Question: please could someone help with this case i. SWOT analysis ii. Other comparative analysis c. Discussion of research findings i. This could include figures, tables,

please could someone help with this case

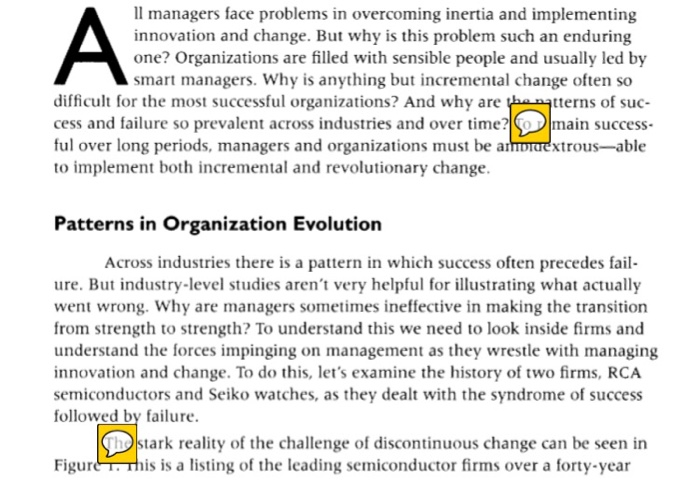

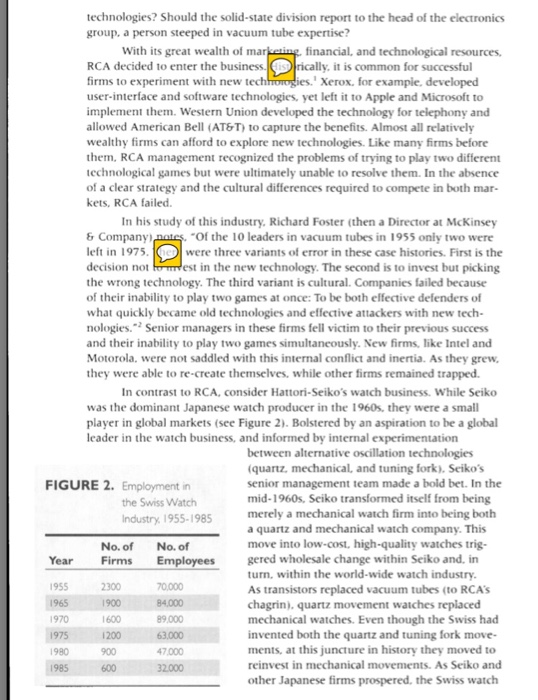

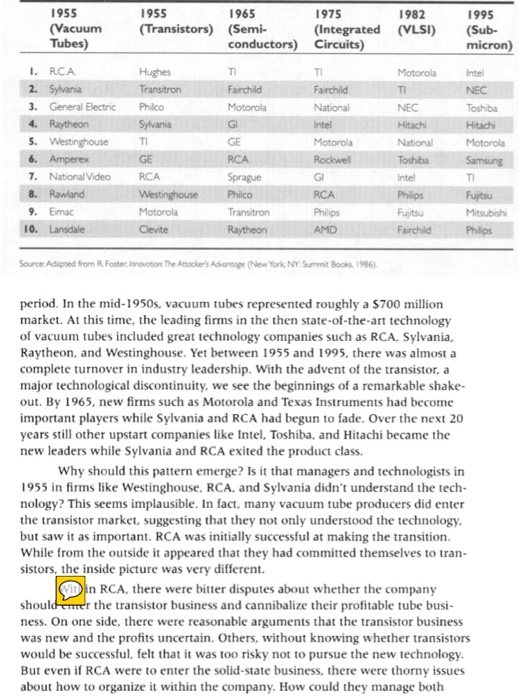

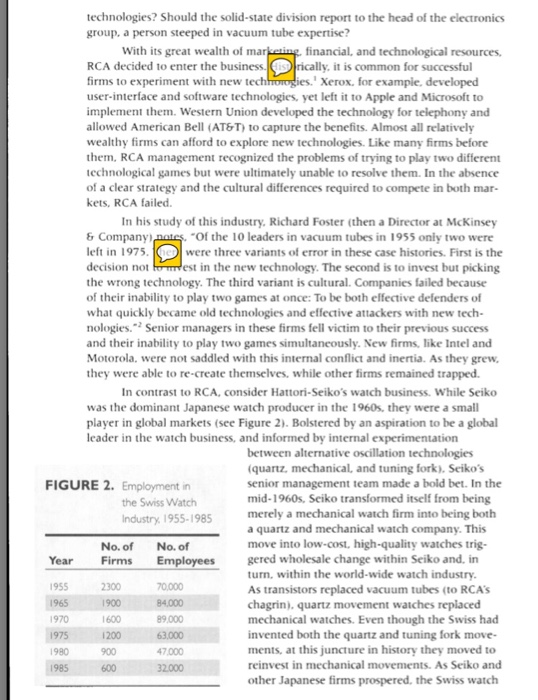

i. SWOT analysis ii. Other comparative analysis c. Discussion of research findings i. This could include figures, tables, etc. 3. Conclusions a. Did you agree with the authors? b. Is the author's viewpoint in line with current thinking? 4. Recommendations a. How could future work in the topic area be improved Il managers face problems in overcoming inertia and implementing innovation and change. But why is this problem such an enduring one? Organizations are filled with sensible people and usually led by smart managers. Why is anything but incremental change often so difficult for the most successful organizations? And why are the matterns of suc- cess and failure so prevalent across industries and over time? Somain success. ful over long periods, managers and organizations must be an ordextrous-able to implement both incremental and revolutionary change. Patterns in Organization Evolution Across industries there is a pattern in which success often precedes fail- ure. But industry-level studies aren't very helpful for illustrating what actually went wrong. Why are managers sometimes ineffective in making the transition from strength to strength? To understand this we need to look inside firms and understand the forces impinging on management as they wrestle with managing innovation and change. To do this, let's examine the history of two firms, RCA semiconductors and Seiko watches, as they dealt with the syndrome of success followed by failure. Sh stark reality of the challenge of discontinuous change can be seen in Figure. This is a listing of the leading semiconductor firms over a forty-year 1955 (Vacuum Tubes) 1955 (Transistors) 1965 (Semi- conductors) 1975 (Integrated Circuits) 1982 (VLSI) 1995 (Sub- micron) Motorola Hughes Transitron Phico Sylvania Fairchild Motorola I. RCA 2. Sylvania 3. General Electric 4. Raytheon 5. Westinghouse 6. Amperex 7. National Video 8. Rawland 9. Eimac 10. Lansdale Fairchild National Intel Motorola Rockwell NEC Toshiba Hitachi Motorola Samsung NEC Hitachi National Toshiba Intel Philips Fujitsu Fairchild RCA Sprague Philco Transitron Raytheon RCA Westinghouse Motorola Cevite RCA Philips AMD Fujitsu Mitsubishi Philips Source: Adapted from R Foster motion The Amer's Advantage (New York, NY: Summit Books, 1986) period. In the mid-1950s, vacuum tubes represented roughly a $700 million market. At this time, the leading firms in the then state-of-the-art technology of vacuum tubes included great technology companies such as RCA, Sylvania, Raytheon, and Westinghouse. Yet between 1955 and 1995, there was almost a complete turnover in industry leadership. With the advent of the transistor, a major technological discontinuity, we see the beginnings of a remarkable shake- out. By 1965, new firms such as Motorola and Texas Instruments had become important players while Sylvania and RCA had begun to fade. Over the next 20 years still other upstart companies like Intel, Toshiba, and Hitachi became the new leaders while Sylvania and RCA exited the product class. Why should this pattern emerge? Is it that managers and technologists in 1955 in firms like Westinghouse, RCA, and Sylvania didn't understand the tech- nology? This seems implausible. In fact, many vacuum tube producers did enter the transistor market, suggesting that they not only understood the technology, but saw it as important. RCA was initially successful at making the transition While from the outside it appeared that they had committed themselves to tran- sistors, the inside picture was very different. ID in RCA, there were bitter disputes about whether the company shoulder the transistor business and cannibalize their profitable tube busi- ness. On one side, there were reasonable arguments that the transistor business was new and the profits uncertain. Others, without knowing whether transistors would be successful, felt that it was too risky not to pursue the new technology But even if RCA were to enter the solid-state business, there were thorny issues about how to organize it within the company. How could they manage both technologies? Should the solid-state division report to the head of the electronics group, a person steeped in vacuum tube expertise? With its great wealth of marketing, financial and technological resources RCA decided to enter the business rically, it is common for successful firms to experiment with new technologies. Xerox, for example, developed user interface and software technologies, yet left it to Apple and Microsoft to implement them. Western Union developed the technology for telephony and allowed American Bell (AT&T) to capture the benefits. Almost all relatively wealthy firms can afford to explore new technologies. Like many firms before them. RCA management recognized the problems of trying to play two different Technological games but were ultimately unable to resolve them. In the absence of a clear strategy and the cultural differences required to compete in both mar- kets, RCA failed In his study of this industry, Richard Foster (then a Director at McKinsey & Company notes. Of the 10 leaders in vacuum tubes in 1955 only two were left in 1975. 10 were three variants of error in these case histories. First is the decision not to rest in the new technology. The second is to invest but picking the wrong technology. The third variant is cultural. Companies failed because of their inability to play two games at once: To be both effective defenders of what quickly became old technologies and effective attackers with new tech- nologies. Senior managers in these firms fell victim to their previous success and their inability to play two games simultaneously. New firms, like Intel and Motorola, were not saddled with this internal conflict and inertia. As they grew, they were able to re-create themselves, while other firms remained trapped. In contrast to RCA, consider Hattori-Seiko's watch business. While Seiko was the dominant Japanese watch producer in the 1960s, they were a small player in global markets (see Figure 2). Bolstered by an aspiration to be a global leader in the watch business, and informed by internal experimentation between alternative oscillation technologies (quartz, mechanical, and tuning fork), Seiko's FIGURE 2. Employment in senior management team made a bold bet. In the the Swiss Watch mid-1960s. Seiko transformed itself from being Industry, 1955-1985 merely a mechanical watch firm into being both a quartz and mechanical watch company. This No. of No. of move into low-cost, high-quality watches trig- Year Firms Employees gered wholesale change within Seiko and, in turn, within the world-wide watch industry. 1955 2300 70.000 As transistors replaced vacuum tubes (to RCA'S 1965 1900 84.000 chagrin), quartz movement watches replaced 1970 1600 89.000 mechanical watches. Even though the Swiss had 1975 63.000 invented both the quartz and tuning fork move- 1980 900 47.000 ments at this juncture in history they moved to 1985 600 32.000 reinvest in mechanical movements. As Seiko and other Japanese firms prospered, the Swiss watch 1200 industry drastically suffered. By 1980. SSIH, the largest Swiss watch firm, was less than half the size of Seiko. Eventually. SSIH and Asuag. the two largest Swiss firms, went bankrupt. It would not be until after these firms were taken over by the Swiss banks and transformed by Nicholas Hayek that the Swiss would move to recapture the watch market. real test of leadership, then, is to be able to compete successfully by both ilking the alignment or fit among strategy. Structure, culture, and proc. esses, while simultaneously preparing for the inevitable revolutions required by discontinuous environmental change. This requires organizational and manage ment skills to compete in a mature market (where cost, efficiency, and incre. mental innovation are key) and to develop new products and services (where radical innovation, speed, and flexibility are critical). A focus on either one of these skill sets is conceptually easy. Unfortunately, focusing on only one guaran- tees short-term success but long-term failure. Managers need to be able to do both at the same time, that is, they need to be ambidextrous. Juggling provides a metaphor. A juggler who is very good at manipulating a single ball is not inter- esting. It is only when the juggler can handle multiple balls at one time that his or her skill is respected e short examples are only two illustrations of the pattern by which orgarlmans evolve: periods of incremental change punctuated by discontinu. ous or revolutionary change. Long-term success is marked by increasing align- ment among strategy, structure, people, and culture through incremental or evolutionary change punctuated by discontinuous or revolutionary change that requires the simultaneous shift in strategy, structure, people, and culture. These discontinuous changes are almost always driven either by organizational perfor mance problems or by major shifts in the organization's environment, such as technological or competitive shifts. Where those less successful firms (eg. SSIH. RCA) react to environmental jolts, those more successful firms proactively initi- ate innovations that reshape their market (e.g.. Seiko). What's Happening? Understanding Patterns of Organizational Evolution These patterns in organization evolution are not unique. Almost all successful organizations evolve through relatively long periods of incremental change punctuated by environmental shifts and revolutionary change. These discontinuities may be driven by technology, competitors, regulatory events, or significant changes in economic and political conditions. For example, deregula tion in the financial services and airline industries led to waves of mergers and failures as firms scrambled to reorient themselves to the new competitive envi- ronment. Major political changes in Eastern Europe and South Africa have had a similar impact. The combination of the European Union and the emergence of global competition in the automobile and electronics industries has shifted the basis of competition in these markets. Technological change in microprocessors has altered the face of the computer industry. The sobering fact is that the clich about the increasing pace of change seems to be true. Sooner or later, discontinuities upset the congruence that has been a part of the organization's success. Unless their competitive environment remains stable-an increasingly unlikely condition in today's world-firms must confront revolutionary change. The underlying cause of this pattern can be found in an unlikely place: evolutionary biology. Innovation Patterns Over Time many years, biological evolutionary theory proposed that the process of addon occurred gradually over long time periods. The process was assumed to be one of variation, selection, and retention. Variations occurred naturally within species across generations. Those variations that were most adapted to the environment would, over time, enable a species to survive and reproduce. This form would be selected in that it endured while less adaptable forms reproduced less productively and would diminish over time. For instance, if the world became colder and snowier, animals who were whiter and had heavier coats would be advantaged and more likely to survive. As climatic changes affected vegetation, those species with longer necks or stronger beaks might do better. In this way, variation led to adaptation and fitness, which was subsequently retained across generations. In this early view, the environment changed gradually and species adapted slowly to these changes. There is ample evidence that this view has validity. But this perspective missed a crucial question: What happened if the environment was characterized, not by gradual change, but periodic discontinu- ities? What about rapid changes in temperature, or dramatic shifts in the avail- ability of food? Under these conditions, a reliance on gradual change was a one-way ticket to extinction. Id of slow change, discontinuities required a different version of Darwinistory-that of punctuated equilibria in which long periods of gradual change were interrupted periodically by massive discon- tinuities. What then? Under these conditions, survival or selection goes to those species with the characteristics needed to exploit the new environment. resses through long periods of incremental change punctuated by brief periods of revolutionary or discontinuous change So it seems to be with organizations. An entire subfield of research on organizations has demonstrated many similarities between populations of insects and animals and populations of organizations. This field, known as organiza- tional ecology, has successfully applied models of population ecology to the study of sets of organizations in areas as diverse as wineries, newspapers, auto- mobiles, biotech companies, and restaurants. The results confirm that popula- tions of organizations are subject to ecological pressures in which they evolve through periods of incremental adaptation punctuated by discontinuities. Varia- tions in organizational strategy and form are more or less suitable for different environmental conditions. Those organizations and managers who are most able to adapt to a given market or competitive environment will prosper. Over time. the fittest survive-until there is a major discontinuity. At that point managers of firms are faced with the challenge of reconstituting their organizations to adjust to the new environment. Managers who try to adapt to discontinuities through incremental adjustment are unlikely to succeed. The processes of varia- tion, selection, and retention that winnow the fittest of animal populations seem to apply to organizations as well. To understand how this dynamic affects organizations, we need to con sider two fundamental ideas: how organizations grow and evolve, and how dis- continuities affect this process. Armed with this understanding, we can then show how managers can cope with evolutionary and revolutionary change. Organizational Growth and Evolution CD is a pattern that describes organizational growth. All organizations evolve Torrowing the familiar S-curve shown in Figure 3. For instance, consider the history of Apple Computer and how it grew. In its inception, Apple was no so much an organization as a small group of people trying to design, produce, and sell a new product, the personal computer. With success, came the begin nings of a formal organization, assigned roles and responsibilities, some rudi. mentary systems for accounting and payroll, and a culture based on the shared expectations among employees about innovation, commitment, and speed. Suc. cess at this stage was seen in terms of congruence among the strategy, structure, people, and culture. Those who fit the Apple values and subscribed to the cul. tural norms stayed. Those who found the Jobs and Wozniak vision too cultish leit. This early structure was aligned with the strategy and the critical tasks needed to implement it. Success flowed not only from having a new product with desirable features, but also from the ability of the organization to design, manufacture, market, and distribute the new PC. The systems in place tracked those outcomes and processes that were important for the implementation of a single product strategy. Congruence among the elements of the organization is a key to high performance across industries As the firm continued its successful growth, several inexorable changes occurred. First, it got larger. As this occurred, more structure and systems were added. Although this trend toward professionalization was resisted by Jobs (who referred to professional managers as "bozos), the new structures and procedures were required for efficiency and control. Without them, chaos would have reigned. As Apple got older, new norms were developed about what was important and acceptable and what would not be tolerated. The culture changed to reflect the new challenges. Success at Apple and at other firms is based on learning what works and what doesn't Inevitably, even Apple's strategy had to change. What used to be a single product firm (selling the Apple PC and then its successor, the Apple Il now sold a broader range of products in increasingly competitive markets. Instead of a evolve, bases of competition shift within the market. As organizations change their strategies, they must also realign their organizations to accomplish the new strategic objectives. This usually requires a revolutionary change. A short illustration from the development of the automobile will help show how dramatic these changes can be for organizations. At the turn of the century, bicycles and horse-driven carriages were threatened by the "horseless carriage, soon to be called the automobile. Early in this new product class there was substantial competition among alternative technologies. For instance, there were several competing alternative energy sources-steam, battery, and internal combustion engines. There were also different steering mechanisms and arrangements for passenger compartments. In a fairly short period of time, how ever, there emerged a consensus that certain features were to be standard that is, a dominant design emerged. This consisted of an internal combustion engine, steering wheel on the left in the U.S.), brake pedal on the right, and dutch on the left this dominant design was epitomized in the Ford Model T). Once this standard emerged, the basis of competition shifted from variations in what an automobile looked like and how it was powered to features and cost. The new competitive arena emphasized lower prices and differentiated market segments. not product Variation. The imperative for managers was to change their strate- gies and organizations to compete in this market. Those that were unable to manage this transition failed. Similar patterns can be seen in almost all product classes (e.g.. computers, telephones, fast foods, retail stores). With a little imagin , it is easy to feel what the managerial challenges are in this environment. Sping aside the pressures of growth and success. managers must continually readjust their strategies and realign their organiza- tions to reflect the underlying dynamics of technological change in their mar. kets. These changes are not driven by fad or fashion but reflect the imperatives of fundamental change in the technology. This dynamic is a powerful cause of punctuated equilibria and can demand revolutionary rather than incremental change. This pattern occurs across industries as diverse as computers and cement, the only issue is the frequency with which these cycles repeat them- selves. Faced with a discontinuity, the option of incremental change is not likely to be viable. The danger is that, facing a discontinuous change, firms that have been successful may suffer from life-threatening inertia-inertia that results from the very congruence that made the firm successful in the first place. The Success Syndrome: Congruence as a Managerial Trap Managers, as architects of their organizations are responsible for designing their units in ways that best fit their strategic challenges. Internal congruence among strategy, structure, culture, and people drives short-term performance. Between 1915 and 1960. General Radio had a strategy of high- quality, high-priced electronic equipment with a loose functional structure, strong internal promotion practices, and engineering dominance in decision making. All these things worked together to provide a highly congruent system and, in turn, a highly successful organization. However, the strategy and organi- zational congruence that made General Radio a success for 50 years became in the face of major competitive and technological change, a recipe for failure in the 1960s. It was only after a revolutionary change that included a new strategy and simultaneous shifts in structure, people, and culture that the new company. renamed Gen Rad, was able to compete again against the likes of Hewlett- Packard and Textronix. Successful companies learn what works well and incorporate this into their operations. This is what organizational learning is about using feedback from the market to continually refine the organization to get better and better at accomplishing its mission. A lack of congruence (or internal inconsistency in strategy, structure, culture, and people) is usually associated with a firm's cur- rent performance problems. Further, since the fit between strategy, structure, people, and processes is never perfect, achieving congruence is an ongoing process requiring continuous improvement and incremental change. With evo- lutionary change managers are able to incrementally alter their organizations. Given that these changes are comparatively small, the incongruence injected by the change is controllable. The process of making incremental changes is well known and the uncertainty created for people affected by such changes is within tolerable limits. The overall system adapts, but it is not transformed. When done effectively, evolutionary change of this sort is a crucial part of short-term success. But there is a dark side to this success. As we described with Apple, success resulted in the company becoming larger and older. Older, larger firms develop structural and cultural inertiathe organizational equivalent of high cholesterol. Figure 5 shows the paradox of success. As companies grow, they develop structures and systems to handle the increased complexity of the work. These structures and systems are interlinked so that proposed changes become more difficult, more costly, and require more time to implement, espe- cially if they are more than small, incremental modifications. This results in structural inertia resistance to change rooted in the size, complexity, and inter- dependence in the organization's structures, systems, procedures, and processes. Quite different and significantly more pervasive than structural inertia is the cultural inertia that comes from age and success. As organizations get older, part of their learning is embedded in the shared expectations about how things are to be done. These are sometimes seen in the informal norms, values. social networks and in myths, stories, and heroes that have evolved over time. The more successful an organization has been the passinstitutionalized or ingrained these norms, values, and lessons become. S hore institutionalized these norms, values, and stories are, the greater the cultural inertia--the greater the organizational complacency and arrogance. In relatively stable environ- ments, the firm's culture is a critical component of its success. Culture is an effective way of controlling and coordinating people without elaborate and changes in technology, regulation, or competition, great managers understand this dynamic and effectively manage both the short-term demands for increasing congruence and bolstering today's culture and the periodic need to transform their organization and re-create their unit's culture. These organizational trans- formations involve fundamental shifts in the firm's structure and systems as well as in its culture and competencies. Where change in structure and systems is relatively simple, change in culture is not. The issue of actively managing orga- nization cultures that can handle both incremental and discontinuous change is perhaps the most demanding aspect in the management of strategic innovation and change. Ambidextrous Organizations: Mastering Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change The dilemma confronting managers and organizations is clear. In the short run they must constantly increase the fit or alignmenol grategy, struc ture, and culture. This is the world of evolutionary change. W his is not enough for sustained success. In the long-run, managers may ve required to destroy the very alignment that has made their organizations successful. For managers, this means operating part of the time in a world characterized by periods of relatively stability and incremental innovation, and part of the time in a world characterized by revolutionary change. These contrasting managerial demands require that managers periodically destroy what has been created in order to reconstruct a new organization better suited for the next wave of com- petition or technology." modextrous organizations are needed if the success paradox is to be overcome the ability to simultaneously pursue both incremental and discontin- uous innovation and change results from hosting multiple contradictory struc tures, processes, and cultures within the same firm. There are good examples of companies and managers who have succeeded in balancing these tensions. To illustrate more concretely how firms can do this, consider three successful ambidextrous organizations, Hewlett-Packard, Johnson & Johnson, and ABB (Asea Brown Boveri). Each of these has been able to compete in mature market segments through incremental innovation and in emerging markets and tech- nologies through discontinuous innovation. Each has been successful at winning by engaging in both evolutionary and revolutionary change. At one level they are very different companies. HP competes in markets like instruments, computers, and networks. J&J is in consumer products, phar- maceuticals, and professional medical products ranging from sutures to endo- scopic surgical equipment. ABB sells power plants, electrical transmission equipment, transportation systems, and environmental controls. Yet each of them has been able to be periodically renew itself and to produce streams of innovation. HP has gone from an instrument company to a minicomputer firm to a personal computer and network company. J&J has moved from consumer

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock