Question: Please read the article about strategy and performance and provide a detailed summary of the main argument and learning points. Feel free to include your

Please read the article about strategy and performance and provide a detailed summary of the main argument and learning points. Feel free to include your thoughts and tie it back to any related materials. What did you find most interesting? Did you disagree with anything? Preferably a couple of pages long.

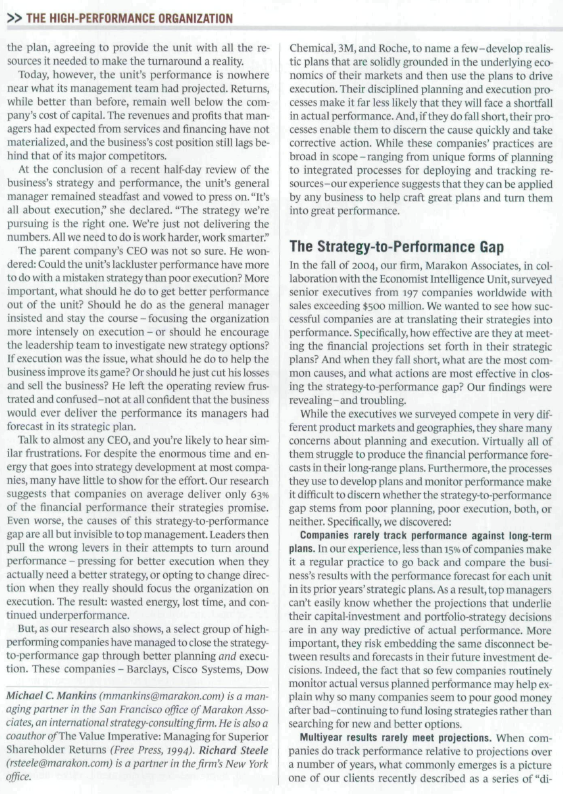

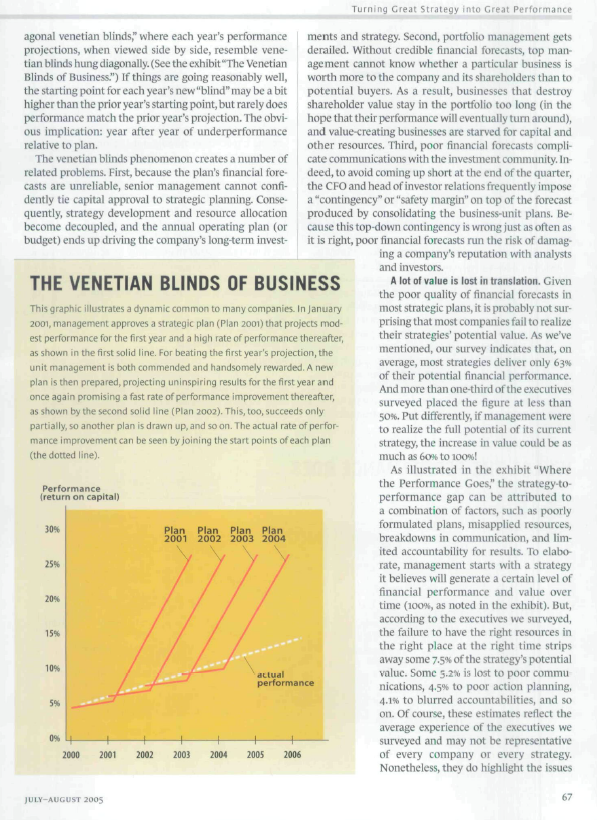

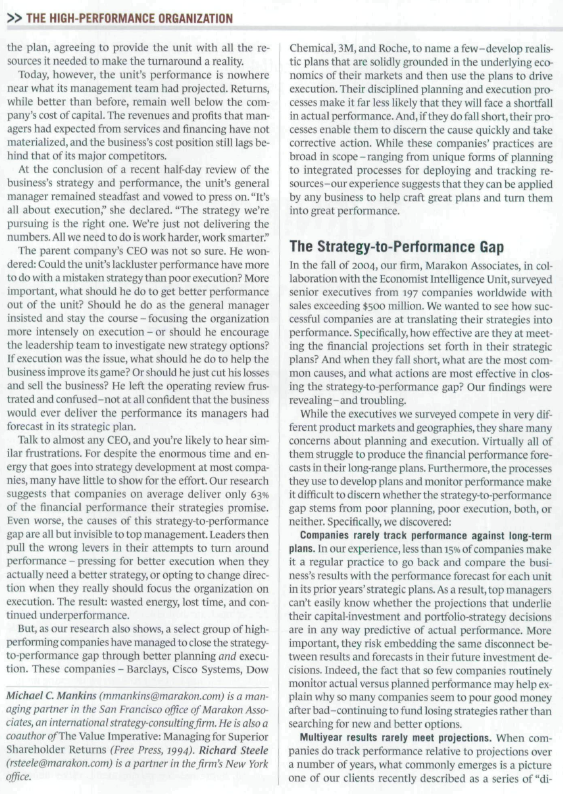

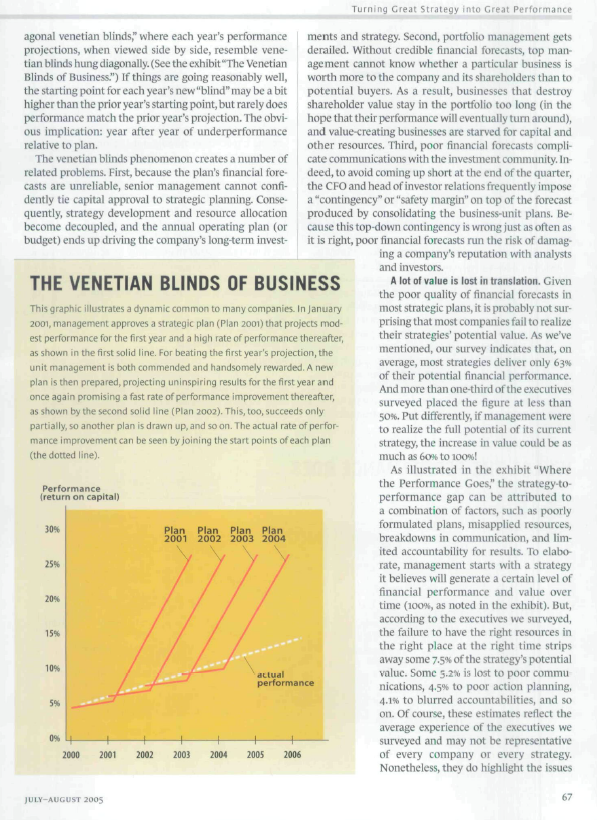

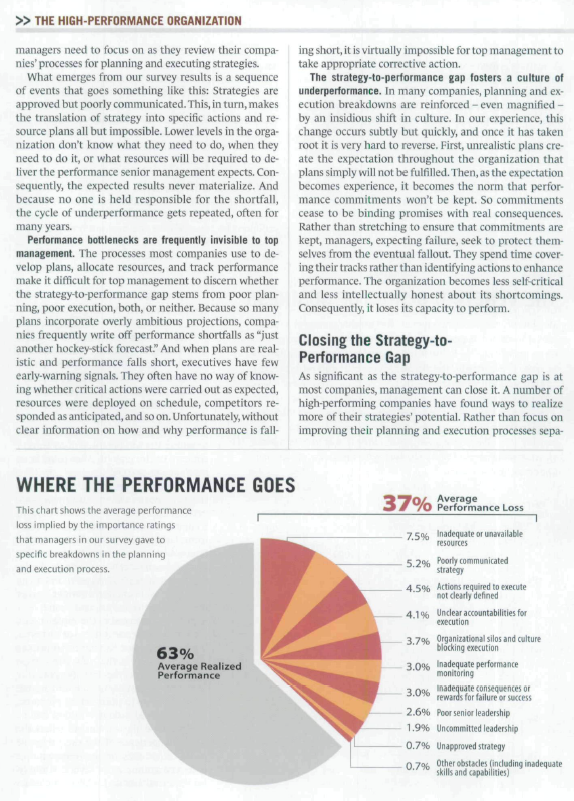

hree years ago, the leadership team at a major man- ufacturer spent months developing a new strategy for its European business. Over the prior half-decade, six new competitors had entered the market, each deploy- ing the latest in low-cost manufacturing technology and slashing prices to gain market share. The performance of the European unit - once the crown jewel of the com- pany's portfolio - had deteriorated to the point that top management was scriously considering divesting it. To turn around the operation, the unit's leadership team had recommended a bold new "solutions strategy"-one that would leverage the business's installed base to fuel growth in after-market services and equipment financing The financial forecasts were exciting-the strategy prom- ised to restore the business's industry-leading returns and growth. Impressed, top management quickly approved >> THE HIGH-PERFORMANCE ORGANIZATION the plan, agreeing to provide the unit with all the re- Chemical, 3M, and Roche, to name a few-develop realis- sources it needed to make the turnaround a reality. tic plans that are solidly grounded in the underlying eco- Today, however, the unit's performance is nowhere nomics of their markets and then use the plans to drive near what its management team had projected. Returns, execution. Their disciplined planning and execution pro- while better than before, remain well below the com- cesses make it far less likely that they will face a shortfall pany's cost of capital. The revenues and profits that man- in actual performance. And, if they do fall short, their pro- agers had expected from services and financing have not cesses enable them to discern the cause quickly and take materialized, and the business's cost position still lags be corrective action. While these companies' practices are hind that of its major competitors. broad in scope-ranging from unique forms of planning At the conclusion of a recent half-day review of the to integrated processes for deploying and tracking re- business's strategy and performance, the unit's general sources - our experience suggests that they can be applied manager remained steadfast and vowed to press on. "It's by any business to help craft great plans and turn them all about execution," she declared. "The strategy we're into great performance. pursuing is the right one. We're just not delivering the numbers. All we need to do is work harder, work smarter." The parent company's CEO was not so sure. He won The Strategy-to-Performance Gap dered: Could the unit's lackluster performance have more In the fall of 2004, our firm, Marakon Associates, in col- to do with a mistaken strategy than poor execution? More laboration with the Economist Intelligence Unit, surveyed important, what should he do to get better performance senior executives from 197 companies worldwide with out of the unit? Should he do as the general manager sales exceeding $500 million. We wanted to see how suc- insisted and stay the course - focusing the organization cessful companies are at translating their strategies into more intensely on execution - or should he encourage performance. Specifically, how effective are they at meet the leadership team to investigate new strategy options? ing the financial projections set forth in their strategic If execution was the issue, what should he do to help the plans? And when they fall short, what are the most com- business improve its game? Or should he just cut his losses mon causes, and what actions are most effective in clos- and sell the business? He left the operating review frusing the strategy to performance gap? Our findings were trated and confused-not at all confident that the business revealing and troubling. would ever deliver the performance its managers had While the executives we surveyed compete in very dif- forecast in its strategic plan. ferent product markets and geographies, they share many Talk to almost any CEO, and you're likely to hear sim- concerns about planning and execution. Virtually all of ilar frustrations. For despite the enormous time and en- them struggle to produce the financial performance fore- ergy that goes into strategy development at most compa casts in their long-range plans. Furthermore, the processes nies, many have little to show for the effort. Our research they use to develop plans and monitor performance make suggests that companies on average deliver only 63% it difficult to discern whether the strategy-to-performance of the financial performance their strategies promise. gap stems from poor planning, poor execution, both, or Even worse, the causes of this strategy to performance neither. Specifically, we discovered: gap are all but invisible to top management Leaders then Companies rarely track performance against long-term pull the wrong levers in their attempts to turn around plans. In our experience, less than 15% of companies make performance - pressing for better execution when they it a regular practice to go back and compare the busi- actually need a better strategy, or opting to change direc ness's results with the performance forecast for each unit tion when they really should focus the organization on in its prior years' strategic plans. As a result, top managers execution. The result: wasted energy, lost time, and con- can't easily know whether the projections that underlie tinued underperformance. their capital-investment and portfolio-strategy decisions But, as our research also shows, a select group of high- are in any way predictive of actual performance. More performing companies have managed to close the strategy important, they risk embedding the same disconnect be- to-performance gap through better planning and execu- tween results and forecasts in their future investment de- tion. These companies - Barclays, Cisco Systems, Dow cisions. Indeed, the fact that so few companies routinely monitor actual versus planned performance may help ex Michael C. Mankins (mmankins@marakon.com) is a man- plain why so many companies seem to pour good money aging partner in the San Francisco office of Marakon Asso- after bad-continuing to fund losing strategies rather than ciates, an international strategy-consulting firm. He is also a searching for new and better options. coauthor of The Value Imperative: Managing for Superior Multiyear results rarely meet projections. When com- Shareholder Returns (Free Press, 1994). Richard Steele panies do track performance relative to projections over (rsteele@marakon.com) is a partner in the firm's New York a number of years, what commonly emerges is a picture office. one of our clients recently described as a series of "di- Turning Great Strategy into Great Performance agonal venetian blinds," where each year's performance ments and strategy. Second, portfolio management gets projections, when viewed side by side, resemble vene- derailed. Without credible financial forecasts, top man tian blinds hung diagonally. (See the exhibit "The Venetian agement cannot know whether a particular business is Blinds of Business.") If things are going reasonably well worth more to the company and its shareholders than to the starting point for each year's new "blind"may be a bit potential buyers. As a result, businesses that destroy higher than the prior year's starting point, but rarely does shareholder value stay in the portfolio too long in the performance match the prior year's projection. The obvi- hope that their performance will eventually tum around), ous implication: year after year of underperformance and value-creating businesses are starved for capital and relative to plan. other resources. Third, poor financial forecasts compli- The venetian blinds phenomenon creates a number of cate communications with the investment community. In- related problems. First, because the plan's financial fore deed, to avoid coming up short at the end of the quarter, casts are unreliable, senior management cannot confi- the CFO and head of investor relations frequently impose dently tie capital approval to strategic planning, Conse a "contingency" or "safety margin" on top of the forecast quently, strategy development and resource allocation produced by consolidating the business-unit plans. Be become decoupled, and the annual operating plan (or cause this top-down contingency is wrong just as often as budget) ends up driving the company's long-term invest- it is right, poor financial forecasts run the risk of damag- ing a company's reputation with analysts and investors. THE VENETIAN BLINDS OF BUSINESS A lot of value is lost in translation. Given the poor quality of financial forecasts in This graphic illustrates a dynamic common to many companies. In January most strategic plans, it is probably not sur- 2001, management approves a strategic plan (Plan 2001) that projects mod- prising that most companies fail to realize est performance for the first year and a high rate of performance thereafter, their strategies' potential value. As we've as shown in the first solid line. For beating the first year's projection, the mentioned, our survey indicates that, on unit management is both commended and handsomely rewarded. A new average, most strategies deliver only 63% plan is then prepared, projecting uninspiring results for the first year and of their potential financial performance. And more than one-third of the executives once again promising a fast rate of performance improvement thereafter, surveyed placed the figure at less than as shown by the second solid line (Plan 2002). This, too, succeeds only 50%. Put differently, if management were partially, so another plan is drawn up, and so on. The actual rate of perfor to realize the full potential of its current mance improvement can be seen by joining the start points of each plan strategy, the increase in value could be as (the dotted line) much as 60% to 100%! As illustrated in the exhibit "Where Performance the Performance Goes," the strategy-to- return on capital) performance gap can be attributed to a combination of factors, such as poorly formulated plans, misapplied resources, breakdowns in communication, and lim- ited accountability for results. To elabo- 25% rate, management starts with a strategy it believes will generate a certain level of financial performance and value over time (100%, as noted in the exhibit). But, according to the executives we surveyed, the failure to have the right resources in the right place at the right time strips away some 7.5% of the strategy's potential value. Some 5.2% is lost to poor commu nications, 4.5% to poor action planning, 4.1% to blurred accountabilities, and so on. Of course, these estimates reflect the average experience of the executives we surveyed and may not be representative 2001 2002 of every company or every strategy. Nonetheless, they do highlight the issues 30% Plan Plan Plan Plan 2001 2002 2003 2004 20% 15% 10% actual performance 5% 0% 2000 2003 2004 2005 2006 JULY-AUGUST 2005 67 >> THE HIGH-PERFORMANCE ORGANIZATION managers need to focus on as they review their compa- ing short, it is virtually impossible for top management to nies' processes for planning and executing strategies. take appropriate corrective action. What emerges from our survey results is a sequence The strategy-to-performance gap fosters a culture of of events that goes something like this: Strategies are underperformance. In many companies, planning and ex approved but poorly communicated. This, in turn, makes ecution breakdowns are reinforced - even magnified- the translation of strategy into specific actions and re- by an insidious shift in culture. In our experience, this source plans all but impossible. Lower levels in the orga- change occurs subtly but quickly, and once it has taken nization don't know what they need to do, when they root it is very hard to reverse. First, unrealistic plans cre- need to do it, or what resources will be required to deate the expectation throughout the organization that liver the performance senior management expects. Con plans simply will not be fulfilled. Then, as the expectation sequently, the expected results never materialize. And becomes experience, it becomes the norm that perfor- because no one is held responsible for the shortfall , mance commitments won't be kept. So commitments the cycle of underperformance gets repeated, often for cease to be binding promises with real consequences. many years. Rather than stretching to ensure that commitments are Performance bottlenecks are frequently invisible to top kept, managers, expecting failure, seek to protect them- management. The processes most companies use to de selves from the eventual fallout. They spend time cover- velop plans, allocate resources, and track performance ing their tracks rather than identifying actions to enhance make it difficult for top management to discem whether performance. The organization becomes less self-critical the strategy-to-performance gap stems from poor plan and less intellectually honest about its shortcomings. ning, poor execution, both, or neither. Because so many Consequently, it loses its capacity to perform. plans incorporate overly ambitious projections, compa- nies frequently write off performance shortfalls as "just closing the Strategy-to- another hockey-stick forecast." And when plans are real- istic and performance falls short, executives have few Performance Gap early-warning signals. They often have no way of know- As significant as the strategy-to-performance gap is at ing whether critical actions were carried out as expected, most companies, management can close it. A number of resources were deployed on schedule, competitors re- high-performing companies have found ways to realize sponded as anticipated, and so on. Unfortunately, without more of their strategies' potential. Rather than focus on clear information on how and why performance is fall- improving their planning and execution processes sepa- Average 37% Performance Loss WHERE THE PERFORMANCE GOES This chart shows the average performance loss implied by the importance ratings that managers in our survey gave to specific breakdowns in the planning and execution process. 63% Average Realized Performance 7.5% Inadequate or unavailable resources 5.2% Poorly communicated strategy 4.5% Actions required to execute not clearly defined 4.1% Unclear accountabilities for execution 3.7% Organizational silos and culture blocking execution 3.0% Inadequate performance monitoring 3.0% Inadequate consequences of rewards for failure or success 2.6% Poor senior leadership 1.9% Uncommitted leadership 0.7% Unapproved strategy 0.7% Other obstacles (including inadequate skills and capabilities) rately to close the gap, these companies work both sides nual bonuses) and top management pressing for more of the equation, raising standards for both planning long-term stretch (to satisfy the board of directors and and execution simultaneously and creating clear links other external constituents). Not surprisingly, the fore- between them. casts that emerge from these negotiations almost always Our research and experience in working with many of understate what each business unit can deliver in the near these companies suggests they follow seven rules that term and overstate what can realistically be expected in apply to planning and execution. Living by these rules the long-term-the hockey-stick charts with which CEOs enables them to objectively assess any performance short are all too familiar. fall and determine whether it stems from the strategy, Even at companies where the planning process is iso- the plan, the execution, or employees'capabilities. And the lated from the political concerns of performance evalu- same rules that allow them to spot problems early also ation and compensation, the approach used to generate help them prevent performance shortfalls in the first financial projections often has built-in biases. Indeed, fi- place. These rules may seem simple - even obvious - but nancial forecasting frequently takes place in complete iso- when strictly and collectively observed, they can trans- lation from the marketing or strategy functions. A busi- form both the quality of a company's strategy and its abil- ness unit's finance function prepares a highly detailed ity to deliver results. line-item forecast whose short-term assumptions may be Rule 1: Keep it simple, make it concrete. At most com- realistic, if conservative, but whose long-term assump- panies, strategy is a highly abstract concept - often con tions are largely uninformed. For example, revenue fore- fused with vision or aspiration - and is not something casts are typically based on crude estimates about average that can be easily communicated or translated into ac pricing, market growth, and market share. Projections of tion. But without a clear sense of where the company long-term costs and working capital requirements are is headed and why, lower levels in the organization can based on an assumption about annual productivity gains- not put in place executable plans. In short, the link be expediently tied, perhaps, to some companywide effi- tween strategy and performance can't be drawn because ciency program. These forecasts are difficult for top man- the strategy itself is not sufficiently concrete. agement to pick apart. Each line item may be completely To start off the planning and execution process on defensible, but the overall plan and projections embed the right track, high-performing companies avoid long, a clear upward bias-rendering them useless for driving drawn-out descriptions of lofty goals and instead stick strategy execution. to clear language describing their course of action. Bob High-performing companies view planning altogether Diamond, CEO of Barclays Capital, one of the fastest differently. They want their forecasts to drive the work growing and best-performing investment banking opera- they actually do. To make this possible, they have to en- tions in Europe, puts it this way: "We've been very clear sure that the assumptions underlying their long-term about what we will and will not do. We knew we weren't plans reflect both the real economics of their markets and going to go head-to-head with U.S. bulge bracket firms the performance experience of the company relative to We communicated that we wouldn't compete in this competitors. Tyco CEO Ed Breen, brought in to turn the way and that we wouldn't play in unprofitable segments company around in July 2002, credits a revamped plan- within the equity markets but instead would invest to building process for contributing to Tyco's dramatic re- position ourselves for the euro, the burgeoning need for covery. When Breen joined the company, Tyco was a fixed income, and the end of Glass-Steigel. By ensuring labyrinth of 42 business units and several hundred profit everyone knew the strategy and how it was different, centers, built up over many years through countless ac- we've been able to spend more time on tasks that are key quisitions. Few of Tyco's businesses had complete plans, to executing this strategy." and virtually none had reliable financial forecasts. By being clear about what the strategy is and isn't, com- To get a grip on the conglomerate's complex opera- panies like Barclays keep everyone headed in the same tions, Breen assigned cross-functional teams at each unit, direction. More important, they safeguard the perfor-drawn from strategy, marketing, and finance, to develop mance their counterparts lose to ineffective communica- detailed information on the profitability of Tyco's primary tions; their resource and action planning becomes more markets as well as the product or service offerings, costs, effective; and accountabilities are casier to specify. and price positioning relative to the competition. The Rule 2: Debate assumptions, not forecasts. At many teams met with corporate executives biweekly during companies, a business unit's strategic plan is little more Breen's first six months to review and discuss the findings. than a negotiated settlement-the result of careful bar- These discussions focused on the assumptions that would gaining with the corporate center over performance tar drive each unit's long-term financial performance, not on gets and financial forecasts. Planning, therefore, is largely the financial forecasts themselves. In fact, once assump- a political process - with unit management arguing for tions about market trends were agreed on, it was rela- lower near-term profit projections (to secure higher an- tively easy for Tyco's central finance function to prepare 69 JULY-AUGUST 2005 >> THE HIGH-PERFORMANCE ORGANIZATION externally oriented and internally consistent forecasts for work to link a business's performance in the product mar- each unit. kets with its financial performance over time, it is very Separating the process of building assumptions from difficult for top management to ascertain whether the that of preparing financial projections helps to ground financial projections that accompany a business unit's the business unit-corporate center dialogue in economic strategic plan are reasonable and realistically achievable. reality. Units can't hide behind specious details, and cor. As a result, management can't know with confidence porate center executives can't push for unrealistic goals. whether a performance shortfall stems from poor execu- What's more, the fact-based discussion resulting from this tion or an unrealistic and ungrounded plan. kind of approach builds trust between the top team and Rule 4: Discuss resource deployments early. Compa. each unit and removes barriers to fast and effective exe-nies can create more realistic forecasts and more exe- cution."When you understand the fundamentals and percutable plans if they discuss up front the level and timing formance drivers in a detailed way," says Bob Diamond, of critical resource deployments. At Cisco Systems, for "you can then step back, and you don't have to manage example, a cross-functional team reviews the level and the details. The team knows which issues it can get on timing of resource deployments early in the planning with, which it needs to flag to me, and which issues we stage. These teams regularly meet with John Chambers really need to work out together." (CEO), Dennis Powell (CFO), Randy Pond (VP of opera- Rule 3: Use a rigorous framework, speak a common lan- tions), and the other members of Cisco's executive team guage. To be productive, the dialogue between the cor- to discuss their findings and make recommendations. porate center and the business units about market trends Once agreement is reached on resource allocation and and assumptions must be conducted within a rigorous timing at the unit level, those elements are factored into framework. Many of the companies we advise use the the company's two-year plan. Cisco then monitors each concept of profit pools, which draws on the competition unit's actual resource deployments on a monthly basis (as theories of Michael Porter and others. In this framework, well as its performance) to make sure things are going a business's long-term financial performance is tied to the according to plan and that the plan is generating the total profit pool available in each of the markets it serves expected results. and its share of each profit pool-which, in turn, is tied to Challenging business units about when new resources the business's market share and relative profitability ver need to be in place focuses the planning dialogue on what sus competitors in each market. actually needs to happen across the company in order to In this approach, the first step is for the corporate cen- execute each unit's strategy. Critical questions invariably ter and the unit team to agree on the size and growth of surface, such as: How long will it take us to change cus- each profit pool. Fiercely competitive markets, such as tomers' purchase patters? How fast can we deploy our pulp and paper or commercial airlines, have small(or neg new sales force? How quickly will competitors respond? ative) total profit pools. Less competitive markets, like These are tough questions. But answering them makes soft drinks or pharmaceuticals, have large total profit the forecasts and the plans they accompany more feasible. pools. We find it helpful to estimate the size of each profit What's more, an early assessment of resource needs pool directly-through detailed benchmarking-and then also informs discussions about market trends and drivers, forecast changes in the pool's size and growth. Each busi improving the quality of the strategic plan and making it ness unit then assesses what share of the total profit pool far more executable. In the course of talking about the it can realistically capture over time, given its business resources needed to expand in the rapidly growing cable model and positioning Competitively advantaged busi- market, for example, Cisco came to realize that additional nesses can capture a large share of the profit pool - by growth would require more trained engineers to improve gaining or sustaining a high market share, generating existing products and develop new features. So, rather above-average profitability, or both. Competitively disad- than relying on the functions to provide these resources vantaged businesses, by contrast, typically capture a neg. from the bottom up, corporate management earmarked ligible share of the profit pool. Once the unit and the cor- a specific number of trained engineers to support growth porate center agree on the likely share of the pool the in cable. Cisco's financial planning organization carefully business will capture over time, the corporate center can monitors the engineering head count, the pace of feature easily create the financial projections that will serve as development, and revenues generated by the business to the unit's road map. make sure the strategy stays on track In our view, the specific framework a company uses to Rule 5: Clearly identify priorities. To deliver any strat- ground its strategic plans isn't all that important. What egy successfully, managers must make thousands of tacti- is critical is that the framework establish a common lan- cal decisions and put them into action. But not all tactics guage for the dialogue between the corporate center and are equally important. In most instances, a few key steps the units - one that the strategy, marketing, and finance must be taken - at the right time and in the right way- teams all understand and use. Without a rigorous frame to meet planned performance. Leading companies make a these priorities explicit so that each executive has a clear sense of where to direct his or her efforts. At Textron, a $10 billion multi- industrial conglomerate, each busi- ness unit identifies 'improvement priorities that it must act upon to realize the performance out- lined in its strategic plan. Each im- provement priority is translated into action items with clearly de- fined accountabilities, timetables, and key performance indicators (KPIS) that allow executives to tell how a unit is delivering on a prior- ity. Improvement priorities and action items cascade to every level at the company - from the man- agement committee (consisting of Textron's top five executives) down to the lowest levels in each of the company's ten business units. Lewis Campbell, Textron's CEO, summarizes the company's approach this way: "Everyone needs to know: 'If I have only one hour to work, here's what I'm going to focus on! Our goal de ployment process makes each in dividual's accountabilities and pri- orities clear." The Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche goes as far as to turn its business plans into detailed per- formance contracts that clearly specify the steps needed and the risks that must be managed to achieve the plans. These contracts all include a "delivery agenda" that lists the five to ten critical priorities with the greatest impact on performance. By maintaining a delivery agenda at each level of the company, Chairman and CEO Franz Humer and his leader ship team make sure "everyone at Roche understands exactly what we have agreed to do at a strategic level and that our strategy gets translated into clear execution pri- orities. Our delivery agenda helps us stay the course with the strat- egy decisions we have made so that execution is actually allowed to happen. We cannot control im- Turning Great Strategy into Great Performance plementation from HQ, but we can agree on the priorities, communi cate relentlessly, and hold managers accountable for executing against their commitments." Rule 6: Continuously monitor per- formance. Seasoned executives know almost instinctively whether a busi- ness has asked for too much, too lit- tle, or just enough resources to de- liver the goods. They develop this capability over time - essentially through trial and error. High-per- forming companies use real-time performance tracking to help accel- erate this trial-and-error process. They continuously monitor their resource deployment patterns and their results against plan, using continuous feedback to reset plan ning assumptions and reallocate re- sources. This real-time information allows management to spot and The prize for closing remedy flaws in the plan and short- falls in execution and to avoid con- the strategy-to- fusing one with the other. At Textron, for example, each KPI performance gap is carefully monitored, and regular is huge an increase operating reviews percolate per- formance shortfalls- or "red light" in performance of events - up through the manage- ment ranks. This provides CEO Lewis anywhere from 60% Campbell, CFO Ted French, and the to 100% for most other members of Textron's manage ment committee with the informa- companies. tion they need to spot and fix break- downs in execution. A similar approach has played an important role in the dramatic revival of Dow Chemical's fortunes. In December 2001, with perfor- mance in a free fall, Dow's board of directors asked Bill Stavropoulos (Dow's CEO from 1993 to 1999) to return to the helm. Stavropoulos and Andrew Liveris (the current CEO, then COO) immediately fo- cused Dow's entire top leadership team on execution through a proj- ect they called the Performance Improvement Drive. They began by defining clear performance met- rics for each of Dow's 79 business units. Performance on these key metrics was tracked against plans JULY AUGUST 2005 71 >> THE HIGH-PERFORMANCE ORGANIZATION on a weekly basis, and the entire leadership team dis- tocracy,""team,"and "integrity;"Barclays Capital has inno- cussed any serious discrepancies first thing every Mon- vative pay schemes that "ring fence" rewards. Stars don't day morning. As Liveris told us, the weekly monitoring lose out just because the business is entering new mar- sessions "forced everyone to live the details of execution" kets with lower returns during the growth phase. Says and let the entire organization know how we were Diamond: "It's so bad for the culture if you don't deliver performing." what you promised to people who have delivered... Continuous monitoring of performance is particularly You've got to make sure you are consistent and fair, unless important in highly volatile industries, where events out- you want to lose your most productive people." side anyone's control can render a plan irrelevant. Under Companies that are strong on execution also empha- CEO Alan Mulally, Boeing Commercial Airplanes' leader-size development. Soon after he became CEO of 3M, Jim ship team holds weekly business performance reviews to McNerney and his top team spent 18 months hashing out track the division's results against its multiyear plan. By a new leadership model for the company. Challenging de- tracking the deployment of resources as a leading indica bates among members of the top team led to agreement tor of whether a plan is being executed effectively, BCA's on six"leadership attributes"-namely, the ability to"chart leadership team can make course corrections each week the course;" "energize and inspire others" "demonstrate rather than waiting for quarterly results to roll in. ethics, integrity, and compliance," "deliver results," raise Furthermore, by proactively monitoring the primary the bar," and "innovate resourcefully." 3M's leadership drivers of performance (such as passenger traffic patterns, agreed that these six attributes were essential for the airline yields and load factors, and new aircraft orders), company to become skilled at execution and known for BCA is better able to develop and deploy effective coun- accountability. Today, the leaders credit this model with termeasures when events throw its plans off course. Dur- helping 3M to sustain and even improve its consistently ing the SARS epidemic in late 2002, for example, BCA's strong performance. leadership team took action to mitigate the adverse con- sequences of the illness on the business's operating plan The prize for closing the strategy-to-performance gap within a week of the initial outbreak. The abrupt decline is huge - an increase in performance of anywhere from in air traffic to Hong Kong, Singapore, and other Asian 60% to 100% for most companies. But this almost certainly business centers signaled that the number of future air- understates the true benefits. Companies that create craft deliveries to the region would fall-perhaps precipi- tight links between their strategies, their plans, and, ul- tously. Accordingly, BCA scaled back its medium-term pro- timately, their performance often experience a cultural duction plans (delaying the scheduled ramp-up of some multiplier effect. Over time, as they turn their strategies programs and accelerating the shutdown of others) and into great performance, leaders in these organizations adjusted its multiyear operating plan to reflect the antic- become much more confident in their own capabilities and ipated financial impact. much more willing to make the stretch commitments Rule 7: Reward and develop execution capabilities. No list that inspire and transform large companies. In turn, in- of rules on this topic would be complete without a re- dividual managers who keep their commitments are minder that companies have to motivate and develop rewarded with faster progression and fatter paychecks- their staffs; at the end of the day, no process can be better reinforcing the behaviors needed to drive any company than the people who have to make it work. Unsurpris forward. ingly, therefore, nearly all of the companies we studied Eventually, a culture of overperformance emerges. In insisted that the selection and development of manage- vestors start giving management the benefit of the doubt ment was an essential ingredient in their success. And when it comes to bold moves and performance delivery. while improving the capabilities of a company's work- The result is a performance premium on the company's force is no easy task - often taking many years - these ca- stock-one that further rewards stretch commitments and pabilities, once built, can drive superior planning and ex- performance delivery. Before long, the company's repu- ecution for decades. tation among potential recruits rises, and a virtuous circle For Barclays' Bob Diamond, nothing is more important is created in which talent begets performance, perfor- than "ensuring that the company] hires only A players." mance begets rewards, and rewards beget even more tal- In his view, "the hidden costs of bad hiring decisions are ent. In short, closing the strategy to performance gap is enormous, so despite the fact that we are doubling in size, not only a source of immediate performance improve- we insist that as a top team we take responsibility for all ment but also an important driver of cultural change with hiring. The jury of your peers is the toughest judgment, a large and lasting impact on the organization's capabili- so we vet each others' potential hires and challenge each ties, strategies, and competitiveness. other to keep raising the bar." It's equally important to make sure that talented hires are rewarded for superior Reprint RO507E; HBR On Point 1509