Question: NEED ASAP! HELP! THIS IS A Case Analysis question!! No plagiarism. Please read the text first. Will give thumbs up 100% guaranteed. Please help. Thankyou!!

NEED ASAP! HELP!

THIS IS A Case Analysis question!! No plagiarism. Please read the text first. Will give thumbs up 100% guaranteed. Please help. Thankyou!!

Managing an organization strategically often requires it to expand internationally.

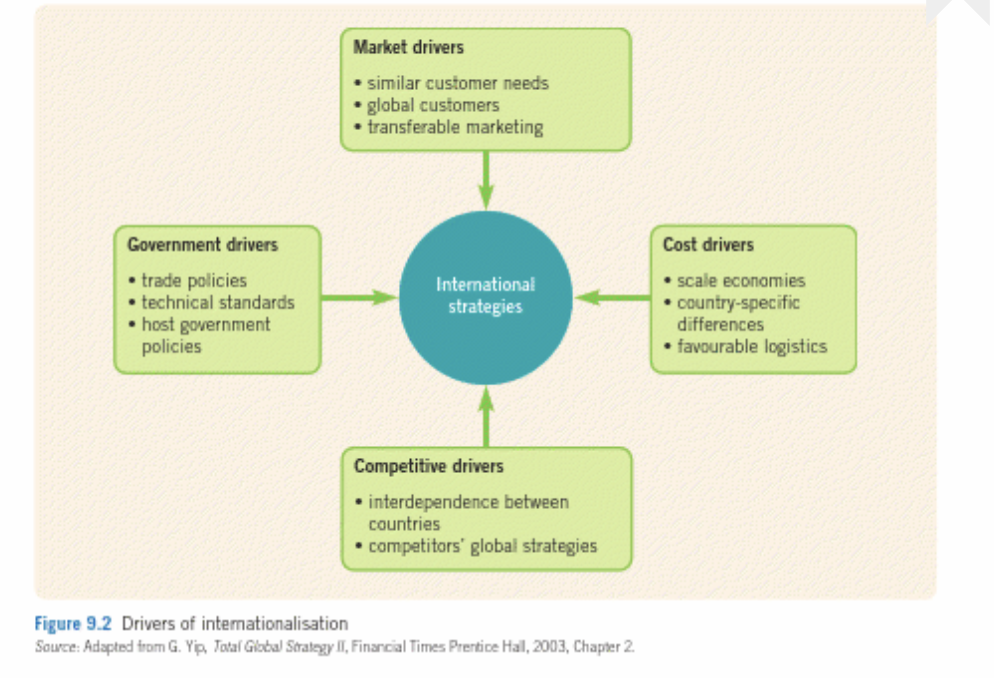

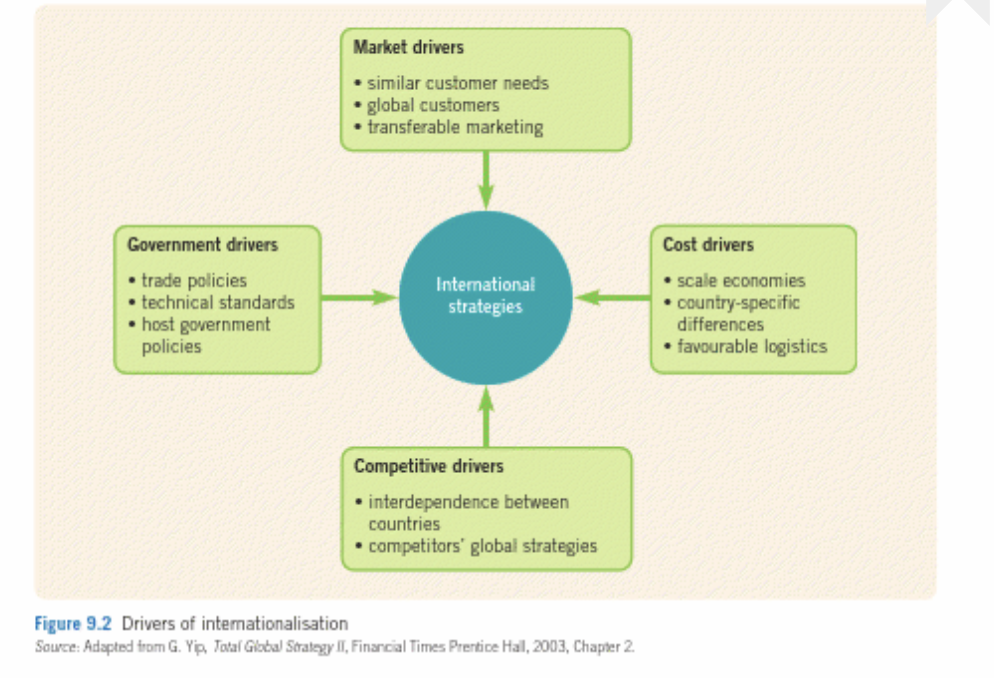

- Identify and discuss the drivers of internationalization (Figure 9.2) that apply to Samsungs extension of its chip manufacturing in Texas, USA, where it is investing $17 billion in Project Silicon Silver.

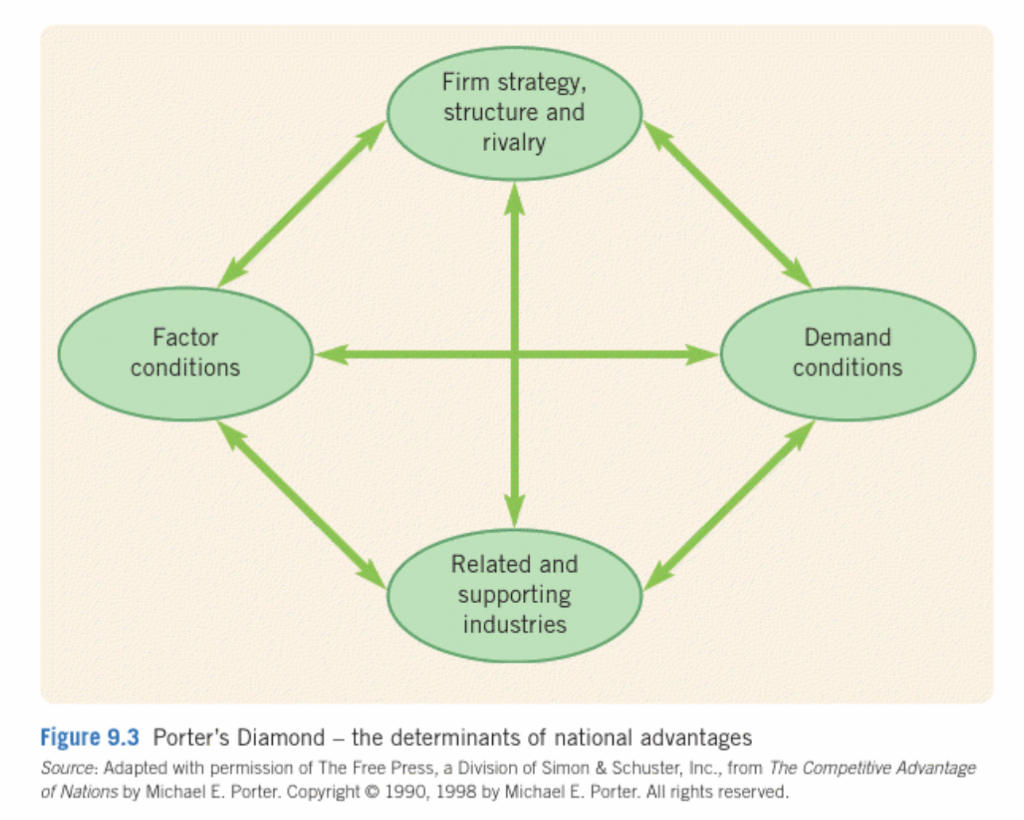

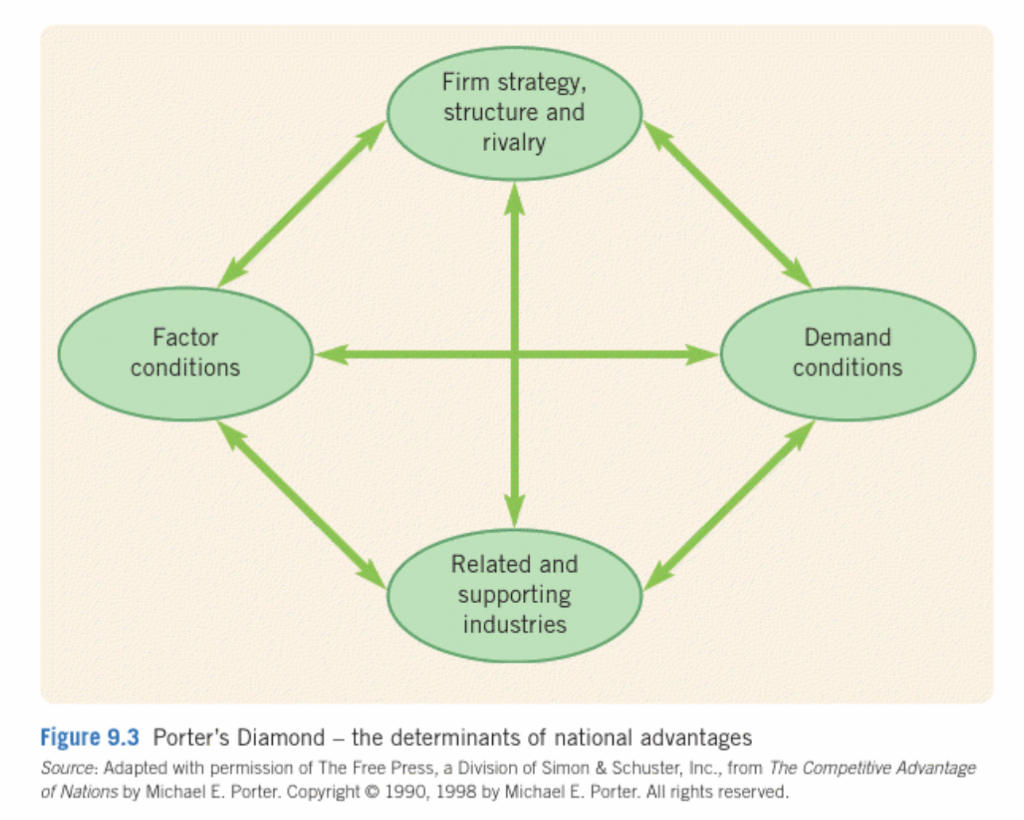

- Use Porters diamond (Figure 9.3) to identify and discuss determinants of national advantage (and any disadvantage) that matter to Samsungs expansion in Texas, USA.

- Build on your analysis to conclude with two recommendations for Samsung on the actions it should take with regards to its international expansion in chip manufacturing

FIGURE 9.2

FIGURE 9.3

CASE ANALYSIS:

Samsung Details Plans for $17 Billion Chip Facility in U.S.

Samsung Electronics Co. revealed additional details about its plans to build a cutting-edge semiconductor facility in the U.S. in a filing with the Texas government, making the disclosure as the Biden administration vows to make the security of the U.S. chip supply a national priority. The South Korean company plans to invest about $17 billion in its Project Silicon Silver and create about 1,800 jobs over the first ten years, according to an economic impact study prepared by a local consultant. Some $5.1 billion would go into buildings and property improvements, while $9.9 billion would be spent on machinery and equipment.

The filing with the Texas comptroller warned the chips project is highly competitive. Samsung is evaluating alternatives sites in Arizona and New York, as well as in Korea.

Because of its strong ties to the local community and the successful past 25 years of manufacturing in Texas, Samsung Austin Semiconductor would like to continue to invest in the city and the state, the study said.

Biden Putting Tech, Not Troops, at Core of U.S.-China Policy (1)

In their first weeks in office, Joe Bidens administration has emphasized the importance of advanced technologies, including semiconductors, artificial intelligence and next-generation networks. The president has ordered a global supply chain review for microchips as well as large-capacity batteries, pharmaceuticals and critical minerals and strategic materials such as rare earths.

MICROCHIP'S INDUSTRY

Samsung Electronics Co. revealed additional details about its plans to build a cutting-edge semiconductor facility in the U.S. in a filing with the Texas government, making the disclosure as the Biden administration vows to make the security of the U.S. chip supply a national priority.

The South Korean company plans to invest about $17 billion in its Project Silicon Silver and create about 1,800 jobs over the first ten years, according to an economic impact study prepared by a local consultant. Some $5.1 billion would go into buildings and property improvements, while $9.9 billion would be spent on machinery and equipment.

The filing with the Texas comptroller warned the chips project is highly competitive. Samsung is evaluating alternatives sites in Arizona and New York, as well as in Korea.

Because of its strong ties to the local community and the successful past 25 years of manufacturing in Texas, Samsung Austin Semiconductor would like to continue to invest in the city and the state, the study said.

Biden Putting Tech, Not Troops, at Core of U.S.-China Policy (1)

In their first weeks in office, Joe Bidens administration has emphasized the importance of advanced technologies, including semiconductors, artificial intelligence and next-generation networks. The president has ordered a global supply chain review for microchips as well as large-capacity batteries, pharmaceuticals and critical minerals and strategic materials such as rare earths.

Intels CEO reveals new strategy: Go big or go home

Intel's new CEO Pat Gelsinger laid out an ambitious and expensive agenda on Tuesday to get the chipmaker back on track after years of stumbles.

In his first strategic address since taking the top job at Intel last month, Gelsinger said the company would spend tens of billions of dollars on new manufacturing plants and double down on developing cutting-edge chip technologies.

"Innovation is alive and well, and we're far, far from done," Gelsinger told Fortune in an interview before his address. Noting some of the current shortages for semiconductors in key industries, Gelsinger said Intel's core business developing of processor chips "underlines every aspect of technology, which is becoming more pervasive in every aspect of human existence."

Wall Street has been hungry to hear from Gelsinger, a 30-year Intel veteran who left the company in 2009 and became CEO of software developer VMware a few years later. Intel's board, which passed him over for the top job in 2005, this year decided to welcome back the prodigal son following a rocky period under prior CEO Bob Swan. Intel's share price, which fell 17% last year, has jumped 19% since Gelsinger was named CEO in mid-January.

As part of Tuesday's announcements, Gelsinger said Intel would immediately move to build two new chip manufacturing plants in Arizona costing $20 billion, with plans for building additional plants in the U.S. and Europe over the next year.

And in a major departure from Intel's history, Gelsinger said Intel would build substantial extra capacity so it could become a major manufacturer of chips for other companies. That's the game plan rivals Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company and Samsung used to build their businesses and leapfrog Intel as suppliers to major chip designing companies like Apple, Samsung, and Nvidia.

Gelsinger also said Intel had "fully resolved" problems that delayed a major manufacturing improvement under prior CEO Swan. New processors for PCs using the technology, known as 7-nanometer, will be available for testing in the second quarter, he said. Still, given some of the mistakes and delays Intel made in the past, Gelsinger said Intel would need to outsource manufacturing of some of its upcoming products to rivals like TSMC, a stopgap strategy that prior CEO Swan had set in motion.

The bold strategy to regain technological superiority seized by competitors like Taiwan Semiconductor and Samsung shouldn't come as a surprise from Gelsinger, who spent much of his career at Intel under its fiery and legendary CEO Andy Grove.

"Things are moving rapidly as we restore execution, rebuild the Grovian culture, and I'll say the new Intel starts today," Gelsinger said with obvious enthusiasm. Declaring several times during his interview that "the geek is back," Gelsinger also said that Intel will resume holding annual industry conferences, starting in October with an event in San Francisco dubbed Intel On to showcase the company's upcoming tech improvements and work with partners.

Another part of Gelsinger's plan announced on Tuesday is to work more closely with IBM to develop the "foundational technologies" needed to make faster, more efficient chips.

The cost of spending more on new plants and accelerated research could sap funds Intel has typically used to buy back its shares over the past several years, a move that increases earnings per share but does little to improve the company's chips.

"I'm very confident that my board is 101% behind this," Gelsinger said when asked how Wall Street may react to his new plan. Investing in R&D, adding manufacturing capacity, and acquiring smaller companies "are the areas that will be the priorities for our capital investments," he added. "As the industry analysts and investors come to understand that and start to see the proof points behind that, it will be well supported in the markets as well."

Gelsinger said his overall strategy was guided not only by his prior 30-year history with the company but also by his subsequent 10-year tenure as CEO of software provider VMware.

"Every experience of my entire career is being used every single day," he said. "If there was an MRI taken on my brain, every neural pattern would be lit up in this experience."

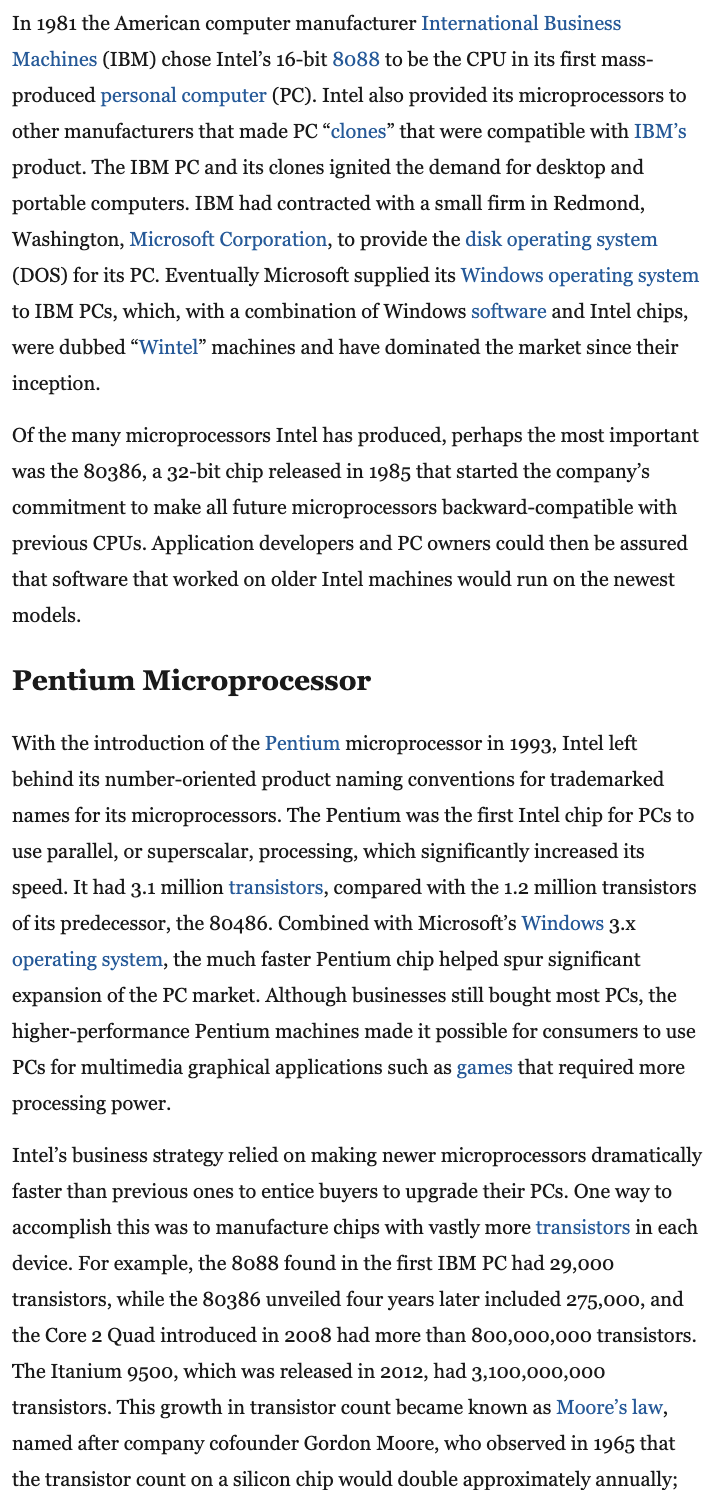

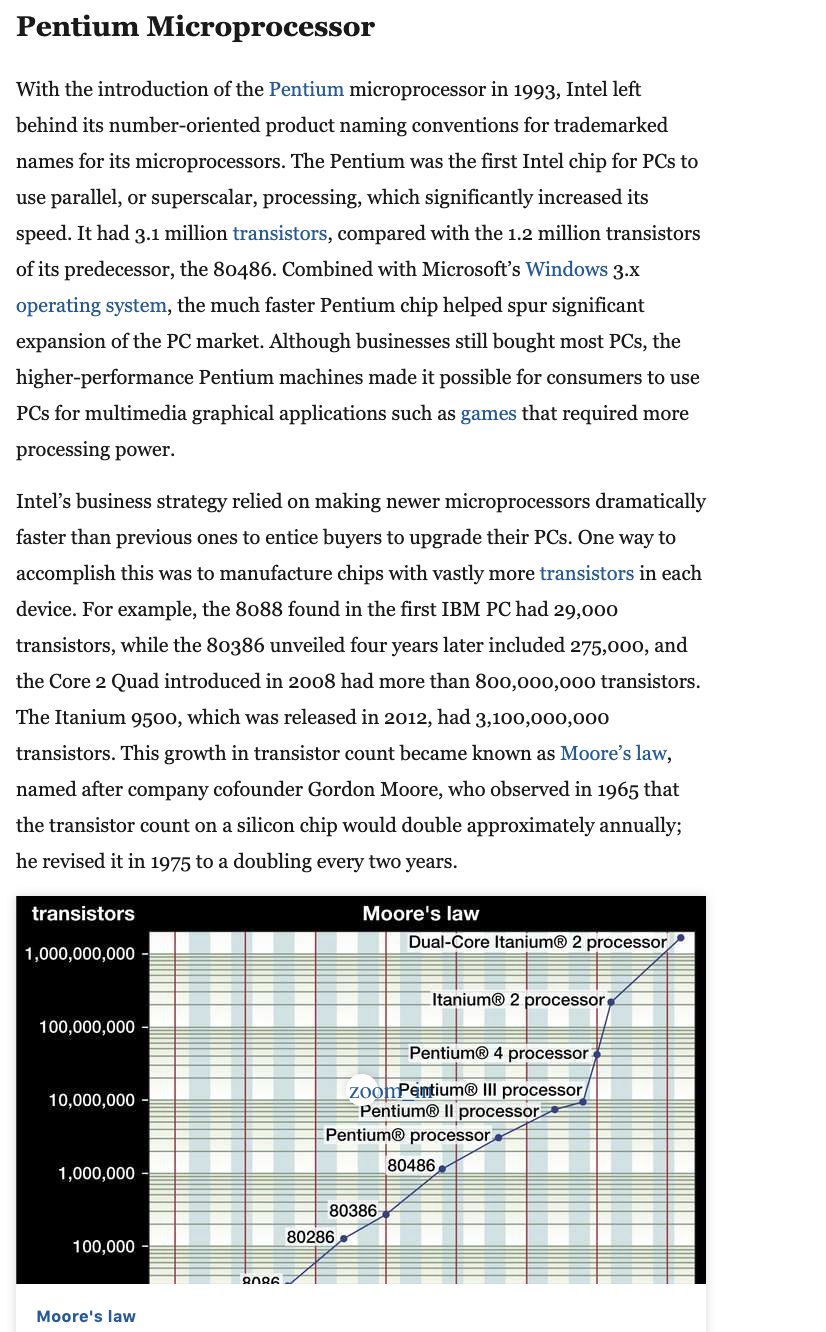

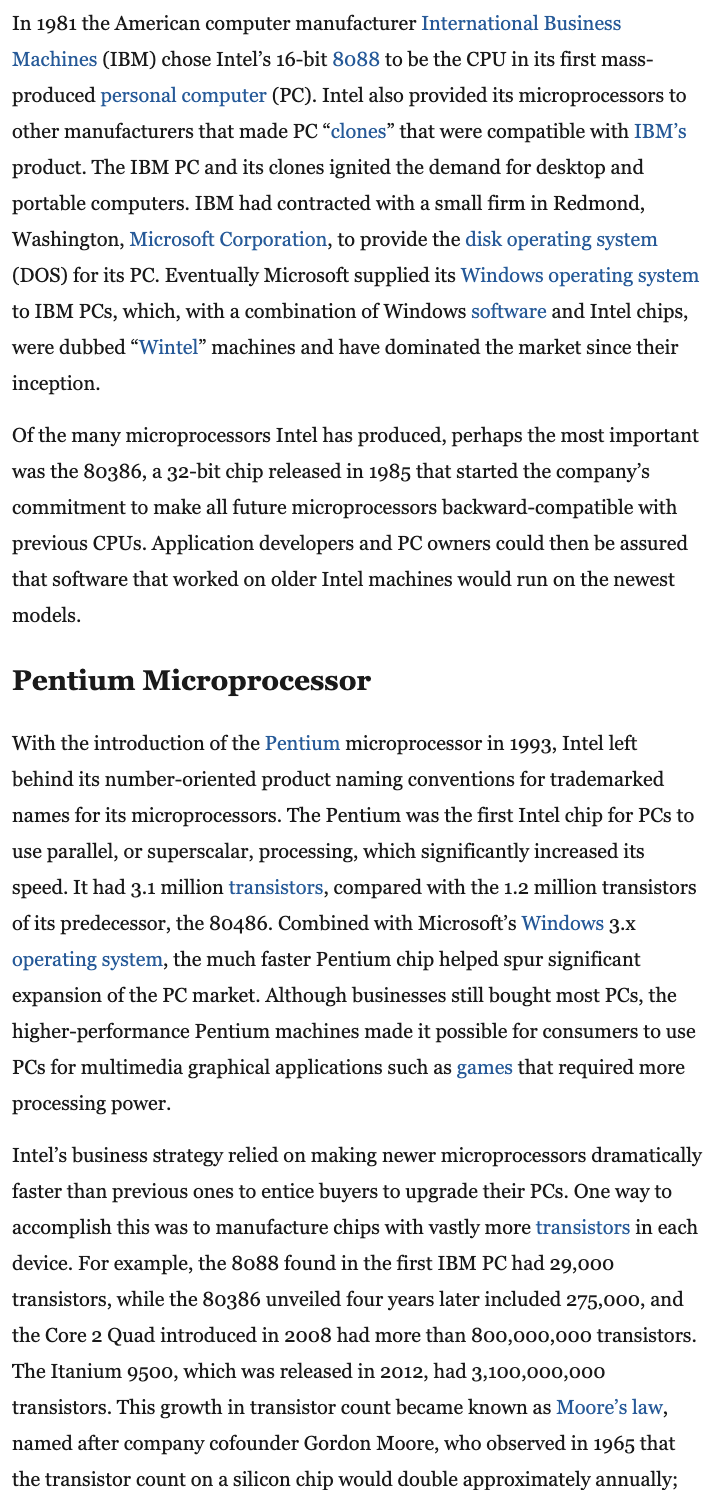

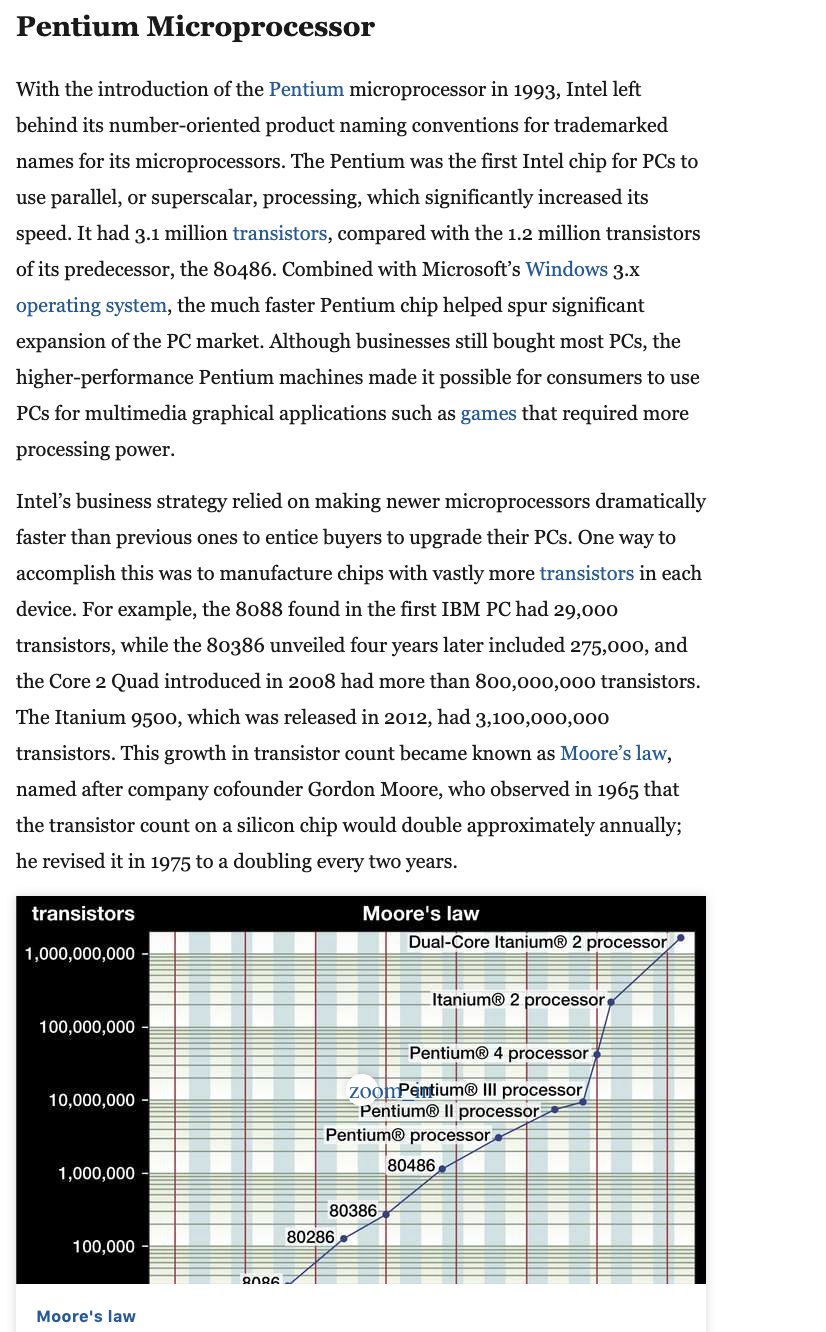

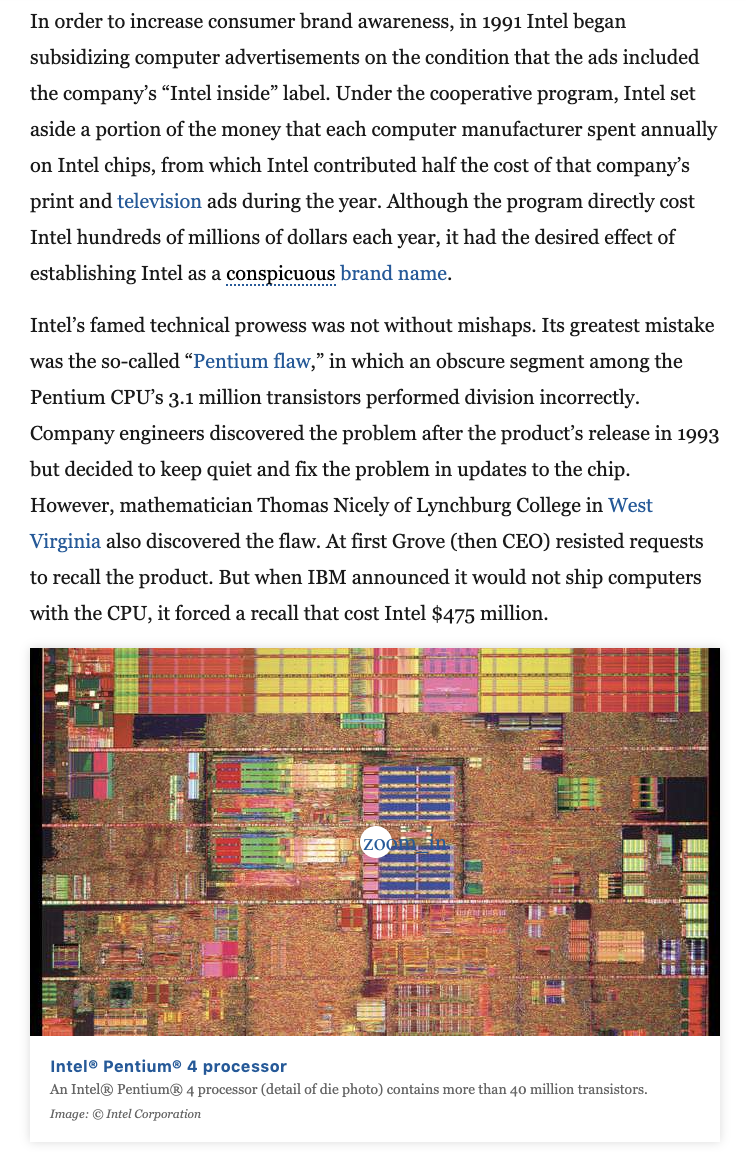

Has Intel's competitive advantage gone for good?

Firm strategy, structure and rivalry Factor conditions Demand conditions Related and supporting industries Figure 9.3 Porter's Diamond - the determinants of national advantages Source: Adapted with permission of The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., from The Competitive Advantage of Nations by Michael E. Porter. Copyright 1990, 1998 by Michael E. Porter. All rights reserved. Beginnings Intel was founded in July 1968 by American engineers Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore. Unlike the archetypal Silicon Valley start-up business with its fabled origins in a youthful founder's garage, Intel opened its doors with $2.5 million in funding arranged by Arthur Rock, the American financier who coined the term venture capitalist. Intel's founders were experienced, middle- aged technologists who had established reputations. Noyce was the coinventor in 1959 of the silicon integrated circuit when he was general manager of Fairchild Semiconductor, a division of Fairchild Camera and Instrument. Moore was the head of research and development at Fairchild Semiconductor. Immediately after founding Intel, Noyce and Moore recruited other Fairchild employees, including Hungarian-born American businessman Andrew Grove. Noyce, Moore, and Grove served as chairman and chief executive officer (CEO) in succession during the first three decades of the company's history. zo key Noyce, Robert Robert Noyce (left) and Gordon Moore in front of the Intel SC building, Santa Clara, California, 1970. Image: The Intel Free Press Early Products Intel's initial products were memory chips, including the world's first metal oxide semiconductor, the 1101, which did not sell well. However, its sibling, the 1103, a one-kilobit dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) chip, was successful and the first chip to store a significant amount of information. It was purchased first by the American technology company Honeywell Incorporated in 1970 to replace the core memory technology in its computers. Because DRAMs were cheaper and used less power than core memory, they quickly became the standard memory devices in computers worldwide. Early Products Intel's initial products were memory chips, including the world's first metal oxide semiconductor, the 1101, which did not sell well. However, its sibling, the 1103, a one-kilobit dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) chip, was successful and the first chip to store a significant amount of information. It was purchased first by the American technology company Honeywell Incorporated in 1970 to replace the core memory technology in its computers. Because DRAMs were cheaper and used less power than core memory, they quickly became the standard memory devices in computers worldwide. BOTH HIS FATHER AND MATERNAL GRANDFATHER WERE BAPTIST PREACHERS, and King followed them into religious ministry. Following its DRAM success, Intel became a public company in 1971. That same year Intel introduced the erasable programmable read-only memory (EPROM) chip, which was the company's most successful product line until 1985. Also in 1971 Intel engineers Ted Hoff, Federico Faggin, and Stan Mazor invented a general-purpose four-bit microprocessor and one of the first single-chip microprocessors, the 4004, under contract to the Japanese calculator manufacturer Nippon Calculating Machine Corporation, which let Intel retain all rights to the technology. Not all of Intel's early endeavours were successful. In 1972 management decided to enter the growing digital watch market by purchasing Microma. But Intel had no real understanding of consumers and sold the watchmaking company in 1978 at a loss of $15 million. In 1974 Intel controlled 82.9 percent of the DRAM chip market, but, with the rise of foreign semiconductor companies, the company's market share dipped to 1.3 percent by 1984. By that time, however, Intel had shifted from memory chips and become focused on its microprocessor business: in 1972 it produced the 8008, an eight-bit central processing unit (CPU); the 8080, which was 10 times faster than the 8008, came two years later; and in 1978 the company built its first 16-bit microprocessor, the 8086. In 1981 the American computer manufacturer International Business Machines (IBM) chose Intel's 16-bit 8088 to be the CPU in its first mass- produced personal computer (PC). Intel also provided its microprocessors to other manufacturers that made PCclones that were compatible with IBM's product. The IBM PC and its clones ignited the demand for desktop and portable computers. IBM had contracted with a small firm in Redmond, Washington, Microsoft Corporation, to provide the disk operating system (DOS) for its PC. Eventually Microsoft supplied its Windows operating system to IBM PCs, which, with a combination of Windows software and Intel chips, were dubbed Wintel" machines and have dominated the market since their inception. Of the many microprocessors Intel has produced, perhaps the most important was the 80386, a 32-bit chip released in 1985 that started the company's commitment to make all future microprocessors backward-compatible with previous CPUs. Application developers and PC owners could then be assured that software that worked on older Intel machines would run on the newest models. Pentium Microprocessor With the introduction of the Pentium microprocessor in 1993, Intel left behind its number-oriented product naming conventions for trademarked names for its microprocessors. The Pentium was the first Intel chip for PCs to use parallel, or superscalar, processing, which significantly increased its speed. It had 3.1 million transistors, compared with the 1.2 million transistors of its predecessor, the 80486. Combined with Microsoft's Windows 3.x operating system, the much faster Pentium chip helped spur significant expansion of the PC market. Although businesses still bought most PCs, the higher-performance Pentium machines made it possible for consumers to use PCs for multimedia graphical applications such as games that required more processing power. Intel's business strategy relied on making newer microprocessors dramatically faster than previous ones to entice buyers to upgrade their PCs. One way to accomplish this was to manufacture chips with vastly more transistors in each device. For example, the 8088 found in the first IBM PC had 29,000 transistors, while the 80386 unveiled four years later included 275,000, and the Core 2 Quad introduced in 2008 had more than 800,000,000 transistors. The Itanium 9500, which was released in 2012, had 3,100,000,000 transistors. This growth in transistor count became known as Moore's law, named after company cofounder Gordon Moore, who observed in 1965 that the transistor count on a silicon chip would double approximately annually; Pentium Microprocessor With the introduction of the Pentium microprocessor in 1993, Intel left behind its number-oriented product naming conventions for trademarked names for its microprocessors. The Pentium was the first Intel chip for PCs to use parallel, or superscalar, processing, which significantly increased its speed. It had 3.1 million transistors, compared with the 1.2 million transistors of its predecessor, the 80486. Combined with Microsoft's Windows 3.x operating system, the much faster Pentium chip helped spur significant expansion of the PC market. Although businesses still bought most PCs, the higher-performance Pentium machines made it possible for consumers to use PCs for multimedia graphical applications such as games that required more processing power. Intel's business strategy relied on making newer microprocessors dramatically faster than previous ones to entice buyers to upgrade their PCs. One way to accomplish this was to manufacture chips with vastly more transistors in each device. For example, the 8088 found in the first IBM PC had 29,000 transistors, while the 80386 unveiled four years later included 275,000, and the Core 2 Quad introduced in 2008 had more than 800,000,000 transistors. The Itanium 9500, which was released in 2012, had 3,100,000,000 transistors. This growth in transistor count became known as Moore's law, named after company cofounder Gordon Moore, who observed in 1965 that the transistor count on a silicon chip would double approximately annually; he revised it in 1975 to a doubling every two years. transistors Moore's law Dual-Core Itanium 2 processor 1,000,000,000 Itanium 2 processor 100,000,000 Pentium 4 processor 10,000,000 zoomPentium IIl processor Pentium II processor Pentium processor 80486 1,000,000 80386 80286 100,000 Qnga Moore's law In order to increase consumer brand awareness, in 1991 Intel began subsidizing computer advertisements on the condition that the ads included the company's Intel inside label. Under the cooperative program, Intel set aside a portion of the money that each computer manufacturer spent annually on Intel chips, from which Intel contributed half the cost of that company's print and television ads during the year. Although the program directly cost Intel hundreds of millions of dollars each year, it had the desired effect of establishing Intel as a conspicuous brand name. Intel's famed technical prowess was not without mishaps. Its greatest mistake was the so-called Pentium flaw, in which an obscure segment among the Pentium CPU's 3.1 million transistors performed division incorrectly. Company engineers discovered the problem after the product's release in 1993 but decided to keep quiet and fix the problem in updates to the chip. However, mathematician Thomas Nicely of Lynchburg College in West Virginia also discovered the flaw. At first Grove (then CEO) resisted requests to recall the product. But when IBM announced it would not ship computers with the CPU, it forced a recall that cost Intel $475 million. zoo Intel Pentium 4 processor An Intel Pentium 4 processor (detail of die photo) contains more than 40 million transistors. Image: Intel Corporation ZOO Intel Pentium 4 processor An Intel Pentium 4 processor (detail of die photo) contains more than 40 million transistors. Image: Intel Corporation Although bruised by the Pentium fiasco, the combination of Intel technology with Microsoft software continued to crush the competition. Rival products from the semiconductor company Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), the wireless communications company Motorola, the computer workstation manufacturer Sun Microsystems, and others rarely threatened Intel's market share. As a result, the Wintel duo consistently faced accusations of being monopolies. In 1999 Microsoft was found guilty in a U.S. district court of being a monopolist after being sued by the Department of Justice, while in 2009 the European Union fined Intel $1.45 billion for alleged monopolistic actions. In 2009 Intel also paid AMD $1.25 billion to settle a decades-long legal dispute in which AMD accused Intel of pressuring PC makers not to use the former's chips. Expansion And Other Developments By the mid-1990s Intel had expanded beyond the chip business. Large PC makers, such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard, were able to design and manufacture Intel-based computers for their markets. However, Intel wanted other, smaller PC makers to get their products and, therefore, Intel's chips to market faster, so it began to design and build motherboards that contained all the essential parts of the computer, including graphics and networking chips. By 1995 the company was selling more than 10 million motherboards to PC makers, about 40 percent of the overall PC market. In the early 21st century the Taiwan-based manufacturer ASUSTeK had surpassed Intel as the leading maker of PC motherboards. Expansion And Other Developments By the mid-1990s Intel had expanded beyond the chip business. Large PC makers, such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard, were able to design and manufacture Intel-based computers for their markets. However, Intel wanted other, smaller PC makers to get their products and, therefore, Intel's chips to market faster, so it began to design and build motherboards that contained all the essential parts of the computer, including graphics and networking chips. By 1995 the company was selling more than 10 million motherboards to PC makers, about 40 percent of the overall PC market. In the early 21st century the Taiwan-based manufacturer ASUSTeK had surpassed Intel as the leading maker of PC motherboards. By the end of the century, Intel and compatible chips from companies like AMD were found in every PC except Apple Inc.'s Macintosh, which had used CPUs from Motorola since 1984. Craig Barrett, who succeeded Grove as Intel CEO in 1998, was able to close that gap. In 2005 Apple CEO Steven Jobs shocked the industry when he announced future Apple PCs would use Intel CPUs. Therefore, with the exception of some high-performance computers, called servers, and mainframes, Intel and Intel-compatible microprocessors can be found in virtually every PC, and the company dominated the CPU market in the early 21st century. Paul Otellini succeeded Barrett as Intel's CEO in 2005, and four years later Jane Shaw replaced Barrett as chairman. She held the post until 2012, when she was succeeded by Andy Bryant. The following year Brian Krzanich became CEO. In 2019 chief financial officer Bob Swan became CEO, and Intel ranked 43 on the Fortune 500 list of the largest American companies. Has Intel's competitive advantage gone for good? Oakley, Phil.Investors Chronicle; London (Sep 25, 2020): 58. Full text Abstract/Details Abstract Translate Intel, once the dominant player in the global microprocessing chip industry, is a fascinating study in how a market leader can lose its way, with valuable lessons for investors. The huge profits it produced allowed Intel to fund a very large research and development budget that was many times bigger than its competitors and allowed it to defend and enhance its market-leading position. The Company is still able to push through price increases in its PC business, which in a different world might be seen as a sign of strength but could now be seen as a bad thing given the growing strength of AMD. [...]its shares now look to be extremely cheap compared with Full Text Translate It's hard for great companies to stay great. Have Intel's days of greatness gone for good? There can be no doubt that Intel (US:INTC) has been a great business. Whether it can continue to be one is by no means certain. Great companies only make great longterm investments if they stay great. A failure to defend a hard-won position of competitive strength in an industry can leave investors frustrated and disappointed. This looks like the position that Intel and its shareholders find themselves now. One of the big lessons that investors have had drummed into them in recent years is the success they can have in buying the shares of great businesses. These are businesses that succeed by giving their customers what they want and doing it better than anyone one else. By working hard to create a position of competitive strength - even dominance - and then growing revenues and profits, the gains in business value and the rewards to shareholders can mount up. One of the golden rules in business economics is that high levels of profitability tend to attract competition. Understanding how a market leader maintains its position and why it might lose it is very important. Intel, once the dominant player in the global microprocessing chip industry, is a fascinating study in how a market leader can lose its way, with valuable lessons for investors. It now seems to be at a tipping point. It has made mistakes and has lost a lot of its competitive strength. Can it get it back? What made Intel great? For years, Intel was the world's largest chipmaker. It developed the x86 architecture that formed the basis for the microprocessors that made up the central processing unit (CPU) that went into desktop and laptop computers. It was the main beneficiary of Moore's Law, which in simple terms refers to the number of transistors on an integrated circuit of a microchip doubling every two years. The company kept on making better performing chips compared with previous versions of its own products and that of its competitors. This allowed it to dominate the personal computer (PC) chip market and build a business of massive scale. Its strategy of manufacturing as well as designing chips gave it huge scale economies and competitive strength. The combination of dominance and scale created a very profitable and cash-generative business with significant pricing power. The huge profits it produced allowed Intel to fund a very large research and development budget that was many times bigger than its competitors and allowed it to defend and enhance its market-leading position. If you were looking at Intel 20 years ago you could be forgiven for thinking that it looked unstoppable. However, the slowdown in its core PC market and a shift in technology has changed this. Intel has been slow to adapt to a changing world and is arguably guilty of being complacent and milking its PC business for cash while its competitors got on with stealing the battleground from it. The company looks as though it has been hunted down and now has to turn itself into a hunter again to get back on track. Why has it gone wrong for Intel? A failure to innovate and capitalise on new trends Intel has made a lot of mistakes in the past decade. Arguably one of the biggest ones has been to pull back from developing chips for the mobile devices market. The company initially targeted this market, but gave up on it. As people and businesses move away from doing things sitting at a desk to doing things on the move or on location, mobile devices have become the product of choice. Instead of the chip market for these products being captured by Intel it has gone to other companies such as Qualcomm (US:QCOM) and ARM Holdings. The loss of production leadership One of Intel's biggest strengths was its ability to design and manufacture the best chips and bring them to market. The quality of chips is weighed up by looking at how much power they offer relative to their size. The trend has been for the latest chips to be smaller while offering more power than their predecessors. Chip size is measured in nanometers (nm) and Intel has made some big errors in producing smaller chips. It was slow to release its 10nm chip and is now around a year behind schedule with its release date for 7nm chips. This has seen the Company cede its marketleadership to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (Tai:2330), which has its 7nm chips on sale and could even move to 3nm chips in the next few years. Investors rightly worry that Intel is a long way behind TSMC and may not be able to catch up. In the meantime, TSMC is busy making its superior chips for Intel's competitors. What may be even more worrying is Intel's admission that it may have to outsource chip production given its current problems of getting new products to market. Its vertical integration (design and manufacturing) has been seen as one of its key competitive strengths and losing it may weaken it. The rise of Nvidia and the resurgence of AMD While some of intel's current woes appear to have been self inflicted. There can be no doubt that Its competitors have really upped their game and stolen a march on it. The most notable is Nvidia (US:NVDA), which used to be seen as a niche player making high-end graphics processors for video gaming devices. Nvidia has taken the technology of its graphical processing units (GPUs) and applied it to fast-growing applications such as the data centres used in cloud computing and artificial intelligence. Nvidia's move to buy ARM will give it exposure to mobile technology and also possibly put it into a position to threaten Intel's desktop and laptop markets. It is possible that a combination of Nvidia and ARM could create a one-stop shop for a variety of chip applications that no one can currently match. A real worry for Intel is that an Nvidia/ ARM combination will be in a great position to exploit the current and growing trends in technology uses and the chip demand that comes from them. Edge computing is a big theme, where the storage and use of data increasingly needs to be close to where it is being used rather than being sent back to another remote location. This and the internet of things (IOT), where lots of devices are connected to the internet and talk to each other, arguably favours the likes of Nvidia and ARM with their positions in mobile chip technology and artificial intelligence built in. Advanced Micro Devices (US:AMD) had been competing with Intel for a long time without much success, but now seems to have taken a big step up with its product offer. The concern for Intel now is that AMD's chips are much better and considerably cheaper than its own and not just in the PC market. Alphabet's (US:GOOGL) Google is using AMD chips in its cloud data centres, while Microsoft (US:MSFT) and Amazon (US:AMZN) are also using a lot of them these days. Will big PC companies such as Dell and Lenovo do the same? Both Nvidia and AMD just concentrate on chip design and have outsourced production of their chips to Taiwan Semiconductor. This makes sense as they are not in a position to match Intel's scale economies. Instead, they have focused on innovation and making great products, and are having a lot of success Big customers are designing their own chips It seems that there are customers who no longer need Intel. Apple (US:AAPL) has dumped Intel and is designing its own chips to use in its Macbook computers using ARM technology. Amazon is also using ARM. Big customers that would have previously turned to Intel for their chip needs may now choose to design their own using someone else's technology and get TSMC to produce them. Intel should not be written offjust yet Intel is clearly facing a lot of difficulties right now and resembles a wounded giant, but it is far from dead. It still has immense scale and financial strength that can be put to good use. It is developing new artificial intelligence technology for use in areas such as autonomous driving. It also has some good products to sell into 5G mobile networks. The Company's data centre business is performing really well, with revenue growth of 43 per cent in the year to date. However, its PC business, with the exception of notebooks, looks to be ex-growth. The Company is still able to push through price increases in its PC business, which in a different world might be seen as a sign of strength but could now be seen as a bad thing given the growing strength of AMD. Are Intel shares a classic value trap? Intel's problems are very well known. As a result, its shares now look to be extremely cheap compared with its competitors. The Company also still scores very well when looking at key financial performance ratios such as operating margin, return on operating capital employed (ROOCE) and free cash flow margin. For those of you who are familiar with Joel Greenblatt's Magic Formula, which tries to identify businesses with high returns on assets combined with a cheap valuation, then Intel shares - on just over 10 times forecast one-year earnings - look very attractive right now. Intel vs competitors The main drawback with the Magic Formula approach is that it ignores the vital ingredient to achieve good investment returns from owning shares: the ability of a Company to grow. This is where the investment case for Intel seems to fall down at the moment. Intel forecasts With its production problems and fierce competitive backdrop, it looks as though there is very little growth to come from Intel over the next couple of years. Yet the Company is still expected to produce prodigious amounts of free cash flow and arguably doesn't need to grow much to justify its current stock market valuation. However, without some kind of positive newsflow, I struggle to see what drives the shares higher from its current level. There also has to be a real concern that its competitive position continues to weaken. Technology shares have been running hot for a good while now, but Intel is proof that they still have to face up to the same strategic and competitive issues as other businesses. Intel's loss of dominance is also a stark reminder to investors that great businesses need to work hard and smart to stay that way. Owning a share of a business that fails to do this is unlikely to do them much good. Firm strategy, structure and rivalry Factor conditions Demand conditions Related and supporting industries Figure 9.3 Porter's Diamond - the determinants of national advantages Source: Adapted with permission of The Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., from The Competitive Advantage of Nations by Michael E. Porter. Copyright 1990, 1998 by Michael E. Porter. All rights reserved. Beginnings Intel was founded in July 1968 by American engineers Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore. Unlike the archetypal Silicon Valley start-up business with its fabled origins in a youthful founder's garage, Intel opened its doors with $2.5 million in funding arranged by Arthur Rock, the American financier who coined the term venture capitalist. Intel's founders were experienced, middle- aged technologists who had established reputations. Noyce was the coinventor in 1959 of the silicon integrated circuit when he was general manager of Fairchild Semiconductor, a division of Fairchild Camera and Instrument. Moore was the head of research and development at Fairchild Semiconductor. Immediately after founding Intel, Noyce and Moore recruited other Fairchild employees, including Hungarian-born American businessman Andrew Grove. Noyce, Moore, and Grove served as chairman and chief executive officer (CEO) in succession during the first three decades of the company's history. zo key Noyce, Robert Robert Noyce (left) and Gordon Moore in front of the Intel SC building, Santa Clara, California, 1970. Image: The Intel Free Press Early Products Intel's initial products were memory chips, including the world's first metal oxide semiconductor, the 1101, which did not sell well. However, its sibling, the 1103, a one-kilobit dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) chip, was successful and the first chip to store a significant amount of information. It was purchased first by the American technology company Honeywell Incorporated in 1970 to replace the core memory technology in its computers. Because DRAMs were cheaper and used less power than core memory, they quickly became the standard memory devices in computers worldwide. Early Products Intel's initial products were memory chips, including the world's first metal oxide semiconductor, the 1101, which did not sell well. However, its sibling, the 1103, a one-kilobit dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) chip, was successful and the first chip to store a significant amount of information. It was purchased first by the American technology company Honeywell Incorporated in 1970 to replace the core memory technology in its computers. Because DRAMs were cheaper and used less power than core memory, they quickly became the standard memory devices in computers worldwide. BOTH HIS FATHER AND MATERNAL GRANDFATHER WERE BAPTIST PREACHERS, and King followed them into religious ministry. Following its DRAM success, Intel became a public company in 1971. That same year Intel introduced the erasable programmable read-only memory (EPROM) chip, which was the company's most successful product line until 1985. Also in 1971 Intel engineers Ted Hoff, Federico Faggin, and Stan Mazor invented a general-purpose four-bit microprocessor and one of the first single-chip microprocessors, the 4004, under contract to the Japanese calculator manufacturer Nippon Calculating Machine Corporation, which let Intel retain all rights to the technology. Not all of Intel's early endeavours were successful. In 1972 management decided to enter the growing digital watch market by purchasing Microma. But Intel had no real understanding of consumers and sold the watchmaking company in 1978 at a loss of $15 million. In 1974 Intel controlled 82.9 percent of the DRAM chip market, but, with the rise of foreign semiconductor companies, the company's market share dipped to 1.3 percent by 1984. By that time, however, Intel had shifted from memory chips and become focused on its microprocessor business: in 1972 it produced the 8008, an eight-bit central processing unit (CPU); the 8080, which was 10 times faster than the 8008, came two years later; and in 1978 the company built its first 16-bit microprocessor, the 8086. In 1981 the American computer manufacturer International Business Machines (IBM) chose Intel's 16-bit 8088 to be the CPU in its first mass- produced personal computer (PC). Intel also provided its microprocessors to other manufacturers that made PCclones that were compatible with IBM's product. The IBM PC and its clones ignited the demand for desktop and portable computers. IBM had contracted with a small firm in Redmond, Washington, Microsoft Corporation, to provide the disk operating system (DOS) for its PC. Eventually Microsoft supplied its Windows operating system to IBM PCs, which, with a combination of Windows software and Intel chips, were dubbed Wintel" machines and have dominated the market since their inception. Of the many microprocessors Intel has produced, perhaps the most important was the 80386, a 32-bit chip released in 1985 that started the company's commitment to make all future microprocessors backward-compatible with previous CPUs. Application developers and PC owners could then be assured that software that worked on older Intel machines would run on the newest models. Pentium Microprocessor With the introduction of the Pentium microprocessor in 1993, Intel left behind its number-oriented product naming conventions for trademarked names for its microprocessors. The Pentium was the first Intel chip for PCs to use parallel, or superscalar, processing, which significantly increased its speed. It had 3.1 million transistors, compared with the 1.2 million transistors of its predecessor, the 80486. Combined with Microsoft's Windows 3.x operating system, the much faster Pentium chip helped spur significant expansion of the PC market. Although businesses still bought most PCs, the higher-performance Pentium machines made it possible for consumers to use PCs for multimedia graphical applications such as games that required more processing power. Intel's business strategy relied on making newer microprocessors dramatically faster than previous ones to entice buyers to upgrade their PCs. One way to accomplish this was to manufacture chips with vastly more transistors in each device. For example, the 8088 found in the first IBM PC had 29,000 transistors, while the 80386 unveiled four years later included 275,000, and the Core 2 Quad introduced in 2008 had more than 800,000,000 transistors. The Itanium 9500, which was released in 2012, had 3,100,000,000 transistors. This growth in transistor count became known as Moore's law, named after company cofounder Gordon Moore, who observed in 1965 that the transistor count on a silicon chip would double approximately annually; Pentium Microprocessor With the introduction of the Pentium microprocessor in 1993, Intel left behind its number-oriented product naming conventions for trademarked names for its microprocessors. The Pentium was the first Intel chip for PCs to use parallel, or superscalar, processing, which significantly increased its speed. It had 3.1 million transistors, compared with the 1.2 million transistors of its predecessor, the 80486. Combined with Microsoft's Windows 3.x operating system, the much faster Pentium chip helped spur significant expansion of the PC market. Although businesses still bought most PCs, the higher-performance Pentium machines made it possible for consumers to use PCs for multimedia graphical applications such as games that required more processing power. Intel's business strategy relied on making newer microprocessors dramatically faster than previous ones to entice buyers to upgrade their PCs. One way to accomplish this was to manufacture chips with vastly more transistors in each device. For example, the 8088 found in the first IBM PC had 29,000 transistors, while the 80386 unveiled four years later included 275,000, and the Core 2 Quad introduced in 2008 had more than 800,000,000 transistors. The Itanium 9500, which was released in 2012, had 3,100,000,000 transistors. This growth in transistor count became known as Moore's law, named after company cofounder Gordon Moore, who observed in 1965 that the transistor count on a silicon chip would double approximately annually; he revised it in 1975 to a doubling every two years. transistors Moore's law Dual-Core Itanium 2 processor 1,000,000,000 Itanium 2 processor 100,000,000 Pentium 4 processor 10,000,000 zoomPentium IIl processor Pentium II processor Pentium processor 80486 1,000,000 80386 80286 100,000 Qnga Moore's law In order to increase consumer brand awareness, in 1991 Intel began subsidizing computer advertisements on the condition that the ads included the company's Intel inside label. Under the cooperative program, Intel set aside a portion of the money that each computer manufacturer spent annually on Intel chips, from which Intel contributed half the cost of that company's print and television ads during the year. Although the program directly cost Intel hundreds of millions of dollars each year, it had the desired effect of establishing Intel as a conspicuous brand name. Intel's famed technical prowess was not without mishaps. Its greatest mistake was the so-called Pentium flaw, in which an obscure segment among the Pentium CPU's 3.1 million transistors performed division incorrectly. Company engineers discovered the problem after the product's release in 1993 but decided to keep quiet and fix the problem in updates to the chip. However, mathematician Thomas Nicely of Lynchburg College in West Virginia also discovered the flaw. At first Grove (then CEO) resisted requests to recall the product. But when IBM announced it would not ship computers with the CPU, it forced a recall that cost Intel $475 million. zoo Intel Pentium 4 processor An Intel Pentium 4 processor (detail of die photo) contains more than 40 million transistors. Image: Intel Corporation ZOO Intel Pentium 4 processor An Intel Pentium 4 processor (detail of die photo) contains more than 40 million transistors. Image: Intel Corporation Although bruised by the Pentium fiasco, the combination of Intel technology with Microsoft software continued to crush the competition. Rival products from the semiconductor company Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), the wireless communications company Motorola, the computer workstation manufacturer Sun Microsystems, and others rarely threatened Intel's market share. As a result, the Wintel duo consistently faced accusations of being monopolies. In 1999 Microsoft was found guilty in a U.S. district court of being a monopolist after being sued by the Department of Justice, while in 2009 the European Union fined Intel $1.45 billion for alleged monopolistic actions. In 2009 Intel also paid AMD $1.25 billion to settle a decades-long legal dispute in which AMD accused Intel of pressuring PC makers not to use the former's chips. Expansion And Other Developments By the mid-1990s Intel had expanded beyond the chip business. Large PC makers, such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard, were able to design and manufacture Intel-based computers for their markets. However, Intel wanted other, smaller PC makers to get their products and, therefore, Intel's chips to market faster, so it began to design and build motherboards that contained all the essential parts of the computer, including graphics and networking chips. By 1995 the company was selling more than 10 million motherboards to PC makers, about 40 percent of the overall PC market. In the early 21st century the Taiwan-based manufacturer ASUSTeK had surpassed Intel as the leading maker of PC motherboards. Expansion And Other Developments By the mid-1990s Intel had expanded beyond the chip business. Large PC makers, such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard, were able to design and manufacture Intel-based computers for their markets. However, Intel wanted other, smaller PC makers to get their products and, therefore, Intel's chips to market faster, so it began to design and build motherboards that contained all the essential parts of the computer, including graphics and networking chips. By 1995 the company was selling more than 10 million motherboards to PC makers, about 40 percent of the overall PC market. In the early 21st century the Taiwan-based manufacturer ASUSTeK had surpassed Intel as the leading maker of PC motherboards. By the end of the century, Intel and compatible chips from companies like AMD were found in every PC except Apple Inc.'s Macintosh, which had used CPUs from Motorola since 1984. Craig Barrett, who succeeded Grove as Intel CEO in 1998, was able to close that gap. In 2005 Apple CEO Steven Jobs shocked the industry when he announced future Apple PCs would use Intel CPUs. Therefore, with the exception of some high-performance computers, called servers, and mainframes, Intel and Intel-compatible microprocessors can be found in virtually every PC, and the company dominated the CPU market in the early 21st century. Paul Otellini succeeded Barrett as Intel's CEO in 2005, and four years later Jane Shaw replaced Barrett as chairman. She held the post until 2012, when she was succeeded by Andy Bryant. The following year Brian Krzanich became CEO. In 2019 chief financial officer Bob Swan became CEO, and Intel ranked 43 on the Fortune 500 list of the largest American companies. Has Intel's competitive advantage gone for good? Oakley, Phil.Investors Chronicle; London (Sep 25, 2020): 58. Full text Abstract/Details Abstract Translate Intel, once the dominant player in the global microprocessing chip industry, is a fascinating study in how a market leader can lose its way, with valuable lessons for investors. The huge profits it produced allowed Intel to fund a very large research and development budget that was many times bigger than its competitors and allowed it to defend and enhance its market-leading position. The Company is still able to push through price increases in its PC business, which in a different world might be seen as a sign of strength but could now be seen as a bad thing given the growing strength of AMD. [...]its shares now look to be extremely cheap compared with Full Text Translate It's hard for great companies to stay great. Have Intel's days of greatness gone for good? There can be no doubt that Intel (US:INTC) has been a great business. Whether it can continue to be one is by no means certain. Great companies only make great longterm investments if they stay great. A failure to defend a hard-won position of competitive strength in an industry can leave investors frustrated and disappointed. This looks like the position that Intel and its shareholders find themselves now. One of the big lessons that investors have had drummed into them in recent years is the success they can have in buying the shares of great businesses. These are businesses that succeed by giving their customers what they want and doing it better than anyone one else. By working hard to create a position of competitive strength - even dominance - and then growing revenues and profits, the gains in business value and the rewards to shareholders can mount up. One of the golden rules in business economics is that high levels of profitability tend to attract competition. Understanding how a market leader maintains its position and why it might lose it is very important. Intel, once the dominant player in the global microprocessing chip industry, is a fascinating study in how a market leader can lose its way, with valuable lessons for investors. It now seems to be at a tipping point. It has made mistakes and has lost a lot of its competitive strength. Can it get it back? What made Intel great? For years, Intel was the world's largest chipmaker. It developed the x86 architecture that formed the basis for the microprocessors that made up the central processing unit (CPU) that went into desktop and laptop computers. It was the main beneficiary of Moore's Law, which in simple terms refers to the number of transistors on an integrated circuit of a microchip doubling every two years. The company kept on making better performing chips compared with previous versions of its own products and that of its competitors. This allowed it to dominate the personal computer (PC) chip market and build a business of massive scale. Its strategy of manufacturing as well as designing chips gave it huge scale economies and competitive strength. The combination of dominance and scale created a very profitable and cash-generative business with significant pricing power. The huge profits it produced allowed Intel to fund a very large research and development budget that was many times bigger than its competitors and allowed it to defend and enhance its market-leading position. If you were looking at Intel 20 years ago you could be forgiven for thinking that it looked unstoppable. However, the slowdown in its core PC market and a shift in technology has changed this. Intel has been slow to adapt to a changing world and is arguably guilty of being complacent and milking its PC business for cash while its competitors got on with stealing the battleground from it. The company looks as though it has been hunted down and now has to turn itself into a hunter again to get back on track. Why has it gone wrong for Intel? A failure to innovate and capitalise on new trends Intel has made a lot of mistakes in the past decade. Arguably one of the biggest ones has been to pull back from developing chips for the mobile devices market. The company initially targeted this market, but gave up on it. As people and businesses move away from doing things sitting at a desk to doing things on the move or on location, mobile devices have become the product of choice. Instead of the chip market for these products being captured by Intel it has gone to other companies such as Qualcomm (US:QCOM) and ARM Holdings. The loss of production leadership One of Intel's biggest strengths was its ability to design and manufacture the best chips and bring them to market. The quality of chips is weighed up by looking at how much power they offer relative to their size. The trend has been for the latest chips to be smaller while offering more power than their predecessors. Chip size is measured in nanometers (nm) and Intel has made some big errors in producing smaller chips. It was slow to release its 10nm chip and is now around a year behind schedule with its release date for 7nm chips. This has seen the Company cede its marketleadership to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (Tai:2330), which has its 7nm chips on sale and could even move to 3nm chips in the next few years. Investors rightly worry that Intel is a long way behind TSMC and may not be able to catch up. In the meantime, TSMC is busy making its superior chips for Intel's competitors. What may be even more worrying is Intel's admission that it may have to outsource chip production given its current problems of getting new products to market. Its vertical integration (design and manufacturing) has been seen as one of its key competitive strengths and losing it may weaken it. The rise of Nvidia and the resurgence of AMD While some of intel's current woes appear to have been self inflicted. There can be no doubt that Its competitors have really upped their game and stolen a march on it. The most notable is Nvidia (US:NVDA), which used to be seen as a niche player making high-end graphics processors for video gaming devices. Nvidia has taken the technology of its graphical processing units (GPUs) and applied it to fast-growing applications such as the data centres used in cloud computing and artificial intelligence. Nvidia's move to buy ARM will give it exposure to mobile technology and also possibly put it into a position to threaten Intel's desktop and laptop markets. It is possible that a combination of Nvidia and ARM could create a one-stop shop for a variety of chip applications that no one can currently match. A real worry for Intel is that an Nvidia/ ARM combination will be in a great position to exploit the current and growing trends in technology uses and the chip demand that comes from them. Edge computing is a big theme, where the storage and use of data increasingly needs to be close to where it is being used rather than being sent back to another remote location. This and the internet of things (IOT), where lots of devices are connected to the internet and talk to each other, arguably favours the likes of Nvidia and ARM with their positions in mobile chip technology and artificial intelligence built in. Advanced Micro Devices (US:AMD) had been competing with Intel for a long time without much success, but now seems to have taken a big step up with its product offer. The concern for Intel now is that AMD's chips are much better and considerably cheaper than its own and not just in the PC market. Alphabet's (US:GOOGL) Google is using AMD chips in its cloud data centres, while Microsoft (US:MSFT) and Amazon (US:AMZN) are also using a lot of them these days. Will big PC companies such as Dell and Lenovo do the same? Both Nvidia and AMD just concentrate on chip design and have outsourced production of their chips to Taiwan Semiconductor. This makes sense as they are not in a position to match Intel's scale economies. Instead, they have focused on innovation and making great products, and are having a lot of success Big customers are designing their own chips It seems that there are customers who no longer need Intel. Apple (US:AAPL) has dumped Intel and is designing its own chips to use in its Macbook computers using ARM technology. Amazon is also using ARM. Big customers that would have previously turned to Intel for their chip needs may now choose to design their own using someone else's technology and get TSMC to produce them. Intel should not be written offjust yet Intel is clearly facing a lot of difficulties right now and resembles a wounded giant, but it is far from dead. It still has immense scale and financial strength that can be put to good use. It is developing new artificial intelligence technology for use in areas such as autonomous driving. It also has some good products to sell into 5G mobile networks. The Company's data centre business is performing really well, with revenue growth of 43 per cent in the year to date. However, its PC business, with the exception of notebooks, looks to be ex-growth. The Company is still able to push through price increases in its PC business, which in a different world might be seen as a sign of strength but could now be seen as a bad thing given the growing strength of AMD. Are Intel shares a classic value trap? Intel's problems are very well known. As a result, its shares now look to be extremely cheap compared with its competitors. The Company also still scores very well when looking at key financial performance ratios such as operating margin, return on operating capital employed (ROOCE) and free cash flow margin. For those of you who are familiar with Joel Greenblatt's Magic Formula, which tries to identify businesses with high returns on assets combined with a cheap valuation, then Intel shares - on just over 10 times forecast one-year earnings - look very attractive right now. Intel vs competitors The main drawback with the Magic Formula approach is that it ignores the vital ingredient to achieve good investment returns from owning shares: the ability of a Company to grow. This is where the investment case for Intel seems to fall down at the moment. Intel forecasts With its production problems and fierce competitive backdrop, it looks as though there is very little growth to come from Intel over the next couple of years. Yet the Company is still expected to produce prodigious amounts of free cash flow and arguably doesn't need to grow much to justify its current stock market valuation. However, without some kind of positive newsflow, I struggle to see what drives the shares higher from its current level. There also has to be a real concern that its competitive position continues to weaken. Technology shares have been running hot for a good while now, but Intel is proof that they still have to face up to the same strategic and competitive issues as other businesses. Intel's loss of dominance is also a stark reminder to investors that great businesses need to work hard and smart to stay that way. Owning a share of a business that fails to do this is unlikely to do them much good