Question: *Please read first before answering the 3 Case questions.* *Explain your answers in full details and include a reference! (minimum of 3 sentences per question.)*

*Please read first before answering the 3 Case questions.*

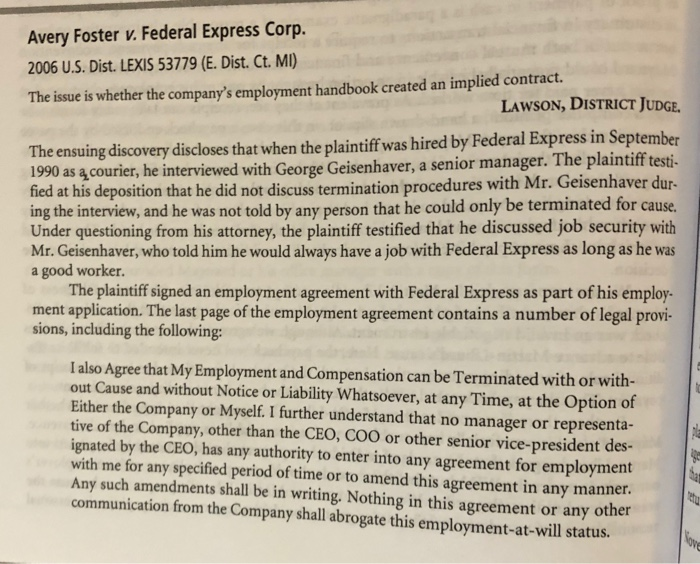

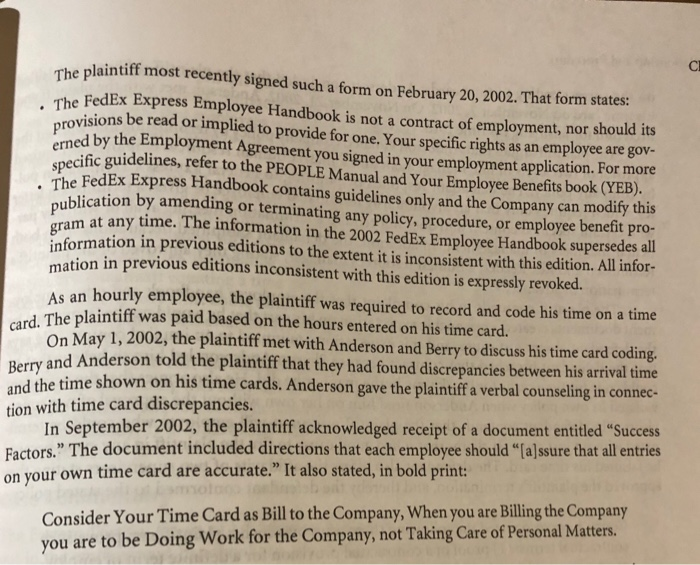

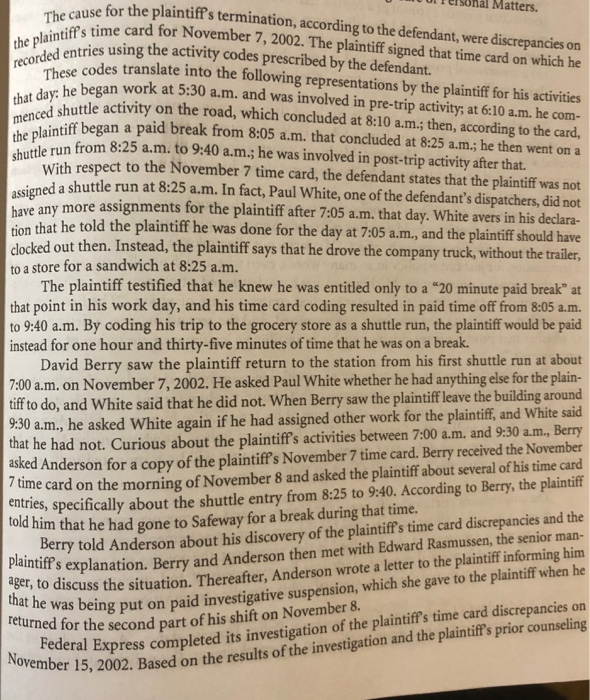

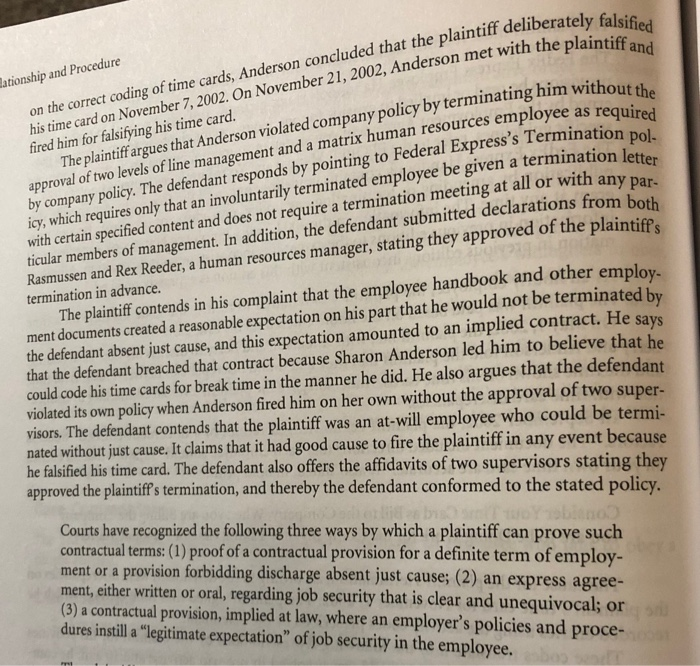

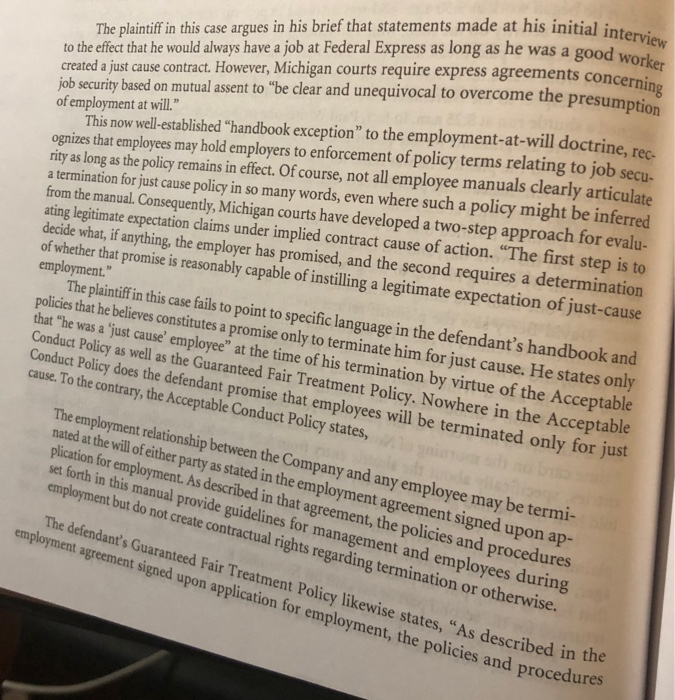

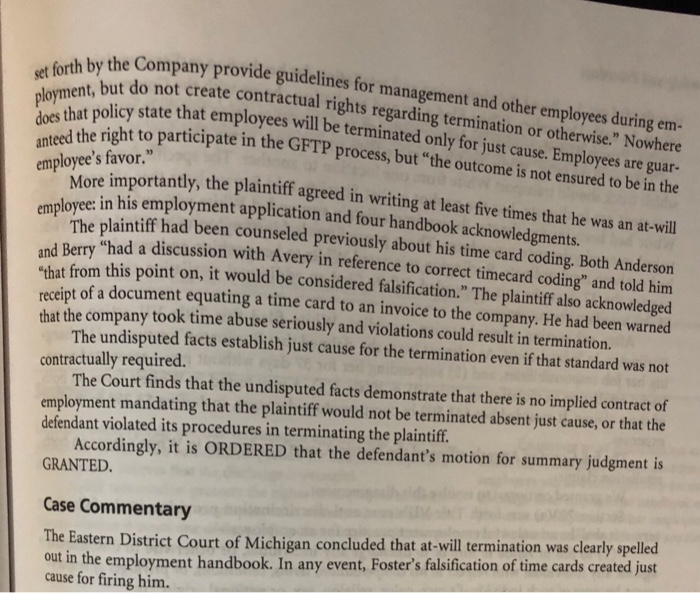

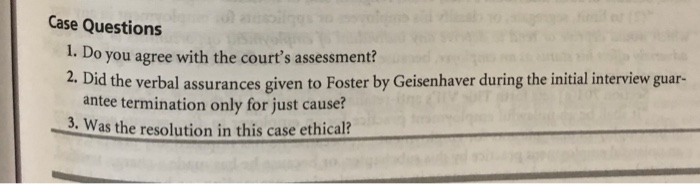

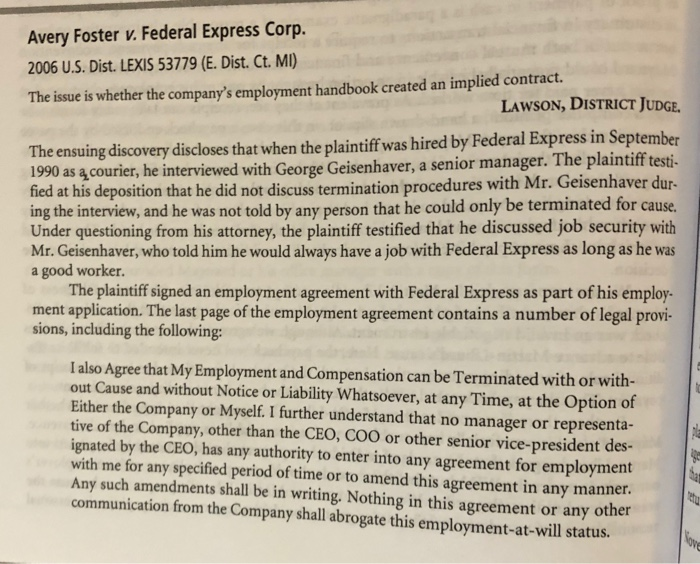

Avery Foster v. Federal Express Corp. 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 53779 (E. Dist. Ct. MI) The issue is whether the company's employment handbook created an implied contract. LAWSON, DISTRICT JUDGE. The ensuing discovery discloses that when the plaintiff was hired by Federal Express in September 1990 as 4 courier, he interviewed with George Geisenhaver, a senior manager. The plaintiff testi- fied at his deposition that he did not discuss termination procedures with Mr. Geisenhaver dur- ing the interview, and he was not told by any person that he could only be terminated for cause. Under questioning from his attorney, the plaintiff testified that he discussed job security with Mr. Geisenhaver, who told him he would always have a job with Federal Express as long as he was a good worker The plaintiff signed an employment agreement with Federal Express as part of his employ- ment application. The last page of the employment agreement contains a number of legal provi- sions, including the following: I also Agree that My Employment and Compensation can be Terminated with or with- out Cause and without Notice or Liability whatsoever, at any time, at the Option of Either the Company or Myself. I further understand that no manager or representa- tive of the Company, other than the CEO, COO or other senior vice-president des- ignated by the CEO, has any authority to enter into any agreement for employment with me for any specified period of time or to amend this agreement in any manner. Any such amendments shall be in writing. Nothing in this agreement or any other communication from the Company shall abrogate this employment-at-will status. publication by amending or terminating any policy, procedure, or employee benefit pro- The plaintiff most recently signed such a form on February 20, 2002. That form states: . The FedEx Express Employee Handbook is not a contract of employment, nor should its provisions be read or implied to provide for one. Your specific rights as an employee are gov- erned by the Employment Agreement you signed in your employment application. For more specific guidelines, refer to the PEOPLE Manual and Your Employee Benefits book (Y.EB), The FedEx Express Handbook contains guidelines only and the Company can modify this gram at any time. The information in the 2002 FedEx Employee Handbook supersedef all information in previous editions to the extent it is inconsistent with this edition. All infor- mation in previous editions inconsistent with this edition is expressly revoked. As an hourly employee, the plaintiff was required to record and code his time on a time card. The plaintiff was paid based on the hours entered on his time card. On May 1, 2002, the plaintiff met with Anderson and Berry to discuss his time card coding. Berry and Anderson told the plaintiff that they had found discrepancies between his arrival time and the time shown on his time cards. Anderson gave the plaintiff a verbal counseling in connec- tion with time card discrepancies. In September 2002, the plaintiff acknowledged receipt of a document entitled Success Factors. The document included directions that each employee should [a]ssure that all entries on your own time card are accurate. It also stated, in bold print: Consider Your Time Card as Bill to the Company, When you are Billing the Company you are to be Doing Work for the Company, not Taking Care of Personal Matters. November 15, 2002. Based on the results of the investigation and the plaintiff's prior counseling Matters. at The cause for the plaintiff's termination, according to the defendant, were discrepancies on the plaintiff's time card for November 7, 2002. The plaintiff signed that time card on which he recorded entries using the activity codes prescribed by the defendant. These codes translate into the following representations by the plaintiff for his activities menced shuttle activity on the road, which concluded at 8:10 a.m.; then, according to the card, shuttle run from 8:25 a.m. to 9:40 a.m.; he was involved in post-trip activity after that. that he was being put on paid investigative suspension, which she gave to the plaintiff when he returned for the second part of his shift on November 8. With respect to the November 7 time card, the defendant states that the plaintiff was not assigned a shuttle run at 8:25 a.m. In fact, Paul White, one of the defendant's dispatchers , did not have any more assignments for the plaintiff after 7:05 a.m. that day. White avers in his declara- tion that he told the plaintiff he was done for the day at 7:05 a.m., and the plaintiff should have clocked out then. Instead, the plaintiff says that he drove the company truck, without the trailer, to a store for a sandwich at 8:25 a.m. The plaintiff testified that he knew he was entitled only to a 20 minute paid break" at that point in his work day, and his time card coding resulted in paid time off from 8:05 a.m. to 9:40 a.m. By coding his trip to the grocery store as a shuttle run, the plaintiff would be paid instead for one hour and thirty-five minutes of time that he was on a break. David Berry saw the plaintiff return to the station from his first shuttle run at about 7:00 a.m. on November 7, 2002. He asked Paul White whether he had anything else for the plain- tiff to do, and White said that he did not. When Berry saw the plaintiff leave the building around 9:30 a.m., he asked White again if he had assigned other work for the plaintiff, and White said that he had not. Curious about the plaintiff's activities between 7:00 a.m. and 9:30 a.m., Berry asked Anderson for a copy of the plaintiff's November 7 time card. Berry received the November | 7 time card on the morning of November 8 and asked the plaintiff about several of his time card entries, specifically about the shuttle entry from 8:25 to 9:40. According to Berry, the plaintiff told him that he had gone to Safeway for a break during that time. Berry told Anderson about his discovery of the plaintiff's time card discrepancies and the plaintiff's explanation. Berry and Anderson then met with Edward Rasmussen, the senior man eger, to discuss the situation. Thereafter, Anderson wrote a letter to the plaintiff informing him Federal Express completed its investigation of the plaintiff's time card discrepancies on on the correct coding of time cards, Anderson concluded that the plaintiff deliberately falsified his time card on November 7, 2002. On November 21, 2002, Anderson met with the plaintiff and The plaintiff argues that Anderson violated company policy by terminating him without the approval of two levels of line management and a matrix human resources employee as required by company policy. The defendant responds by pointing to Federal Express's Termination pol- with certain specified content and does not require a termination meeting at all or with any par- icy, which requires only that an involuntarily terminated employee be given a termination letter lationship and Procedure fired falsifying his time ticular members of management. In addition, the defendant submitted declarations from both Rasmussen and Rex Reeder, a human resources manager, stating they approved of the plaintiffs termination in advance. The plaintiff contends in his complaint that the employee handbook and other employ- ment documents created a reasonable expectation on his part that he would not be terminated by the defendant absent just cause, and this expectation amounted to an implied contract. He says that the defendant breached that contract because Sharon Anderson led him to believe that he could code his time cards for break time in the manner he did. He also argues that the defendant violated its own policy when Anderson fired him on her own without the approval of two super- visors. The defendant contends that the plaintiff was an at-will employee who could be termi- nated without just cause. It claims that it had good cause to fire the plaintiff in any event because he falsified his time card. The defendant also offers the affidavits of two supervisors stating they approved the plaintiffs termination, and thereby the defendant conformed to the stated policy. obno Courts have recognized the following three ways by which a plaintiff can prove such contractual terms: (1) proof of a contractual provision for a definite term of employ- ment or a provision forbidding discharge absent just cause; (2) an express agree- ment, either written or oral, regarding job security that is clear and unequivocal; or (3) a contractual provision, implied at law, where an employer's policies and proce- dures instill a legitimate expectation" of job security in the employee. to the effect that he would always have a job at Federal Express as long as he was a good worker The plaintiff in this case argues in his brief that statements made at his initial interview created a just cause contract. However, Michigan courts require express agreements concerning of employment at will." job security based on mutual assent to be clear and unequivocal to overcome the presumption This now well-established handbook exception to the employment-at-will doctrine, rec- ognizes that employees may hold employers to enforcement of policy terms relating to job secu- rity as long as the policy remains in effect. Of course, not all employee manuals clearly articulate a termination for just cause policy in so many words, even where such a policy might be inferred from the manual. Consequently, Michigan courts have developed a two-step approach for evalu- ating legitimate expectation claims under implied contract cause of action. "The first step is to decide what, if anything, the employer has promised, and the second requires a determination of whether that promise is reasonably capable of instilling a legitimate expectation of just-cause employment." The plaintiff in this case fails to point to specific language in the defendant's handbook and policies that he believes constitutes a promise only to terminate him for just cause. He states only that "he was a "just cause' employee" at the time of his termination by virtue of the Acceptable Conduct Policy as well as the Guaranteed Fair Treatment Policy. Nowhere in the Acceptable Conduct Policy does the defendant promise that employees will be terminated only for just cause. To the contrary, the Acceptable Conduct Policy states, The employment relationship between the Company and any employee may be termi- nated at the will of either party as stated in the employment agreement signed upon ap- plication for employment. As described in that agreement, the policies and procedures set forth in this manual provide guidelines for management and employees during employment but do not create contractual rights regarding termination or otherwise. The defendant's Guaranteed Fair Treatment Policy likewise states, As described in the employment agreement signed upon application for employment, the policies and procedures employee's favor. set forth by the Company provide guidelines for management and other employees during em- does that policy state that employees will be terminated only for just cause. Employees are guar- ployment, but do not create contractual rights regarding termination or otherwise." Nowhere anteed the right to participate in the GFTP process, but the outcome is not ensured to be in the employee: in his employment application and four handbook acknowledgments. More importantly, the plaintiff agreed in writing at least five times that he was an at-will The plaintiff had been counseled previously about his time card coding. Both Anderson and Berryhad a discussion with Avery in reference to correct timecard coding and told him "that from this point on, it would be considered falsification. The plaintiff also acknowledged receipt of a document equating a time card to an invoice to the company. He had been warned that the company took time abuse seriously and violations could result in termination. The undisputed facts establish just cause for the termination even if that standard was not contractually required. The Court finds that the undisputed facts demonstrate that there is no implied contract of employment mandating that the plaintiff would not be terminated absent just cause, or that the defendant violated its procedures in terminating the plaintiff. Accordingly, it is ORDERED that the defendant's motion for summary judgment is GRANTED. Case Commentary The Eastern District Court of Michigan concluded that at-will termination was clearly spelled out in the employment handbook. In any event, Foster's falsification of time cards created just cause for firing him. Case Questions 1. Do you agree with the court's assessment? 2. Did the verbal assurances given to Foster by Geisenhaver during the initial interview guar- antee termination only for just cause? 3. Was the resolution in this case ethical *Explain your answers in full details and include a reference! (minimum of 3 sentences per question.)*

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock