Question: Please write in JAVA HERE IS THE TEST CODE: import static org.junit.Assert.*; import org.junit.After; import org.junit.Before; import org.junit.Test; import java.math.BigInteger; import java.util.*; import java.util.zip.CRC32; public

Please write in JAVA

HERE IS THE TEST CODE:

HERE IS THE TEST CODE:

| import static org.junit.Assert.*; | |

| import org.junit.After; | |

| import org.junit.Before; | |

| import org.junit.Test; | |

| import java.math.BigInteger; | |

| import java.util.*; | |

| import java.util.zip.CRC32; | |

| public class CoinMoveTest { | |

| @Test public void testCoinMove() { | |

| Random rng = new Random(12345); | |

| CRC32 check = new CRC32(); | |

List

| |

| for(int i = 0; i | |

| int n = rng.nextInt(i / 3 + 2) + 2; | |

| int c = rng.nextInt(3 * n + 3) + 2; | |

| int[] curr = new int[n]; | |

| int[] next = new int[n]; | |

| nbs.clear(); | |

| // Create random neighbours for each position | |

| for(int j = 0; j | |

| ArrayList | |

| while(rng.nextDouble() | |

| int nn = rng.nextInt(n); | |

| if(nn == j) { nn = (nn + 1) % n; } | |

| nb.add(nn); | |

| } | |

| nbs.add(nb); | |

| } | |

| // Initialize coins in each position | |

| for(int j = 0; j | |

| curr[rng.nextInt(n)]++; | |

| } | |

| //System.out.println(nbs); | |

| //System.out.println(Arrays.toString(curr)); | |

| CoinMove.coinStep(curr, next, nbs); | |

| //System.out.println(Arrays.toString(next)); | |

| //System.out.println(""); | |

| check.update(Arrays.toString(next).getBytes()); | |

| } | |

| assertEquals(2310893907L, check.getValue()); | |

| } | |

| @Test public void testPeriod() { | |

| Random rng = new Random(7777); | |

| CRC32 check = new CRC32(); | |

List

| |

| for(int i = 0; i | |

| int n = rng.nextInt(15) + 2; | |

| int c = rng.nextInt(3 * n + 3) + 2; | |

| int[] curr = new int[n]; | |

| nbs.clear(); | |

| // Create random neighbours for each position | |

| for(int j = 0; j | |

| ArrayList | |

| while(nb.size() == 0 || rng.nextDouble() | |

| int nn = rng.nextInt(n); | |

| if(nn == j) { nn = (nn + 1) % n; } | |

| nb.add(nn); | |

| } | |

| nbs.add(nb); | |

| } | |

| // Initialize coins in each position | |

| for(int j = 0; j | |

| curr[rng.nextInt(n)]++; | |

| } | |

| //System.out.println(nbs); | |

| //System.out.println(Arrays.toString(curr)); | |

| int result = CoinMove.period(curr, nbs); | |

| //System.out.println(result); | |

| check.update(result); | |

| } | |

| assertEquals(1281024593L, check.getValue()); | |

| } | |

| } |

make sure the code can pass the test, will give up the vote. Thanks

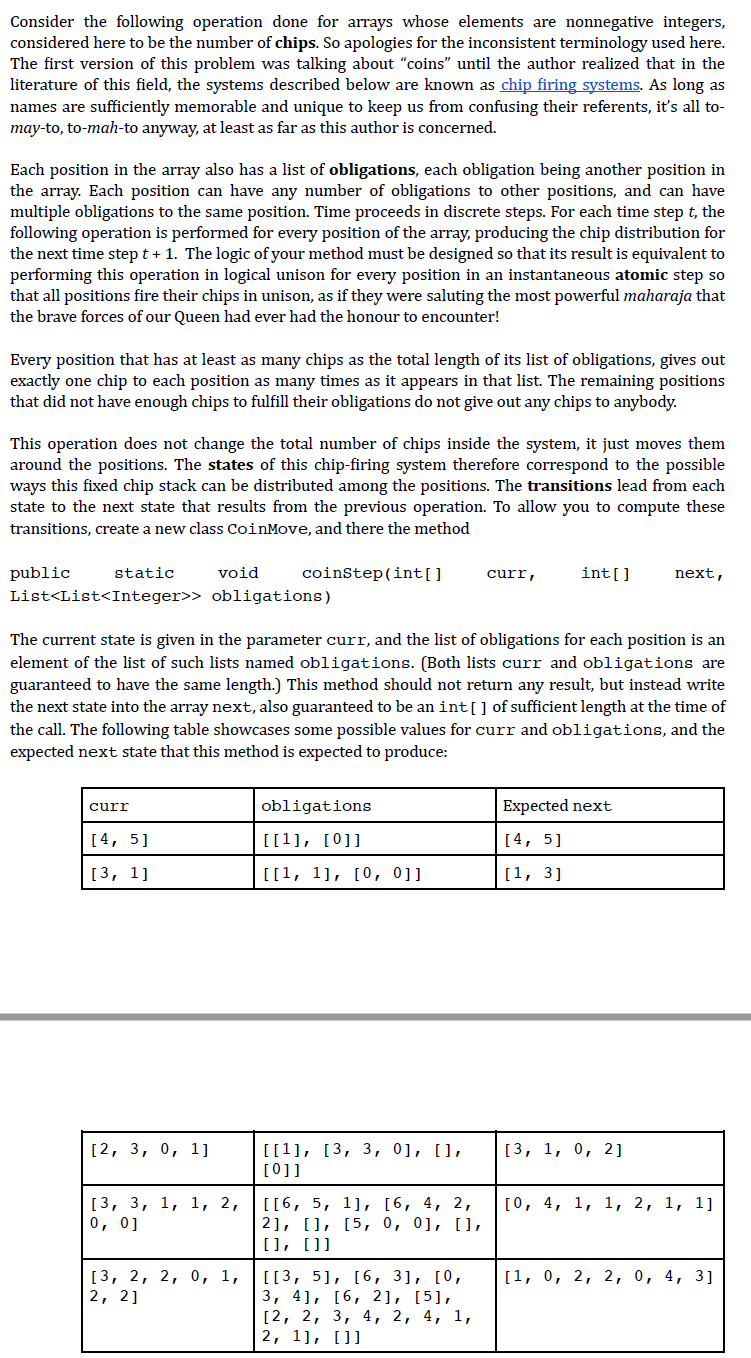

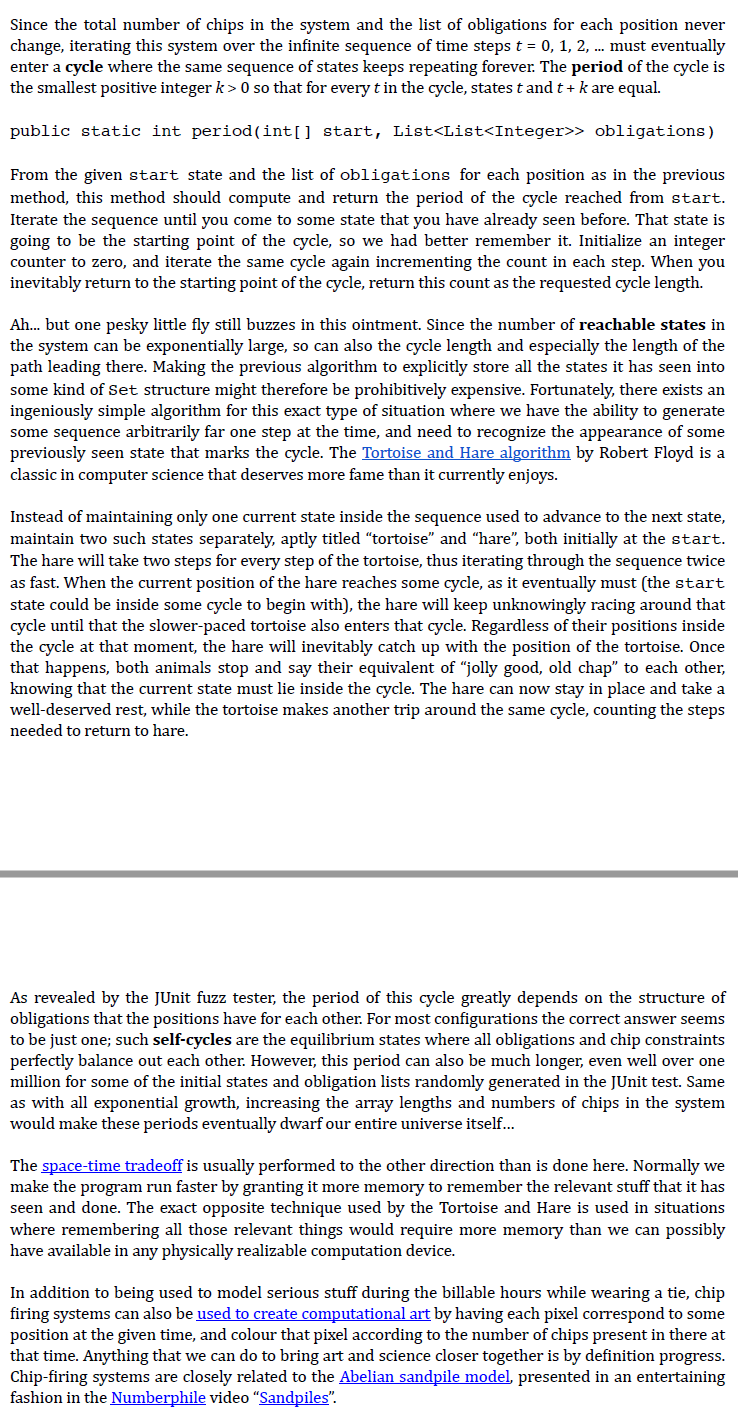

Consider the following operation done for arrays whose elements are nonnegative integers, considered here to be the number of chips. So apologies for the inconsistent terminology used here. The first version of this problem was talking about "coins until the author realized that in the literature of this field, the systems described below are known as chip firing systems. As long as names are sufficiently memorable and unique to keep us from confusing their referents, it's all to- may-to, to-mah-to anyway, at least as far as this author is concerned. Each position in the array also has a list of obligations, each obligation being another position in the array. Each position can have any number of obligations to other positions, and can have multiple obligations to the same position. Time proceeds in discrete steps. For each time step t, the following operation is performed for every position of the array, producing the chip distribution for the next time step t + 1. The logic of your method must be designed so that its result is equivalent to performing this operation in logical unison for every position in an instantaneous atomic step so that all positions fire their chips in unison, as if they were saluting the most powerful maharaja that the brave forces of our Queen had ever had the honour to encounter! Every position that has at least as many chips as the total length of its list of obligations, gives out exactly one chip to each position as many times as it appears in that list. The remaining positions that did not have enough chips to fulfill their obligations do not give out any chips to anybody. This operation does not change the total number of chips inside the system, it just moves them around the positions. The states of this chip-firing system therefore correspond to the possible ways this fixed chip stack can be distributed among the positions. The transitions lead from each state to the next state that results from the previous operation. To allow you to compute these transitions, create a new class CoinMove, and there the method curr int[] next, public static void coinStep(int[] List> obligations) The current state is given in the parameter curr, and the list of obligations for each position is an element of the list of such lists named obligations. (Both lists curr and obligations are guaranteed to have the same length.) This method should not return any result, but instead write the next state into the array next, also guaranteed to be an int[] of sufficient length at the time of the call. The following table showcases some possible values for curr and obligations, and the expected next state that this method is expected to produce: curr obligations Expected next [4, 5] [4, 5] [[1], [0]] [[1, 1], [0, 0]] [3, 1] [1, 3] [2, 3, 0, 1] [3, 1, 0, 2] [[1], [3, 3, 0], [], [0]] [0, 4, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1] [3, 3, 1, 1, 2, 0, 0] [[6, 5, 1], [6, 4, 2, 2], [], [5, 0, 0], [], [], [] [3, 2, 2, 0, 1, 2, 2] [1, 0, 2, 2, 0, 4, 3] [[3, 5], [6, 3], [0, 3, 4], [6, 2], [5], [2, 2, 3, 4, 2, 4, 1, 2, 1], [2] Since the total number of chips in the system and the list of obligations for each position never change, iterating this system over the infinite sequence of time steps t = 0, 1, 2, ... must eventually enter a cycle where the same sequence of states keeps repeating forever. The period of the cycle is the smallest positive integer k> 0 so that for every t in the cycle, statest and t + k are equal. public static int period (int[] start, List

> obligations) From the given start state and the list of obligations for each position as in the previous method, this method should compute and return the period of the cycle reached from start. Iterate the sequence until you come to some state that you have already seen before. That state is going to be the starting point of the cycle, so we had better remember it. Initialize an integer counter to zero, and iterate the same cycle again incrementing the count in each step. When you inevitably return to the starting point of the cycle, return this count as the requested cycle length. Ah... but one pesky little fly still buzzes in this ointment. Since the number of reachable states in the system can be exponentially large, so can also the cycle length and especially the length of the path leading there. Making the previous algorithm to explicitly store all the states it has seen into some kind of Set structure might therefore be prohibitively expensive. Fortunately, there exists an ingeniously simple algorithm for this exact type of situation where we have the ability to generate some sequence arbitrarily far one step at the time, and need to recognize the appearance of some previously seen state that marks the cycle. The Tortoise and Hare algorithm by Robert Floyd is a classic in computer science that deserves more fame than it currently enjoys. Instead of maintaining only one current state inside the sequence used to advance to the next state, maintain two such states separately, aptly titled tortoise" and hare", both initially at the start. The hare will take two steps for every step of the tortoise, thus iterating through the sequence twice as fast. When the current position of the hare reaches some cycle, as it eventually must the start state could be inside some cycle to begin with), the hare will keep unknowingly racing around that cycle until that the slower-paced tortoise also enters that cycle. Regardless of their positions inside the cycle at that moment, the hare will inevitably catch up with the position of the tortoise. Once that happens, both animals stop and say their equivalent of jolly good, old chap to each other, knowing that the current state must lie inside the cycle. The hare can now stay in place and take a well-deserved rest, while the tortoise makes another trip around the same cycle, counting the steps needed to return to hare. As revealed by the JUnit fuzz tester, the period of this cycle greatly depends on the structure of obligations that the positions have for each other. For most configurations the correct answer seems to be just one; such self-cycles are the equilibrium states where all obligations and chip constraints perfectly balance out each other. However, this period can also be much longer, even well over one million for some of the initial states and obligation lists randomly generated in the JUnit test. Same as with all exponential growth, increasing the array lengths and numbers of chips in the system would make these periods eventually dwarf our entire universe itself... The space-time tradeoff is usually performed to the other direction than is done here. Normally we make the program run faster by granting it more memory to remember the relevant stuff that it has seen and done. The exact opposite technique used by the Tortoise and Hare is used in situations where remembering all those relevant things would require more memory than we can possibly have available in any physically realizable computation device. In addition to being used to model serious stuff during the billable hours while wearing a tie, chip firing systems can also be used to create computational art by having each pixel correspond to some position at the given time, and colour that pixel according to the number of chips present in there at that time. Anything that we can do to bring art and science closer together is by definition progress. Chip-firing systems are closely related to the Abelian sandpile model presented in an entertaining fashion in the Numberphile video "Sandpiles". Consider the following operation done for arrays whose elements are nonnegative integers, considered here to be the number of chips. So apologies for the inconsistent terminology used here. The first version of this problem was talking about "coins until the author realized that in the literature of this field, the systems described below are known as chip firing systems. As long as names are sufficiently memorable and unique to keep us from confusing their referents, it's all to- may-to, to-mah-to anyway, at least as far as this author is concerned. Each position in the array also has a list of obligations, each obligation being another position in the array. Each position can have any number of obligations to other positions, and can have multiple obligations to the same position. Time proceeds in discrete steps. For each time step t, the following operation is performed for every position of the array, producing the chip distribution for the next time step t + 1. The logic of your method must be designed so that its result is equivalent to performing this operation in logical unison for every position in an instantaneous atomic step so that all positions fire their chips in unison, as if they were saluting the most powerful maharaja that the brave forces of our Queen had ever had the honour to encounter! Every position that has at least as many chips as the total length of its list of obligations, gives out exactly one chip to each position as many times as it appears in that list. The remaining positions that did not have enough chips to fulfill their obligations do not give out any chips to anybody. This operation does not change the total number of chips inside the system, it just moves them around the positions. The states of this chip-firing system therefore correspond to the possible ways this fixed chip stack can be distributed among the positions. The transitions lead from each state to the next state that results from the previous operation. To allow you to compute these transitions, create a new class CoinMove, and there the method curr int[] next, public static void coinStep(int[] List

> obligations) The current state is given in the parameter curr, and the list of obligations for each position is an element of the list of such lists named obligations. (Both lists curr and obligations are guaranteed to have the same length.) This method should not return any result, but instead write the next state into the array next, also guaranteed to be an int[] of sufficient length at the time of the call. The following table showcases some possible values for curr and obligations, and the expected next state that this method is expected to produce: curr obligations Expected next [4, 5] [4, 5] [[1], [0]] [[1, 1], [0, 0]] [3, 1] [1, 3] [2, 3, 0, 1] [3, 1, 0, 2] [[1], [3, 3, 0], [], [0]] [0, 4, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1] [3, 3, 1, 1, 2, 0, 0] [[6, 5, 1], [6, 4, 2, 2], [], [5, 0, 0], [], [], [] [3, 2, 2, 0, 1, 2, 2] [1, 0, 2, 2, 0, 4, 3] [[3, 5], [6, 3], [0, 3, 4], [6, 2], [5], [2, 2, 3, 4, 2, 4, 1, 2, 1], [2] Since the total number of chips in the system and the list of obligations for each position never change, iterating this system over the infinite sequence of time steps t = 0, 1, 2, ... must eventually enter a cycle where the same sequence of states keeps repeating forever. The period of the cycle is the smallest positive integer k> 0 so that for every t in the cycle, statest and t + k are equal. public static int period (int[] start, List

> obligations) From the given start state and the list of obligations for each position as in the previous method, this method should compute and return the period of the cycle reached from start. Iterate the sequence until you come to some state that you have already seen before. That state is going to be the starting point of the cycle, so we had better remember it. Initialize an integer counter to zero, and iterate the same cycle again incrementing the count in each step. When you inevitably return to the starting point of the cycle, return this count as the requested cycle length. Ah... but one pesky little fly still buzzes in this ointment. Since the number of reachable states in the system can be exponentially large, so can also the cycle length and especially the length of the path leading there. Making the previous algorithm to explicitly store all the states it has seen into some kind of Set structure might therefore be prohibitively expensive. Fortunately, there exists an ingeniously simple algorithm for this exact type of situation where we have the ability to generate some sequence arbitrarily far one step at the time, and need to recognize the appearance of some previously seen state that marks the cycle. The Tortoise and Hare algorithm by Robert Floyd is a classic in computer science that deserves more fame than it currently enjoys. Instead of maintaining only one current state inside the sequence used to advance to the next state, maintain two such states separately, aptly titled tortoise" and hare", both initially at the start. The hare will take two steps for every step of the tortoise, thus iterating through the sequence twice as fast. When the current position of the hare reaches some cycle, as it eventually must the start state could be inside some cycle to begin with), the hare will keep unknowingly racing around that cycle until that the slower-paced tortoise also enters that cycle. Regardless of their positions inside the cycle at that moment, the hare will inevitably catch up with the position of the tortoise. Once that happens, both animals stop and say their equivalent of jolly good, old chap to each other, knowing that the current state must lie inside the cycle. The hare can now stay in place and take a well-deserved rest, while the tortoise makes another trip around the same cycle, counting the steps needed to return to hare. As revealed by the JUnit fuzz tester, the period of this cycle greatly depends on the structure of obligations that the positions have for each other. For most configurations the correct answer seems to be just one; such self-cycles are the equilibrium states where all obligations and chip constraints perfectly balance out each other. However, this period can also be much longer, even well over one million for some of the initial states and obligation lists randomly generated in the JUnit test. Same as with all exponential growth, increasing the array lengths and numbers of chips in the system would make these periods eventually dwarf our entire universe itself... The space-time tradeoff is usually performed to the other direction than is done here. Normally we make the program run faster by granting it more memory to remember the relevant stuff that it has seen and done. The exact opposite technique used by the Tortoise and Hare is used in situations where remembering all those relevant things would require more memory than we can possibly have available in any physically realizable computation device. In addition to being used to model serious stuff during the billable hours while wearing a tie, chip firing systems can also be used to create computational art by having each pixel correspond to some position at the given time, and colour that pixel according to the number of chips present in there at that time. Anything that we can do to bring art and science closer together is by definition progress. Chip-firing systems are closely related to the Abelian sandpile model presented in an entertaining fashion in the Numberphile video "Sandpiles

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts