Question: Please do in the MobaXterm 300 CHAPTER 8 THE BOURNE AGAIN SHELL (bash) ; AND NEWLINE SEPARATE COMMANDS The NEWLINE character is a unique control

Please do in the MobaXterm

Please do in the MobaXterm

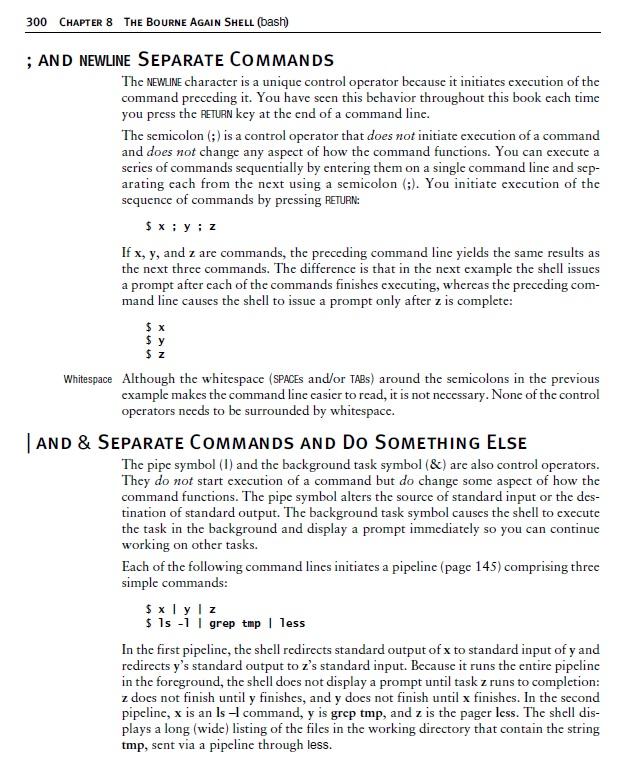

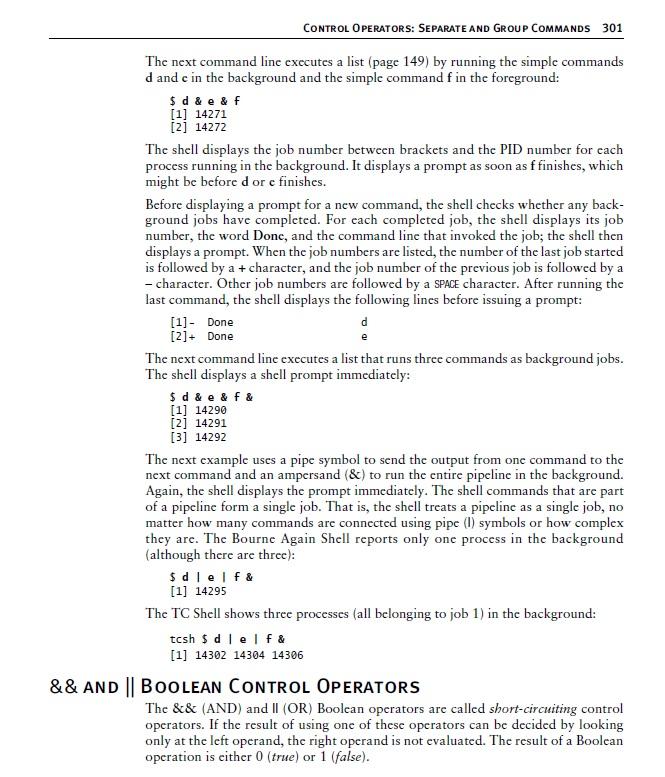

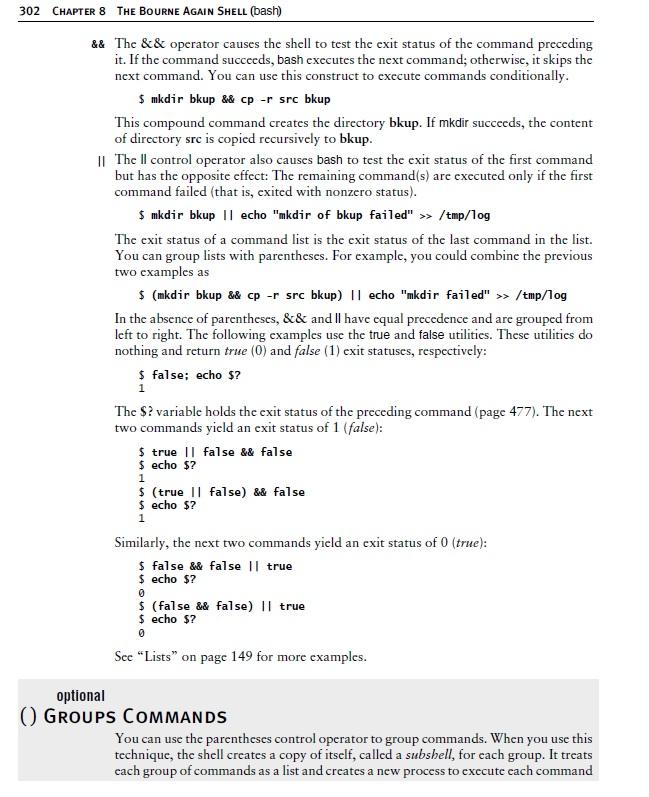

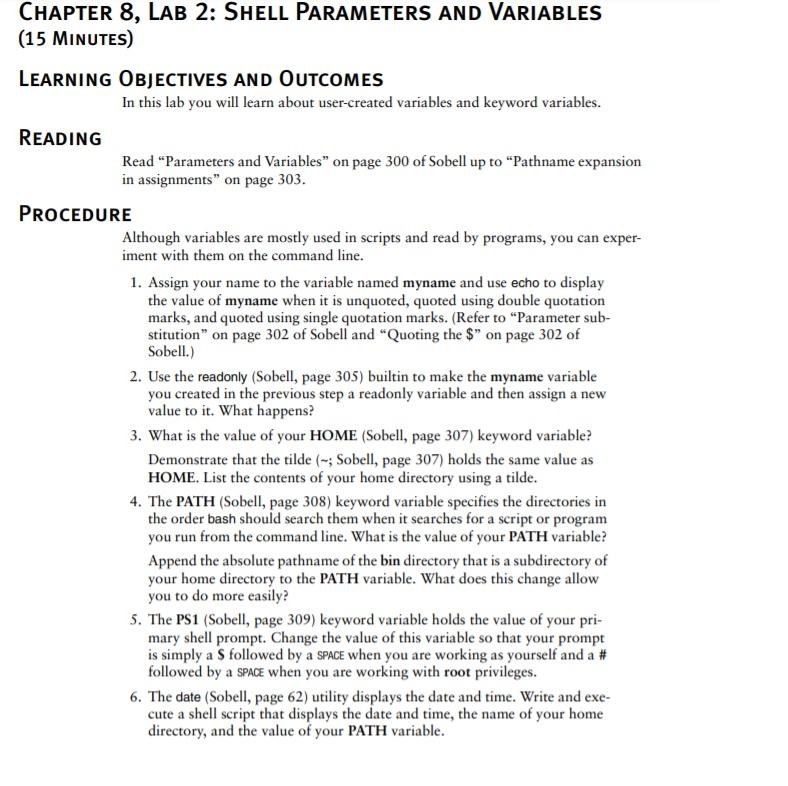

300 CHAPTER 8 THE BOURNE AGAIN SHELL (bash) ; AND NEWLINE SEPARATE COMMANDS The NEWLINE character is a unique control operator because it initiates execution of the command preceding it. You have seen this behavior throughout this book cach time you press the RETURN key at the end of a command line. The semicolon (;) is a control operator that does not initiate execution of a command and does not change any aspect of how the command functions. You can execute a series of commands sequentially by entering them on a single command line and sep- arating each from the next using a semicolon (;). You initiate execution of the sequence of commands by pressing RETURN: $x; y; z If x, y, and z are commands, the preceding command line yields the same results as the next three commands. The difference is that in the next example the shell issues a prompt after each of the commands finishes executing, whereas the preceding com- mand line causes the shell to issue a prompt only after z is complete: $ x $ y $z Whitespace Although the whitespace (SPACES and/or TABs) around the semicolons in the previous example makes the command line casier to read, it is not necessary. None of the control operators needs to be surrounded by whitespace. AND & SEPARATE COMMANDS AND DO SOMETHING ELSE The pipe symbol (1) and the background task symbol (&) are also control operators. They do not start execution of a command but do change some aspect of how the command functions. The pipe symbol alters the source of standard input or the des- tination of standard output. The background task symbol causes the shell to execute the task in the background and display a prompt immediately so you can continue working on other tasks. Each of the following command lines initiates a pipeline (page 145) comprising three simple commands: $ x y z $ ls -1 | grep tmp less In the first pipeline, the shell redirects standard output of x to standard input of y and redirects y's standard output to z's standard input. Because it runs the entire pipeline in the foreground, the shell does not display a prompt until task z runs to completion: z does not finish until y finishes, and y does not finish until x finishes. In the second pipeline, x is an Is command, y is grep tmp, and z is the pager less. The shell dis- plays a long (wide) listing of the files in the working directory that contain the string tmp, sent via a pipeline through less. CONTROL OPERATORS: SEPARATE AND GROUP COMMANDS 301 The next command linc executes a list (page 149) by running the simple commands d and c in the background and the simple command f in the foreground: $ d &e &f [1] 14271 [2] 14272 The shell displays the job number between brackets and the PID number for cach process running in the background. It displays a prompt as soon as f finishes, which might be before d or e finishes. Before displaying a prompt for a new command, the shell checks whether any back- ground jobs have completed. For each completed job, the shell displays its job number, the word Donc, and the command line that invoked the job; the shell then displays a prompt. When the job numbers are listed, the number of the last job started is followed by a + character, and the job number of the previous job is followed by a - character. Other job numbers are followed by a SPACE character. After running the last command, the shell displays the following lines before issuing a prompt: [1] - Done d [2]+ Done The next command line executes a list that runs three commands as background jobs. The shell displays a shell prompt immediately: $ d&e & f& [1] 14290 [2] 14291 [3] 1429 The next example uses a pipe symbol to send the output from one command to the next command and an ampersand (&) to run the entire pipeline in the background. Again, the shell displays the prompt immediately. The shell commands that are part of a pipeline form a single job. That is, the shell treats a pipeline as a single job, no matter how many commands are connected using pipe (1) symbols or how complex they are. The Bourne Again Shell reports only one process in the background (although there are three): $d 1elf & [1] 14295 The TC Shell shows three processes (all belonging to job 1) in the background: tcsh $ d elf & [1] 14302 14304 14306 && AND || BOOLEAN CONTROL OPERATORS Thc && (AND) and II (OR) Boolean operators are called short-circuiting control operators. If the result of using one of these operators can be decided by looking only at the left opcrand, the right opcrand is not evaluated. The result of a Boolean operation is either 0 (true) or 1 (false). 302 CHAPTER 8 THE BOURNE AGAIN SHELL (bash) && The && operator causes the shell to test the exit status of the command preceding it. If the command succeeds, bash executes the next command; otherwise, it skips the next command. You can use this construct to execute commands conditionally. $ mkdir bkup & cp -- src bkup This compound command creates the directory bkup. If mkdir succeeds, the content of directory src is copied recursively to bkup. || The Il control operator also causes bash to test the exit status of the first command but has the opposite effect: The remaining command(s) are executed only if the first command failed (that is, exited with nonzero status). $ mkdir bkup 11 echo "mkdir of bkup failed"> /tmp/log The exit status of a command list is the exit status of the last command in the list. You can group lists with parentheses. For example, you could combine the previous two examples as $(mkdir bkup && cp -- src bkup) || echo "mkdir failed" >> /tmp/log In the absence of parentheses, && and I have equal precedence and are grouped from left to right. The following examples use the true and false utilities. These utilities do nothing and return true (0) and false (1) exit statuses, respectively: $ false; echo $? 1 The $? variable holds the exit status of the preceding command (page 477). The next two commands yield an exit status of 1 (false): $true Il false && false $ echo $? 1 $(true 11 false) && false $ echo $? Similarly, the next two commands yield an exit status of 0 (true): $ false && false 1 true $ echo $? 0 $(false && false) II true $ echo $? 0 Sec "Lists" on page 149 for more examples. optional (GROUPS COMMANDS You can use the parentheses control operator to group commands. When you use this technique, the shell creates a copy of itself, called a subshell, for each group. It treats cach group of commands as a list and creates a new process to execute each command CHAPTER 8, LAB 2: SHELL PARAMETERS AND VARIABLES (15 MINUTES) LEARNING OBJECTIVES AND OUTCOMES In this lab you will learn about user-created variables and keyword variables. READING Read Parameters and Variables on page 300 of Sobell up to Pathname expansion in assignments" on page 303. PROCEDURE Although variables are mostly used in scripts and read by programs, you can exper- iment with them on the command line. 1. Assign your name to the variable named myname and use echo to display the value of myname when it is unquoted, quoted using double quotation marks, and quoted using single quotation marks. (Refer to "Parameter sub- stitution" on page 302 of Sobell and Quoting the $ on page 302 of Sobell.) 2. Use the readonly (Sobell, page 305) builtin to make the myname variable you created in the previous step a readonly variable and then assign a new value to it. What happens? 3. What is the value of your HOME (Sobell, page 307) keyword variable? Demonstrate that the tilde (-; Sobell, page 307) holds the same value as HOME. List the contents of your home directory using a tilde. 4. The PATH (Sobell, page 308) keyword variable specifies the directories in the order bash should search them when it searches for a script or program you run from the command line. What is the value of your PATH variable? Append the absolute pathname of the bin directory that is a subdirectory of your home directory to the PATH variable. What does this change allow you to do more easily? 5. The PS1 (Sobell, page 309) keyword variable holds the value of your pri- mary shell prompt. Change the value of this variable so that your prompt is simply a s followed by a SPACE when you are working as yourself and a # followed by a SPACE when you are working with root privileges. 6. The date (Sobell, page 62) utility displays the date and time. Write and exe- cute a shell script that displays the date and time, the name of your home directory, and the value of your PATH variable. 300 CHAPTER 8 THE BOURNE AGAIN SHELL (bash) ; AND NEWLINE SEPARATE COMMANDS The NEWLINE character is a unique control operator because it initiates execution of the command preceding it. You have seen this behavior throughout this book cach time you press the RETURN key at the end of a command line. The semicolon (;) is a control operator that does not initiate execution of a command and does not change any aspect of how the command functions. You can execute a series of commands sequentially by entering them on a single command line and sep- arating each from the next using a semicolon (;). You initiate execution of the sequence of commands by pressing RETURN: $x; y; z If x, y, and z are commands, the preceding command line yields the same results as the next three commands. The difference is that in the next example the shell issues a prompt after each of the commands finishes executing, whereas the preceding com- mand line causes the shell to issue a prompt only after z is complete: $ x $ y $z Whitespace Although the whitespace (SPACES and/or TABs) around the semicolons in the previous example makes the command line casier to read, it is not necessary. None of the control operators needs to be surrounded by whitespace. AND & SEPARATE COMMANDS AND DO SOMETHING ELSE The pipe symbol (1) and the background task symbol (&) are also control operators. They do not start execution of a command but do change some aspect of how the command functions. The pipe symbol alters the source of standard input or the des- tination of standard output. The background task symbol causes the shell to execute the task in the background and display a prompt immediately so you can continue working on other tasks. Each of the following command lines initiates a pipeline (page 145) comprising three simple commands: $ x y z $ ls -1 | grep tmp less In the first pipeline, the shell redirects standard output of x to standard input of y and redirects y's standard output to z's standard input. Because it runs the entire pipeline in the foreground, the shell does not display a prompt until task z runs to completion: z does not finish until y finishes, and y does not finish until x finishes. In the second pipeline, x is an Is command, y is grep tmp, and z is the pager less. The shell dis- plays a long (wide) listing of the files in the working directory that contain the string tmp, sent via a pipeline through less. CONTROL OPERATORS: SEPARATE AND GROUP COMMANDS 301 The next command linc executes a list (page 149) by running the simple commands d and c in the background and the simple command f in the foreground: $ d &e &f [1] 14271 [2] 14272 The shell displays the job number between brackets and the PID number for cach process running in the background. It displays a prompt as soon as f finishes, which might be before d or e finishes. Before displaying a prompt for a new command, the shell checks whether any back- ground jobs have completed. For each completed job, the shell displays its job number, the word Donc, and the command line that invoked the job; the shell then displays a prompt. When the job numbers are listed, the number of the last job started is followed by a + character, and the job number of the previous job is followed by a - character. Other job numbers are followed by a SPACE character. After running the last command, the shell displays the following lines before issuing a prompt: [1] - Done d [2]+ Done The next command line executes a list that runs three commands as background jobs. The shell displays a shell prompt immediately: $ d&e & f& [1] 14290 [2] 14291 [3] 1429 The next example uses a pipe symbol to send the output from one command to the next command and an ampersand (&) to run the entire pipeline in the background. Again, the shell displays the prompt immediately. The shell commands that are part of a pipeline form a single job. That is, the shell treats a pipeline as a single job, no matter how many commands are connected using pipe (1) symbols or how complex they are. The Bourne Again Shell reports only one process in the background (although there are three): $d 1elf & [1] 14295 The TC Shell shows three processes (all belonging to job 1) in the background: tcsh $ d elf & [1] 14302 14304 14306 && AND || BOOLEAN CONTROL OPERATORS Thc && (AND) and II (OR) Boolean operators are called short-circuiting control operators. If the result of using one of these operators can be decided by looking only at the left opcrand, the right opcrand is not evaluated. The result of a Boolean operation is either 0 (true) or 1 (false). 302 CHAPTER 8 THE BOURNE AGAIN SHELL (bash) && The && operator causes the shell to test the exit status of the command preceding it. If the command succeeds, bash executes the next command; otherwise, it skips the next command. You can use this construct to execute commands conditionally. $ mkdir bkup & cp -- src bkup This compound command creates the directory bkup. If mkdir succeeds, the content of directory src is copied recursively to bkup. || The Il control operator also causes bash to test the exit status of the first command but has the opposite effect: The remaining command(s) are executed only if the first command failed (that is, exited with nonzero status). $ mkdir bkup 11 echo "mkdir of bkup failed"> /tmp/log The exit status of a command list is the exit status of the last command in the list. You can group lists with parentheses. For example, you could combine the previous two examples as $(mkdir bkup && cp -- src bkup) || echo "mkdir failed" >> /tmp/log In the absence of parentheses, && and I have equal precedence and are grouped from left to right. The following examples use the true and false utilities. These utilities do nothing and return true (0) and false (1) exit statuses, respectively: $ false; echo $? 1 The $? variable holds the exit status of the preceding command (page 477). The next two commands yield an exit status of 1 (false): $true Il false && false $ echo $? 1 $(true 11 false) && false $ echo $? Similarly, the next two commands yield an exit status of 0 (true): $ false && false 1 true $ echo $? 0 $(false && false) II true $ echo $? 0 Sec "Lists" on page 149 for more examples. optional (GROUPS COMMANDS You can use the parentheses control operator to group commands. When you use this technique, the shell creates a copy of itself, called a subshell, for each group. It treats cach group of commands as a list and creates a new process to execute each command CHAPTER 8, LAB 2: SHELL PARAMETERS AND VARIABLES (15 MINUTES) LEARNING OBJECTIVES AND OUTCOMES In this lab you will learn about user-created variables and keyword variables. READING Read Parameters and Variables on page 300 of Sobell up to Pathname expansion in assignments" on page 303. PROCEDURE Although variables are mostly used in scripts and read by programs, you can exper- iment with them on the command line. 1. Assign your name to the variable named myname and use echo to display the value of myname when it is unquoted, quoted using double quotation marks, and quoted using single quotation marks. (Refer to "Parameter sub- stitution" on page 302 of Sobell and Quoting the $ on page 302 of Sobell.) 2. Use the readonly (Sobell, page 305) builtin to make the myname variable you created in the previous step a readonly variable and then assign a new value to it. What happens? 3. What is the value of your HOME (Sobell, page 307) keyword variable? Demonstrate that the tilde (-; Sobell, page 307) holds the same value as HOME. List the contents of your home directory using a tilde. 4. The PATH (Sobell, page 308) keyword variable specifies the directories in the order bash should search them when it searches for a script or program you run from the command line. What is the value of your PATH variable? Append the absolute pathname of the bin directory that is a subdirectory of your home directory to the PATH variable. What does this change allow you to do more easily? 5. The PS1 (Sobell, page 309) keyword variable holds the value of your pri- mary shell prompt. Change the value of this variable so that your prompt is simply a s followed by a SPACE when you are working as yourself and a # followed by a SPACE when you are working with root privileges. 6. The date (Sobell, page 62) utility displays the date and time. Write and exe- cute a shell script that displays the date and time, the name of your home directory, and the value of your PATH variable

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts