Please fully answer the following questions about the case in your report:

- Summarize and discuss the core issue in the case. Do not repeat the entire case details but only pertinent information at the heart of the case.

- Identify any ethical and/or moral dilemmas in the case. What is an ethical decision-making? What ethical perspective can be used to analyze this case?

- A firm's suppliers is one of its most important external stakeholders. In light of this case, how do you evaluate the performance of Nike and Walmart when it comes to their relationship with foreign suppliers? Are they doing enough in ensuring compliance and supporting these suppliers' growth? If not, what do you think is missing?

- Recent research in corporate social responsibility (CSR) suggests that we evaluate the firm's performance from three important dimensions:economic, social and environmental. These are commonly referred to as the "Triple Bottom Line". Evaluate Walmart & Nike's economic performance by specifically focusing on their Return on Assets (ROA), Return on Equity (ROE) and growth of stock price from 2012-2016. [Hint: Use Library's Mergent Online database for financial information]. Put charts in appendix of your report and refer to them in the body.

- Similarly, evaluate Nike's & Walmart's environmental (sustainable) performance. Begin by downloading these companies' recent Sustainability Reports from their websites (or related sources). Summarize major initiatives they have that support environmental sustainability in recent years.

- Some analysts express concern that firms sometimes do not fully commit to sustainability as they claim in their official reports ("greenwashing" phenomenon). In your opinion, are these two companies fully committed to addressing environmental issues/concerns? Support your arguments with research

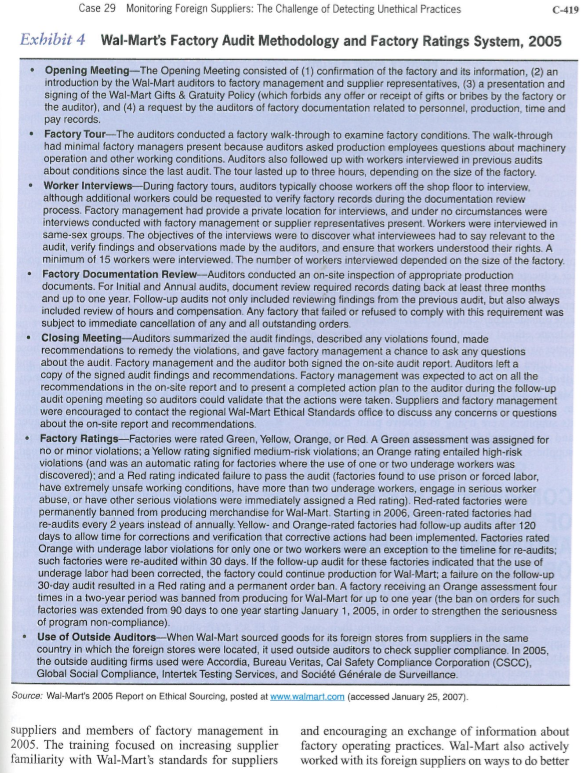

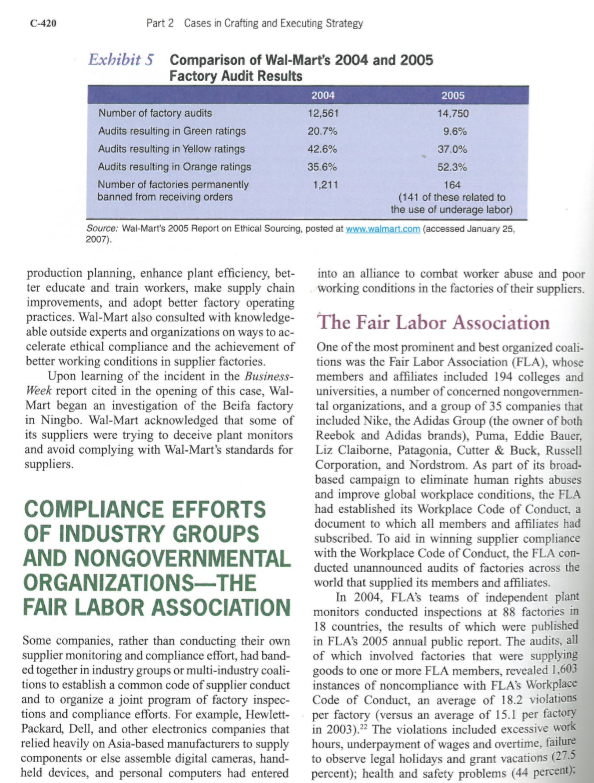

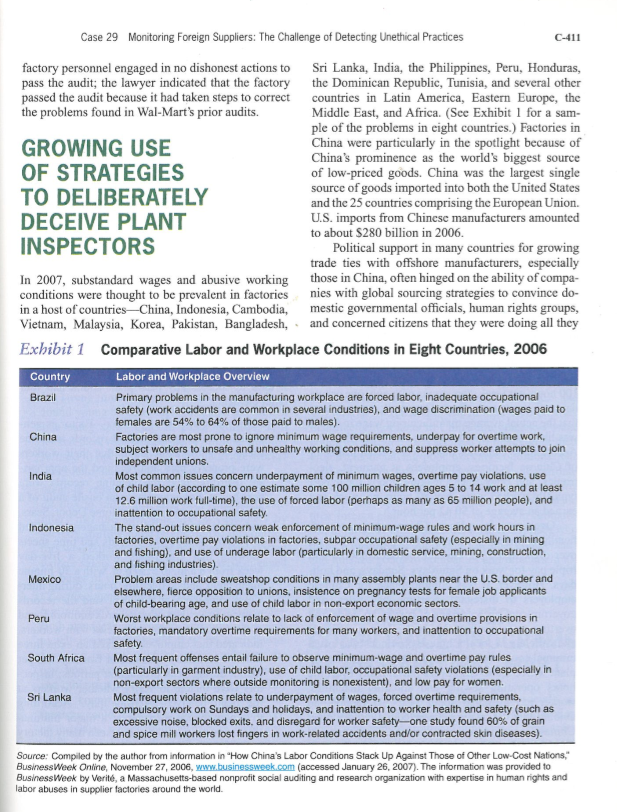

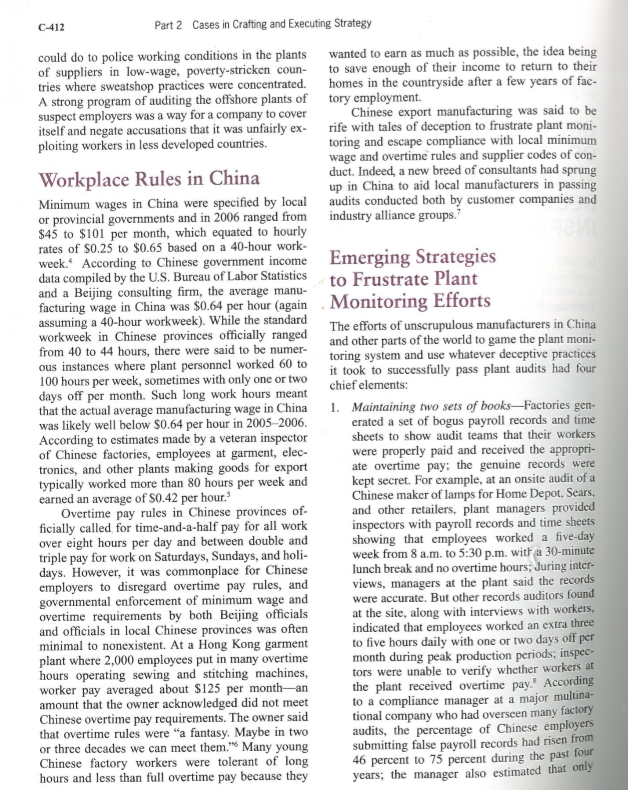

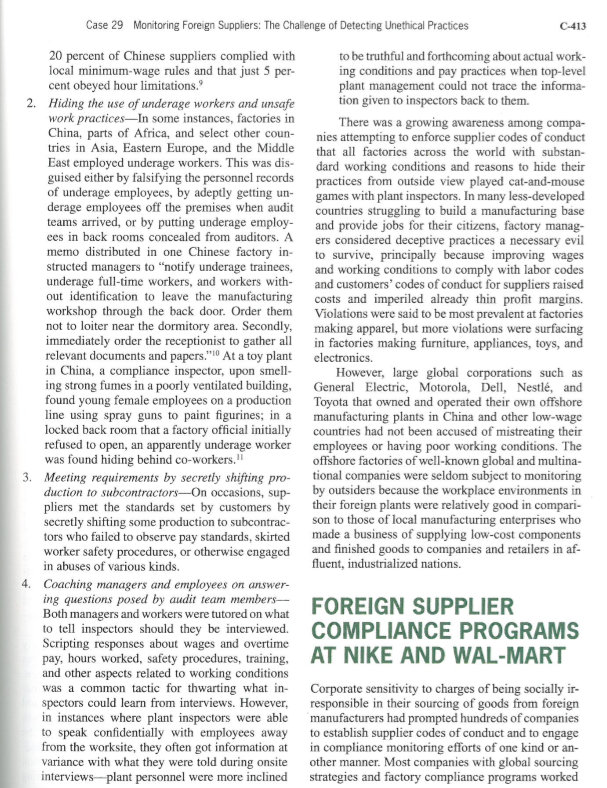

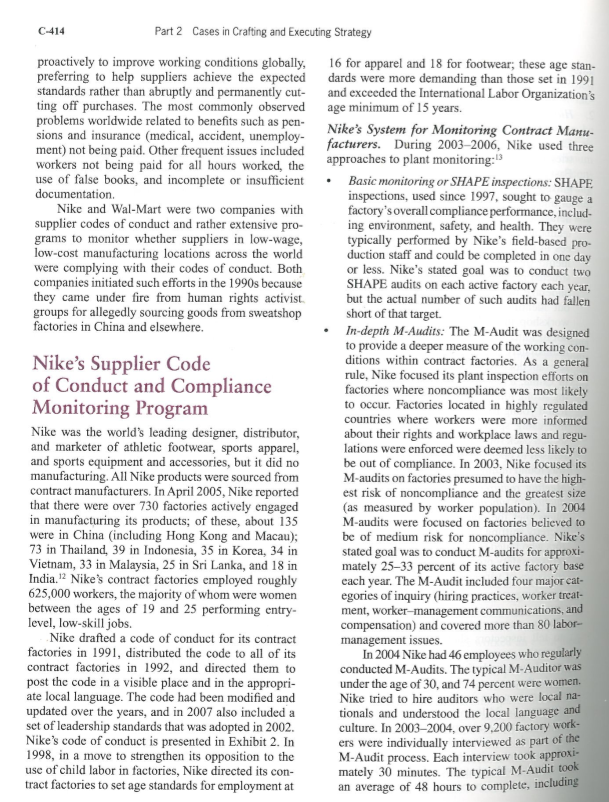

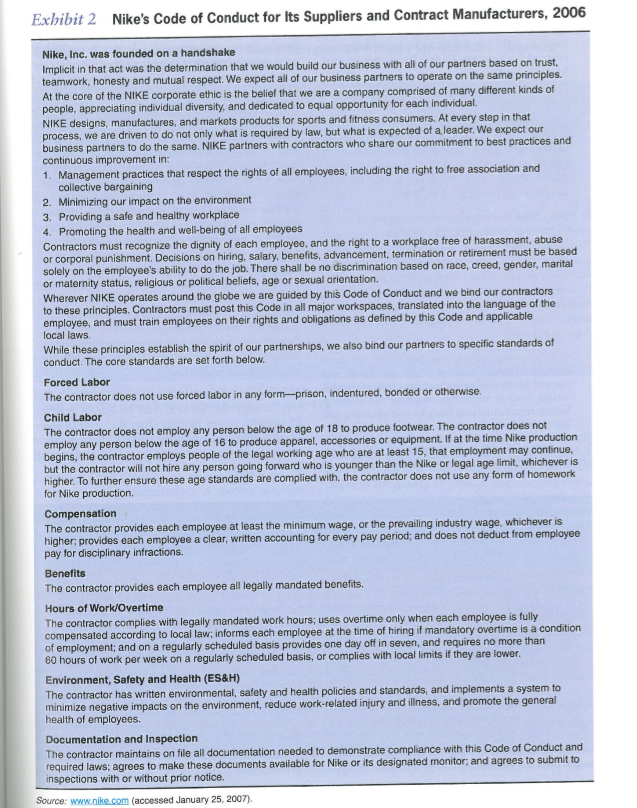

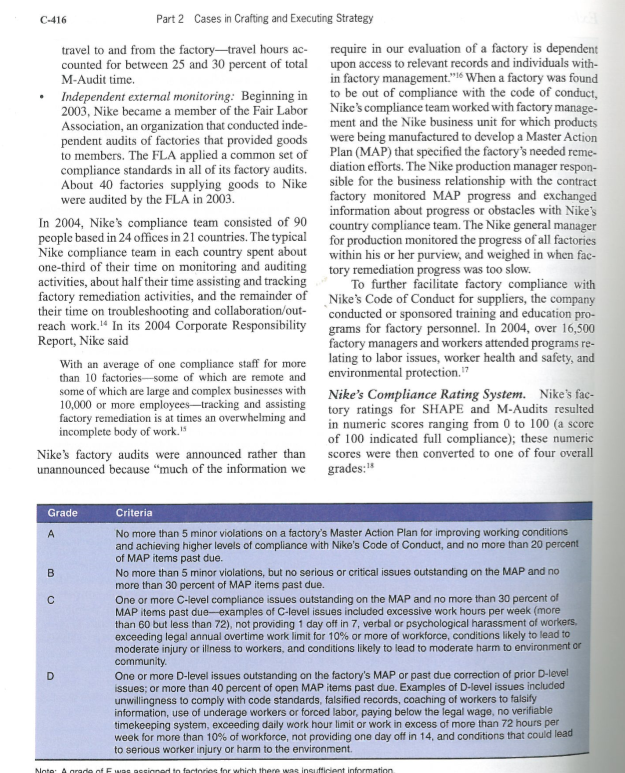

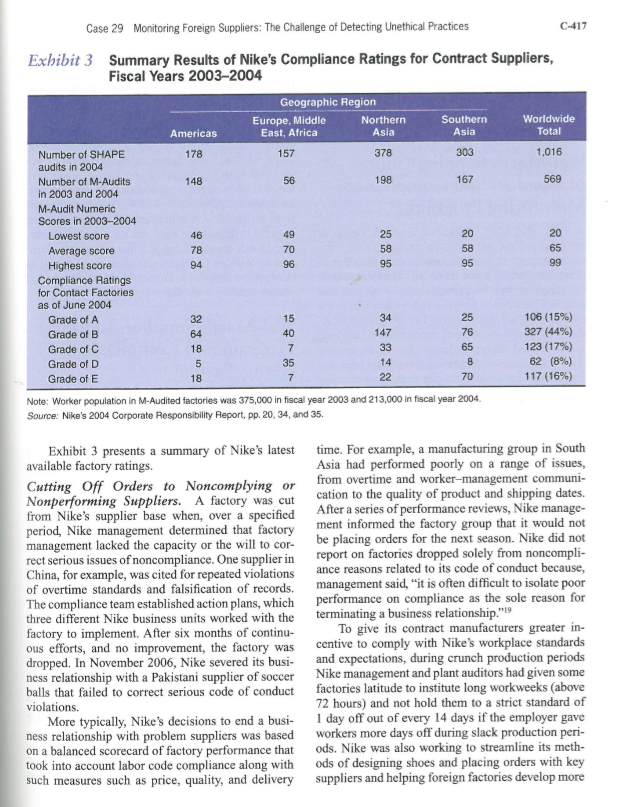

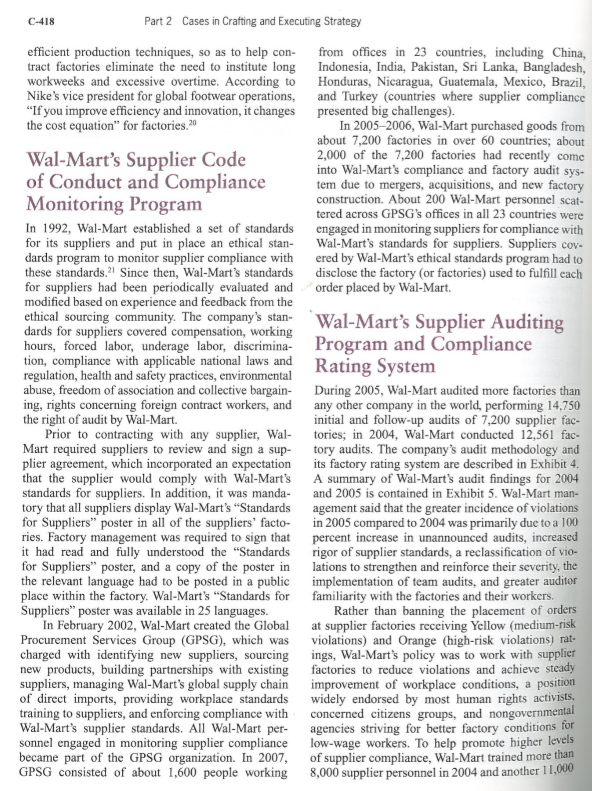

Case Monitoring Foreign Suppliers: The Challenge of Detecting Unethical Practices Arthur A. Thompson The University of Alabama mporters of goods from China, Indonesia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Korea, Pakis- conditions. In November 2006, Business Week ran a L tan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, India, the Philippines, cover story detailing how shady foreign manufacture Peru, Honduras, the Dominican Republic, Tunisia, ers were deceiving inspection teams and escaping and other less developed countries had long had to detection.' According to the Business Week special contend with accusations by human rights activists report, Ningbo Beifa Group-a top Chinese supplier that they sourced goods from sweatshop manufacture of pens, mechanical pens, and highlighters to Wal- ers that paid substandard wages, required unusually Mart, Staples, Woolworth, and some 400 other retail- long work hours, used child labor, operated unsafe ers in 100 countries-was alerted in late 2005 that workplaces, and habitually engaged in assorted other a Wal-Mart inspection team would soon be visiting unsavory practices. Since the 1990s, companies had the company's factory in the coastal city of Ningbo. responded to criticisms about sourcing goods from Wal-Mart was Beifa's largest customer and on three manufacturers in developing nations where work- previous occasions had caught Beija paying its 3,000 ing conditions were often substandard by instituting workers less than the Chinese minimum wage and elaborate codes of conduct for foreign suppliers and violating overtime rules; a fourth offense would end by periodically inspecting the manufacturing facili- Wal-Mart's purchases from Beifa. But weeks prior ties of these suppliers to try to eliminate abuses and to the audit, an administrator at Beifa's factory in promote improved working conditions. In several Ningbo got a call from representatives of Shanghai industries where companies sourced goods from Corporate Responsibility Management & Consulting common foreign suppliers, companies had joined Company offering to help the Beifa factory pass the forces to conduct plant monitoring; for example, Wal-Mart inspection. The Beifa administrator agreed Hewlett-packard, Dell, and other electronics compa- to pay the requested fee of $5,000. The consultant nies that relied heavily on Asia-based manufacturers advised management at the Beifa factory in Ningbo to supply components or assemble digital cameras, to create fake but authentic-looking records regard- handheld devices, and PCs had entered into an alli- ing pay scales and overtime work and make sure to ance to combat worker abuse and poor working con- get any workers with grievances out of the plant on ditions in supplier factories. the day of the audit. Beifa managers at the factory But a number of unscrupulous foreign manu- were also coached on how to answer questions that facturers had recently gotten much better at conceal- the auditors would likely ask. Beifa's Ningbo factory ing human rights abuses and substandard working reportedly passed the Wal-Mart inspection in carly 2006 without altering any of its practices.' A law- yer for Beifa confirmed that the company had indeed Copyright @ 2007 by Arthur A. Thompson. All rights reserved employed the Shanghai consulting firm but said that C-410Case 29 Monitoring Foreign Suppliers: The Challenge of Detecting Unethical Practices C-419 Exhibit 4 Wal-Mart's Factory Audit Methodology and Factory Ratings System, 2005 Opening Meeting-The Opening Meeting consisted of (1) confirmation of the factory and its information, (2) an introduction by the Wal-Mart auditors to factory management and supplier representatives, (3) a presentation and signing of the Wal-Mart Gifts & Gratuity Policy (which forbids any offer or receipt of gifts or bribes by the factory or the auditor), and (4) a request by the auditors of factory documentation related to personnel, production, time and pay records. Factory Tour-The auditors conducted a factory walk-through to examine factory conditions. The walk-through had minimal factory managers present because auditors asked production employees questions about machinery operation and other working conditions. Auditors also followed up with workers interviewed in previous audits about conditions since the last audit. The tour lasted up to three hours, depending on the size of the factory. Worker Interviews-During factory tours, auditors typically choose workers off the shop floor to interview. although additional workers could be requested to verify factory records during the documentation review process. Factory management had provide a private location for interviews, and under no circumstances were interviews conducted with factory management or supplier representatives present. Workers were interviewed in same-sex groups. The objectives of the interviews were to discover what interviewees had to say relevant to the audit, verify findings and observations made by the auditors, and ensure that workers understood their rights. A minimum of 15 workers were interviewed. The number of workers interviewed depended on the size of the factory. Factory Documentation Review-Auditors conducted an on-site inspection of appropriate production documents. For Initial and Annual audits, document review required records dating back at least three months and up to one year, Follow-up audits not only included reviewing findings from the previous audit, but also always included review of hours and compensation. Any factory that failed or refused to comply with this requirement was subject to immediate cancellation of any and all outstanding orders. Closing Meeting-Auditors summarized the audit findings, described any violations found, made recommendations to remedy the violations, and gave factory management a chance to ask any questions about the audit. Factory management and the auditor both signed the on-site audit report. Auditors left a copy of the signed audit findings and recommendations. Factory management was expected to act on all the recommendations in the on-site report and to present a completed action plan to the auditor during the follow-up audit opening meeting so auditors could validate that the actions were taken. Suppliers and factory management were encouraged to contact the regional Wal-Mart Ethical Standards office to discuss any concerns or questions about the on-site report and recommendations. Factory Ratings-Factories were rated Green, Yellow, Orange, or Red. A Green assessment was assigned for no or minor violations; a Yellow rating signified medium-risk violations; an Orange rating entailed high-risk violations (and was an automatic rating for factories where the use of one or two underage workers was discovered); and a Red rating indicated failure to pass the audit (factories found to use prison or forced labor, have extremely unsafe working conditions, have more than two underage workers, engage in serious worker abuse, or have other serious violations were immediately assigned a Red rating). Red-rated factories were permanently banned from producing merchandise for Wal-Mart. Starting in 2006, Green-rated factories had re-audits every 2 years instead of annually. Yellow- and Orange-rated factories had follow-up audits after 120 days to allow time for corrections and verification that corrective actions had been implemented, Factories rated Orange with underage labor violations for only one or two workers were an exception to the timeline for re-audits; such factories were re-audited within 30 days. If the follow-up audit for these factories indicated that the use of underage labor had been corrected, the factory could continue production for Wal-Mart; a failure on the follow-up 30-day audit resulted in a Red rating and a permanent order ban. A factory receiving an Orange assessment four times in a two-year period was banned from producing for Wal-Mart for up to one year (the ban on orders for such factories was extended from 90 days to one year starting January 1, 2005, in order to strengthen the seriousness of program non-compliance) Use of Outside Auditors-When Wal-Mart sourced goods for its foreign stores from suppliers in the same country in which the foreign stores were located, it used outside auditors to check supplier compliance. In 2005, the outside auditing firms used were Accordia, Bureau Veritas, Cal Safety Compliance Corporation (CSCC), Global Social Compliance, Intertek Testing Services, and Societe Generale de Surveillance. Source: Wal-Mart's 2005 Report on Ethical Sourcing, posted at www.walmart.com (accessed January 25, 2007). suppliers and members of factory management in and encouraging an exchange of information about 2005. The training focused on increasing supplier factory operating practices. Wal-Mart also actively familiarity with Wal-Mart's standards for suppliers worked with its foreign suppliers on ways to do betterC-420 Part 2 Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy Exhibit 5 Comparison of Wal-Mart's 2004 and 2005 Factory Audit Results 2004 2005 Number of factory audits 12,561 14.750 Audits resulting in Green ratings 20.7% 9.6% Audits resulting in Yellow ratings 42.6% 37.0% Audits resulting in Orange ratings 35.6% 52.3% Number of factories permanently 1,211 164 banned from receiving orders (141 of these related to the use of underage labor) Source: Wal-Mart's 2005 Report on Ethical Sourcing, posted at www.walmart.com (accessed January 25, 2007). production planning, enhance plant efficiency, bet- into an alliance to combat worker abuse and poor ter educate and train workers, make supply chain working conditions in the factories of their suppliers. improvements, and adopt better factory operating practices. Wal-Mart also consulted with knowledge- able outside experts and organizations on ways to ac- The Fair Labor Association celerate ethical compliance and the achievement of better working conditions in supplier factories. One of the most prominent and best organized coali- tions was the Fair Labor Association (FLA), whose Upon learning of the incident in the Business- members and affiliates included 194 colleges and Week report cited in the opening of this case, Wal- Mart began an investigation of the Beifa factory universities, a number of concerned nongovernmen tal organizations, and a group of 35 companies that in Ningbo. Wal-Mart acknowledged that some of included Nike, the Adidas Group (the owner of both its suppliers were trying to deceive plant monitors Reebok and Adidas brands), Puma, Eddie Bauer, and avoid complying with Wal-Mart's standards for Liz Claiborne, Patagonia, Cutter & Buck, Russell suppliers. Corporation, and Nordstrom. As part of its broad- based campaign to eliminate human rights abuses COMPLIANCE EFFORTS and improve global workplace conditions, the FLA had established its Workplace Code of Conduct, a OF INDUSTRY GROUPS document to which all members and affiliates had subscribed. To aid in winning supplier compliance AND NONGOVERNMENTAL with the Workplace Code of Conduct, the FLA con- ORGANIZATIONS-THE ducted unannounced audits of factories across the world that supplied its members and affiliates. FAIR LABOR ASSOCIATION In 2004, FLA's teams of independent plant monitors conducted inspections at 88 factories in 18 countries, the results of which were published Some companies, rather than conducting their own in FLA's 2005 annual public report. The audits, all supplier monitoring and compliance effort, had band- of which involved factories that were supplying ed together in industry groups or multi-industry coali- goods to one or more FLA members, revealed 1,603 tions to establish a common code of supplier conduct instances of noncompliance with FLA's Workplace and to organize a joint program of factory inspec- Code of Conduct, an average of 18.2 violations tions and compliance efforts. For example, Hewlett- per factory (versus an average of 15.1 per factory Packard, Dell, and other electronics companies that in 2003)." The violations included excessive work relied heavily on Asia-based manufacturers to supply hours, underpayment of wages and overtime, failure components or else assemble digital cameras, hand- to observe legal holidays and grant vacations (27.5 held devices, and personal computers had entered percent); health and safety problems (44 percent);Case 29 Monitoring Foreign Suppliers: The Challenge of Detecting Unethical Practices C-421 and worker harassment (5.1 percent). The FLA con- from as little as $5,000 to as much as $75,000 cluded that the actual violations relating to under- (not including one-time initiation fees of $2,500 payment of wages, hours of work, and overtime to $11,500). The idea underlying the FFC was that compensation were probably higher than those dis- members would pool their audit information on off- covered because "factory personnel have become shore factories, creating a database on thousands of sophisticated in concealing noncompliance relating manufacturing plants. Once a plant was certified by to wages. They often hide original documents and a member company or organization, other members show monitors falsified books."23 In its 2006 public report, the FLA said that ac- could accept the results without having to do an audit of their own. credited independent monitors conducted unan- nounced audits of 99 factories in 18 countries in Audit sharing had the appeal of making factory 2005; the audited factories employed some 77,800 audit programs less expensive for member compa- nies; perhaps more important, it helped reduce the workers." The audited factories were but a small audit burden at plants having large number of cus- sample of the 3,753 factories employing some 2.9 tomers that conducted their own audits. Some large million people from which the FLA's 35 affiliated plants with big customer bases were said to undergo companies sourced goods in 2005; however, 34 of audits as often as weekly and occasionally even daily; the 99 audited factories involved facilities providing plus, they were pressured into having to comply with goods to 2 or more of FLA's 35 affiliated companies. varying provisions and requirements of each audit- The 99 audits during 2005 revealed 1,587 violations, ing company's code of supplier conduct-being an average of 15.9 per audit. The greatest incidence subject to varying and conflicting codes of conduct of violations was found in Southeast Asia (chiefly was a factor that induced cheating. Another benefit factories located in China, Indonesia, Thailand, and of audit sharing at FFC was that members sourcing India), where the average was about 22 violations goods from the same factories could band together per factory audit. As was the case with the audits and apply added pressure on a supplier to improve its conducted in 2004, most of the violations related to working conditions and comply with buyers' codes health and safety (45 percent); wages, benefits, hours of supplier conduct.26 of work, and overtime compensation (28 percent); and worker harassment and abuse (7 percent). Once again, the FLA indicated that the violations relat- THE OBSTACLES TO ing to compensation and benefits were likely higher than those detected in its 2005 audits because "fac- ACHIEVING SUPPLIER tory personnel have become accustomed to conceal- COMPLIANCE WITH ing real wage documentation and providing falsified records at the time of compliance audits, making any CODES OF CONDUCT noncompliances difficult to detect."2 IN LOW-WAGE, LOW-COST The Fair Factories COUNTRIES Clearinghouse Factory managers subject to inspections and audits The Fair Factories Clearinghouse (FFC)-formed of their plants and work practices complained that strong pressures from their customers to keep prices in 2006 by World Monitors Inc. in partnership with low gave them a big incentive to cheat on their com- L. L. Bean, Timberland, Federated Department Stores, pliance with labor standards. As the general manager Adidas/Reebok, the Retail Council of Canada, and of a factory in China that supplied goods to Nike said, several others-was a collaborative effort to create a "Any improvement you make costs more money. The system for managing and sharing factory audit infor- price [ Nike pays] never increases one penny but com- mation that would facilitate detecting and eliminate pliance with labor codes definitely raises costs."?7 ing sweatshops and abusive workplace conditions in The pricing pressures from companies sourcing foreign factories; membership fees were based on a components or finished goods from offshore facto- company's annual revenues, with annual fees ranging ries in China, India, and other low-wage, low-costCase 29 Monitoring Foreign Suppliers: The Challenge of Detecting Unethical Practices C-411 factory personnel engaged in no dishonest actions to Sri Lanka, India, the Philippines, Peru, Honduras, pass the audit; the lawyer indicated that the factory the Dominican Republic, Tunisia, and several other passed the audit because it had taken steps to correct the problems found in Wal-Mart's prior audits. countries in Latin America, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. (See Exhibit I for a sam- ple of the problems in eight countries.) Factories in GROWING USE China were particularly in the spotlight because of OF STRATEGIES China's prominence as the world's biggest source of low-priced goods. China was the largest single TO DELIBERATELY source of goods imported into both the United States DECEIVE PLANT and the 25 countries comprising the European Union. U.S. imports from Chinese manufacturers amounted INSPECTORS to about $280 billion in 2006. Political support in many countries for growing trade ties with offshore manufacturers, especially In 2007, substandard wages and abusive working those in China, often hinged on the ability of compa- conditions were thought to be prevalent in factories nies with global sourcing strategies to convince do- in a host of countries-China, Indonesia, Cambodia, mestic governmental officials, human rights groups, Vietnam, Malaysia, Korea, Pakistan, Bangladesh, . and concerned citizens that they were doing all they Exhibit 1 Comparative Labor and Workplace Conditions in Eight Countries, 2006 Country Labor and Workplace Overview Brazil Primary problems in the manufacturing workplace are forced labor, inadequate occupational safety (work accidents are common in several industries), and wage discrimination (wages paid to females are 54% to 64% of those paid to males). China Factories are most prone to ignore minimum wage requirements, underpay for overtime work, subject workers to unsafe and unhealthy working conditions, and suppress worker attempts to join Independent unions. India Most common issues concern underpayment of minimum wages, overtime pay violations, use of child labor (according to one estimate some 100 million children ages 5 to 14 work and at least 12.6 million work full-time), the use of forced labor (perhaps as many as 65 million people), and inattention to occupational safety. Indonesia The stand-out issues concern weak enforcement of minimum-wage rules and work hours in factories, overtime pay violations in factories, subpar occupational safety (especially in mining and fishing), and use of underage labor (particularly in domestic service, mining, construction, and fishing industries). Mexico Problem areas include sweatshop conditions in many assembly plants near the U.S. border and elsewhere, fierce opposition to unions, insistence on pregnancy tests for female job applicants of child-bearing age, and use of child labor in non-export economic sectors. Peru Worst workplace conditions relate to lack of enforcement of wage and overtime provisions in factories, mandatory overtime requirements for many workers, and inattention to occupational safety. South Africa Most frequent offenses entail failure to observe minimum-wage and overtime pay rules particularly in garment industry), use of child labor, occupational safety violations (especially in non-export sectors where outside monitoring is nonexistent), and low pay for women. Sri Lanka Most frequent violations relate to underpayment of wages, forced overtime requirements, compulsory work on Sundays and holidays, and inattention to worker health and safety (such as excessive noise, blocked exits. and disregard for worker safety-one study found 60% of grain and spice mill workers lost fingers in work-related accidents and/or contracted skin diseases). Source: Compiled by the author from information in "How China's Labor Conditions Stack Up Against Those of Other Low-Cost Nations," BusinessWeek Online, November 27, 2006, www.businessweek.com (accessed January 26, 2007). The information was provided to Business Week by Verite, a Massachusetts-based nonprofit social auditing and research organization with expertise in human rights and labor abuses in supplier factories around the world.C-412 Part 2 Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy could do to police working conditions in the plants wanted to earn as much as possible, the idea being of suppliers in low-wage, poverty-stricken coun- to save enough of their income to return to their tries where sweatshop practices were concentrated. homes in the countryside after a few years of fac- A strong program of auditing the offshore plants of tory employment. suspect employers was a way for a company to cover Chinese export manufacturing was said to be itself and negate accusations that it was unfairly ex- rife with tales of deception to frustrate plant moni- ploiting workers in less developed countries. toring and escape compliance with local minimum wage and overtime rules and supplier codes of con- Workplace Rules in China duct. Indeed, a new breed of consultants had sprung Minimum wages in China were specified by local up in China to aid local manufacturers in passing audits conducted both by customer companies and or provincial governments and in 2006 ranged from industry alliance groups." $45 to $101 per month, which equated to hourly rates of $0.25 to $0.65 based on a 40-hour work- week." According to Chinese government income data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Emerging Strategies and a Beijing consulting firm, the average manu- to Frustrate Plant facturing wage in China was $0.64 per hour (again assuming a 40-hour workweek). While the standard Monitoring Efforts workweek in Chinese provinces officially ranged The efforts of unscrupulous manufacturers in China from 40 to 44 hours, there were said to be numer- and other parts of the world to game the plant moni- ous instances where plant personnel worked 60 to toring system and use whatever deceptive practices 100 hours per week, sometimes with only one or two it took to successfully pass plant audits had four days off per month. Such long work hours meant chief elements: that the actual average manufacturing wage in China 1. Maintaining two sets of books-Factories gen- was likely well below $0.64 per hour in 2005-2006. erated a set of bogus payroll records and time According to estimates made by a veteran inspector sheets to show audit teams that their workers of Chinese factories, employees at garment, elec- were properly paid and received the appropri- tronics, and other plants making goods for export typically worked more than 80 hours per week and ate overtime pay; the genuine records were kept secret. For example, at an onsite audit of a earned an average of $0.42 per hour. Overtime pay rules in Chinese provinces of- Chinese maker of lamps for Home Depot, Sears, ficially called for time-and-a-half pay for all work and other retailers, plant managers provided inspectors with payroll records and time sheets over eight hours per day and between double and showing that employees worked a five-day triple pay for work on Saturdays, Sundays, and holi- week from 8 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. with a 30-minute days. However, it was commonplace for Chinese lunch break and no overtime hours; during inter- employers to disregard overtime pay rules, and views, managers at the plant said the records governmental enforcement of minimum wage and were accurate. But other records auditors found overtime requirements by both Beijing officials at the site, along with interviews with workers, and officials in local Chinese provinces was often indicated that employees worked an extra three minimal to nonexistent. At a Hong Kong garment to five hours daily with one or two days off per plant where 2,000 employees put in many overtime month during peak production periods; inspec- hours operating sewing and stitching machines, tors were unable to verify whether workers at worker pay averaged about $125 per month-an the plant received overtime pay. According amount that the owner acknowledged did not meet to a compliance manager at a major multina- Chinese overtime pay requirements. The owner said tional company who had overseen many factory that overtime rules were "a fantasy. Maybe in two audits, the percentage of Chinese employers or three decades we can meet them." Many young submitting false payroll records had risen from Chinese factory workers were tolerant of long 46 percent to 75 percent during the past four hours and less than full overtime pay because they years; the manager also estimated that onlyCase 29 Monitoring Foreign Suppliers: The Challenge of Detecting Unethical Practices C-413 20 percent of Chinese suppliers complied with local minimum-wage rules and that just 5 per- to be truthful and forthcoming about actual work- ing conditions and pay practices when top-level cent obeyed hour limitations." plant management could not trace the informa- Hiding the use of underage workers and unsafe tion given to inspectors back to them. work practices-In some instances, factories in China, parts of Africa, and select other coun- There was a growing awareness among compa- tries in Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle nies attempting to enforce supplier codes of conduct East employed underage workers. This was dis- that all factories across the world with substan- guised either by falsifying the personnel records dard working conditions and reasons to hide their of underage employees, by adeptly getting un- practices from outside view played cat-and-mouse derage employees off the premises when audit games with plant inspectors. In many less-developed teams arrived, or by putting underage employ- countries struggling to build a manufacturing base ces in back rooms concealed from auditors. A and provide jobs for their citizens, factory manag- memo distributed in one Chinese factory in- ers considered deceptive practices a necessary evil structed managers to "notify underage trainees, to survive, principally because improving wages underage full-time workers, and workers with- and working conditions to comply with labor codes out identification to leave the manufacturing and customers' codes of conduct for suppliers raised workshop through the back door. Order them costs and imperiled already thin profit margins. not to loiter near the dormitory area. Secondly, Violations were said to be most prevalent at factories immediately order the receptionist to gather all making apparel, but more violations were surfacing relevant documents and papers." At a toy plant in factories making furniture, appliances, toys, and in China, a compliance inspector, upon smell- electronics. ing strong fumes in a poorly ventilated building, However, large global corporations such as found young female employees on a production General Electric, Motorola, Dell, Nestle, and Toyota that owned and operated their own offshore line using spray guns to paint figurines; in a locked back room that a factory official initially manufacturing plants in China and other low-wage refused to open, an apparently underage worker countries had not been accused of mistreating their was found hiding behind co-workers, " employees or having poor working conditions. The offshore factories of well-known global and multina- 3. Meeting requirements by secretly shifting pro- tional companies were seldom subject to monitoring duction to subcontractors-On occasions, sup- by outsiders because the workplace environments in pliers met the standards set by customers by their foreign plants were relatively good in comparis secretly shifting some production to subcontract son to those of local manufacturing enterprises who tors who failed to observe pay standards, skirted made a business of supplying low-cost components worker safety procedures, or otherwise engaged and finished goods to companies and retailers in af- in abuses of various kinds. fluent, industrialized nations. 4. Coaching managers and employees on answer- ing questions posed by audit team members- Both managers and workers were tutored on what FOREIGN SUPPLIER to tell inspectors should they be interviewed. Scripting responses about wages and overtime COMPLIANCE PROGRAMS pay, hours worked, safety procedures, training. AT NIKE AND WAL-MART and other aspects related to working conditions was a common tactic for thwarting what in- Corporate sensitivity to charges of being socially ir- spectors could learn from interviews. However, responsible in their sourcing of goods from foreign in instances where plant inspectors were able manufacturers had prompted hundreds of companies to speak confidentially with employees away to establish supplier codes of conduct and to engage from the worksite, they often got information at in compliance monitoring efforts of one kind or an- variance with what they were told during onsite other manner. Most companies with global sourcing interviews-plant personnel were more inclined strategies and factory compliance programs workedC-414 Part 2 Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy proactively to improve working conditions globally, 16 for apparel and 18 for footwear; these age stan- preferring to help suppliers achieve the expected dards were more demanding than those set in 1991 standards rather than abruptly and permanently cut- and exceeded the International Labor Organization's ting off purchases. The most commonly observed age minimum of 15 years. problems worldwide related to benefits such as pen- sions and insurance (medical, accident, unemploy- Nike's System for Monitoring Contract Manu- ment) not being paid. Other frequent issues included facturers. During 2003-2006, Nike used three workers not being paid for all hours worked, the approaches to plant monitoring:3 use of false books, and incomplete or insufficient . Basic monitoring or SHAPE inspections: SHAPE documentation. inspections, used since 1997, sought to gauge a Nike and Wal-Mart were two companies with factory's overall compliance performance, include supplier codes of conduct and rather extensive pro- ing environment, safety, and health. They were grams to monitor whether suppliers in low-wage, low-cost manufacturing locations across the world typically performed by Nike's field-based pro- duction staff and could be completed in one day were complying with their codes of conduct. Both or less. Nike's stated goal was to conduct two companies initiated such efforts in the 1990s because SHAPE audits on each active factory each year, they came under fire from human rights activist but the actual number of such audits had fallen groups for allegedly sourcing goods from sweatshop short of that target. factories in China and elsewhere. In-depth M-Audits: The M-Audit was designed to provide a deeper measure of the working con- Nike's Supplier Code ditions within contract factories. As a general of Conduct and Compliance rule, Nike focused its plant inspection efforts on factories where noncompliance was most likely Monitoring Program to occur. Factories located in highly regulated Nike was the world's leading designer, distributor, countries where workers were more informed about their rights and workplace laws and regu- and marketer of athletic footwear, sports apparel, lations were enforced were deemed less likely to and sports equipment and accessories, but it did no be out of compliance. In 2003, Nike focused its manufacturing. All Nike products were sourced from M-audits on factories presumed to have the high- contract manufacturers. In April 2005, Nike reported est risk of noncompliance and the greatest size that there were over 730 factories actively engaged (as measured by worker population). In 2004 in manufacturing its products; of these, about 135 M-audits were focused on factories believed to were in China (including Hong Kong and Macau); 73 in Thailand, 39 in Indonesia, 35 in Korea, 34 in be of medium risk for noncompliance. Nike's stated goal was to conduct M-audits for approxi- Vietnam, 33 in Malaysia, 25 in Sri Lanka, and 18 in mately 25-33 percent of its active factory base India." Nike's contract factories employed roughly each year. The M-Audit included four major cat- 625,000 workers, the majority of whom were women egories of inquiry (hiring practices, worker treat- between the ages of 19 and 25 performing entry- ment, worker-management communications, and level, low-skill jobs. compensation) and covered more than 80 labor- Nike drafted a code of conduct for its contract management issues. factories in 1991, distributed the code to all of its In 2004 Nike had 46 employees who regularly contract factories in 1992, and directed them to conducted M-Audits. The typical M-Auditor was post the code in a visible place and in the appropri- under the age of 30, and 74 percent were women. ate local language. The code had been modified and Nike tried to hire auditors who were local na- updated over the years, and in 2007 also included a tionals and understood the local language and set of leadership standards that was adopted in 2002. culture. In 2003-2004, over 9.200 factory work- Nike's code of conduct is presented in Exhibit 2. In ers were individually interviewed as part of the 1998, in a move to strengthen its opposition to the M-Audit process. Each interview took approxi- use of child labor in factories, Nike directed its con- mately 30 minutes. The typical M-Audit took tract factories to set age standards for employment at an average of 48 hours to complete, includingExhibit 2 Nike's Code of Conduct for Its Suppliers and Contract Manufacturers, 2006 Nike, Inc. was founded on a handshake Implicit in that act was the determination that we would build our business with all of our partners based on trust, teamwork, honesty and mutual respect. We expect all of our business partners to operate on the same principles. At the core of the NIKE corporate ethic is the belief that we are a company comprised of many different kinds of people, appreciating individual diversity, and dedicated to equal opportunity for each individual. NIKE designs, manufactures, and markets products for sports and fitness consumers. At every stop in that process, we are driven to do not only what is required by law, but what is expected of a leader. We expect our business partners to do the same. NIKE partners with contractors who share our commitment to best practices and continuous improvement in: 1. Management practices that respect the rights of all employees, including the right to free association and collective bargaining 2. Minimizing our impact on the environment 3. Providing a safe and healthy workplace 4. Promoting the health and well-being of all employees Contractors must recognize the dignity of each employee, and the right to a workplace free of harassment, abuse or corporal punishment. Decisions on hiring, salary, benefits, advancement, termination or retirement must be based solely on the employee's ability to do the job. There shall be no discrimination based on race, creed, gender, marital or maternity status, religious or political beliefs, age or sexual orientation. Wherever NIKE operates around the globe we are guided by this Code of Conduct and we bind our contractors to these principles. Contractors must post this Code in all major workspaces, translated into the language of the employee, and must train employees on their rights and obligations as defined by this Code and applicable local laws, While these principles establish the spirit of our partnerships, we also bind our partners to specific standards of conduct. The core standards are set forth below. Forced Labor The contractor does not use forced labor in any form-prison, indentured, bonded or otherwise. Child Labor The contractor does not employ any person below the age of 18 to produce footwear, The contractor does not employ any person below the age of 16 to produce apparel, accessories or equipment. If at the time Nike production begins, the contractor employs people of the legal working age who are at least 15, that employment may continue, but the contractor will not hire any person going forward who is younger than the Nike or legal age limit, whichever is higher. To further ensure these age standards are complied with, the contractor does not use any form of homework for Nike production. Compensation The contractor provides each employee at least the minimum wage, or the prevailing industry wage, whichever is higher; provides each employee a clear, written accounting for every pay period; and does not deduct from employee pay for disciplinary infractions. Benefits The contractor provides each employee all legally mandated benefits. Hours of Work/Overtime The contractor complies with legally mandated work hours; uses overtime only when each employee is fully compensated according to local law; informs each employee at the time of hiring if mandatory overtime is a condition of employment; and on a regularly scheduled basis provides one day off in seven, and requires no more than 60 hours of work per week on a regularly scheduled basis, or complies with local limits if they are lower. Environment, Safety and Health (ES&H) The contractor has written environmental, safety and health policies and standards, and implements a system to minimize negative impacts on the environment, reduce work-related injury and illness, and promote the general health of employees. Documentation and Inspection The contractor maintains on file all documentation needed to demonstrate compliance with this Code of Conduct and required laws; agrees to make these documents available for Nike or its designated monitor; and agrees to submit to inspections with or without prior notice. Source: www.nike.com (accessed January 25, 2007).C-416 Part 2 Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy travel to and from the factory-travel hours ac- require in our evaluation of a factory is dependent counted for between 25 and 30 percent of total upon access to relevant records and individuals with- M-Audit time. in factory management." When a factory was found Independent external monitoring: Beginning in to be out of compliance with the code of conduct, 2003, Nike became a member of the Fair Labor Nike's compliance team worked with factory manage- Association, an organization that conducted inde- ment and the Nike business unit for which products pendent audits of factories that provided goods were being manufactured to develop a Master Action to members. The FLA applied a common set of Plan (MAP) that specified the factory's needed reme- compliance standards in all of its factory audits. diation efforts. The Nike production manager respon About 40 factories supplying goods to Nike sible for the business relationship with the contract were audited by the FLA in 2003. factory monitored MAP progress and exchanged In 2004, Nike's compliance team consisted of 90 information about progress or obstacles with Nike's people based in 24 offices in 21 countries. The typical country compliance team. The Nike general manager Nike compliance team in each country spent about for production monitored the progress of all factories one-third of their time on monitoring and auditing within his or her purview, and weighed in when fac- activities, about half their time assisting and tracking tory remediation progress was too slow. factory remediation activities, and the remainder of To further facilitate factory compliance with their time on troubleshooting and collaboration/out- Nike's Code of Conduct for suppliers, the company reach work." In its 2004 Corporate Responsibility conducted or sponsored training and education pro- Report, Nike said grams for factory personnel. In 2004, over 16,500 factory managers and workers attended programs re- With an average of one compliance staff for more lating to labor issues, worker health and safety, and than 10 factories-some of which are remote and environmental protection." some of which are large and complex businesses with 10,000 or more employees-tracking and assisting Nike's Compliance Rating System. Nike's fac- factory remediation is at times an overwhelming and tory ratings for SHAPE and M-Audits resulted incomplete body of work." in numeric scores ranging from 0 to 100 (a score of 100 indicated full compliance); these numeric Nike's factory audits were announced rather than scores were then converted to one of four overall unannounced because "much of the information we grades: 14 Grade Criteria No more than 5 minor violations on a factory's Master Action Plan for improving working conditions and achieving higher levels of compliance with Nike's Code of Conduct, and no more than 20 percent of MAP items past due. B No more than 5 minor violations, but no serious or critical issues outstanding on the MAP and no more than 30 percent of MAP items past due. C One or more C-level compliance issues outstanding on the MAP and no more than 30 percent of MAP items past due-examples of C-level issues included excessive work hours per week (more than 60 but less than 72), not providing 1 day off in 7, verbal or psychological harassment of workers, exceeding legal annual overtime work limit for 10% or more of workforce, conditions likely to lead to moderate injury or illness to workers, and conditions likely to lead to moderate harm to environment or community. D One or more D-level issues outstanding on the factory's MAP or past due correction of prior D-level issues; or more than 40 percent of open MAP items past due. Examples of D-level issues included unwillingness to comply with code standards, falsified records, coaching of workers to falsify information, use of underage workers or forced labor, paying below the legal wage, no verifiable timekeeping system, exceeding daily work hour limit or work in excess of more than 72 hours per week for more than 10% of workforce, not providing one day off in 14, and conditions that could lead to serious worker injury or harm to the environment.Case 29 Monitoring Foreign Suppliers: The Challenge of Detecting Unethical Practices C-417 Exhibit 3 Summary Results of Nike's Compliance Ratings for Contract Suppliers, Fiscal Years 2003-2004 Geographic Region Europe, Middle Northern Southern Worldwide Americas East, Africa Asia Asia Total Number of SHAPE 178 157 378 303 1,016 audits in 2004 Number of M-Audits 148 56 198 167 569 in 2003 and 2004 M-Audit Numeric Scores in 2003-2004 Lowest score 46 49 25 20 20 Average score 78 70 58 58 65 Highest score 94 96 95 95 99 Compliance Ratings for Contact Factories as of June 2004 Grade of A 32 15 34 25 106 (15%) Grade of B 64 40 147 76 327 (44%) Grade of C 18 7 33 65 123 (17%) Grade of D 5 35 14 8 62 (8%) Grade of E 18 22 70 117 (16%) Note: Worker population In M-Audited factories was 375,000 in fiscal year 2003 and 213,000 in fiscal year 2004. Source: Nike's 2004 Corporate Responsibility Report, pp. 20, 34, and 35. Exhibit 3 presents a summary of Nike's latest time. For example, a manufacturing group in South available factory ratings. Asia had performed poorly on a range of issues, Cutting Off Orders to Noncomplying or from overtime and worker-management communi- Nonperforming Suppliers. A factory was cut cation to the quality of product and shipping dates. from Nike's supplier base when, over a specified After a series of performance reviews, Nike manage- period, Nike management determined that factory ment informed the factory group that it would not management lacked the capacity or the will to cor- be placing orders for the next season. Nike did not rect serious issues of noncompliance. One supplier in report on factories dropped solely from noncompli- China, for example, was cited for repeated violations ance reasons related to its code of conduct because, of overtime standards and falsification of records. management said, "it is often difficult to isolate poor The compliance team established action plans, which performance on compliance as the sole reason for three different Nike business units worked with the terminating a business relationship."9 factory to implement. After six months of continu- To give its contract manufacturers greater in- ous efforts, and no improvement, the factory was centive to comply with Nike's workplace standards dropped. In November 2006, Nike severed its busi- and expectations, during crunch production periods ness relationship with a Pakistani supplier of soccer Nike management and plant auditors had given some balls that failed to correct serious code of conduct factories latitude to institute long workweeks (above violations. 72 hours) and not hold them to a strict standard of More typically, Nike's decisions to end a busi- I day off out of every 14 days if the employer gave ness relationship with problem suppliers was based workers more days off during slack production peri- on a balanced scorecard of factory performance that ods. Nike was also working to streamline its meth- took into account labor code compliance along with ods of designing shoes and placing orders with key such measures such as price, quality, and delivery suppliers and helping foreign factories develop moreC-418 Part 2 Cases in Crafting and Executing Strategy efficient production techniques, so as to help con- from offices in 23 countries, including China, tract factories eliminate the need to institute long Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, workweeks and excessive overtime. According to Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Mexico, Brazil, Nike's vice president for global footwear operations, and Turkey (countries where supplier compliance "If you improve efficiency and innovation, it changes the cost equation" for factories.20 presented big challenges). In 2005-2006, Wal-Mart purchased goods from about 7,200 factories in over 60 countries; about Wal-Mart's Supplier Code 2,000 of the 7,200 factories had recently come of Conduct and Compliance into Wal-Mart's compliance and factory audit sys- tem due to mergers, acquisitions, and new factory Monitoring Program construction. About 200 Wal-Mart personnel scat- In 1992, Wal-Mart established a set of standards tered across GPSG's offices in all 23 countries were for its suppliers and put in place an ethical stan- engaged in monitoring suppliers for compliance with Wal-Mart's standards for suppliers. Suppliers cov- dards program to monitor supplier compliance with ered by Wal-Mart's ethical standards program had to these standards." Since then, Wal-Mart's standards disclose the factory (or factories) used to fulfill each for suppliers had been periodically evaluated and order placed by Wal-Mart. modified based on experience and feedback from the ethical sourcing community. The company's stan- dards for suppliers covered compensation, working Wal-Mart's Supplier Auditing hours, forced labor, underage labor, discrimina- tion, compliance with applicable national laws and Program and Compliance regulation, health and safety practices, environmental Rating System abuse, freedom of association and collective bargain- During 2005, Wal-Mart audited more factories than ing, rights concerning foreign contract workers, and any other company in the world, performing 14,750 the right of audit by Wal-Mart. Prior to contracting with any supplier, Wal- initial and follow-up audits of 7,200 supplier fac- tories; in 2004, Wal-Mart conducted 12,561 fac- Mart required suppliers to review and sign a sup- tory audits. The company's audit methodology and plier agreement, which incorporated an expectation its factory rating system are described in Exhibit 4. that the supplier would comply with Wal-Mart's A summary of Wal-Mart's audit findings for 2004 standards for suppliers. In addition, it was manda- and 2005 is contained in Exhibit 5. Wal-Mart man- tory that all suppliers display Wal-Mart's "Standards agement said that the greater incidence of violations for Suppliers" poster in all of the suppliers' facto- in 2005 compared to 2004 was primarily due to a 100 ries. Factory management was required to sign that percent increase in unannounced audits, increased it had read and fully understood the "Standards rigor of supplier standards, a reclassification of vio- for Suppliers" poster, and a copy of the poster in lations to strengthen and reinforce their severity, the the relevant language had to be posted in a public implementation of team audits, and greater auditor place within the factory. Wal-Mart's "Standards for familiarity with the factories and their workers. Suppliers" poster was available in 25 languages. Rather than banning the placement of orders In February 2002, Wal-Mart created the Global at supplier factories receiving Yellow (medium-risk Procurement Services Group (GPSG), which was violations) and Orange (high-risk violations) rat- charged with identifying new suppliers, sourcing ings, Wal-Mart's policy was to work with supplier new products, building partnerships with existing factories to reduce violations and achieve steady suppliers, managing Wal-Mart's global supply chain improvement of workplace conditions, a position of direct imports, providing workplace standards widely endorsed by most human rights activists, training to suppliers, and enforcing compliance with concerned citizens groups, and nongovernmental Wal-Mart's supplier standards. All Wal-Mart per- agencies striving for better factory conditions for sonnel engaged in monitoring supplier compliance low-wage workers. To help promote higher levels became part of the GPSG organization. In 2007, of supplier compliance, Wal-Mart trained more than GPSG consisted of about 1,600 people working 8,000 supplier personnel in 2004 and another 1 1,000