same conditions will not motivate everyone. Also, a good set of theories should be able to explain how it is that some people like those who work at DevFacto Technologies seem to be self-motivated, while others seem to require external motivation. Finally, a good set of theories should recognize the social aspect of human beings-people's motivation is often affected by how they see others being treated. Before getting to our theories, let's first define motivation more precisely What Is Motivation? LO 5.1 Define motivation, discuss its basic properties, and distinguish it from performance. The term motivation is not easy to define. However, from an organization's perspective, when we speak of a person as being motivated, we usually mean that the person works hard," "keeps at" his or her work, and directs his or her behaviour toward appropriate outcomes. Basic Characteristics of Motivation We can formally define motivation as the extent to which persistent effort is directed toward a goal.3 Motivation. The extent to which persistent effort is directed toward a goal. Effort The first aspect of motivation is the strength of the person's work- related behaviour, or the amount of effort the person exhibits on the job. Clearly, this involves different kinds of activities on different kinds of jobs. A loading-dock worker might exhibit greater effort by carrying heavier crates, while a researcher might reveal greater effort by searching out an article in some obscure foreign technical journal. Both are exerting effort in a manner appropriate to their jobs. Persistence The second characteristic of motivation is the persistence that individuals exhibit in applying effort to their work tasks. The organization would not be likely to think of the loading-dock worker who stacks the heaviest crates for two hours and then goofs off for six hours as especially highly motivated. Similarly, the researcher who makes an important discovery early in her career and then rests on her laurels for five years would not be considered especially highly motivated. In each case, workers have not been persistent in the application of their effort. Timoti Direction Effort and persistence refer mainly to the quantity of work an individual produces. Of equal importance is the quality of a person's work. Thus, the third characteristic of motivation is the direction of the person's work-related behaviour. In other words, do workers channel persistent effort in a direction that benefits the organization? Employers expect motivated stockbrokers to advise their clients of good investment opportunities and motivated software designers to design software, not play computer games. These correct decisions increase the probability that persistent effort is actually translated into accepted organizational outcomes. Thus, motivation means working smart as well as working hard. Goals Ultimately, all motivated behaviour has some goal or objective toward which it is directed. We have presented the preceding discussion from an organizational perspective-that is, we assume that motivated people act to enhance organizational objectives. In this case, employee goals might include high productivity, good attendance, or creative decisions. Of course, employees can also be motivated by goals that are contrary to the objectives of the organization, including absenteeism, sabotage, and embezzlement. In these cases, they are channelling their persistent efforts in directions that are dysfunctional for the organization. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation LO 5.2 Compare and contrast intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Some hold the view that people are motivated by factors in the external environment (such as supervision or pay), while others believe that people can, in some sense, be self-motivated without the application of these external factors. You might have experienced this distinction. As a worker, you might recall tasks that you enthusiastically performed simply for the sake of doing them and others that you performed only to keep your job or placate your boss. Experts in organizational behaviour distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. At the outset, we should emphasize that there is only weak consensus concerning the exact definitions of these concepts and even weaker agreement about whether we should label specific motivators as intrinsic or extrinsic. However, the following definitions and examples seem to capture the distinction fairly well. Intrinsic motivation stems from the direct relationship between the worker and the task and is usually self-applied. Feelings of achievement, accomplishment, challenge, and competence derived from performing one's job are examples of intrinsic motivators, as is sheer interest in the job itself. Off the job, avid participation in sports and hobbies is often intrinsically motivated. As described in the chapter-opening vignette, De Facto Technologies emphasizes intrinsic motivation even when hiring employees. Intrinsic motivation. Motivation that stems from the direct relationship between the worker and the task; it is usually self-applied. Extrinsic motivation stems from the work environment external to the task and is usually applied by someone other than the person being motivated. Pay, fringe benefits, company policies, and various forms of supervision are examples of extrinsic motivators. At DevFacto Technologies, the trip to Las Vegas and the vacation subsidy are examples of extrinsic motivators. Extrinsic motivation. Motivation that stems from the work environment external to the task; it is usually applied by others. Obviously, employers cannot package all conceivable motivators as neatly as these definitions suggest. For example, a promotion or a compliment might be applied by the boss but might also be a clear signal of achievement and competence. Thus, some motivators have both extrinsic and intrinsic qualities. The relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic motivators has been the subject of a great deal of debate. Some research studies have reached the conclusion that the availability of extrinsic motivators can reduce the intrinsic motivation stemming from the task itself.6 The notion is that when extrinsic rewards depend on performance, then the motivating potential of intrinsic rewards decreases. Proponents of this view have suggested that making extrinsic rewards contingent on performance makes individuals feel less competent and less in control of their own behaviour. That is, they come to believe that their performance is controlled by the environment and that they perform well only because of the reward.7 As a result, their intrinsic motivation suffers. However, a review of research in this area reached the conclusion that the negative effect of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation occurs only under very limited conditions and they are easily avoidable. Another review found that intrinsic motivation is a moderate to strong predictor of performance even when extrinsic rewards are present.8 As well, in organizational settings in which individuals see extrinsic rewards as symbols of success and as signals of what to do to achieve future rewards, they increase their task performance.9 Thus both intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation are related to performance. However, extrinsic motivation is more strongly related to the quantity of performance, while intrinsic motivation is more strongly related to the quality of performance. Furthermore, intrinsic motivation seems to be especially beneficial for performance on complex tasks, while extrinsic motivation is most beneficial for performance on more mundane tasks. 10 Thus, it is safe to assume that both kinds of rewards are important and compatible in enhancing work motivation and performance. Further, as you will see later in the chapter, many theories of work motivation make the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Motivation and Performance LO 5.3 Explain and discuss the different factors that predict performance, and define general cognitive ability and emotional intelligence. At this point, you may well be saying, ait a nute. I kno many people who are 'highly motivated' but just don't seem to perform well. They work long and hard, but they just don't measure up." This is certainly a sensible observation, and it points to the important distinction between motivation and performance. Performance can be defined as the extent to which an organizational member contributes to achieving the objectives of the organization. Ponfoumanan Performance. The extent to which an organizational member contributes to achieving the objectives of the organization. Some of the factors that contribute to individual performance in organizations are shown in Exhibit 5.1.11 While motivation clearly contributes to performance, the relationship is not one to one because a number of other factors also influence performance. For example, recall from Chapter 2 that personality traits such as the Big Five and core self-evaluations also predict job performance. You might also be wondering about the role of intelligence: Doesn't it influence performance? The answer, of course, is yes- intelligence, or what is also known as mental ability, does predict performance. Two forms of intelligence that are particularly important for performance are general cognitive ability and emotional intelligence. Let's consider cach before we discuss motivation. Exhibit 5.1 Factors contributing to individual job performance. Figure 5.1 Full Alternative Text Motivation is just one of several factors that contributes to performance. Cathy Yeulet/123RF General Cognitive Ability The term cognitive ability is often used to refer to what most people call intelligence or mental ability. Although there are many different types of specific cognitive abilities, in organizational behaviour, we are often concerned with what is known as general cognitive ability. General cognitive ability is a term used to refer to a person's basic information-processing capacities and cognitive resources. It reflects an individual's overall capacity and efficiency to mentally process, understand, and learn information. It includes a number of cognitive abilities such as verbal, numerical, spatial, and reasoning abilities-that are required to perform mental tasks. Cognitive ability is usually measured by a number of specific aptitude tests that measure these abilities.12 General cognitive ability. A person's basic information-processing capacities and cognitive resources. Research Focus Is Cognitive Ability or Motivation More Important for Performance? Two important determinants of performance are cognitive ability and motivation. Cognitive ability is the capacity to mentally process, understand, and learn information. Motivation refers to the direction, intensity, and persistence of effort. There is a longstanding belief that ability and motivation interact to influence job performance such that the relationship between ability and performance depends on motivation. This is known as the multiplicative model of performance and is sometimes stated as: Performance=f(Abilityx Motivation Performance = f(Ability Motivation) The multiplicative model predicts that when individuals possess little or no motivation, they will demonstrate similarly low levels of performance regardless of their level of cognitive ability: However, when there are differences in motivation, cognitive ability will play an important role, and the relationship between cognitive ability and performance will become positive. Thus, the multiplicative model is non-compensatory in that performance is predicted to be low whenever cognitive ability or motivation is low. An alternative model is an additive model in which the effects of cognitive ability and motivation on performance are independent and compensatory. Thus, according to the additive model, individuals' level of motivation does not affect the relationship between cognitive ability and performance. Thus, individuals who possess a low level of motivation could compensate for this to some extent with a higher level of cognitive ability. Although the idea of a multiplicative model is widely accepted and can be found in several theories of motivation and models of job performance, there have been few actual tests of it, and not all studies have found support for it. Therefore, to learn more about the relationship between cognitive ability and motivation for performance, Van Iddekinge, Aguinis, Mackey, and DeOrtentiis conducted a comprehensive test of the multiplicative model using data from studies that measured cognitive ability, motivation, and performance. The authors conducted an extensive literature search that resulted in 55 independent studies. The results indicate that cognitive ability and motivation are both important for performance. With respect to the correlations with performance, both cognitive ability and motivation were positively correlated. As for the multiplicative model, there was very little support. Rather, performance was mostly predicted by the additive effects of cognitive ability and motivation. In terms of the relative importance of cognitive ability and motivation, the results indicate that they contribute equally to the prediction of job performance. However, cognitive ability was a much stronger predictor of training performance and performance on work- related tasks in laboratory studies. Cognitive ability was also a stronger predictor of objective measures of performance whereas cognitive ability and motivation contribute equally to the prediction of subjective measures of performance. In summary, the results of this study do not support the multiplicative model of performance. Rather, the results suggest that when it comes to predicting performance, what matters most are the additive or independent effects of cognitive ability and motivation. In other words, the effects of cognitive ability and motivation on performance are additive rather than multiplicative. Furthermore, cognitive ability and motivation appear to be equal when predicting job performance. Thus, motivation is just as important as cognitive ability when it comes to job performance. Source: Based on Van Iddekinge, C. H., Aguinis, H., Mackey, J. D., & DeOrtentiis, P. S. (2018). A meta-analysis of the interactive, additive, and relative effects of cognitive ability and motivation on performance. Journal of Management, 44, 249-279. Research has found that general cognitive ability predicts learning, training, career success, and job performance in all kinds of jobs and occupations, including those that involve both manual and mental tasks. This should not be surprising, because many cognitive skills are required to perform most jobs. General cognitive ability is an even better predictor of performance for more complex and higher level jobs that require the use of more cognitive skills and involve more information processing.13 Thus, both general cognitive ability and motivation are necessary for performance. This raises an interesting question: What is more important for performance, cognitive ability or motivation? To find out, see Research Focus: Is Cognitive Ability or Motivation More Important for Performance? Emotional Intelligence Emotional Intelligence Although the importance of general cognitive ability for job performance has been known for many years, researchers have only recently begun to study emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence (EI) has to do with an individual's ability to understand and manage his or her own and others' feelings and emotions. It involves the ability to perceive and express emotion, assimilate emotion in thought, understand and reason about emotions, and manage emotions in oneself and others. Individuals high in El are able to identify and understand the meanings of emotions and to manage and regulate their emotions as a basis for problem solving, reasoning, thinking, and action.14. Emotional intelligence. The ability to understand and manage one's own and others' feelings and emotions. Peter Salovey and John Mayer, who are credited with first coining the term emotional intelligence, have developed an El model that consists of four interrelated sets of skills, or branches. The four skills represent sequential steps that form a hierarchy. The perception of emotion is at the bottom of the hierarchy, followed by (in ascending order) using emotions to facilitate thinking, understanding emotions, and managing and regulating emotions. The four-branch model of EI is shown in Exhibit 5.2 and described here.15 Exhibit 5.2 Four-branch model of emotional intelligence. Source: Based on Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (2000). Emotional Intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27, 267298; Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition & Personality, 9, 185-211. Figure 5.2 Full Alternative Text PERCEIVING EMOTIONS ACCURATELY IN ONESELF AND OTHERS: This involves the ability to perceive emotions and to accurately identify one's own emotions and the emotions of others. An example of this is the ability to accurately identify emotions in people's faces and in non-verbal behaviour. People differ in the extent to which they can accurately identify emotions in others, particularly from facial expressions.16 This step is the most basic level of EI and is necessary to be able to perform the other steps in the model. USING EMOTIONS TO FACILITATE THINKING: This refers to the ability to use and assimilate emotions and emotional experiences to guide and facilitate one's thinking and reasoning. This means that one is able to use emotions in functional ways, such as making decisions and other cognitive processes (e.g., creativity, integrative thinking, and inductive reasoning). This stage also involves being able to shift one's emotions and generate new emotions that can help one to see things in different ways and from different perspectives. This is an important skill because, as will be described in Chapter 11, emotions and moods affect what and how people think when making decisions.17 TIONS EMOTIONAT UNDERSTANDING and from different perspectives. This is an important skill because, as will be described in Chapter 11, emotions and moods affect what and how people think when making decisions.17 UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS, EMOTIONAL LANGUAGE, AND THE SIGNALS CONVEYED BY EMOTIONS: This stage involves being able to understand emotional information, the determinants and consequences of emotions, and how emotions evolve and change over time. At this stage, people understand how different situations and events generate emotions well as how they and others are influenced by various emotions.18 Individuals who are good at this know not to ask somebody who is in a bad mood for a favour but, rather, to wait until the person is in a better mood or to just ask somebody else! MANAGING EMOTIONS SO AS TO ATTAIN SPECIFIC GOALS: This involves the ability to manage one's own and others' feelings and emotions as well as emotional relationships. This is the highest level of El because it requires one to have mastered the previous stages. At this stage, an individual is able to regulate, adjust, and change his or her own emotions as well as others' emotions to suit the situation. Examples of this include being able to stay calm when feeling angry or upset; being able to excite and enthuse others; or being able to lower another person's anger. To be effective at managing emotions, one must be able to perceive emotions, integrate and assimilate emotions, and be knowledgeable of and understand emotions. Research on El has found that it predicts job performance and academic performance.19 One study found that college students' El measured at the start of the academic year predicted their grade point averages at the end of the year. A review of research on emotional intelligence and job performance found that not only is El positively related to job performance, it also predicts job performance above and beyond cognitive ability and the Big Five personality variables.20 There is also some evidence that EI is most strongly related to job performance in jobs that require high levels of emotional labour, such as police officers and customer service representatives.21 According to the results of one study, emotional intelligence is most important for the job performance of employees with lower levels of cognitive ability and of less importance for the job performance of employees with high levels of cognitive ability.22 The Motivation-Performance Relationship As shown in Exhibit 5.1, it is certainly possible for performance to be low even when a person is highly motivated. In addition to personality, general cognitive ability, and emotional intelligence, poor performance could also be due to a poor understanding of the task or luck and chance factors that can damage the performance of the most highly motivated individuals. Of course, an opposite effect is also possible. An individual with rather marginal motivation might have high general cognitive ability or emotional intelligence or might understand the task so well that some compensation occurs-what little effort the individual makes is expended very efficiently in terms of goal accomplishment. Also, a person with weak motivation might perform well because of some luck or chance factor that boosts performance. Thus, it is no wonder that workers sometimes complain that they receive lower performance ratings than colleagues who don't work as hard." In this chapter, we will concentrate on the motivational components of performance rather than on the other determinants in Exhibit.5.1. However, the message here should be clear: we cannot consider motivation in isolation. High motivation will not result in high performance if employees have low cognitive ability and emotional intelligence, do not understand their jobs, or encounter unavoidable obstacles over which they have no control. Motivational interventions, such as linking pay to performance, simply will not work if employees are deficient in important skills and abilities.23 Let's now turn to theories of work motivation to better understand what motivates people, and the process of motivation. B. T V 7 tr Need Theories of Work Motivation LO 5.4 Explain and discuss need theories of motivation and self- determination theory. The first three theories of motivation that we will consider are need theories. These theories attempt to specify the kinds of needs people have and the conditions under which they will be motivated to satisfy these needs in a way that contributes to performance. Needs are physiological and psychological wants or desires that individuals can satisfy by acquiring certain incentives or achieving particular goals. It is the behaviour stimulated by this acquisition process that reveals the motivational character of needs: NEEDS BEHAVIOUR INCENTIVESANDGOALSNEEDS BEHAVIOUR INCENTIVES AND GOALS Need theories. Motivation theories that specify the kinds of needs people have and the conditions under which they will be motivated to satisfy these needs in a way that contributes to performance. Notice that need theories are concerned with what motivates workers (needs and their associated incentives or goals). They can be contrasted with process theories, which are concerned with exactly how various factors motivate people. Need and process theories are complementary rather than contradictory. Thus, a need theory might contend that money can be an important motivator (what), and a process theory might explain the actual mechanics by which money motivates (how).24 In this section, we will examine three prominent need theories of motivation. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Abraham Maslow was a psychologist who developed and refined a general theory of human motivation.25 According to Maslow, humans have five sets of needs that are arranged in a hierarchy, beginning with the most basic and compelling needs (see the left side of Exhibit.5.3). Exhibit 5.3 Relationship between Maslow's and Alderfer's need theories. Figure 5.3 Full Alternative Text PHYSIOLOGICAL NEEDS. These include the needs that must be satisfied for the person to survive, such as food, water, oxygen, and shelter. Organizational factors that might satisfy these needs include the minimum pay necessary for survival and working conditions that promote existence. SAFETY NEEDS. These include needs for security, stability, freedom from anxiety, and a structured and ordered environment. Organizational conditions that might meet these needs include safe working conditions, fair and sensible rules and regulations, job security, a comfortable work environment, pension and insurance plans, and pay above the minimum needed for survival. BELONGINGNESS NEEDS. These include needs for social interaction, affection, love, companionship, and friendship. Organizational factors that might meet these needs include the opportunity to interact with others on the job, friendly and supportive supervision, opportunity for teamwork, and opportunity to develop new social relationships. ESTEEM NEEDS. These include needs for feelings of adequacy, competence, independence, strength, and confidence, and the appreciation and recognition of these characteristics by others. Organizational factors that might satisfy these needs include the opportunity to master tasks leading to feelings of achievement and responsibility. Also, awards, promotions, prestigious job titles, professional recognition, and the like might satisfy these needs when they are felt to be truly deserved. SELF-ACTUALIZATION NEEDS. These needs are the most difficult to define. They involve the desire to develop one's true potential as an individual to the fullest extent and to express one's skills, talents, and emotions in a manner that is most personally fulfilling. Maslow suggests that self-actualizing people have clear perceptions of reality; accept themselves and others; and are independent, creative, and appreciative of the world around them. Organizational conditions that might provide self-actualization include absorbing jobs with the potential for creativity and growth as well as a relaxation of structure to permit self-development and personal progression. Given the fact that individuals may have these needs, in what sense do they form the basis of a theory of motivation? That is, what exactly is the motivational premise of Maslow's hierarchy of needs? Put simply, the lowest-level unsatisfied need category has the greatest motivating potential. Thus, none of the needs is a "best" motivator; motivation depends on the person's position the need hierarchy. According to Maslow, individuals are motivated to satisfy their physiological needs before they reveal an interest in safety needs, and safety must be satisfied before social needs become motivational, and so on. When a need is unsatisfied, it exerts a powerful effect on the individual's thinking and behaviour, and this is the sense in which needs are motivational. However, when needs at a particular level of the hierarchy are satisfied, the individual turns his or her attention to the next higher level. Notice the clear implication here that a satisfied need is no longer an effective motivator. Once one has adequate physiological resources and feels safe and secure, one does not seek more of the factors that met these needs but looks elsewhere for gratification. According to Maslow, the single exception to this rule involves self-actualization needs. He felt that these are "growth" needs that become stronger as they are gratified. Maslow's hierarchy of needs. A five-level hierarchical need theory of motivation that specifies that the lowest-level unsatisfied need has the greatest motivating potential. Alderfer's ERG Theory Clayton Alderfer developed another need-based theory, called ERG theory.26 It streamlines Maslow's need classifications and makes some different assumptions about the relationship between needs and motivation. The name ERG stems from Alderfer's compression of Maslow's five-category need system into three categories: existence, relatedness, and growth needs. EXISTENCE NEEDS. These are needs that are satisfied by some material substance or condition. As such, they correspond closely to Maslow's physiological needs and to those safety needs that are satisfied by material conditions rather than interpersonal relations. These include the need for food, shelter, pay, and safe working conditions. RELATEDNESS NEEDS. These are needs that are satisfied by open communication and the exchange of thoughts and feelings with other organizational members. They correspond fairly closely to Maslow's belongingness needs and to those esteem needs that involve feedback from others. However, Alderfer stresses that relatedness needs are satisfied by open, accurate, honest interaction rather than by uncritical pleasantness. GROWTH NEEDS. These are needs that are fulfilled by strong personal involvement in the work setting. They involve the full utilization of one's skills and abilities and the creative development of new skills and abilities. Growth needs correspond to Maslow's need for self-actualization and the aspects of his esteem needs that concern achievement and responsibility, ERG theory. A three-level hierarchical need theory of motivation (existence, relatedness, growth) that allows for movement up and down the hierarchy. As you can see in Exhibit 5-3, Alderfer's need classification system does not represent a radical departure from that of Maslow. In addition, Alderfer agrees with Maslow that as lower-level needs are satisfied, the desire to have higher level needs satisfied will increase. Thus, as existence needs are fulfilled, relatedness needs gain motivational power. Alderfer explains this by arguing that as more "concrete" needs are satisfied, energy can be directed toward satisfying less concrete needs. Finally, Alderfer agrees with Maslow that the least concrete needs-growth needs, become more compelling and more desired as they are fulfilled. It is, of course, the differences between ERG theory and the need hierarchy that represent Alderfer's contribution to the understanding of motivation. First, unlike the need hierarchy, ERG theory does not assume that a lower-level need must be gratified before a less concrete need becomes operative. Thus, ERG theory does not propose a rigid hierarchy of needs. Some individuals, owing to background and experience, might seek relatedness or growth even though their existence needs are ungratified. Hence, ERG theory seems to account for a wide variety of individual differences in motive structure. Second, ERG theory assumes that if the higher-level needs are ungratified, individuals will increase their desire for the gratification of lower- level needs. Notice that this represents a radical departure from Maslow. According to Maslow, if esteem needs are strong but ungratified, a person will not revert to an interest in belongingness needs because these have necessarily already been gratified. (Remember, he argues that satisfied needs are not motivational.) According to Alderfer, however, the frustration of higher-order needs will lead workers to regress to a more concrete need category. For example, the software designer who is unable to establish rewarding social relationships with superiors or co- workers might increase his or her interest in fulfilling existence needs, perhaps by seeking a pay increase. Thus, according to Alderfer, an apparently satisfied need can act as a motivator by substituting for an unsatisfied need. Given the preceding description of ERG theory, we can identify its two major motivational premises as follows: The more lower-level needs are gratified, the more higher-level need satisfaction is desired. The less higher-level needs are gratified, the more lower-level need satisfaction is desired. McClelland's Theory of Needs Psychologist David McClelland spent several decades studying the human need structure and its implications for motivation. According to McClelland's theory of needs, needs reflect relatively stable personality characteristics that one acquires through early life experiences and exposure to selected aspects of one's society. Unlike Maslow and Alderfer, McClelland has not been interested in specifying a hierarchical relationship among needs. Rather, he has been more concerned with the specific behavioural consequences of needs. In other words, under what conditions are certain needs likely to result in particular patterns of motivation? The three needs that McClelland studied most have special relevance for organizational behaviour: needs for achievement, affiliation, and power.27 McClelland's theory of needs. A nonhierarchical need theory of motivation that outlines the conditions under which certain needs result in particular patterns of motivation. Individuals who are high in need for achievement (n Ach) have a strong desire to perform challenging tasks well. More specifically, they exhibit the following characteristics: A PREFERENCE FOR SITUATIONS IN WHICH PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY CAN BE TAKEN FOR OUTCOMES. Those high in n Ach do not prefer situations in which outcomes are determined by chance because success in such situations does not provide an experience of achievement. A TENDENCY TO SET MODERATELY DIFFICULT GOALS THAT PROVIDE FOR CALCULATED RISKS. Success with easy goals will provide little sense of achievement, while extremely difficult goals might never be reached. The calculation of successful risks is stimulating to the high-n Ach person. A DESIRE FOR PERFORMANCE FEEDBACK. Such feedback permits individuals with high n Ach to modify their goal attainment strategies to ensure success and signals them when success has been reached.28 Need for achievement. A strong desire to perform challenging tasks well. People who are high in n Ach are concerned with bettering their own performance or that of others. They are often concerned with innovation and long-term goal involvement. However, these things are not done to please others or to damage the interests of others. Rather, they are done because they are intrinsically satisfying. Thus, n Ach would appear to be an example of a growth or self-actualization need. People with a high need for power have a desire to influence others. Alotofpeople/Fotolia People who are high in need for affiliation (n Aff) have a strong desire to establish and maintain friendly, compatible interpersonal relationships. In other words, they like to like others, and they want others to like them! More specifically, they have an ability to learn social networking quickly and a tendency to communicate frequently with others, either face to face, by telephone, or in writing. Also, they prefer to avoid conflict and competition with others, and they sometimes exhibit strong conformity to the wishes of their friends. The n Aff motive is obviously an example of a belongingness or relatedness need. Need for affiliation

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock