Question: Please read the question: What does the learning biography tell you about a student? 2 Laying the Groundwork for Biographic Biliteracy Profiles Thomas expressed confidence

Please read the question: What does the learning biography tell you about a student?

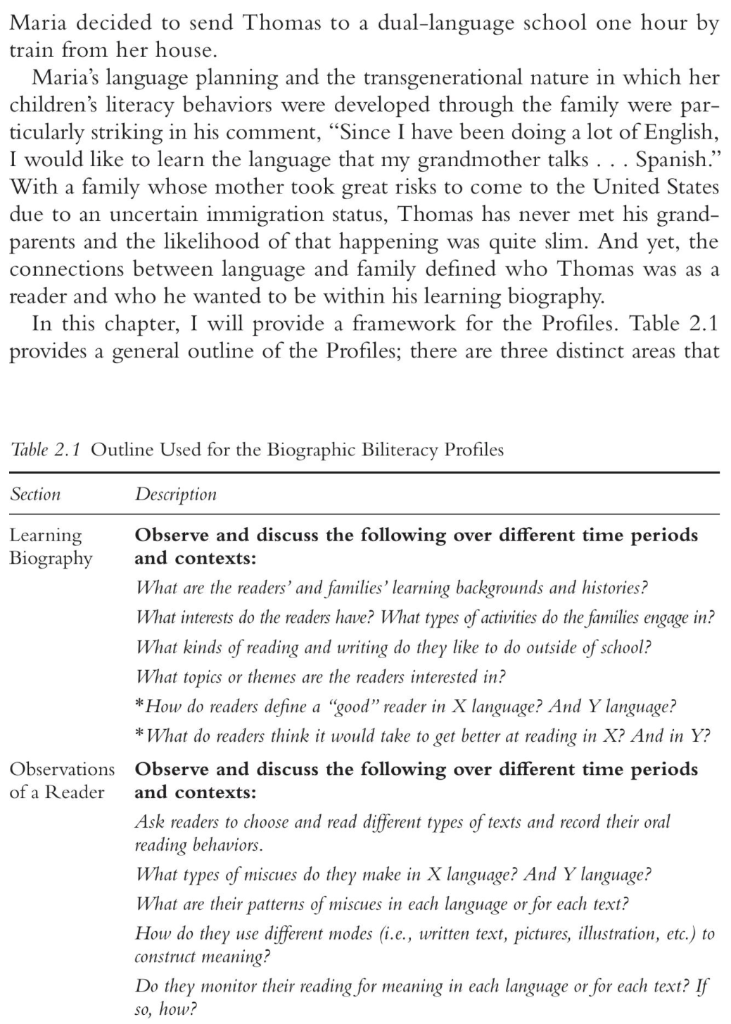

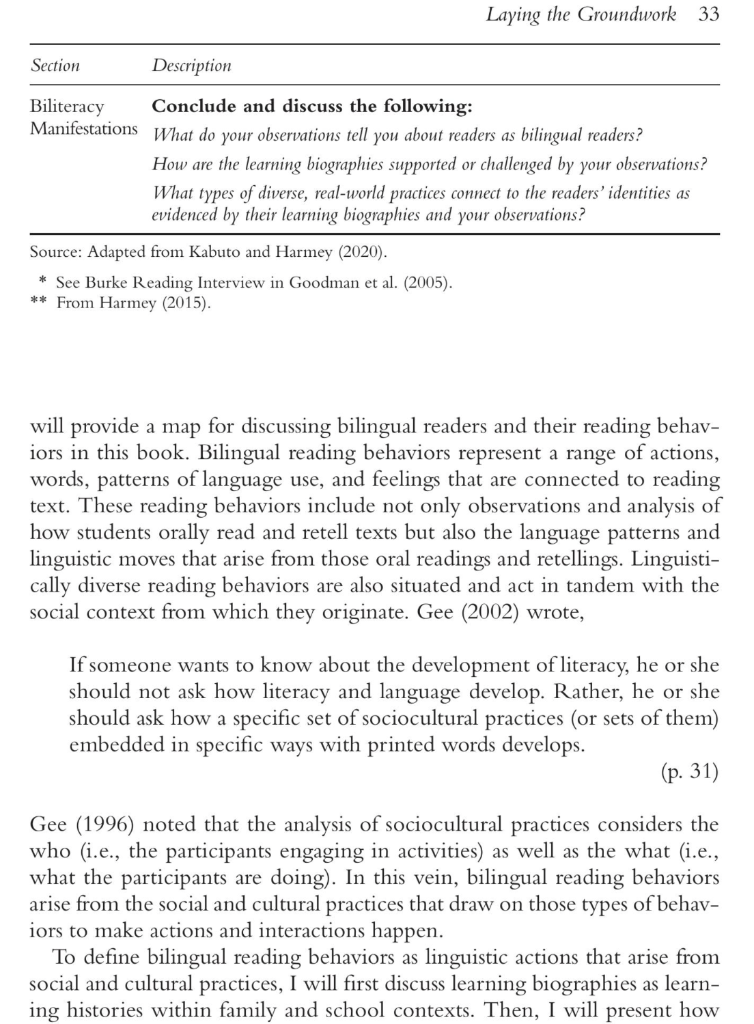

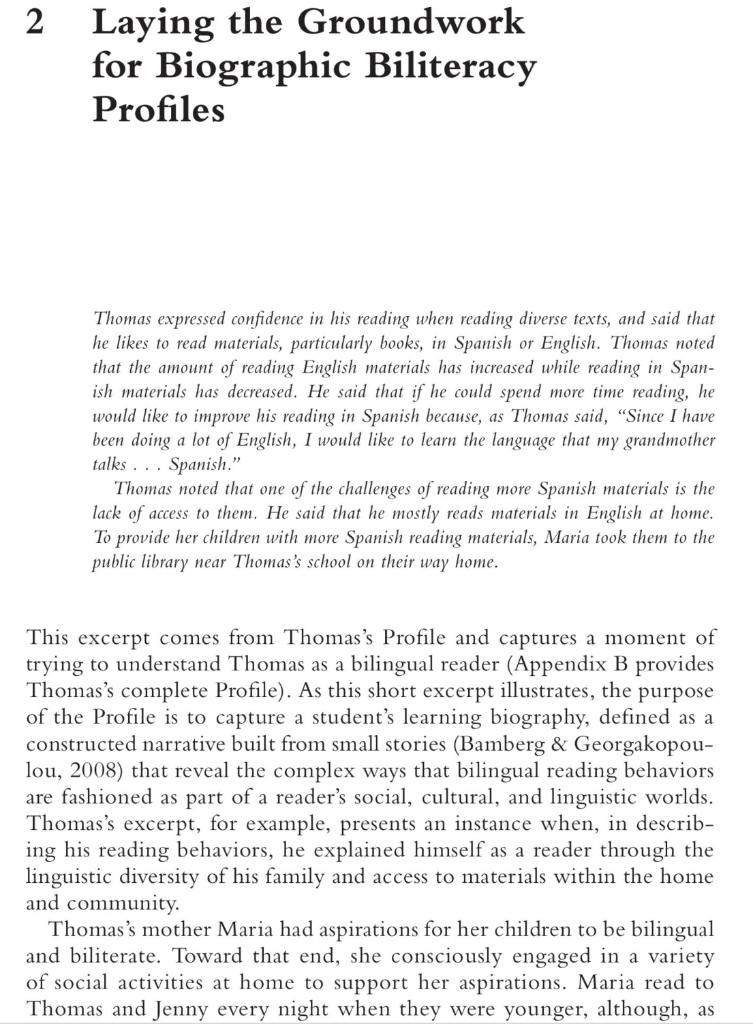

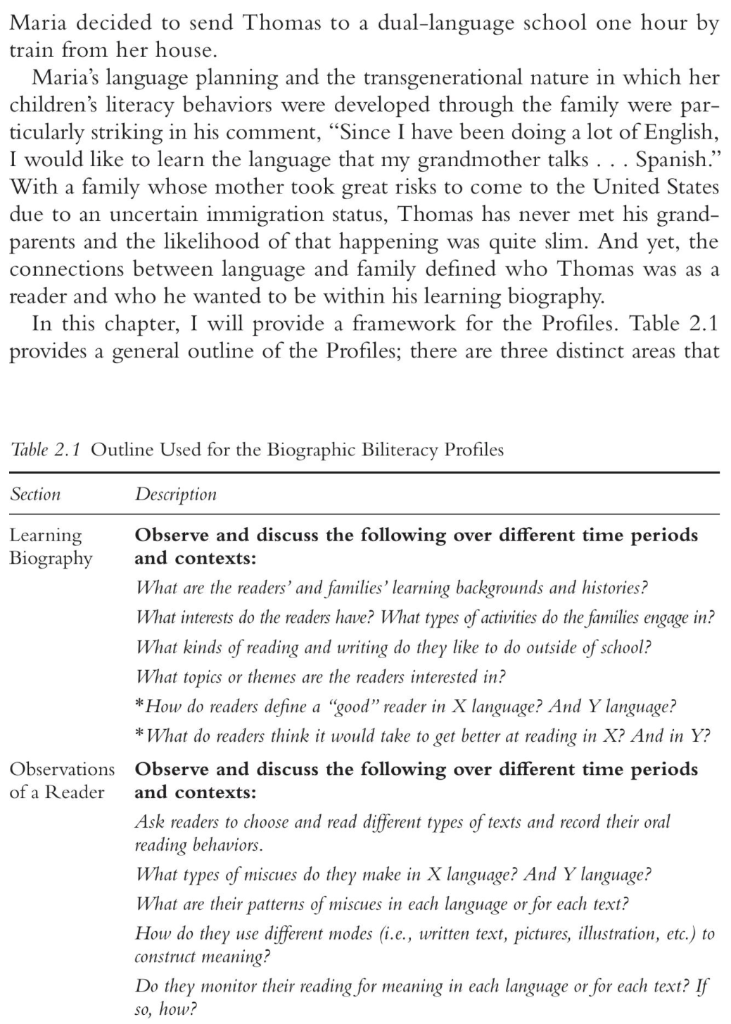

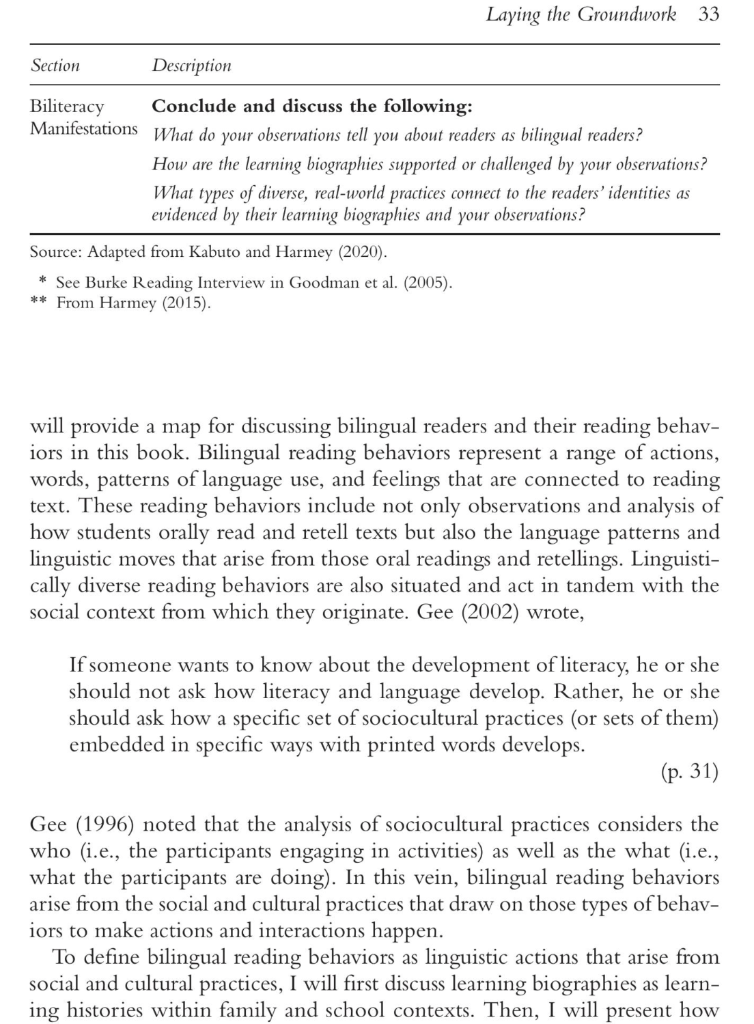

2 Laying the Groundwork for Biographic Biliteracy Profiles Thomas expressed confidence in his reading when reading diverse texts, and said that he likes to read materials, particularly books, in Spanish or English. Thomas noted that the amount of reading English materials has increased while reading in Spanish materials has decreased. He said that if he could spend more time reading, he would like to improve his reading in Spanish because, as Thomas said, "Since I have been doing a lot of English, I would like to learn the language that my grandmother talks. ... Spanish." Thomas noted that one of the challenges of reading more Spanish materials is the lack of access to them. He said that he mostly reads materials in English at home. To provide her children with more Spanish reading materials, Maria took them to the public library near Thomas's school on their way home. This excerpt comes from Thomas's Profile and captures a moment of trying to understand Thomas as a bilingual reader (Appendix B provides Thomas's complete Profile). As this short excerpt illustrates, the purpose of the Profile is to capture a student's learning biography, defined as a constructed narrative built from small stories (Bamberg \& Georgakopoulou, 2008) that reveal the complex ways that bilingual reading behaviors are fashioned as part of a reader's social, cultural, and linguistic worlds. Thomas's excerpt, for example, presents an instance when, in describing his reading behaviors, he explained himself as a reader through the linguistic diversity of his family and access to materials within the home and community. Thomas's mother Maria had aspirations for her children to be bilingual and biliterate. Toward that end, she consciously engaged in a variety of social activities at home to support her aspirations. Maria read to Thomas and Jenny every night when they were younger, although, as Maria noted, bedtime reading was not part of Ecuadorian culture. She, however, adopted the practice when Thomas's kindergarten teacher recommended it. Thomas said that his mother reading to him was important to him in learning how to read. When Thomas got older, he, in turn, read to his little sister Jenny. When it was time for Thomas to start school, Maria decided to send Thomas to a dual-language school one hour by train from her house. Maria's language planning and the transgenerational nature in which her children's literacy behaviors were developed through the family were particularly striking in his comment, "Since I have been doing a lot of English, I would like to learn the language that my grandmother talks . . . Spanish." With a family whose mother took great risks to come to the United States due to an uncertain immigration status, Thomas has never met his grandparents and the likelihood of that happening was quite slim. And yet, the connections between language and family defined who Thomas was as a reader and who he wanted to be within his learning biography. In this chapter, I will provide a framework for the Profiles. Table 2.1 provides a general outline of the Profiles; there are three distinct areas that Table 2.1 Outline Used for the Biographic Biliteracy Profiles How do they use discursive language practices to retell stories? Over time, observe and discuss the following: What behaviors did you notice? **Wh behaviors were new? **What has stayed the same? ** What is different? How do these behaviors support or challenge the reader's learning biography? Laying the Groundwork 33 Source: Adapted from Kabuto and Harmey (2020). * See Burke Reading Interview in Goodman et al. (2005). ** From Harmey (2015). will provide a map for discussing bilingual readers and their reading behaviors in this book. Bilingual reading behaviors represent a range of actions, words, patterns of language use, and feelings that are connected to reading text. These reading behaviors include not only observations and analysis of how students orally read and retell texts but also the language patterns and linguistic moves that arise from those oral readings and retellings. Linguistically diverse reading behaviors are also situated and act in tandem with the social context from which they originate. Gee (2002) wrote, If someone wants to know about the development of literacy, he or she should not ask how literacy and language develop. Rather, he or she should ask how a specific set of sociocultural practices (or sets of them) embedded in specific ways with printed words develops. (p. 31) Gee (1996) noted that the analysis of sociocultural practices considers the who (i.e., the participants engaging in activities) as well as the what (i.e., what the participants are doing). In this vein, bilingual reading behaviors arise from the social and cultural practices that draw on those types of behaviors to make actions and interactions happen. To define bilingual reading behaviors as linguistic actions that arise from social and cultural practices, I will first discuss learning biographies as learning histories within family and school contexts. Then, I will present how bilingual reading behaviors, as the observable act of orally reading and retelling text, are viewed from a socio-psycholinguistic perspective on reading. In particular, the addition of a translanguaging lens will add to the understanding of how reading as a language process is a unified process regardless of the forms that compose the named languages. Finally, I will discuss the last part of the Profile, biliteracy manifestations. This section will explore how linguistically diverse reading behaviors result from not only a social and cultural context but also a translanguaging context. 34 Laying the Groundwork Learning Biographies Within Profiles A biography involves telling a life story, whether our own through personal biographies or autobiographies or that of another. A learning biography, therefore, integrates students'learning histories, current learning trajectories, and future learning potentials into their life stories. Learning biographies provide glimpses into readers' identity enactments, or how one fashions and authors a sense of who they are in relation to other people, places, and things through the telling of stories and narratives (Coffey \& Street, 2008). Profiles are thus considered what Bakhtin termed dialogic, or multivoiced (Holquist, 1981), as the voices of two tellers come together: one the biographer's and the other is that of the subject of the biography. I will use the term biographer in this chapter as a neutral term to denote any individual (teacher, researcher, literacy coach, etc.) who may be engaged in the writing of a Profile. In this book, for instance, the Profiles represent partially my voice and perspectives as well as those I tried to capture and coordinate through various storylines that emerged from the data to create a larger narrative of what it means to be a bilingual reader in becoming biliterate. In this way, each Profile is unique and tells a distinct story of the teller, partly because, as Ochs and Capps (1996) remind us, "the tale ... lies beyond the telling." Thomas's symbolic connection to his grandmother, whom he had not yet had the opportunity to meet, exemplifies, in what may seem like a passing comment in a very brief moment, how deep insight into the social and emotional driving forces for language learning can come to the fore. In other words, the tale of Thomas's identity as a bilingual reader was intertwined with social and emotional factors embedded in his family's history. Thomas's statement about his grandmother took his thoughts and feelings and formed them into something real and tangible in how he saw himself in the context of his family. A biographer's role is to be a close observer who not only "captures a brief glimpse of the complexity of the symbol-weaving that takes place in the problem-solving situations as children reconstruct the functions, uses, and forms of written language" (Taylor in Kabuto, 2017, p. 90) but also takes on the role of an informed listener who documents how language serves multiple communicative functions to represent students' versions of their realities. Biographers organize narratives around past and present events with future possibilities. Narratives and Language In educational research, the term narrative is defined broadly to mean, on one end of spectrum, how one tells a story using story patterns and, at the other end of spectrum, the construction of larger patterns of meaning formed from socially situated actions and identity performances (Mishler, 1999). The former sees narratives and stories similarly while the latter views them differently. The learning biographies encountered in this book result from narratives that are constructed from storied realities based on students' experiences. Constructing narratives is a means of organizing and making sense of the multiple and varied experiences that result from the stories, large or small, that we tell (Cronon, 1992). Stories, on the other hand, are viewed as the oral and written storylines that individuals produce based on their experiences. Rogers (2004) used the term storied selves to describe how individuals develop understandings of themselves and their identities through stories. Bamberg and Georgakopoulou (2008) expanded this idea to describe "small stories" that are told in the fleeting moments of engaging in activities (p. 123). The idea of small stories plays a critical role in the development of narratives that inform the learning biographies in the Profiles. Thomas's statement about his grandmother is an example of a small story. In the time I spent with Thomas, he told other small stories like that of his three dogs, his exhaustion from taking the state tests, and reading to his sister Jenny at home. Bamberg and Georgakopoulou (2008) suggested that small stories live "on the fringes of narrative research" (p. 1). In the construction of learning biographies, biographers move these stories from the fringes to the heart of understanding the identity of linguistically diverse readers. This movement requires focusing on the "teller's representations of past events, and how the tellers make sense of themselves in light of these past events" (Bamberg \& Georgakopoulou, 2008, p. 1). Biographers do not just retell these stories - they connect the multiple storylines in various ways to form a narrative that challenges deficit-oriented perspectives of linguistic diversity that devalue certain types of language practices in home or school. The learning biographies that undergird the Profiles are the first step in creating culturally responsive ways to understand what students know and how that knowledge is directly or indirectly connected to readers' linguistic, social, and cultural experiences. Learning biographies situate learning experiences and reading behaviors within an asset-oriented narrative that brings their small stories into meaningful storylines connected to their social and cultural lives. Observations of a Reader: Defining Linguistically Thomas conducted six oral readings and retellings: one short story (Bored Tom), two Sports Illustrated for Kids articles, and three chapters in the book Yo, Naomi Leon (see Table 1.2). The oral readings and retellings occurred in a translanguaging context. In some sessions, Thomas read texts written in Spanish, like Yo, Noami Leon, and in English, like the articles from Sports Illustrated for Kids. In two of the three oral readings and retelling sessions for Yo, Noami Leon, Thomas retold the story in English. There were also sessions in which Thomas discussed his reading patterns and miscues for Yo, Naomi Leon, in English. When reading, 90% (or more) of the sentences Thomas read were grammatically acceptable. The semantic acceptability of his sentences (i.e., whether they made sense) ranged from 79% when reading Good as New to 99% when reading Chapter 3 of Yo, Naomi Leon. Thomas demonstrated an understanding of the texts that he read. After reading Small Wonder, for instance, Thomas described the story, saying: It was talking about what he [Messi] does when he plays soccer. He says what he does [and] about his childhood. When he was little and he practiced and that's why he's a professional football player. Every time he loses, he feels bad for himself. He doesn't scream or stufflike that. He also talks about how he gets prepared for the 2014 World Cup. When he read Chapter 3 of Yo, Naomi Leon, Thomas retold the chapter as: This chapter was about Naomi and Owen and the grandmother talking about Naomi's mother. Naomi noticed that the grandmother would worry about the mother. I think that the grandmother was worried because the mother might take Naomi and Owen away from her to a different place. Since the day that the mother came, the grandmother was not the same. She was different. Her attitude was different. In the Profiles, the observations of the readers attempt to capture a glimpse of readers' bilingual reading behaviors through close observations, documentation, and analysis of the readers' oral readings and retellings, as well as accompanying dialogue. Observing bilingual reading behaviors in this way is viewed through a socio-psycholinguistic perspective of reading. Coined and founded by Ken Goodman (1996), socio-psycholinguistic theory views reading as a constructive meaning-making process. The reading process is seen as a social process, in which readers draw from their language experiences, as well as a linguistic one. As a linguistic process, readers use language cueing systems (also described as linguistic cueing systems), defined as the syntactic (or grammatical), the semantic (or meaning), and the graphophonic systems. Finally, readers employ psycholinguistic strategies, also referred to as reading strategies, which are (a) initiate, sample, and select - the strategy that describes how readers focus on and select from information in the text (i.e., graphophonic, grammar, meaning, or picture); (b) predict and infer the strategy that describes how readers predict upcoming text and ideas; (c) confirm, disconfirm, and correct - the strategy that describes how readers confirm or disconfirm their predictions and correct them based on whether their predictions make sense; (d) integrate the strategy by which readers integrate predicted knowledge into their current schema; and (e) terminate the strategy by which readers select when and where to stop reading. Through socio-psycholinguistic theory, Goodman argued that miscues responses readers produce that differ from the written text are windows into the language cues and reading strategies that readers employ when they read. As Goodman suggested, while we cannot enter the heads of our readers, we can analyze readers' miscues to better understand how they transact with text using the reading process. To provide an illustration, consider the following sentence that Thomas read from Small Wonder (Ghosh, 2012): "I never really fixated on him or compared myself to another player" (p. 51). Thomas substituted to with the word with to read the sentence as, "I never really fixated on him or compared myself with another player." In this example, Thomas used the syntactic cueing system to substitute a word that maintained the grammatical structure of the sentence. At the same time, he used the semantic cueing system to produce a word that would make sense. In other words, the miscue substitution was grammatically acceptable and meaningful in the sentence. When considering psycholinguistic reading strategies, Thomas was most likely predicting based on grammar and his familiarity with language. When he read the sentence as, "I never really fixated on him or compared myself with another player," he confirmed that the sentence made sense, which caused him to continue reading during our reflective discussions of his miscue. Thomas exhibited a similar type of pattern when he read Yo, Naomi Leon (Ryan, 2005). When Thomas read the sentence, "Era el nino ms redondo de la escuela Buena Vista y uno de los ms simpticos" (He was the roundest child at Buena Vista school and one of the friendliest), he substituted el for un. Thomas's produced sentence read, "Era un nino ms redondo de la escuela Buena Vista y uno de los ms simpticos" (He was a rounder boy from Buena Vista school and one of the friendliest). In this example, Thomas used the grammatical cueing system to substitute el with un. Drawing from the semantic cueing system, Thomas created a substitution that would also make sense. Thomas was most likely predicting as he read and used the syntactic and semantic cueing systems to produce a miscue that was both grammatically acceptable and made sense. Because of this, Thomas confirmed his prediction. These two examples illustrate how viewing oral reading behaviors through socio-psycholinguistic theory suggests that reading is a process of active meaning construction as readers transact with the surface features of language to create a deeper meaning. The surface structure consists of the observable characteristics of written language, or the physical and measurable aspects (Smith, 2012). In both examples, Thomas attended to the graphic features of both texts. He, however, used them in an efficient manner as he constructed a deeper meaning of the text (Smith, 2012). This deep meaning cannot be directly measured or observed and was what guided Thomas's understanding, allowing him to make meaningful predictions based on his knowledge of grammar and meaningful sentence structures. In other words, when Thomas made the word substitutions (with for t and un for el ), he was predicting based on grammar and meaning and did not necessarily need to overly focus on the graphic features. Reading as a Unified Language Process The research on translanguaging adds another dimension to understanding bilingual reading behaviors. Translanguaging views language as a unified linguistic repertoire (Garcia \& Wei, 2014). Connecting this view of language from a socio-psycholinguistic perspective to the study of linguistically diverse reading behaviors highlights how reading is a universal process, or a unified language process. Goodman (1996) wrote about the universality of reading, "In spite of the diversity within, reading is a universal process, a single way of making sense of written language" (p. 9). In other words, regardless of the syntactic and semantic features and graphic forms that make up written language systems, readers draw upon a range of linguistic features within a language or across languages to demonstrate their understandings of and construct meaning with written text. Taking this perspective suggests that bilingual reading behaviors are not just the interaction and influence of one linguistic system, say Spanish, with another linguistic system, like English. Deep meaning is not necessarily observable, tangible, and translatable through the surface features of named languages. Evidence of this came from Thomas's retellings and the reflective discussions of his miscues. In the opening section, I presented Thomas's retelling of Chapter 3 of Yo, Naomi Leon. Thomas read aloud Chapter 3 of the book, which was written in Spanish. After he read, Livia asked him to retell the chapter, which he did in English. This retelling discussion resulted: "So tell me, what was this all about?," Livia asked. Thomas said, "This chapter was about Naomi and Owen and the grandmother talking about Naomi's mother. Naomi noticed that the grandmother would worry about the mother." "And why do you think the grandmother was worried?" "I think that the grandmother was worried because the mother might take Naomi and Owen away from her to a different place," Thomas replied. Livia asked, "Ok, did it say that in the chapter?" "No." Livia added, "But you are thinking that that might happen. Do you think that the kids were worried? What do you think the kids were thinking?" Thomas responded, "I think Naomi was worried, but Owen not that much." "Why do you think that Naomi thought it was strange for her grandmother to behave the way she was behaving?" "Because since the day that the mother came, the grandmother was not the same. She was different. Her attitude was different," Thomas explained. "And what happened at the end that was so catastrophic?," Livia asked. "They were going to miss an episode of Wheel of Fortune." "How many episodes had they watched all together? Thomas said, "In total, 743 ." Thomas provided a retelling that demonstrated his understanding of the chapter. His retelling included details, like the number of episodes of Wheel of Fortune that Naomi and her grandmother had watched together and a discussion of the overall character changes that Naomi saw in her grandmother. Notably, the language of the text and the retelling, while taking different linguistic forms, did not result in barriers to Thomas's ability to demonstrate his understanding of the text. The fluidity of the language context supported a translanguaging perspective so that bilinguals are not balancing two separate linguistic systems. Rather, bilingual readers like Thomas draw on a range of language forms for communicative and meaningful purposes to transact not only with the text but also with others who participate in the reading context. This type of dynamic language behavior was also evident in our reflective discussions about Thomas's miscues. During one of our sessions, Thomas read the sentence from Yo, Naomi Leon (Ryan, 2005), "Naomi fue a un psiclogo durante dos aos" [Naomi went to a psychologist for two years] (p. 25) as "Naomi fue a una psicloga durante dos aos." Thomas substituted the feminine for the masculine form of the word psychologist (un/a psiclogo/a). During one of our reflective conversations on whether Thomas's miscues made sense, Livia showed him the substitution and the following dialogue emerged: Livia said, "Did you hear what you did? What did you do?" Thomas replied, "I said una psicloga." [a female psychologist] Livia clarified how the text should read, "And what is it?" "Un psiclogo." [a male psychologist] Livia turned to Maria and said in Spanish, "Thomas said psychologist (feminine form), but its psychologist (masculine form). He did the same thing three times." Livia said to Thomas in English, "Three times, Thomas, you did the same thing. So why do you think you did that?" "I'm not sure." "Because when I asked you to read it, you said una psicloga a psychologist (female)," Livia said. "Then I asked you to read it again and you said una psicloga - a psychologist. Then, when you heard it, I don't think you caught it. Did you catch it when you heard it [on the tape]?" "No." Livia asked, "Do you think that it makes a difference whether you say una psicloga [female psychologist], or un psiclogo [male psychologist]?" "No, not really. The only difference is that they change the O and the A [for feminine and masculine]," Thomas replied. "It says that the girl visited a psychologist." Thomas explained, "I was thinking that the psychologist is a woman and not a man." In this example, Thomas, Livia, and Maria discussed Thomas's miscue and the written text within a dynamic language context as they moved between the written language of the text and the spoken languages of the participants. In this one particular collaborative discussion, Thomas discussed how his miscue was the result of a change in graphic information, but the change did not inherently disrupt the meaning that Thomas constructed as he read. Thomas predicted that the psychologist was a woman, which then caused him to read the feminine form of the word. These examples illustrate how translanguaging is not just the language norm it also provides a context, or space (Wei, 2011), for Thomas, Maria, and Livia to generate shared knowledge of each other as bilingual readers. The context, while made up of people and things, maintained a dynamic state through language fluidity, as defined from a translanguaging perspective. In order for there to be a translanguaging context, a variety of linguistic forms must be present from which participants may freely select. For instance, even within the fluidity of the language context, Thomas talked about "Spanish" and "English" forms. For Thomas, these forms were not without value and meaning. The selection of linguistic forms and movement among them can be viewed from a code-switching perspective, which I will take the liberty to redefine as moving among a range of linguistic resources, including but not limited to linguistic oral and written forms and meaning and semiotic systems. Bypassing a definition of code-switching that limits its understanding to switching among codes as isolated linguistic units, which some researchers support and advocate, means recentering meaning at the heart of why individuals may draw from a range of linguistic resources within a translanguaging context. Pennycook (2010) argued, "Issues of language diversity will be crucial, especially if we attempt to step away from a view of diversity in terms of enumerating languages, and instead focus on diversity of meaning. The ways in which languages can be understood multimodally, as working in different modes in different domains, will also be significant" (p. 3). These ideas will be further explored in more detail in Chapter 4. iliteracy Manifestations Within a ranslanguaging Context The construction of Thomas's Profile resulted from interviews with Thomas, oral reading, and retelling events with diverse texts, and reflective and collaborative discussions of Thomas's miscues. These artifacts, or manifestations, illustrate the complex ways that his reading behaviors were part and parcel of the linguistic diversity of the family, school and local contexts within which reading was situated. At the beginning of the sessions, Thomas expressed his confidence in reading diverse texts and within contexts that lacked language barriers and differentiation. The reading data from the miscue analyses support that Thomas was not only comfortable in orally reading and retelling texts presented to him. He was also reflective on his miscues when reading diverse texts, why he made them, and how the discussions changed him as a reader. In the process of reading diverse texts, Thomas enacted effective bilingual reading behaviors and was reflective of himself as a linguistically diverse reader. When asked about reading the diverse texts that were part of the reflective conversations, Thomas responded that he did not feel that he did anything different when reading texts written in Spanish and English. Thomas said, "When I read in English or in Spanish, if I make a mistake I go back to the sentence and make sure that the sentence makes sense." The concept of biliteracy manifestations draws from the work of Whitmore and Meyer (2020) to describe the "demonstrations of meaning making," or 'stuff,' that arise out of the meaning-making process, including but not limited to reading and writing and learners' thought processes. Literacy manifestations are affective, situated in sociocultural and linguistic contexts, and sensitive to time (Whitmore \& Meyer, 2020). As discussed in the previous excerpt, reading, as a demonstration of meaning construction, manifested itself within family and school practices. For Thomas, being a bilingual reader was just as much about connecting to the text as it was about bonding with family to recreate in-the-moment feelings and connections to reading. In other words, Thomas's bilingual reading behaviors had a symbolic and local aspect as they were also rooted in his family and the actual and imagined (like his grandmother) shared histories. Literacy manifestations, therefore, are the evidence of reading events and practices that are connected to home and school contexts, diverse places, and people. These manifestations resulted from Thomas's identity enactments, or how he used language to create a self-in-practice. This self-in-practice was only possible because it was embedded in the sociocultural and linguistic contexts framed by translanguaging. By "context," I refer to a general definition of shared spaces, places, and locations. Through this definition, context can be demarcated by certain physical boundaries and locations, like a school building, or it can be fluid, dynamic open spaces defined by the people and things in that shared space. broadest sense, and classrooms as physical and metaphorical borders that privilege certain ways of using language and demonstrating knowledge. When students are removed from the physical boundaries of schools and observed in their home or work contexts, what they know and how they communicate that knowledge suddenly changes (Gonzalez et al., 2005). Students who have been seen as underachieving were then perceived as knowledgeable experts in a context outside of school. A more nuanced and multifaceted definition of context needs to be considered. This definition draws from the dialogical and constructive nature of context in that there are not only people, things, and ways of acting and being that help to define the context. There are also unseen aspects that can influence and often undergird how individuals within that shared space act and participate in practice. These unseen social processes connect to ideologies, status, and power relations, which can privilege or limit particular ways of acting and being in any context. For linguistically diverse students, as illustrated in Thomas's Profile, their literacy manifestations are often constructed within a translanguaging context. Similar to any context, a translanguaging context is conceptualized and realized through social activities and processes. In addition, whether the context refers to a classroom, church, restaurant, or store, language plays a role in organizing activities. As such, researchers suggest that we need to move away from thinking of language as a closed structure and system to one of doing, or languaging (Pennycook, 2010). Unique to itself, a translanguaging context allows for the fluidity of language use, or as Pennycook described, the remaking of language. Pennycook (2010) explained, "We remake the language and the space in which this happens." (p. 2). How language forms are used, come together, negotiated, valued, and sometimes devalued are the result of how individuals or groups of individuals interpret the translanguaging context. At the same time, how individuals respond and use language to engage in activity reinforces how they identify the context. For instance, Thomas was able to use translanguaging practices because the context, defined by the materials (like books) and people (like Maria, Livia, and me), supported and valued the practice. In turn, as Thomas interpreted each session, reading event, and collaborative discussion over time, translanguaging then reinforced the context in which those social activities were embedded. The result was that Thomas was able to demonstrate and articulate his sense making and thought processes and produce artifacts that are windows into literacy identities (Whitmore \& Meyer, 2020). Identity is a concept built on collective aspects of personal and social selves (Hannover \& Zander, 2020; Silseth \& Arnseth, 2011). Identity is thus lived through and located within social practices, as much as it is a product of a translanguaging context for linguistically diverse readers. In Chapter 5, I will conceptualize identity through two interrelated concepts - the self-in-action and the sense-of-self - and discuss how these two interrelated views inform the process of becoming not just a bilingual reader but also in becoming biliterate. Concluding Thoughts Through the concept of learning biographies, observations of readers, and biliteracy manifestations, the Profiles illustrate the complexity of becoming biliterate. The Profiles provide an integrative and interdisciplinary means of understanding the connections between identity, becoming a bilingual reader, and biliteracy. The subsequent chapters focus more on the examination of the translanguaging context of the readers in this book. In Chapter 3 , we will meet Mai and Sophie to study the reading process as a unified process for reading texts written in other written language systems. Chapter 3 also takes a closer look at the miscues and comprehension of these two readers within a translanguaging context. Chapters 3 through 5 conclude with lessons learned from the themes that connect the Profiles