Question: Please read the following two items in your textbook: (I have attached images of the pages) (1) Section 2.6 Practical Application: Encryption of Stored Data;

Please read the following two items in your textbook: (I have attached images of the pages) (1) Section 2.6 Practical Application: Encryption of Stored Data; (2) Section 3.8 Case Study: Security Problems for ATM systems.

Given the security issues/vulnerabilities described in the reading, what additional technical and/or managerial measures would you recommend to counter them (note: please do not include the ones that are already mentioned in the readings)?

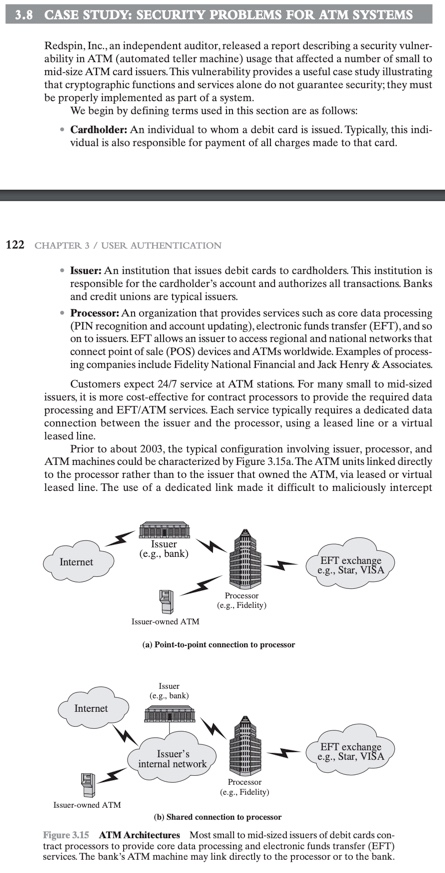

2.6 PRACTICAL APPLICATION: ENCRYPTION OF STORED DATA One of the principal security requirements of a computer system is the protection of stored data. Security mechanisms to provide such protection include access control, intrusion detection, and intrusion prevention schemes, all of which are discussed in this book. The book also describes a number of technical means by which these vari ous security mechanisms can be made vulnerable. But beyond technical approaches, these approaches can become vulnerable because of human factors. We list a few examples here, based on [ROTHOS): In December of 2004, Bank of America employees backed up then sent to its backup data center tapes containing the names, addresses, bank account num- bers, and Social Security numbers of 1.2 million government workers enrolled in a charge-card account. None of the data were encrypted. The tapes never arrived, and indeed have never been found. Sadly, this method of backing up and shipping data is all too common. As an another example, in April of 2005, Ameritrade blamed its shipping vendor for losing a backup tape containing unencrypted information on 200,000 clients In April of 2005, San Jose Medical group announced that someone had physi- cally stolen one of its computers and potentially gained access to 185,000 unen- crypted patient records There have been countless examples of laptops lost at airports, stolen from a parked car, or taken while the user is away from his or her desk. If the data on the laptop's hard drive are unencrypted, all of the data are available to the thief. Although it is now routine for businesses to provide a variety of protections, including encryption, for information that is transmitted across networks, via the Internet, or via wireless devices, once data are stored locally (referred to as data at rest), there is often little protection beyond domain authentication and operating system access controls.Data at rest are often routinely backed up to secondary stor- age such as optical media, tape or removable disk, archived for indefinite periods. Further, even when data are erased from a hard disk, until the relevant disk sectors 80 CHAPTER 2 / CRYPTOGRAPHIC TOOLS are reused, the data are recoverable. Thus, it becomes attractive, and indeed should be mandatory, to encrypt data at rest and combine this with an effective encryption key management scheme. There are a variety of ways to provide encryption services. A simple approach available for use on a laptop is to use a commercially available encryption package such as Pretty Good Privacy (PGP). PGP enables a user to generate a key from a password and then use that key to encrypt selected files on the hard disk. The PGP package does not store the password. To recover a file, the user enters the password, PGP generates the key, and then decrypts the file. So long as the user protects his or her password and does not use an easily guessable password, the files are fully protected while at rest. Some more recent approaches are listed in [COLL06): Back-end appliance: This is a hardware device that sits between servers and stor- age systems and encrypts all data going from the server to the storage system, and decrypts data going in the opposite direction. These devices encrypt data at close to wire speed, with very little latency. In contrast, encryption software on servers and storage systems slows backups. A system manager configures the appliance to accept requests from specified clients, for which unencrypted data are supplied. Library-based tape encryption: This is provided by means of a co-processor board embedded in the tape drive and tape library hardware. The co-processor encrypts data using a nonreadable key configured into the board. The tapes can then be sent off-site to a facility that has the same tape drive hardware. The key can be exported via secure e-mail, or a small flash drive that is transported securely. If the matching tape drive hardware co-processor is not available at the other site, the target facility can use the key in a software decryption pack- age to recover the data. Background laptop and PC data encryption: A number of vendors offer soft- ware products that provide encryption that is transparent to the application and the user. Some products encrypt all or designated files and folders. Other products, such as Windows BitLocker and MacOS File Vault, encrypt an entire disk or disk image located on either the user's hard drive or maintained on a network storage device, with all data on the virtual disk encrypted. Various key management solutions are offered to restrict access to the owner of the data. 3.8 CASE STUDY: SECURITY PROBLEMS FOR ATM SYSTEMS Redspin, Inc., an independent auditor, released a report describing a security vulner ability in ATM (automated teller machine) usage that affected a number of small to mid-size ATM card issuers. This vulnerability provides a useful case study illustrating that cryptographic functions and services alone do not guarantee security, they must be properly implemented as part of a system. We begin by defining terms used in this section are as follows: Cardholder: An individual to whom a debit card is issued. Typically, this indi- vidual is also responsible for payment of all charges made to that card. 122 CHAPTER 3/USER AUTHENTICATION Issuer: An institution that issues debit cards to cardholders. This institution is responsible for the cardholder's account and authorizes all transactions Banks and credit unions are typical issuers. Processor: An organization that provides services such as core data processing (PIN recognition and account updating), electronic funds transfer (EFT), and so on to issuers. EFT allows an issuer to access regional and national networks that connect point of sale (POS) devices and ATMs worldwide. Examples of process ing companies include Fidelity National Financial and Jack Henry & Associates Customers expect 24/7 service at ATM stations. For many small to mid-sized issuers, it is more cost-effective for contract processors to provide the required data processing and EFT/ATM services. Each service typically requires a dedicated data connection between the issuer and the processor, using a leased line or a virtual leased line. Prior to about 2003, the typical configuration involving issuer, processor, and ATM machines could be characterized by Figure 3.15a. The ATM units linked directly to the processor rather than to the issuer that owned the ATM, via leased or virtual leased line. The use of a dedicated link made it difficult to maliciously intercept Issuer (e.g., bank) Internet EFT exchange e... Star, VISA Process (es. Fidelity) Issur-owned ATM (a) Point-to-point connection to processor Issur e bank) Internet Issuer's internal network EFT exchange e.g., Star, VISA Processor (e... Fidelity) Issuer-owned ATM (b) Shared connection to processor Figure 3.15 ATM Architectures Most small to mid-sized issuers of debit cards con tract processors to provide core data processing and electronic funds transfer (EFT) services. The bank's ATM machine may link directly to the processor or to the bank. transferred data. To add to the security, the PIN portion of messages transmitted from ATM to processor was encrypted using DES (Data Encryption Standard). Proces- sors have connections to EFT (electronic funds transfer) exchange networks to allow cardholders access to accounts from any ATM. With the configuration of Figure 3.15a, a transaction proceeds as follows. A user swipes his or her card and enters his or her PIN. The ATM encrypts the PIN and transmits it to the processor as part of an autho- rization request. The processor updates the customer's information and sends a reply. In the early 2000s, banks worldwide began the process of migrating from an older generation of ATMs using IBM's OS/2 operating system to new systems run- ning Windows. The mass migration to Windows has been spurred by a number of factors, including IBM's decision to stop supporting OS/2 by 2006, market pressure from creditors such as MasterCard International and Visa International to introduce stronger Triple DES, and pressure from U.S. regulators to introduce new features for disabled users. Many banks, such as those audited by Redspin, included a number of other enhancements at the same time as the introduction of Windows and triple DES, especially the use of TCP/IP as a network transport. Because issuers typically run their own Internet connected local area networks (LAN) and intranets using TCP/IP, it was attractive to connect ATMs to these issuer networks and maintain only a single dedicated line to the processor, leading to the configuration illustrated in Figure 3.15b. This configuration saves the issuer expen- sive monthly circuit fees and enables easier management of ATMs by the issuer. In this configuration, the information sent from the ATM to the processor traverses the issuer's network before being sent to the processor. It is during this time on the issuer's network that the customer information is vulnerable. The security problem was that with the upgrade to a new ATM OS and a new communications configuration, the only security enhancement was the use of triple DES rather than DES to encrypt the PIN. The rest of the information in the ATM request message is sent in the clear. This includes the card number, expiration date, account balances, and withdrawal amounts. A hacker tapping into the bank's network, either from an internal location or from across the Internet potentially would have complete access to every single ATM transaction. The situation just described leads to two principal vulnerabilities: Confidentiality: The card number, expiration date, and account balance can be used for online purchases or to create a duplicate card for signature-based transactions Integrity: There is no protection to prevent an attacker from injecting or alter ing data in transit. If an adversary is able to capture messages en route, the adversary can masquerade as either the processor or the ATM. Acting as the processor, the adversary may be able to direct the ATM to dispense money without the processor ever knowing that a transaction has occurred. If an adver- sary captures a user's account information and encrypted PIN, the account is compromised until the ATM encryption key is changed, enabling the adversary to modify account balances or effect transfers. Redspin recommended a number of measures that banks can take to coun- ter these threats. Short-term fixes include segmenting ATM traffic from the rest of CHAPTER 3/USER AUTHENTICATION the network either by implementing strict firewall rule sets or physically dividing the networks altogether. An additional short-term fix is to implement network-level encryption between routers that the ATM traffic traverses. Long-term fixes involve changes in the application-level software. Protecting confidentiality requires encrypting all customer-related information that traverses the network. Ensuring data integrity requires better machine-to-machine authenti- cation between the ATM and processor and the use of challenge-response protocols to counter replay attacks. 2.6 PRACTICAL APPLICATION: ENCRYPTION OF STORED DATA One of the principal security requirements of a computer system is the protection of stored data. Security mechanisms to provide such protection include access control, intrusion detection, and intrusion prevention schemes, all of which are discussed in this book. The book also describes a number of technical means by which these vari ous security mechanisms can be made vulnerable. But beyond technical approaches, these approaches can become vulnerable because of human factors. We list a few examples here, based on [ROTHOS): In December of 2004, Bank of America employees backed up then sent to its backup data center tapes containing the names, addresses, bank account num- bers, and Social Security numbers of 1.2 million government workers enrolled in a charge-card account. None of the data were encrypted. The tapes never arrived, and indeed have never been found. Sadly, this method of backing up and shipping data is all too common. As an another example, in April of 2005, Ameritrade blamed its shipping vendor for losing a backup tape containing unencrypted information on 200,000 clients In April of 2005, San Jose Medical group announced that someone had physi- cally stolen one of its computers and potentially gained access to 185,000 unen- crypted patient records There have been countless examples of laptops lost at airports, stolen from a parked car, or taken while the user is away from his or her desk. If the data on the laptop's hard drive are unencrypted, all of the data are available to the thief. Although it is now routine for businesses to provide a variety of protections, including encryption, for information that is transmitted across networks, via the Internet, or via wireless devices, once data are stored locally (referred to as data at rest), there is often little protection beyond domain authentication and operating system access controls.Data at rest are often routinely backed up to secondary stor- age such as optical media, tape or removable disk, archived for indefinite periods. Further, even when data are erased from a hard disk, until the relevant disk sectors 80 CHAPTER 2 / CRYPTOGRAPHIC TOOLS are reused, the data are recoverable. Thus, it becomes attractive, and indeed should be mandatory, to encrypt data at rest and combine this with an effective encryption key management scheme. There are a variety of ways to provide encryption services. A simple approach available for use on a laptop is to use a commercially available encryption package such as Pretty Good Privacy (PGP). PGP enables a user to generate a key from a password and then use that key to encrypt selected files on the hard disk. The PGP package does not store the password. To recover a file, the user enters the password, PGP generates the key, and then decrypts the file. So long as the user protects his or her password and does not use an easily guessable password, the files are fully protected while at rest. Some more recent approaches are listed in [COLL06): Back-end appliance: This is a hardware device that sits between servers and stor- age systems and encrypts all data going from the server to the storage system, and decrypts data going in the opposite direction. These devices encrypt data at close to wire speed, with very little latency. In contrast, encryption software on servers and storage systems slows backups. A system manager configures the appliance to accept requests from specified clients, for which unencrypted data are supplied. Library-based tape encryption: This is provided by means of a co-processor board embedded in the tape drive and tape library hardware. The co-processor encrypts data using a nonreadable key configured into the board. The tapes can then be sent off-site to a facility that has the same tape drive hardware. The key can be exported via secure e-mail, or a small flash drive that is transported securely. If the matching tape drive hardware co-processor is not available at the other site, the target facility can use the key in a software decryption pack- age to recover the data. Background laptop and PC data encryption: A number of vendors offer soft- ware products that provide encryption that is transparent to the application and the user. Some products encrypt all or designated files and folders. Other products, such as Windows BitLocker and MacOS File Vault, encrypt an entire disk or disk image located on either the user's hard drive or maintained on a network storage device, with all data on the virtual disk encrypted. Various key management solutions are offered to restrict access to the owner of the data. 3.8 CASE STUDY: SECURITY PROBLEMS FOR ATM SYSTEMS Redspin, Inc., an independent auditor, released a report describing a security vulner ability in ATM (automated teller machine) usage that affected a number of small to mid-size ATM card issuers. This vulnerability provides a useful case study illustrating that cryptographic functions and services alone do not guarantee security, they must be properly implemented as part of a system. We begin by defining terms used in this section are as follows: Cardholder: An individual to whom a debit card is issued. Typically, this indi- vidual is also responsible for payment of all charges made to that card. 122 CHAPTER 3/USER AUTHENTICATION Issuer: An institution that issues debit cards to cardholders. This institution is responsible for the cardholder's account and authorizes all transactions Banks and credit unions are typical issuers. Processor: An organization that provides services such as core data processing (PIN recognition and account updating), electronic funds transfer (EFT), and so on to issuers. EFT allows an issuer to access regional and national networks that connect point of sale (POS) devices and ATMs worldwide. Examples of process ing companies include Fidelity National Financial and Jack Henry & Associates Customers expect 24/7 service at ATM stations. For many small to mid-sized issuers, it is more cost-effective for contract processors to provide the required data processing and EFT/ATM services. Each service typically requires a dedicated data connection between the issuer and the processor, using a leased line or a virtual leased line. Prior to about 2003, the typical configuration involving issuer, processor, and ATM machines could be characterized by Figure 3.15a. The ATM units linked directly to the processor rather than to the issuer that owned the ATM, via leased or virtual leased line. The use of a dedicated link made it difficult to maliciously intercept Issuer (e.g., bank) Internet EFT exchange e... Star, VISA Process (es. Fidelity) Issur-owned ATM (a) Point-to-point connection to processor Issur e bank) Internet Issuer's internal network EFT exchange e.g., Star, VISA Processor (e... Fidelity) Issuer-owned ATM (b) Shared connection to processor Figure 3.15 ATM Architectures Most small to mid-sized issuers of debit cards con tract processors to provide core data processing and electronic funds transfer (EFT) services. The bank's ATM machine may link directly to the processor or to the bank. transferred data. To add to the security, the PIN portion of messages transmitted from ATM to processor was encrypted using DES (Data Encryption Standard). Proces- sors have connections to EFT (electronic funds transfer) exchange networks to allow cardholders access to accounts from any ATM. With the configuration of Figure 3.15a, a transaction proceeds as follows. A user swipes his or her card and enters his or her PIN. The ATM encrypts the PIN and transmits it to the processor as part of an autho- rization request. The processor updates the customer's information and sends a reply. In the early 2000s, banks worldwide began the process of migrating from an older generation of ATMs using IBM's OS/2 operating system to new systems run- ning Windows. The mass migration to Windows has been spurred by a number of factors, including IBM's decision to stop supporting OS/2 by 2006, market pressure from creditors such as MasterCard International and Visa International to introduce stronger Triple DES, and pressure from U.S. regulators to introduce new features for disabled users. Many banks, such as those audited by Redspin, included a number of other enhancements at the same time as the introduction of Windows and triple DES, especially the use of TCP/IP as a network transport. Because issuers typically run their own Internet connected local area networks (LAN) and intranets using TCP/IP, it was attractive to connect ATMs to these issuer networks and maintain only a single dedicated line to the processor, leading to the configuration illustrated in Figure 3.15b. This configuration saves the issuer expen- sive monthly circuit fees and enables easier management of ATMs by the issuer. In this configuration, the information sent from the ATM to the processor traverses the issuer's network before being sent to the processor. It is during this time on the issuer's network that the customer information is vulnerable. The security problem was that with the upgrade to a new ATM OS and a new communications configuration, the only security enhancement was the use of triple DES rather than DES to encrypt the PIN. The rest of the information in the ATM request message is sent in the clear. This includes the card number, expiration date, account balances, and withdrawal amounts. A hacker tapping into the bank's network, either from an internal location or from across the Internet potentially would have complete access to every single ATM transaction. The situation just described leads to two principal vulnerabilities: Confidentiality: The card number, expiration date, and account balance can be used for online purchases or to create a duplicate card for signature-based transactions Integrity: There is no protection to prevent an attacker from injecting or alter ing data in transit. If an adversary is able to capture messages en route, the adversary can masquerade as either the processor or the ATM. Acting as the processor, the adversary may be able to direct the ATM to dispense money without the processor ever knowing that a transaction has occurred. If an adver- sary captures a user's account information and encrypted PIN, the account is compromised until the ATM encryption key is changed, enabling the adversary to modify account balances or effect transfers. Redspin recommended a number of measures that banks can take to coun- ter these threats. Short-term fixes include segmenting ATM traffic from the rest of CHAPTER 3/USER AUTHENTICATION the network either by implementing strict firewall rule sets or physically dividing the networks altogether. An additional short-term fix is to implement network-level encryption between routers that the ATM traffic traverses. Long-term fixes involve changes in the application-level software. Protecting confidentiality requires encrypting all customer-related information that traverses the network. Ensuring data integrity requires better machine-to-machine authenti- cation between the ATM and processor and the use of challenge-response protocols to counter replay attacks

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts