Question: Please read the attachment carefully. It is an example of an informal report. Please write the COVER EMAIL for this report. The word limit should

Please read the attachment carefully. It is an example of an informal report.

Please write the COVER EMAIL for this report. The word limit should be between 300 -350 words and follow the format.

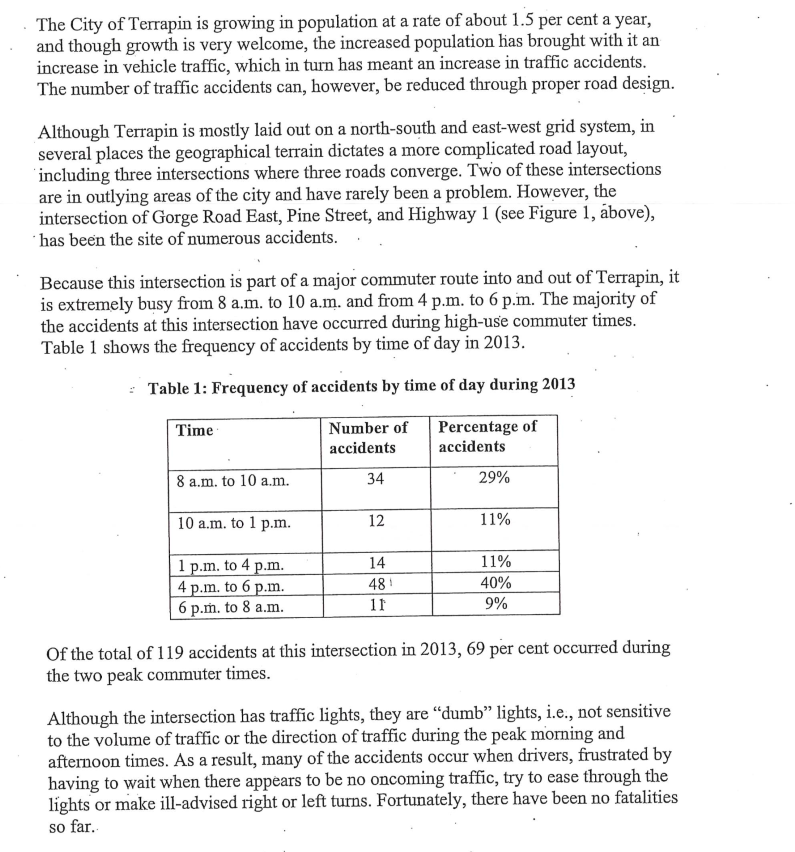

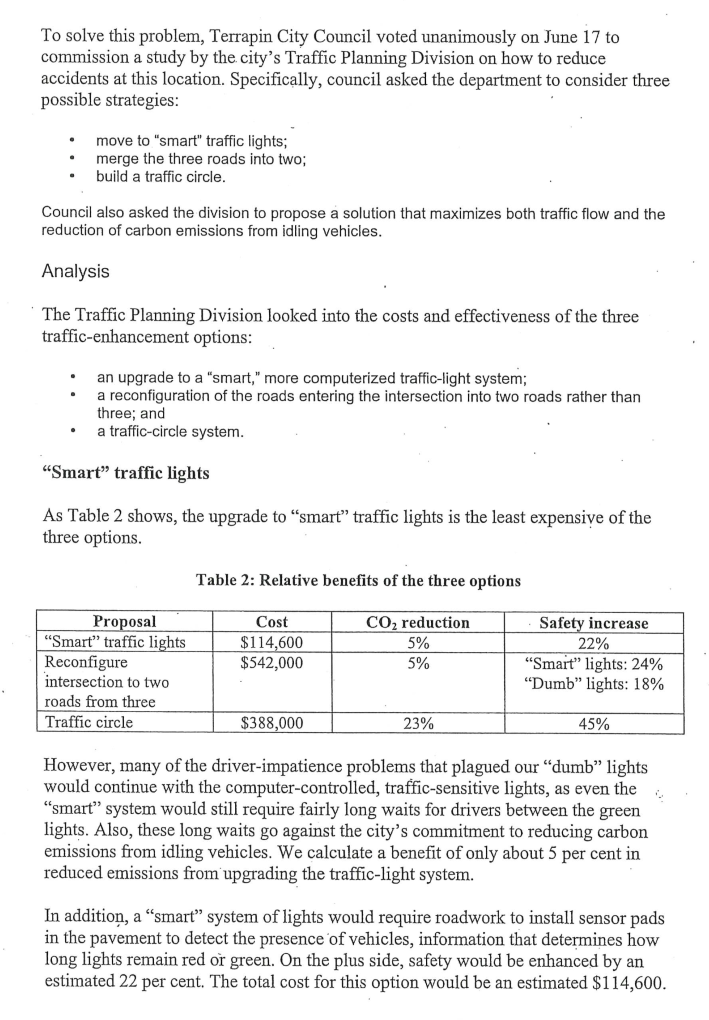

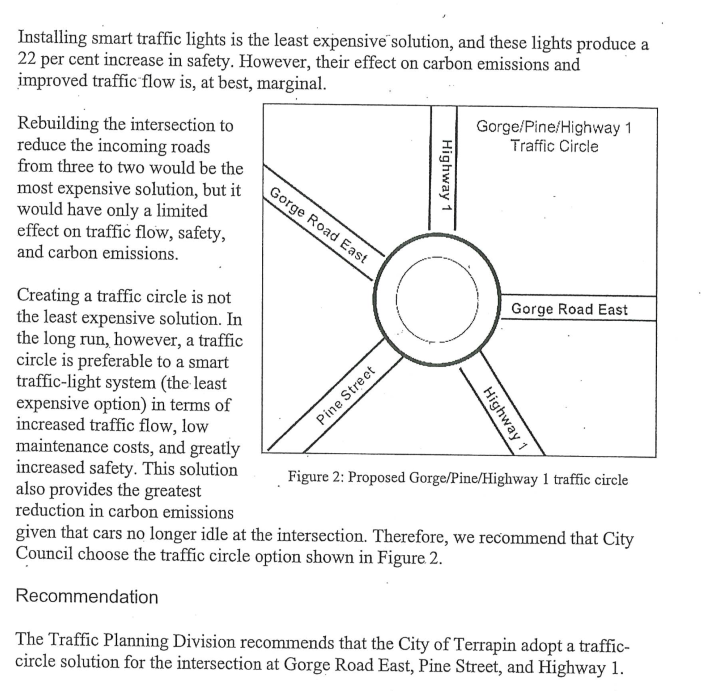

City of Terrapin 2331 Pinetree Road Terrapin, BC VOR 5T6. To: Christine Phelps, Mayor From: Mike Richards, Traffic Planning Division Date: October 24, 2014 Subject: Report on safer intersection at Gorge, Pine, and Highway 1 As requested by the Terrapin City Council in June, we are submitting the following report on a proposal to reduce accidents at the intersections of Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1. We look forward to your comments and are happy to answer questions on our report at the council's convenience. Summary Gorge/Pine/Highway 1 Intersection The intersection of Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1 has, for several years, been the city's most dangerous intersection, with an accident rate that, over the last five years, has been three times higher than that for any other location in Terrapin. The reason, in part, is that three roads converge at this intersection, making driver choices more complicated. In June, City Council asked the Terrapin Traffic Planning department to do a study and report on how to correct this problem. The department examined three possible solutions, while also taking into account the environmental impact of car exhaust emissions: installing computerized traffic Figure 1: Intersection of Gorge Road East, Pine, signals, reconfiguring the intersection to two and Highway 1 roads, and building a traffic circle. The department concluded that a traffic circle, while only the second most expensive solution, would be the safest and also the most carbon-neutral in terms of reducing emissions from idling vehicles. The City of Terrapin is growing in population at a rate of about 1.5 per cent a year, and though growth is very welcome, the increased population has brought with it an increase in vehicle traffic, which in turn has meant an increase in traffic accidents. The number of traffic accidents can, however, be reduced through proper road design. Although Terrapin is mostly laid out on a north-south and east-west grid system, in several places the geographical terrain dictates a more complicated road layout, including three intersections where three roads converge. Two of these intersections are in outlying areas of the city and have rarely been a problem. However, the intersection of Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1 (see Figure 1, above), has been the site of numerous accidents. Because this intersection is part of a major commuter route into and out of Terrapin, it is extremely busy from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. and from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. The majority of the accidents at this intersection have occurred during high-use commuter times. Table 1 shows the frequency of accidents by time of day in 2013. Table 1: Frequency of accidents by time of day during 2013 Time Number of accidents Percentage of accidents 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. 34 29% 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. 12 11% 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. 6 p.m. to 8 a.m. 14 48 11 11% 40% 9% Of the total of 119 accidents at this intersection in 2013, 69 per cent occurred during the two peak commuter times. Although the intersection has traffic lights, they are dumb lights, i.e., not sensitive to the volume of traffic or the direction of traffic during the peak morning and afternoon times. As a result, many of the accidents occur when drivers, frustrated by having to wait when there appears to be no oncoming traffic, try to ease through the lights or make ill-advised right or left turns. Fortunately, there have been no fatalities so far. To solve this problem, Terrapin City Council voted unanimously on June 17 to commission a study by the city's Traffic Planning Division on how to reduce accidents at this location. Specifically, council asked the department to consider three possible strategies: move to "smart" traffic lights; merge the three roads into two; build a traffic circle. Council also asked the division to propose a solution that maximizes both traffic flow and the reduction of carbon emissions from idling vehicles. Analysis The Traffic Planning Division looked into the costs and effectiveness of the three traffic-enhancement options: an upgrade to a "smart," more computerized traffic light system; a reconfiguration of the roads entering the intersection into two roads rather than three; and a traffic-circle system. Smart traffic lights As Table 2 shows, the upgrade to smart traffic lights is the least expensive of the three options. Table 2: Relative benefits of the three options Proposal "Smart" traffic lights Reconfigure intersection to two roads from three Traffic circle Cost $114,600 $542,000 CO2 reduction 5% 5% Safety increase 22% "Smart" lights: 24% "Dumb" lights: 18% $388,000 23% 45% However, many of the driver-impatience problems that plagued our "dumb" lights would continue with the computer-controlled, traffic-sensitive lights, as even the "smart" system would still require fairly long waits for drivers between the green lights. Also, these long waits go against the city's commitment to reducing carbon emissions from idling vehicles. We calculate a benefit of only about 5 per cent in reduced emissions from upgrading the traffic light system. In addition, a smart system of lights would require roadwork to install sensor pads in the pavement to detect the presence of vehicles, information that determines how long lights remain red or green. On the plus side, safety would be enhanced by an estimated 22 per cent. The total cost for this option would be an estimated $114,600. Reduction of converging roads Rebuilding the intersection to reduce the converging traffic to two streets from three is by far the most costly solution, at an estimated $542,000. As with the smart traffic light solution, there is very little benefit in terms of reduced carbon emissions (5 per cent). Although safety would improve when measured against the current system, the safety benefit will be no more than 18 per cent if we keep the "dumb" lights and 24 per cent with smart lights. Moreover, as part of the reconstruction work, council would probably also want to add smart traffic lights to the new intersection, with that additional cost. Traffic circle Though not the least expensive option at $388,000, a traffic circle offers several significant benefits. Drivers no longer have to wait for a light to change, which reduces frustration and therefore accidents. Carbon emissions from idling are decreased by an estimated 23 per cent-more than four times the amount achieved with the other two options. As well, traffic-circle studies in major cities in North America and Great Britain (where circles are called roundabouts) show that, for both large intersections and small, planners are increasingly adopting traffic circles to increase safety and reduce carbon emissions. The drawback of a traffic circle is a temporary learning curve as drivers get used to the etiquette of adapting to a new traffic pattern. However, evidence from other cities indicates the adaptation problems disappear after the first month or two. The city will also make some significant monetary savings in moving to a traffic- circle system. For one thing, traffic lights would no longer be necessary at all, with a considerable reduction in maintenance costs. And, of course, fewer accidents means a sizable saving in terms of the costs of police, fire, and ambulance call-outs. Conclusions The City of Terrapin is growing at a rate of about 1.5 per cent a year. With each year of growth, traffic increases. Each increase in traffic puts more pressure on the city's roads to be accident free, efficient in terms of moving vehicles, and environmentally friendly. In recent years, one location in particular has been a problem in terms of both accidents and the creation of traffic gridlock: the three-way intersection of Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1. At the request of Terrapin City Council, the Terrapin Traffic Planning Division prepared a report analyzing three possible solutions to the intersection's problems: smarter traffic lights, a reconfiguration of the intersection from three roads to two, or a traffic circle. The council also asked that, apart from safety, a smoother flow of traffic during rush hours and the reduction of carbon emissions be taken into consideration. Installing smart traffic lights is the least expensive solution, and these lights produce a 22 per cent increase in safety. However, their effect on carbon emissions and improved traffic flow is, at best, marginal. Gorge/Pine/Highway 1 Traffic Circle Rebuilding the intersection to reduce the incoming roads from three to two would be the most expensive solution, but it would have only a limited effect on traffic flow, safety, and carbon emissions. Highway 1 Gorge Road East Creating a traffic circle is not Gorge Road East the least expensive solution. In the long run, however, a traffic circle is preferable to a smart traffic-light system (the least expensive option) in terms of increased traffic flow, low maintenance costs, and greatly increased safety. This solution Figure 2: Proposed Gorge/Pine/Highway 1 traffic circle also provides the greatest reduction in carbon emissions given that cars no longer idle at the intersection. Therefore, we recommend that City Council choose the traffic circle option shown in Figure 2. Pine Street Highway 1 Recommendation The Traffic Planning Division recommends that the City of Terrapin adopt a traffic- circle solution for the intersection at Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1. City of Terrapin 2331 Pinetree Road Terrapin, BC VOR 5T6. To: Christine Phelps, Mayor From: Mike Richards, Traffic Planning Division Date: October 24, 2014 Subject: Report on safer intersection at Gorge, Pine, and Highway 1 As requested by the Terrapin City Council in June, we are submitting the following report on a proposal to reduce accidents at the intersections of Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1. We look forward to your comments and are happy to answer questions on our report at the council's convenience. Summary Gorge/Pine/Highway 1 Intersection The intersection of Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1 has, for several years, been the city's most dangerous intersection, with an accident rate that, over the last five years, has been three times higher than that for any other location in Terrapin. The reason, in part, is that three roads converge at this intersection, making driver choices more complicated. In June, City Council asked the Terrapin Traffic Planning department to do a study and report on how to correct this problem. The department examined three possible solutions, while also taking into account the environmental impact of car exhaust emissions: installing computerized traffic Figure 1: Intersection of Gorge Road East, Pine, signals, reconfiguring the intersection to two and Highway 1 roads, and building a traffic circle. The department concluded that a traffic circle, while only the second most expensive solution, would be the safest and also the most carbon-neutral in terms of reducing emissions from idling vehicles. The City of Terrapin is growing in population at a rate of about 1.5 per cent a year, and though growth is very welcome, the increased population has brought with it an increase in vehicle traffic, which in turn has meant an increase in traffic accidents. The number of traffic accidents can, however, be reduced through proper road design. Although Terrapin is mostly laid out on a north-south and east-west grid system, in several places the geographical terrain dictates a more complicated road layout, including three intersections where three roads converge. Two of these intersections are in outlying areas of the city and have rarely been a problem. However, the intersection of Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1 (see Figure 1, above), has been the site of numerous accidents. Because this intersection is part of a major commuter route into and out of Terrapin, it is extremely busy from 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. and from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. The majority of the accidents at this intersection have occurred during high-use commuter times. Table 1 shows the frequency of accidents by time of day in 2013. Table 1: Frequency of accidents by time of day during 2013 Time Number of accidents Percentage of accidents 8 a.m. to 10 a.m. 34 29% 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. 12 11% 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. 6 p.m. to 8 a.m. 14 48 11 11% 40% 9% Of the total of 119 accidents at this intersection in 2013, 69 per cent occurred during the two peak commuter times. Although the intersection has traffic lights, they are dumb lights, i.e., not sensitive to the volume of traffic or the direction of traffic during the peak morning and afternoon times. As a result, many of the accidents occur when drivers, frustrated by having to wait when there appears to be no oncoming traffic, try to ease through the lights or make ill-advised right or left turns. Fortunately, there have been no fatalities so far. To solve this problem, Terrapin City Council voted unanimously on June 17 to commission a study by the city's Traffic Planning Division on how to reduce accidents at this location. Specifically, council asked the department to consider three possible strategies: move to "smart" traffic lights; merge the three roads into two; build a traffic circle. Council also asked the division to propose a solution that maximizes both traffic flow and the reduction of carbon emissions from idling vehicles. Analysis The Traffic Planning Division looked into the costs and effectiveness of the three traffic-enhancement options: an upgrade to a "smart," more computerized traffic light system; a reconfiguration of the roads entering the intersection into two roads rather than three; and a traffic-circle system. Smart traffic lights As Table 2 shows, the upgrade to smart traffic lights is the least expensive of the three options. Table 2: Relative benefits of the three options Proposal "Smart" traffic lights Reconfigure intersection to two roads from three Traffic circle Cost $114,600 $542,000 CO2 reduction 5% 5% Safety increase 22% "Smart" lights: 24% "Dumb" lights: 18% $388,000 23% 45% However, many of the driver-impatience problems that plagued our "dumb" lights would continue with the computer-controlled, traffic-sensitive lights, as even the "smart" system would still require fairly long waits for drivers between the green lights. Also, these long waits go against the city's commitment to reducing carbon emissions from idling vehicles. We calculate a benefit of only about 5 per cent in reduced emissions from upgrading the traffic light system. In addition, a smart system of lights would require roadwork to install sensor pads in the pavement to detect the presence of vehicles, information that determines how long lights remain red or green. On the plus side, safety would be enhanced by an estimated 22 per cent. The total cost for this option would be an estimated $114,600. Reduction of converging roads Rebuilding the intersection to reduce the converging traffic to two streets from three is by far the most costly solution, at an estimated $542,000. As with the smart traffic light solution, there is very little benefit in terms of reduced carbon emissions (5 per cent). Although safety would improve when measured against the current system, the safety benefit will be no more than 18 per cent if we keep the "dumb" lights and 24 per cent with smart lights. Moreover, as part of the reconstruction work, council would probably also want to add smart traffic lights to the new intersection, with that additional cost. Traffic circle Though not the least expensive option at $388,000, a traffic circle offers several significant benefits. Drivers no longer have to wait for a light to change, which reduces frustration and therefore accidents. Carbon emissions from idling are decreased by an estimated 23 per cent-more than four times the amount achieved with the other two options. As well, traffic-circle studies in major cities in North America and Great Britain (where circles are called roundabouts) show that, for both large intersections and small, planners are increasingly adopting traffic circles to increase safety and reduce carbon emissions. The drawback of a traffic circle is a temporary learning curve as drivers get used to the etiquette of adapting to a new traffic pattern. However, evidence from other cities indicates the adaptation problems disappear after the first month or two. The city will also make some significant monetary savings in moving to a traffic- circle system. For one thing, traffic lights would no longer be necessary at all, with a considerable reduction in maintenance costs. And, of course, fewer accidents means a sizable saving in terms of the costs of police, fire, and ambulance call-outs. Conclusions The City of Terrapin is growing at a rate of about 1.5 per cent a year. With each year of growth, traffic increases. Each increase in traffic puts more pressure on the city's roads to be accident free, efficient in terms of moving vehicles, and environmentally friendly. In recent years, one location in particular has been a problem in terms of both accidents and the creation of traffic gridlock: the three-way intersection of Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1. At the request of Terrapin City Council, the Terrapin Traffic Planning Division prepared a report analyzing three possible solutions to the intersection's problems: smarter traffic lights, a reconfiguration of the intersection from three roads to two, or a traffic circle. The council also asked that, apart from safety, a smoother flow of traffic during rush hours and the reduction of carbon emissions be taken into consideration. Installing smart traffic lights is the least expensive solution, and these lights produce a 22 per cent increase in safety. However, their effect on carbon emissions and improved traffic flow is, at best, marginal. Gorge/Pine/Highway 1 Traffic Circle Rebuilding the intersection to reduce the incoming roads from three to two would be the most expensive solution, but it would have only a limited effect on traffic flow, safety, and carbon emissions. Highway 1 Gorge Road East Creating a traffic circle is not Gorge Road East the least expensive solution. In the long run, however, a traffic circle is preferable to a smart traffic-light system (the least expensive option) in terms of increased traffic flow, low maintenance costs, and greatly increased safety. This solution Figure 2: Proposed Gorge/Pine/Highway 1 traffic circle also provides the greatest reduction in carbon emissions given that cars no longer idle at the intersection. Therefore, we recommend that City Council choose the traffic circle option shown in Figure 2. Pine Street Highway 1 Recommendation The Traffic Planning Division recommends that the City of Terrapin adopt a traffic- circle solution for the intersection at Gorge Road East, Pine Street, and Highway 1Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock