Question: Please help! After reading Chapter 4, read Stowers v. Wolodzko, 386 Mich. 119, 191 N.W. 2d 355 (1971). In a two-page document address the following:

Please help!

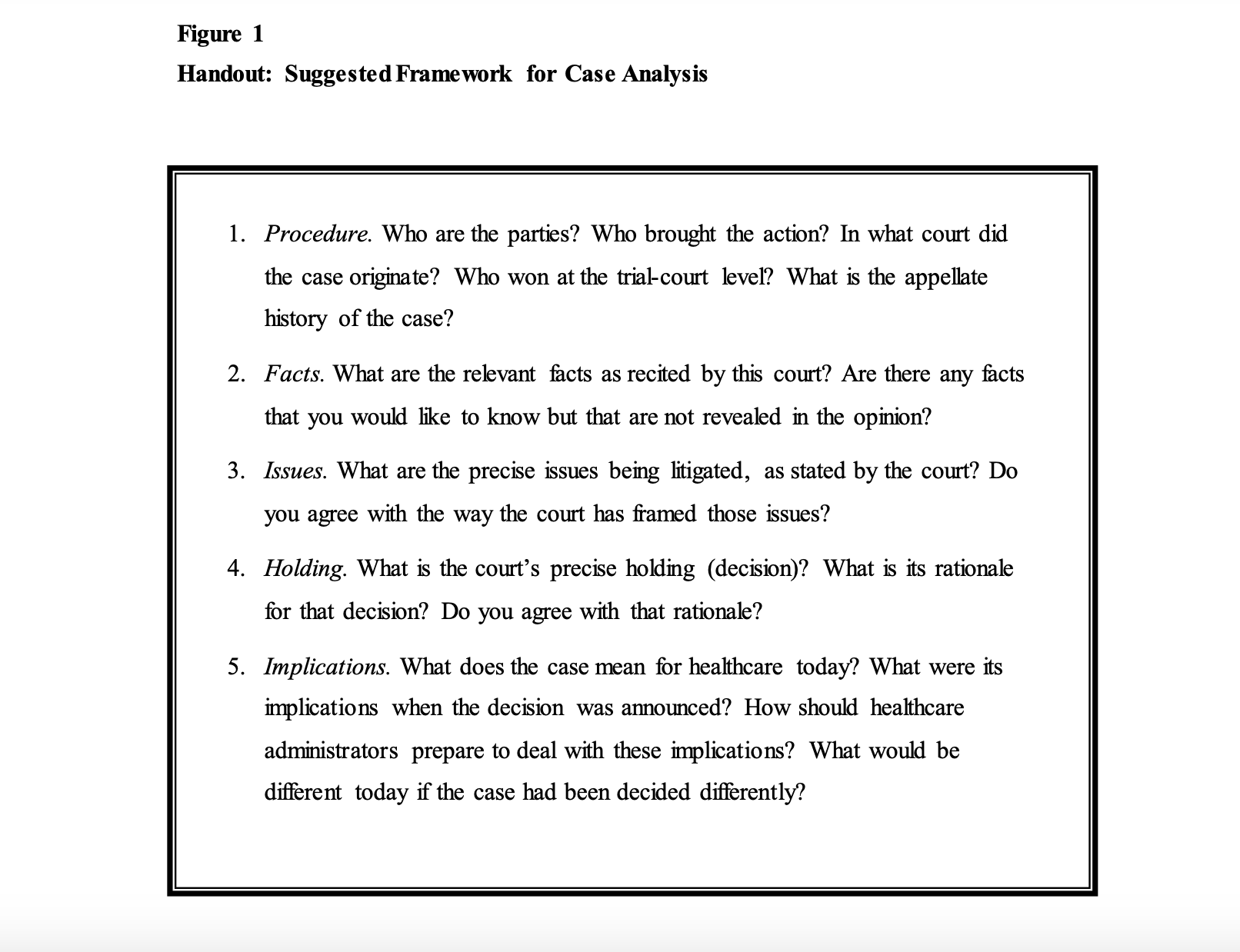

After reading Chapter 4, read Stowers v. Wolodzko, 386 Mich. 119, 191 N.W. 2d 355 (1971). In a two-page document address the following: Give a summary of the facts and issues in the case; Compare this case to current West Virginia Law regarding involuntary commitment and explain how you believe this case would be handled today - how would it be different from 1971? What additional information would be helpful in this case? Do you agree or disagree with the holding in this case? Why? (100 points) See Handout for suggested case analysis framework.

False Imprisonment False imprisonment arises from unlawful restriction of a person's freedom. Many false imprisonment cases involve patients who have been involuntarily committed to a mental hospital. In Stowers v. Wolodzko, a psychiatrist was held liable for his treatment of a patient who had been forcibly committed against her will.47 Although this type of commitment was allowed under state law, for many days the psychiatrist held the woman incommunicado and prevented her from calling an attorney or a relative. His actions amounted to false imprisonment because her freedom was unlawfully restrained. (The unusual facts of this case are laid out in The Court Decides at the end of this chapter.)

Stowers v. Wolodzko 386 Mich. 119, 191 N.W.2d 355 (1971) Swainson, J. [In court opinions, a jurist's position is often given by the addition of "J" or "CJ" behind the name. The initials stand for Judge or Justice, or Chief Judge or Chief Justice, depending on the title of the position in the particular jurisdiction. Members of the Michigan Supreme Court are known as justices, thus the Stowers decision was written by Justice Swainson.] This case presents complicated issues concerning the liability of a doctor for actions taken subsequent to a person's confinement in a private mental hospital pursuant to a valid court order. . . . Plaintiff, a housewife, resided in Livonia, Michigan, with her husband and children. She and her husband had been experiencing a great deal of marital difficulties and she testified that she had informed her husband . . . that she intended to file for a divorce. On December 6, 1963, defendant appeared at plaintiff's home and introduced himself as "Dr. Wolodzko." Dr. Wolodzko had never met either plaintiff or her husband before he came to the house. He stated that he had been called by the husband, who had asked him to examine plaintiff. Plaintiff testified that defendant told her that he was there to ask about her husband's back. She testified that she told him to ask her husband, and that she had no further conversation with him or her husband. She testified that he never told her that he was a psychiatrist. Dr. Wolodzko stated in his deposition . . . that he told plaintiff he was there to examine her. However, upon being questioned upon this point, he stated that he could "not specifically" recollect having told plaintiff that he was there to examine her. He stated in his deposition that he was sure that the fact he was a psychiatrist would have come out, but that he couldn't remember if he had told plaintiff that he was a psychiatrist. Plaintiff subsequently spoke to Dr. Wolodzko at the suggestion of a Livonia policewoman, following a domestic quarrel with her husband. He did inform her at that time that he was a psychiatrist. On December 30, 1963, defendant Wolodzko and Dr. Anthony Smyk, apparently at the request of plaintiff's husband and without the authorization, knowledge, or consent of plaintiff, signed a sworn statement certi- fying that they had examined plaintiff and found her to be mentally ill. Such certificate was filed with the Wayne County Probate Court on January 3, 1964, and on the same date an order was entered by the probate court for the temporary hospitalization of plaintiff until a sanity hearing could be held. The Judge ordered plaintiff committed to Ardmore Acres, a privately operated institution, pursuant to the provisions of [Michigan law]. Plaintiff was transported to Ardmore Acres on January 4, 1964. . . . The parties are in substantial agree ment as to what occurred at Ardmore Acres. Defendant requested permission to treat the plaintiff on several different occasions, and she refused. For six days, she was placed in the "security room," which was a bare room except for the bed. The windows of the room were covered with wire mesh. During five of the six days, plaintiff refused to eat, and at all times refused medication. Defendant telephoned orders to the hospital and prescribed certain medication. He visited her often during her stay. When plaintiff arrived at the hospital she was refused permission to receive or place telephone calls, or to receive or write letters. Dr. Wolodzko conceded at the trial that plaintiff wished to contact her brother in Texas by telephone and that he forbade her to do so. After nine days, she was allowed to call her family, but no one else. Plaintiff testified on direct examination that once during her hospitalization she asked one of her children to call her relatives in Texas and that defendant took her to her room and told her, "Mrs. Stowers, don't try that again. If you do, you will never see your children again." It is undisputed that plaintiff repeatedly requested permission to call an attorney and that Dr. Wolodzko refused such permission. At one point when plaintiff refused medication, on the written orders of defendant, she was held by three nurses and an attendant and was forcibly injected with the medication. Hospital personnel testified at the trial that the orders concerning medication and deprivation of communication were pursuant to defendant's instructions. Plaintiff, by chance, found an unlocked telephone near the end of her hospitalization and made a call to her relatives in Texas. She was released by court order on January 27, 1964. Plaintiff filed suit alleging false imprisonment, assault and battery, and malpractice, against defendant Wolodzko, Anthony Smyk and Ardmore Acres. Defendants Ardmore Acres and Smyk were dismissed prior to trial. At the close of plaintiff's proofs, defendant moved for a directed verdict. The court granted the motion as to the count of malpractice only, but allowed the counts of assault and battery and false imprisonment to go to the jury. At the Conclusion of the trial, the jury returned a verdict for plaintiff in the sum of $40,000. . . . Defendant has raised five issues on appeal. . . .

. . . The second issue involves whether or not there was evidence from which a jury could find false imprisonment. "False imprisonment is the unlawful restraint of an individual's personal liberty or freedom of locomotion." [Citation omitted.] It is clear that plaintiff was restrained against her will. Defendant, however, contends that because the detention was pursuant to court order (and hence not unlawful), there can be no liability for false imprisonment. However, defendant was not found liable for admitting or keeping plaintiff in Ardmore Acres. His liability stems from the fact that after plaintiff was taken to Ardmore Acres, defendant held her incommunicado and prevented her from attempting to obtain her release, pursuant to law. Holding a person incommunicado is clearly a restraint of one's freedom, sufficient to allow a jury to find false imprisonment. Defendant contends that it was proper for him to restrict plaintiff's communication with the outside world. Defendant's witness, Dr. Sidney Bolter, testified that orders restricting communications and visitors are customary in cases of this type. Hence, defendant contends these orders were lawful and could not constitute the basis for an action of false imprisonment. However, the testimony of Dr. Bolter is not conclusive on this point. . . . Psychiatrists have a great deal of power over their patients. In the case of a person confined to an institution, this power is virtually unlimited. All professions (including the legal profession) contain unscrupulous individuals who use their position to injure others. The law must provide protection against the torts committed by these individuals. In the case of mental patients, in order to have this protection, they must be able to communicate with the outside world.

In our country, even a person who has committed the most abominable crime has the right to consult with an attorney. Our Court and the courts of our sister States have recognized that interference with attempts of persons incarcerated to obtain their freedom may constitute false imprisonment. Further, we have jealously protected the individual's rights by providing that a circuit Judge "who willfully or corruptly refuses or neglects to consider an application, action, or motion for, habeas corpus is guilty of mal-feasance in office." [Citation omitted.]. . . [P]laintiff was . . . attempting to communicate with a lawyer or relative in order to obtain her release. Defendant prevented her from doing so. We . . . hold that the actions on the part of defendant constitute false imprisonment. . . .A person temporarily committed to an institution pursuant to statute certainly must have the right to make telephone calls to an attorney or relatives. We realize that it may be necessary to restrict visits to a patient confined to a mental institution. However, the same does not apply to the right of a patient to call an attorney or relative for aid in obtaining his release. This does not mean that an individual has an unlimited right to make numerous telephone calls, once he is confined pursuant to statute. Rather, it does mean that such an individual does have a right to communicate with an attorney and/or a relative in attempt to obtain his release. Dr. Bolter was unable to give any valid reason why a person should not be allowed to consult with an attorney. We do not believe there is such a reason. While problems may be caused in a few cases because of this requirement, the facts in the instant case provide cogent reasons as to why such a rule is necessary. Mrs. Stowers was able to obtain her release after she made the telephone call to her relatives and they, in turn, obtained an attorney for her. Prior to this, because of the order of no communications, she was virtually held a prisoner with no chance of redress. We, therefore, agree with the Court of Appeals that there was sufficient evidence from which a jury could find that Dr. Wolodzko had committed false imprisonment. The Court of Appeals is affirmed.

Figure 1 Handout: Suggested Framework for Case Analysis 1. Procedure. Who are the parties? Who brought the action? In what court did the case originate? Who won at the trial-court level? What is the appellate history of the case? 2. Facts. What are the relevant facts as recited by this court? Are there any facts that you would like to know but that are not revealed in the opinion? 3. Issues. What are the precise issues being litigated, as stated by the court? Do you agree with the way the court has framed those issues? 4. Holding. What is the court's precise holding (decision)? What is its rationale for that decision? Do you agree with that rationale? 5. Implications. What does the case mean for healthcare today? What were its implications when the decision was announced? How should healthcare administrators prepare to deal with these implications? What would be different today if the case had been decided differently

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts