Question: Pls answer the following guiding questions based on the case study in the picture Liability Management at General Motors 1. How has GM measured its

Pls answer the following guiding questions based on the case study in the pictureLiability Management at General Motors

1. How has GM measured its exposure? How would you propose that GM measures its interest rate exposure? How would you propose that GM reports the interest rate exposure of its business, and of its liabilities?

2. What is a "rate view"? What role does it play in the liability management policy at GM? What role should it play in the liability management program? Why?

3. Explain each of the interest rate derivatives that Bello is considering (listed in Exhibit 7.) How do they work, and how would they affect the incremental interest rate exposure of the five-year fixed-rate note that GM is about to issue? Assuming that each of the instruments is fairly priced, what should Bello recommend? Why?

4. As a director or institutional investor in GM, how would you evaluate the liability management program at GM? What might you suggest should be studied or changed, and why?

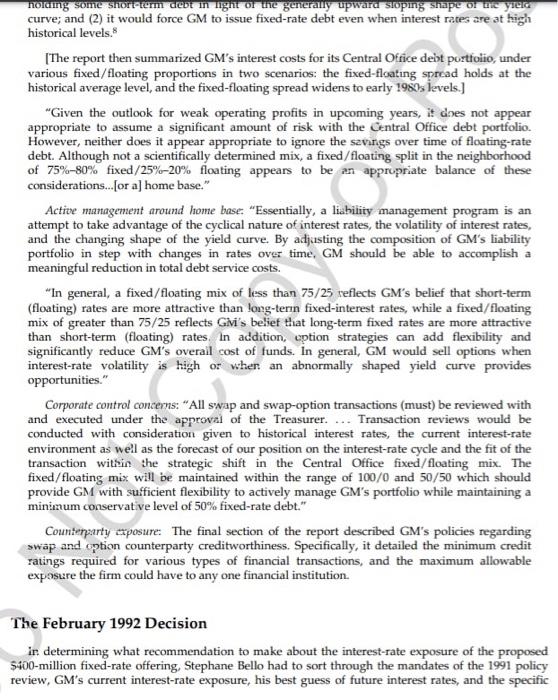

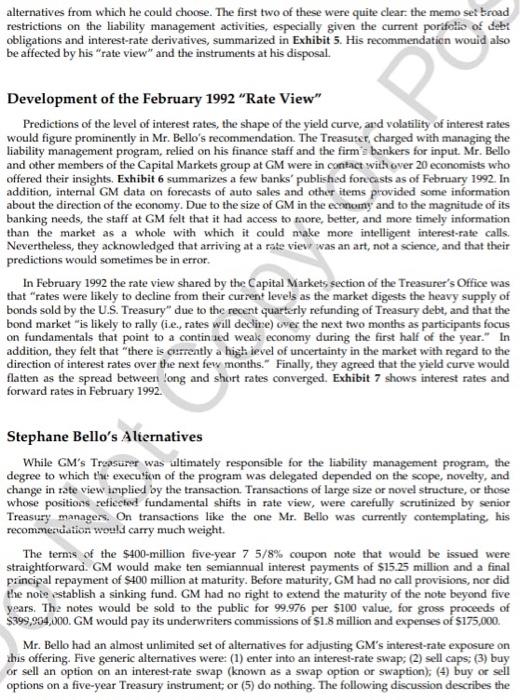

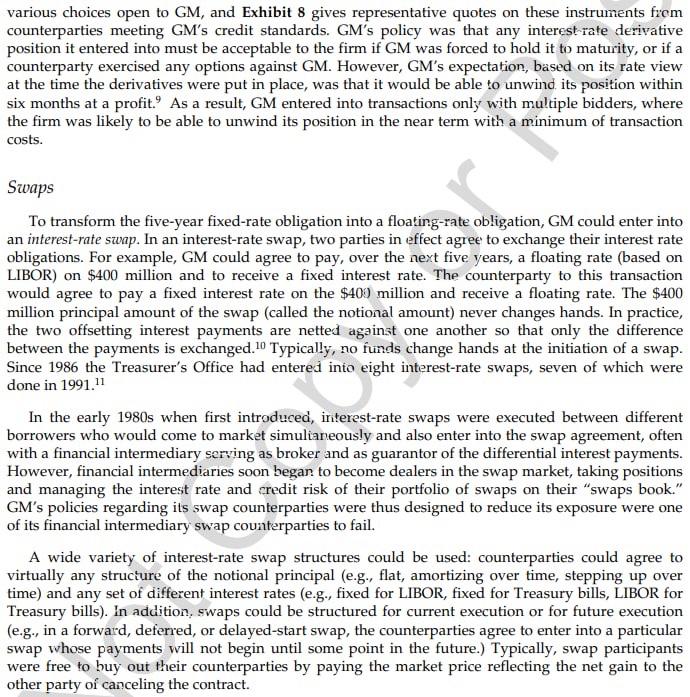

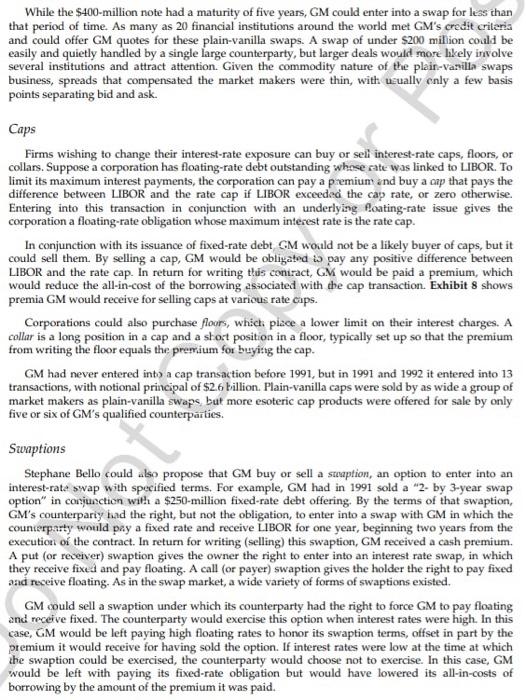

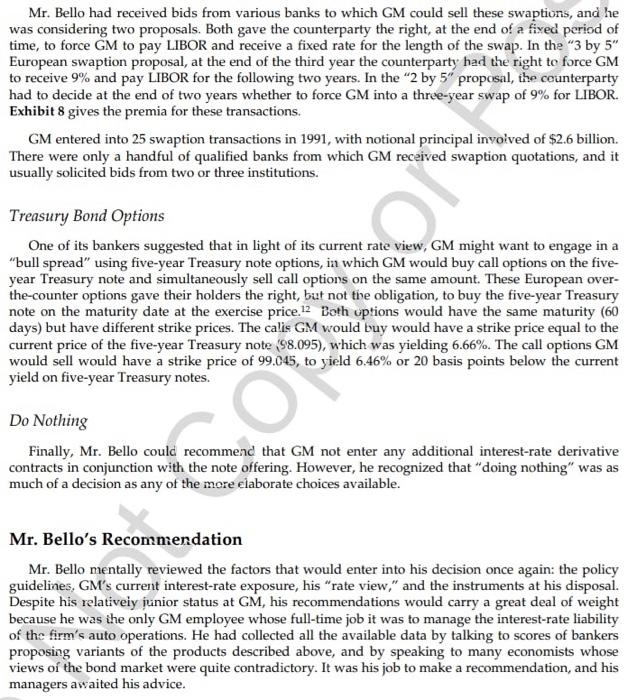

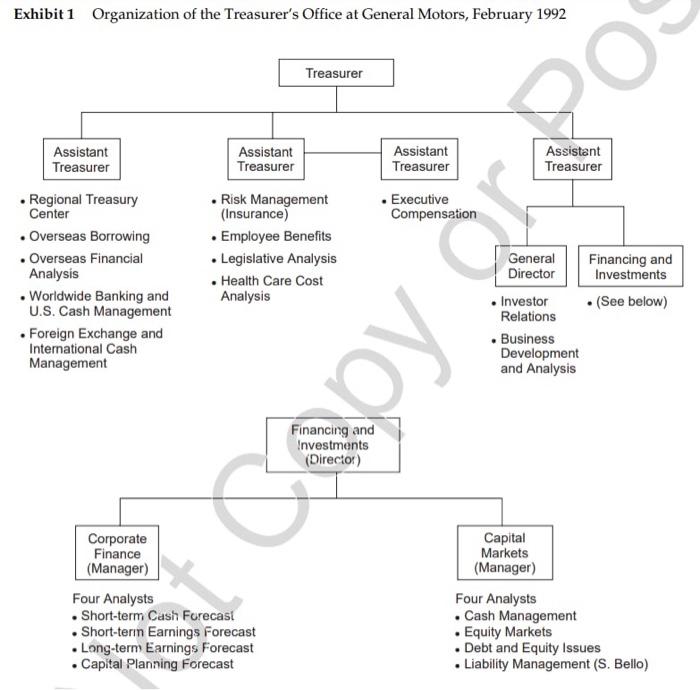

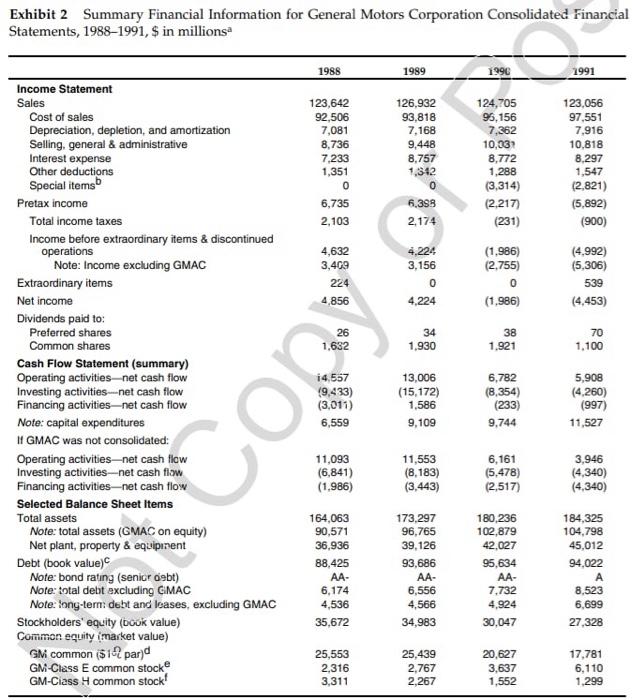

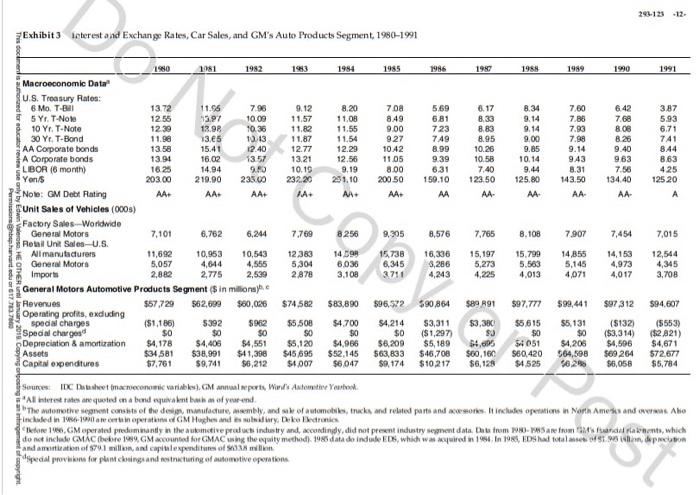

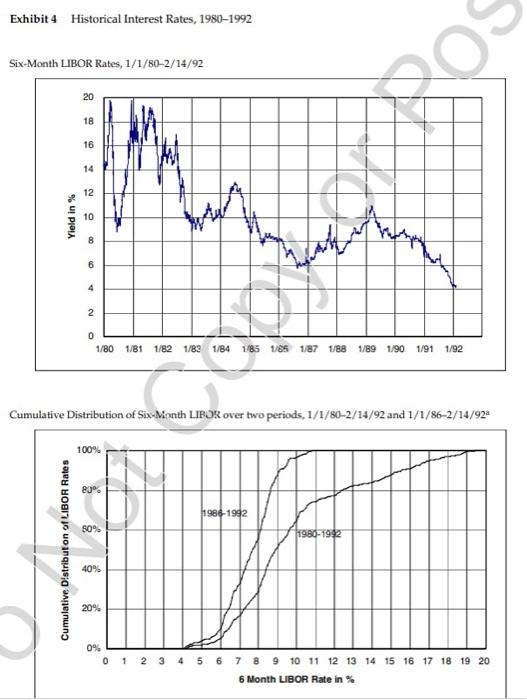

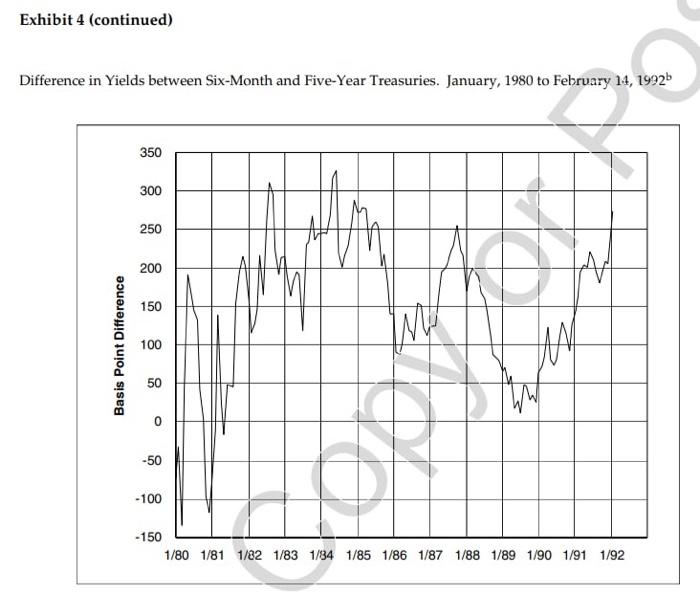

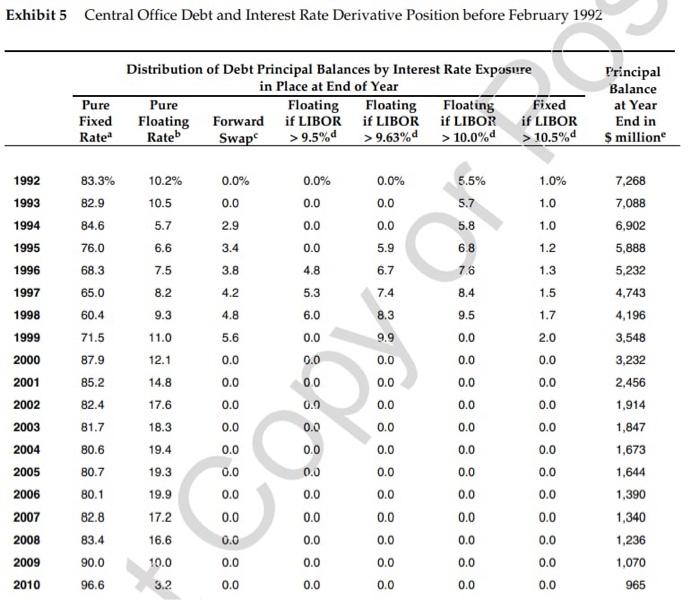

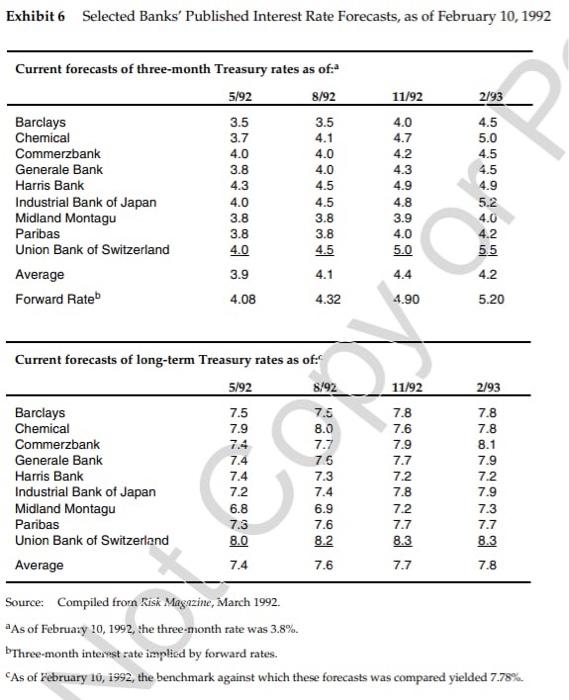

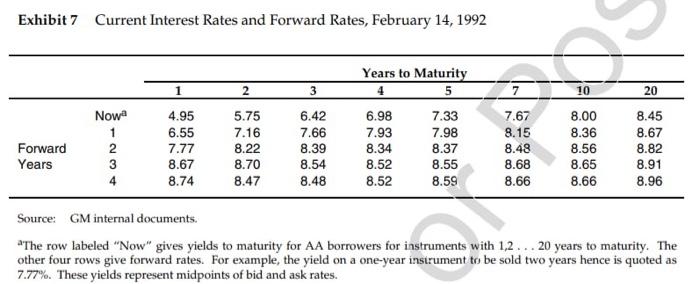

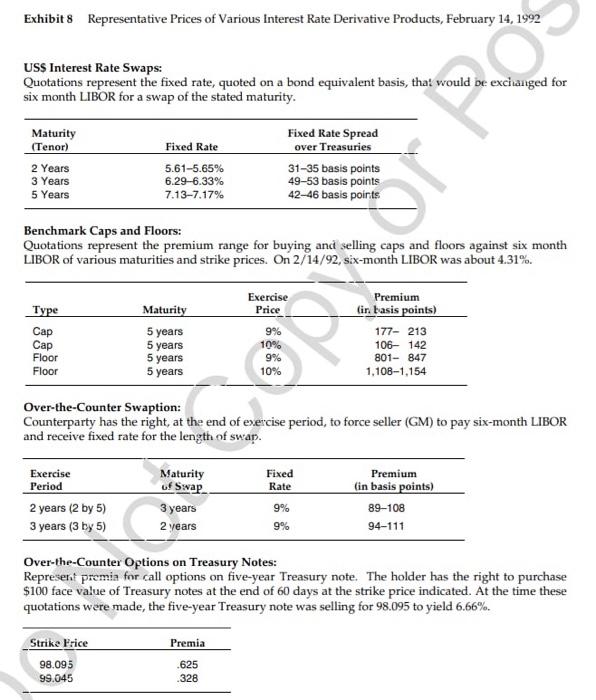

Liability Management at General Motors Stephane Bello, an analyst in the Capital Markets group at General Motors (GM), oversaw liability portfolio analysis activities for America's largest domestic automaker. In February 1992, GM was planning to raise $400 million through a public offering of a noncallable five-year note, with a fixed interest rate of 7 5/8%. Guided by the firm's stated policy on liability portfolio management, the current structure of its liabilities, and his best reading of likely trends in the bond markets, Mr. Bello had to recommend to senior GM Treasurer's Office managers whether to modify GM's interest rate exposure on the issue and, if so, which transaction to select. Mr. Bello had been in the Capital Markets group at GM for one year, and during that time was responsible for analyzing the management of GM's interest-rate exposure and making recommendations about how GM could lower its borrowing costs through prudent use of interest- rate derivative products. Before taking this position, Mr. Bello had worked for two years in GM's European Regional Treasury Center, engaged in foreign exchange and corporate financing transactions. Before joining GM, he had worked in a commercial bank for over a year. Mr. Bello could advise that the firm merely issue fixed-rate debt and not engage in any related transactions. He could also suggest that GM engage in a wide range of derivative activities, which included transacting in interest-rate swaps, caps, Treasury options, or swap options (swaptions). He had solicited competitive bids for each of these instruments from several bankers. His recommendation would hinge on his judgment of the future level of interest rates and volatility, the future shape of the yield curve, and the interest-risk exposure each instrument would create in light of the overall interest-rate management program at GM. Background on General Motors and the Auto Industry In 1991, General Motors was the world's largest automaker and the nation's largest industrial company. It was broadly organized into four major operating segments: Automotive; General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC), which provided a variety of financial services; GM Hughes Flectronics, acquired in 1985, which competed in the aerospace, defense electronics, space, and telecommunications industries; and Electronic Data Services (EDS), acquired in 1984, which provided data-processing services to large corporations and institutions. GM's Automotive segment designed, manufactured, assembled, and sold automobiles, trucks, parts, and accessories. Its automotive nameplates included Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick, Cadillac, GMC Truck, and Satun in the United States, as well as Holdens, OPEL, and Vauxhall in overseas countries. While GM's nonauto businesses produced profits in 1991, its auto business sitfiered a second consecutive year of large operating losses. In 1990 the automotive segment reported an operating loss of $3.4 billion, of which $3.3 billion was a special provision for scheduled plant closings and other restructurings. In 1991 the automotive segment reported an even greater loss, $6.2 billion, of which $2.8 billion was a special provision for scheduled plant closings. In 1991 GM cut tis annual common stock dividend from $3.00 to $1.60, roughly the level it had been in 1983. In December 1991, GM's chairman and CEO, Robert C. Stempel, announced the newest cutbacks, which were scheduled to close 21 factories, cut 74,000 jobs, and slash capital spending over four years. While analysts generally supported the firm's restructuring efforts, which would ultimately cut costs by $5 billion annually, North American auto operations were not expected to become profitable for at least a few years. Exhibit 2 gives selected financial information on General Motors at a consolidated level, and Exhibit 3 gives the performance of the firm's automotive segment over the past decade. Exhibit 3 also provides information on interest rates and exchange rates during the same period of time. Financial Policies at GM At least two aspects of GM's financial strategy were reviewed in great detail in 1991. In the first of these efforts, Ray Young (who oversaw corporate finance activities in the Treasurer's Office) and his staff carefully analyzed the corporation's current capital structure policy. (See Exhibit 1 for an organization chart of the Treasurer's Office at General Motors at the time of the case.) Ultimately their conclusions regarding the GM balance sheet were reviewed by GM's Treasurer, CFO, and other senior executives. Financial targets examined, which were not announced publicly, included book value debt-to-total capital ratios, interest coverage ratios, and cash flow coverage ratios. The target ranges were set mindful of the rating agencies' guidelines, competitor's debt policies, and Young's estimates of the firm's cost of funds and its likely access to capital under various scenarios. Of utmost concern was the shared belief that declines in the company's debt ratings could make raising funds very difficult and thus lead to unintended shrinkage in the firm's auto activities. The capital structure recommendation provided policy direction and guidance to the Capital Markets group charged with executing specific transactions. Nevertheless, the Capital Markets group had wide latitudefor example, issuing "debt" implied a set of decisions about which market the instrument would tap (domnestic U.S. Euromarkets, or other), the maturity of the instrument, its interest rate (fixed or floating), and other specific terms like callable features, sinking funds, etc.? In addition, the capital markets in the 1980s and early 1990s had developed an almost unbounded number of derivative instruments that could dramatically alter the fundamental economics of an offering. For example, a firm could issue a fixed-rate note, and then engage in a swap transaction with a financal institution to pay a floating rate tied to LIBOR and receive a fixed rate. The issuer then effectively transformed the fixed-rate issue into a LIBOR-linked floating-rate note. GM did not engage in derivative transactions to modify the interest-rate exposure of its debt offerings until 1989, when the manager of the Capital Markets group suggested that the firm experiment with swaps and other interest-rate derivatives to lower GM's borrowing costs. This effort proceeded after receiving ultimate approval from the Finance Committee of the Board of Directors. However, throughout 1989 and 1990, GM's borrowing needs were modest, and thus it engaged in very few interest-rate derivative transactions. The early transactions were structured as relatively low-risk experiments designed to reduce GM's cost of debt. Because the group lacked internal capabilities to price interest-rate derivatives, it was decided that GM would engage in transactions only when they could obtain independent prices from competing financial institutions. Requiring multiple vendors to submit bids may have ruled out some of the most esoteric transactions in the market, but it also gave GM some assurance that it would not be at the mercy of one bank if it wanted to unwind its positions before maturity. Beginning with its 1990 annual report, GM notified the public of its use of interest rate derivatives to manage its exposure as part of its SFAS 105 disclosure: The Corporation primarily utilizes interest-rate-forward contracts or options to manage its interest-rate exposure. Interest-rate-forward contracts are contractual agreements between the Corporation and another party to exchange fixed and floating interest-rate payments periodically over the life of the agreement without the exchange of underlying principal amounts. Interest-rate options generally permit but do not require the purchaser of the option to exchange interest-rate payments in the future. At December 31, 1990, the total notional amount of such agreements with off- balance sheet risk was approximately $7,787 million.' By the end of 1991, this notional principal equaied $7,354 million. The amounts disclosed in GM's annual reports included interest-rate derivatives transactions executed by GMAC. However, the New York Treasurer's Office was not directly involved with GMAC's liability management program, which was handled out of GMAC's Treasury operations in Detroit. The required disclosure contained in the GM financial statements did not reveal the number, complexity, or economic exposure brought about by the firm's recent interest-rate management activities. For example, in its first two years of managing interest-rate risk actively, GM had entered into seven different transactions, including a single interest swap and a handful of more complicated swap options or swaptions. In 1991, GM's liability management program became more formalized and increased in scope, for in that year the firm entered into 40 interest-rate derivative transactions. This increase in scale was facilitated by the hiring of a full-time analyst charged with analyzing and recommending potential structures to manage CM's growing liability portfolio. The heightened activity also led to a formal review of GM's liability management policies. This review sought to evaluate the firm's first two years of experience in managing the structure of its debl, as well as lo lay oul guidelines for 'uiure liability management activities. This policy review set broad boundaries within which interest rate management of Central Office debt obligations would take place. The 1991 Review of GM's Liability Management Program The 1991 review established a rationale and a set of policies for managing the debt of GM's auto operations, just as the review of capital structure provided a long-term view of the firm's mix of debt and equity. The report covered the goal of the program, the economic rationale for a "home base" mix of fixed/floating obligations, the role of changing market conditions on the active management of the portfolio, corporate governance concerns, and criteria for counterparty credit exposure. The following excerpts summarize key findings: Goal: "To actively manage the Central Office liabilities to take advantage of the cyclical nature and volatility of domestic interest rates and shiits in the shape of the yield curve to reduce GM's overall cost of funds. Home base: "Asset/Liability management can be broadly defined as matching the nature of a company's liabilities to its assets to limit the impact of interest-rate movements on the company's net cash flows and hence corporate value. In general, this is accomplished by adjusting a firm's financial liability portfolio such that any impact on operating cash flow caused by movements in interest rates is largely offset by changes in the value of the firm's liability portfolio "(In) industrial companies ... the impact of changes in interest rates on operating cash flows is hard to quantify. ... In addition, the right-hand side of an industrial company's balance sheet tends to comprise a higher percentage of equity and noninterest-bearing liabilities (i.e., accounts payable, reserves for warranties, incentives, and deferred taxes) than a financial institution's. This means that, even if the correlation between changes in interest rates and changes in operating cash flows could be perfectly established, the value of financial liabilities would probabiy have to be hedged to an extreme to obtain the desired results. "GM's North American automotive revenues and hence operating cash flows are strongly influenced by rovements in interest-rates ... a 1% decrease in auto loan rates results in a 0.2% increase in the dollar volume of cars sold.? ... GM's automotive operations behave more like fixed-rate assets than floating-rate assets... Therefore, GM's Central Office liability portfolio should be predominantly fixed-rate in nature to provide the greatest insulation to GM's cash flows from a rising interest-rate/slow automotive market. "Although a fixed / floating rate mix of 100/0 would completely insulate GM's debt service cash flows from rising interest rates... (1) it would ignore the cost benefits to be derived by holding some short-term cent in light of the generally upward sloping shape of we yer curve; and (2) it would force GM to issue fixed-rate debt even when interest rates are at high historical levels. [The report then summarized GM's interest costs for its Central Office debt portfolio, under various fixed/floating proportions in two scenarios: the fixed-floating spread holds at the historical average level, and the fixed-floating spread widens to early 1980s levels.] "Given the outlook for weak operating profits in upcoming years, it does not appear appropriate to assume a significant amount of risk with the Central Office debt portfolio. However, neither does it appear appropriate to ignore the savings over time of floating-rate debt. Although not a scientifically determined mix, a fixed/floating split in the neighborhood of 75%-80% fixed/25%-20% floating appears to be an appropriate balance of these considerations...[or a home base." Active management around home base: "Essentially, a liability management program is an attempt to take advantage of the cyclical nature of interest rates, the volatility of interest rates, and the changing shape of the yield curve. By adjusting the composition of GM's liability portfolio in step with changes in rates over time, GM should be able to accomplish a meaningful reduction in total debt service costs. "In general, a fixed/floating mix of less than 75/25 reflects GM's belief that short-term (floating) rates are more attractive than long-terin fixed-interest rates, while a fixed/floating mix of greater than 75/25 reflects GM's belief that long-term fixed rates are more attractive than short-term (floating) rates. In addition, eption strategies can add flexibility and significantly reduce GM's overall cost of funds. In general, GM would sell options when interest-rate volatility is high or wher: an abnormally shaped yield curve provides opportunities." Corporate control concerns: "All swap and swap-option transactions (must) be reviewed with and executed under the approval of the Treasurer. ... Transaction reviews would be conducted with consideration given to historical interest rates, the current interest-rate environment as well as the forecast of our position on the interest-rate cycle and the fit of the transaction within the strategic shift in the Central Office fixed/floating mix. The fixed/floating mix will be maintained within the range of 100/0 and 50/50 which should provide GM with sufficient flexibility to actively manage GM's portfolio while maintaining a minimum conservative level of 50% fixed-rate debt." Countenarty exposure: The final section of the report described GM's policies regarding swap and option counterparty creditworthiness. Specifically, it detailed the minimum credit ratings required for various types of financial transactions, and the maximum allowable exposure the firm could have to any one financial institution. The February 1992 Decision ir determining what recommendation to make about the interest-rate exposure of the proposed $100-million fixed-rate offering, Stephane Bello had to sort through the mandates of the 1991 policy review, GM's current interest-rate exposure, his best guess of future interest rates, and the specific alternatives from which he could choose. The first two of these were quite clear the memo set broad restrictions on the liability management activities, especially given the current porifolio of debt obligations and interest-rate derivatives, summarized in Exhibit 5. His recommendation wouid also be affected by his "rate view" and the instruments at his disposal Development of the February 1992 "Rate View" Predictions of the level of interest rates, the shape of the yield curve, and volatility of interest rates would figure prominently in Mr. Bello's recommendation. The Treasurer, charged with managing the liability management program, relied on his finance staff and the firm's bankers for input. Mr. Bello and other members of the Capital Markets group at GM were in contact with over 20 economists who offered their insights. Exhibit 6 summarizes a few banks' published forecasts as of February 1992. In addition, internal GM data on forecasts of auto sales and other items provided some information about the direction of the economy. Due to the size of GM in the economy and to the magnitude of its banking needs, the staff at GM felt that it had access to more, better, and more timely information than the market as a whole with which it could make more intelligent interest-rate calls. Nevertheless, they acknowledged that arriving at a rate view was an art, not a science, and that their predictions would sometimes be in error. In February 1992 the rate view shared by the Capital Markets section of the Treasurer's Office was that "rates were likely to decline from their current levels as the market digests the heavy supply of bonds sold by the U.S. Treasury" due to the recent quarterly refunding of Treasury debt, and that the bond market "is likely to rally (i.e., rates will decine) over the next two months as participants focus on fundamentals that point to a continued weak economy during the first half of the year." In addition, they felt that there is currently a high level of uncertainty in the market with regard to the direction of interest rates over the next few months." Finally, they agreed that the yield curve would flatten as the spread between long and short rates converged. Exhibit 7 shows interest rates and forward rates in February 1992. Stephane Bello's Alternatives While GM's Treasurer was altimately responsible for the liability management program, the degree to which the execution of the program was delegated depended on the scope, novelty, and change in rate view implied by the transaction. Transactions of large size or novel structure, or those whose positions refiected fundamental shifts in rate view, were carefully scrutinized by senior Treasury managers. On transactions like the one Mr. Bello was currently contemplating, his recommendation would carry much weight The terns of the $400-million five-year 7 5/8% coupon note that would be issued were straightforward. GM would make ten semiannual interest payments of $15.25 million and a final principal repayment of S400 million at maturity. Before maturity, GM had no call provisions, nor did the nose establish a sinking fund. GM had no right to extend the maturity of the note beyond five years. The notes would be sold to the public for 99.976 per $100 value for gross proceeds of $399,904,000. GM would pay its underwriters commissions of S1.8 million and expenses of $175,000 Mr. Bello had an almost unlimited set of alternatives for adjusting GM's interest-rate exposure on this offering. Five generic alternatives were: (1) enter into an interest-rate swap; (2) sell caps; (3) buy or sell an option on an interest-rate swap (known as a swap option or swaption); (4) buy or sell options on a five-year Treasury instrument, or (5) do nothing. The following discussion describes the various choices open to GM, and Exhibit 8 gives representative quotes on these instruments frem counterparties meeting GM's credit standards. GM's policy was that any interest rate derivative position it entered into must be acceptable to the firm if GM was forced to hold it to maturity, or if a counterparty exercised any options against GM. However, GM's expectation, based on its rate view at the time the derivatives were put in place, was that it would be able to unwind its position within six months at a profit. As a result, GM entered into transactions only with multiple bidders, where the firm was likely to be able to unwind its position in the near term with a minimum of transaction costs. Swaps To transform the five-year fixed-rate obligation into a floating-rate obligation, GM could enter into an interest-rate swap. In an interest-rate swap, two parties in effect agree to exchange their interest rate obligations. For example, GM could agree to pay, over the next five years, a floating rate (based on LIBOR) on $400 million and to receive a fixed interest rate. The counterparty to this transaction would agree to pay a fixed interest rate on the $400 million and receive a floating rate. The $400 million principal amount of the swap (called the notional amount) never changes hands. In practice, the two offsetting interest payments are netted against one another so that only the difference between the payments is exchanged. 10 Typically, no funds change hands at the initiation of a swap. Since 1986 the Treasurer's Office had entered into eight interest-rate swaps, seven of which were done in 1991.11 In the early 1980s when first introduced, interest-rate swaps were executed between different borrowers who would come to market simultaneously and also enter into the swap agreement, often with a financial intermediary serving as broker and as guarantor of the differential interest payments. However, financial intermediaries soon began to become dealers in the swap market, taking positions and managing the interest rate and credit risk of their portfolio of swaps on their "swaps book." GM's policies regarding its swap counterparties were thus designed to reduce its exposure were one of its financial intermediary swap counterparties to fail. A wide variety of interest-rate swap structures could be used: counterparties could agree to virtually any structure of the notional principal (e.g., flat, amortizing over time, stepping up over time) and any set of different interest rates (e.g., fixed for LIBOR, fixed for Treasury bills, LIBOR for Treasury bills). In addition, swaps could be structured for current execution or for future execution (e.g., in a forward, deferred, or delayed-start swap, the counterparties agree to enter into a particular swap whose payments will not begin until some point in the future.) Typically, swap participants were free to buy out their counterparties by paying the market price reflecting the net gain to the other party of canceling the contract. Mr. Bello had received bids from various banks to which GM could sell these swaptions, and he was considering two proposals. Both gave the counterparty the right at the end of a fixed period of time, to force GM to pay LIBOR and receive a fixed rate for the length of the swap. In the "3 by 5" European swaption proposal, at the end of the third year the counterparty had the right to force GM to receive 9% and pay LIBOR for the following two years. In the "2 by 5" proposal, the counterparty had to decide at the end of two years whether to force GM into a three-year swap of 9% for LIBOR. Exhibit 8 gives the premia for these transactions. GM entered into 25 swaption transactions in 1991, with notional principal involved of $2.6 billion. There were only a handful of qualified banks from which GM received swaption quotations, and it usually solicited bids from two or three institutions. . Treasury Bond Options One of its bankers suggested that in light of its current rate view, GM might want to engage in a "bull spread" using five-year Treasury note options, in which GM would buy call options on the five- year Treasury note and simultaneously sell call options on the same amount. These European over- the-counter options gave their holders the right, but not the obligation, to buy the five-year Treasury note on the maturity date at the exercise price. 12 Both options would have the same maturity (60 days) but have different strike prices. The calis GM would buy would have a strike price equal to the current price of the five-year Treasury note (98.095), which was yielding 6.66%. The call options GM would sell would have a strike price of 99.045, to yield 6.46% or 20 basis points below the current yield on five-year Treasury notes. Do Nothing Finally, Mr. Bello could recommend that GM not enter any additional interest-rate derivative contracts in conjunction with the note offering. However, he recognized that "doing nothing" was as much of a decision as any of the more elaborate choices available. co Mr. Bello's Recommendation Mr. Bello mentally reviewed the factors that would enter into his decision once again: the policy guidelines, GM's current interest-rate exposure, his "rate view," and the instruments at his disposal. Despite his relatively junior status at GM, his recommendations would carry a great deal of weight because he was ihe only GM employee whose full-time job it was to manage the interest-rate liability of the firm's auto operations. He had collected all the available data by talking to scores of bankers proposing variants of the products described above, and by speaking to many economists whose views of the bond market were quite contradictory. It was his job to make a recommendation, and his managers awaited his advice. Exhibiti Organization of the Treasurer's Office at General Motors, February 1992 O Treasurer DO Assistant Treasurer Assistant Treasurer Assistant Treasurer . Executive Compensation Assistant Treasurer . Regional Treasury Center . Overseas Borrowing . Overseas Financial Analysis . Worldwide Banking and U.S. Cash Management . Foreign Exchange and International Cash Management . Risk Management (Insurance) . Employee Benefits . Legislative Analysis . Health Care Cost Analysis Financing and Investments . (See below) General Director Investor Relations . Business Development and Analysis Financing and Investments (Director) C Corporate Finance (Manager) Four Analysts Short-term Cash Forecast . Short-terin Earnings Forecast . Long-term Earnings Forecast . Capital Planning Forecast Capital Markets (Manager) Four Analysts . Cash Management . Equity Markets Debt and Equity Issues . Liability Management (S. Bello) . Exhibit 2 Summary Financial Information for General Motors Corporation Consolidated Financial Statements, 19881991, $ in millions 1988 1989 1990 1991 123,642 92,506 7,081 8,736 7,233 1,351 0 6,735 2,103 126,932 93,818 7,168 9,448 8,757 1,342 0 6.388 2.174 124,705 95, 156 7,362 10,03 8,772 1,288 (3,314) (2.217) (231) 123,056 97,551 7,916 10,818 8,297 1.547 (2,821) (5,892) (900) 4,632 3,469 224 4,856 4.224 3,156 0 4,224 (4.992) (5,306) 539 (4,453) 34 1,930 70 1.100 Income Statement Sales Cost of sales Depreciation, depletion, and amortization Selling, general & administrative Interest expense Other deductions Special items Pretax income Total income taxes Income before extraordinary items & discontinued operations Note: Income excluding GMAC Extraordinary items Net income Dividends paid to: Preferred shares Common shares Cash Flow Statement (summary) Operating activities-net cash flow Investing activities--net cash flow Financing activities-net cash flow Note: capital expenditures IGMAC was not consolidated: Operating activities-net cash flow Investing activities--net cash flow Financing activities-net cash flow Selected Balance Sheet Items Total assets Note: total assets (GMAC on equity) Net plant, property & equipment Debt (book value) Note: bond rating (senior debt) Note: total debt excluding GMAC Note: long-term: debt and leases, excluding GMAC Stockholders' equity (bouk value) Common equity imarket value) GM common (512 pard GM-Class E common stock GM-Class H common stock dog 13,006 (15,172) 1,586 9,109 6,782 (8,354) (233) 9.744 5,908 (4,260) (997) 11,527 11,093 (6,841) (1.986) 11,553 (8,183) (3,443) 6,161 (5,478) (2,517) 3,946 (4.340) (4.340) 164,063 90,571 36,936 88,425 A4- 6,174 4,536 35,672 173,297 96,765 39,126 93,686 . 6,556 4,566 34,983 180,236 102,879 42,027 95,634 AA- 7.732 4,924 30,047 184,325 104,798 45,012 94,022 A 8.523 6,699 27,328 25,553 2,316 3,311 25,439 2,767 2,267 20,627 3,637 17,781 6,110 1.299 1,552 293.125-12 Exhibit3 Interest and Exchange Rates, Car Sales, and GM's Auto Products Segment, 1980-1991 1984 1985 1986 1980 1989 1990 1991 7.80 ford 7.88 9.12 11.57 11.82 11.87 12.77 13.21 10.19 6.17 8.33 8.83 8.95 8.34 9.14 9.14 9.00 7.93 8.20 11.08 11.55 11.54 12.29 12.56 9.19 251.10 An 700 8.49 9.00 927 10.42 11 05 8.00 200 50 AA. 5.69 6.81 723 749 8.99 9.39 6.31 150.10 AA 10.26 9.85 6.42 7.68 8.08 8.26 9.40 963 7.56 134.40 AA 3.87 5.93 6.71 741 8.44 8.63 425 125.20 7.98 9.14 943 8.31 143.50 AA 10.58 7.40 123.50 AA 232.26 10.14 9.44 125.80 AA A. A 1980 1981 1982 Macroeconomic Data U.S. Treasury Rates: 6 Mo T-B1 13.72 11.55 7.96 5 Yr. T-Nole 1256 13.97 10.09 10 Yr.T-Note 1238 13.98 10.36 30 YC.T-Bond 11.90 13.05 13.13 AA Corporate bonds 13.58 15.41 12.40 A Corporate bonds 13.94 16.02 13.57 LIBOR (6 month) 16.25 14.94 9.15 Yon/ 203.00 219.90 235.00 Note: GM Debt Rating AA. AA. AA+ Unit Sales of Vehicles (000) Factory Sales-Worldwide General Motors 7,101 6,762 6,244 Retail Unt Sales - U.S. All manufacturers 11,692 10,953 10,543 General Motors 5,057 4,644 4,555 Imports 2.882 2,775 2,539 General Motors Automotive Products Segment ($ in millione Revenues $57.729 $62,699 $60,026 Operating profits, exduding spedal charges ($1,186) 5392 5982 Special charges $0 $0 SO Depreciation & amortization $4,178 $4,408 $4,551 Assets $34.581 $38,991 $41,398 Capitoxpenditures 57.761 $9,741 $6,212 7.769 8 256 9.305 8,576 Permission harvard.edur 1773760 review use only by Edwin Valerose. HE OTHER January 7.765 8.108 7.907 7,454 7,015 12383 5.304 2878 14599 6.036 3,108 15.738 6,345 3711 16,336 3,286 4,243 15,197 5,273 4.225 15.799 5.563 4.013 14,855 5,145 4,071 14,153 4,973 4,017 12,544 4,345 3,708 $74582 $83,890 $90.864 $89 R91 $97.777 $99,441 $97 312 $94.607 $5.508 SO $5,120 $45,695 $4007 $4.700 $0 $4,986 $52,145 $6.047 $96,572 $4,214 $0 $8,209 563,833 $9, 174 $3,311 ($1.297 $5,189 $46,700 $10,217 $3.380 SJ $4,005 $60,160 $6,128 $5,615 SO 54051 560.420 $4.525 $5.131 $0 $4,206 564,598 56.28 ($132 ($3,314) $4,596 569 264 $6,058 (5553) ($2 821) $4,671 572,677 $5,784 Sources: IDC De maceconomic variables). Malers, Wan Atomise Your All interest rates are used on a bondatbah of yourend the somethve negent cansate of the deutschure membly, and sale of automobile, tracks and related parts and accesories. It includes apetitions in North Amesha and are Alto included in 1919 recin perfGM Hughes and solary Duke Bedronic Before 19, GM operated predominantly in the automotive prach industry and accordingly, did not present industry segment data Dates from 1905 retro's and Manants, which do not include GMACthere 1999. GM accounted for GMAC ning the equity methods. 1985 data de indude EDS, which was quired in 1994 In 1981, EDSH total of 1., depiction and maintain of 74.1 million, and capitalexpenditures of special provide for plantering and restructuring of automotive operations gyon Exhibit 4 Historical Interest Rates, 19801992 Ps Six-Month LIBOR Rates, 1/1/80-2/14/92 20 18 16 14 12 Yield in % 10 B 6 Maak 4 2 0 0 1/80 1/B1 1/82 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 1/92 Cumulative Distribution of Six-Month LIBOR over two periods, 1/1/80-2/14/92 and 1/1/86-2/14/92a 100% 83 1986-1992 50% 1980-1992 Cumulative Distributon of LIBOR Rates 40% 20% 0% 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 6 Month LIBOR Rate in % Exhibit 4 (continued) Difference in Yields between Six-Month and Five-Year Treasuries. January, 1980 to February 14, 1992b 350 300 250 200 150 Basis Point Difference w 100 AM 50 0 -50 -100 - 150 1/80 1781 1/82 1/83 1784 1785 1786 1787 1788 1789 1/90 1/91 1/92 Exhibit 5 Central Office Debt and Interest Rate Derivative Position before February 1992 Pure Fixed Rate" Distribution of Debt Principal Balances by Interest Rate Exposure in Place at End of Year Pure Floating Floating Floating Fixed Floating Forward if LIBOR if LIBOR if LIBOR if LIBOR Rateb Swap > 9.5% > 9.63% > 10.0% > 10.5% Principal Balance at Year End in $ million 1992 5.5% 1.0% 83.3% 82.9 10.2% 10.5 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 1993 1.0 1994 84.6 5.7 2.9 0.0 1.0 76.0 6.6 3.4 0.0 1.2 7.5 3.8 1.3 8.2 4.2 1.5 9.3 4.8 1.7 11.0 5.6 0.0 2.0 12.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 14.8 0.0 17.6 7,268 7,088 6,902 5,888 5,232 4,743 4.196 3,548 3,232 2,456 1,914 1,847 1,673 1,644 1.390 1,340 1,236 1,070 965 0.0 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 0.0 68.3 65.0 60.4 71.5 87.9 85.2 82.4 81.7 80.6 80.7 80.1 82.8 83.4 90.0 18.3 0.0 0.0 19.4 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 19.3 19.9 17.2 16.6 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 96.6 3.2 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Exhibit 6 Selected Banks' Published Interest Rate Forecasts, as of February 10, 1992 11/92 2/93 Current forecasts of three-month Treasury rates as of: 5/92 8/92 Barclays 3.5 3.5 Chemical 3.7 4.1 Commerzbank 4.0 4.0 Generale Bank 3.8 4.0 Harris Bank 4.3 4.5 Industrial Bank of Japan 4.0 4.5 Midland Montagu 3.8 3.8 Paribas 3.8 3.8 Union Bank of Switzerland 4.0 4.5 Average 3.9 4.1 Forward Rate 4.08 4.32 4.0 4.7 4.2 4.3 4.9 4.8 3.9 4.0 5.0 +10 NOUT Unoon 55 4.4 4.2 4.90 5.20 Current forecasts of long-term Treasury rates as of: 5/92 8/92 2/93 NNNN Barclays Chemical Commerzbank Generale Bank Harris Bank Industrial Bank of Japan Midland Montagu Paribas Union Bank of Switzerland Average AWODOO 11/92 7.8 7.6 7.9 7.7 7.2 7.8 7.2 7.7 8.3 NON O O O 78777767 7.8 7.8 8.1 7.9 7.2 7.9 7.3 7.7 8.0 8.3 8.2 7.6 7.4 7.7 7.8 Source: Compiled from Kisk Magazine, March 1992. As of February 10, 1992, the three-month rate was 3.8%. bThree-month interest rate implied by forward rates. CAs of February 10, 1992, the benchmark against which these forecasts was compared yielded 7.78% Exhibit 7 Current Interest Rates and Forward Rates, February 14, 1992 1 2 3 7 10 20 Now 1 2 3 4 Forward Years 4.95 6.55 7.77 8.67 5.75 7.16 8.22 8.70 8.47 Years to Maturity 4 5 6.98 7.33 7.93 7.98 8.34 8.37 8.52 8.52 6.42 7.66 8.39 8.54 8.48 7.67 8.15 8.48 8.68 8.66 8.00 8.36 8.56 8.65 8.66 8.45 8.67 8.82 8.91 8.96 8.74 Source: GM internal documents. The row labeled "Now" gives yields to maturity for AA borrowers for instruments with 1,2 ... 20 years to maturity. The other four rows give forward rates. For example, the yield on a one-year instrument to be sold two years hence is quoted as 7.77%. These yields represent midpoints of bid and ask rates. Exhibit8 Representative Prices of Various interest Rate Derivative Products, February 14, 1992 US$ Interest Rate Swaps: Quotations represent the fixed rate, quoted on a bond equivalent basis, that would be exchanged for six month LIBOR for a swap of the stated maturity. Maturity (Tenor) 2 Years 3 Years 5 Years Fixed Rate 5.61-5.65% 6.29-6.33% 7.13-7.17% Fixed Rate Spread over Treasuries 31-35 basis points 49-53 basis points 42-46 basis points Benchmark Caps and Floors: Quotations represent the premium range for buying and selling caps and floors against six month LIBOR of various maturities and strike prices. On 2/14/92, six-month LIBOR was about 4.31%. Exercise Price Type Cap Cap Floor Floor Maturity 5 years 5 years 5 years 5 years Premium bir basis points) 177- 213 106-142 801- 847 1,108-1,154 Over-the-Counter Swaption: Counterparty has the right at the end of exercise period, to force seller (GM) to pay six-month LIBOR and receive fixed rate for the length of swap. Fixed Rate Exercise Period 2 years (2 by 5) 3 years (3 by 5) Maturity of Swap 3 years 2 years Premium (in basis points) 89-108 94-111 9% 9% Over-the-Counter Options on Treasury Notes: Represent premia for call options on five-year Treasury note. The holder has the right to purchase $100 face value of Treasury notes at the end of 60 days at the strike price indicated. At the time these quotations were made, the five-year Treasury note was selling for 98.095 to yield 6.66%. Strike Frice 98.095 99.045 Premia .625 .328 Liability Management at General Motors Stephane Bello, an analyst in the Capital Markets group at General Motors (GM), oversaw liability portfolio analysis activities for America's largest domestic automaker. In February 1992, GM was planning to raise $400 million through a public offering of a noncallable five-year note, with a fixed interest rate of 7 5/8%. Guided by the firm's stated policy on liability portfolio management, the current structure of its liabilities, and his best reading of likely trends in the bond markets, Mr. Bello had to recommend to senior GM Treasurer's Office managers whether to modify GM's interest rate exposure on the issue and, if so, which transaction to select. Mr. Bello had been in the Capital Markets group at GM for one year, and during that time was responsible for analyzing the management of GM's interest-rate exposure and making recommendations about how GM could lower its borrowing costs through prudent use of interest- rate derivative products. Before taking this position, Mr. Bello had worked for two years in GM's European Regional Treasury Center, engaged in foreign exchange and corporate financing transactions. Before joining GM, he had worked in a commercial bank for over a year. Mr. Bello could advise that the firm merely issue fixed-rate debt and not engage in any related transactions. He could also suggest that GM engage in a wide range of derivative activities, which included transacting in interest-rate swaps, caps, Treasury options, or swap options (swaptions). He had solicited competitive bids for each of these instruments from several bankers. His recommendation would hinge on his judgment of the future level of interest rates and volatility, the future shape of the yield curve, and the interest-risk exposure each instrument would create in light of the overall interest-rate management program at GM. Background on General Motors and the Auto Industry In 1991, General Motors was the world's largest automaker and the nation's largest industrial company. It was broadly organized into four major operating segments: Automotive; General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC), which provided a variety of financial services; GM Hughes Flectronics, acquired in 1985, which competed in the aerospace, defense electronics, space, and telecommunications industries; and Electronic Data Services (EDS), acquired in 1984, which provided data-processing services to large corporations and institutions. GM's Automotive segment designed, manufactured, assembled, and sold automobiles, trucks, parts, and accessories. Its automotive nameplates included Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick, Cadillac, GMC Truck, and Satun in the United States, as well as Holdens, OPEL, and Vauxhall in overseas countries. While GM's nonauto businesses produced profits in 1991, its auto business sitfiered a second consecutive year of large operating losses. In 1990 the automotive segment reported an operating loss of $3.4 billion, of which $3.3 billion was a special provision for scheduled plant closings and other restructurings. In 1991 the automotive segment reported an even greater loss, $6.2 billion, of which $2.8 billion was a special provision for scheduled plant closings. In 1991 GM cut tis annual common stock dividend from $3.00 to $1.60, roughly the level it had been in 1983. In December 1991, GM's chairman and CEO, Robert C. Stempel, announced the newest cutbacks, which were scheduled to close 21 factories, cut 74,000 jobs, and slash capital spending over four years. While analysts generally supported the firm's restructuring efforts, which would ultimately cut costs by $5 billion annually, North American auto operations were not expected to become profitable for at least a few years. Exhibit 2 gives selected financial information on General Motors at a consolidated level, and Exhibit 3 gives the performance of the firm's automotive segment over the past decade. Exhibit 3 also provides information on interest rates and exchange rates during the same period of time. Financial Policies at GM At least two aspects of GM's financial strategy were reviewed in great detail in 1991. In the first of these efforts, Ray Young (who oversaw corporate finance activities in the Treasurer's Office) and his staff carefully analyzed the corporation's current capital structure policy. (See Exhibit 1 for an organization chart of the Treasurer's Office at General Motors at the time of the case.) Ultimately their conclusions regarding the GM balance sheet were reviewed by GM's Treasurer, CFO, and other senior executives. Financial targets examined, which were not announced publicly, included book value debt-to-total capital ratios, interest coverage ratios, and cash flow coverage ratios. The target ranges were set mindful of the rating agencies' guidelines, competitor's debt policies, and Young's estimates of the firm's cost of funds and its likely access to capital under various scenarios. Of utmost concern was the shared belief that declines in the company's debt ratings could make raising funds very difficult and thus lead to unintended shrinkage in the firm's auto activities. The capital structure recommendation provided policy direction and guidance to the Capital Markets group charged with executing specific transactions. Nevertheless, the Capital Markets group had wide latitudefor example, issuing "debt" implied a set of decisions about which market the instrument would tap (domnestic U.S. Euromarkets, or other), the maturity of the instrument, its interest rate (fixed or floating), and other specific terms like callable features, sinking funds, etc.? In addition, the capital markets in the 1980s and early 1990s had developed an almost unbounded number of derivative instruments that could dramatically alter the fundamental economics of an offering. For example, a firm could issue a fixed-rate note, and then engage in a swap transaction with a financal institution to pay a floating rate tied to LIBOR and receive a fixed rate. The issuer then effectively transformed the fixed-rate issue into a LIBOR-linked floating-rate note. GM did not engage in derivative transactions to modify the interest-rate exposure of its debt offerings until 1989, when the manager of the Capital Markets group suggested that the firm experiment with swaps and other interest-rate derivatives to lower GM's borrowing costs. This effort proceeded after receiving ultimate approval from the Finance Committee of the Board of Directors. However, throughout 1989 and 1990, GM's borrowing needs were modest, and thus it engaged in very few interest-rate derivative transactions. The early transactions were structured as relatively low-risk experiments designed to reduce GM's cost of debt. Because the group lacked internal capabilities to price interest-rate derivatives, it was decided that GM would engage in transactions only when they could obtain independent prices from competing financial institutions. Requiring multiple vendors to submit bids may have ruled out some of the most esoteric transactions in the market, but it also gave GM some assurance that it would not be at the mercy of one bank if it wanted to unwind its positions before maturity. Beginning with its 1990 annual report, GM notified the public of its use of interest rate derivatives to manage its exposure as part of its SFAS 105 disclosure: The Corporation primarily utilizes interest-rate-forward contracts or options to manage its interest-rate exposure. Interest-rate-forward contracts are contractual agreements between the Corporation and another party to exchange fixed and floating interest-rate payments periodically over the life of the agreement without the exchange of underlying principal amounts. Interest-rate options generally permit but do not require the purchaser of the option to exchange interest-rate payments in the future. At December 31, 1990, the total notional amount of such agreements with off- balance sheet risk was approximately $7,787 million.' By the end of 1991, this notional principal equaied $7,354 million. The amounts disclosed in GM's annual reports included interest-rate derivatives transactions executed by GMAC. However, the New York Treasurer's Office was not directly involved with GMAC's liability management program, which was handled out of GMAC's Treasury operations in Detroit. The required disclosure contained in the GM financial statements did not reveal the number, complexity, or economic exposure brought about by the firm's recent interest-rate management activities. For example, in its first two years of managing interest-rate risk actively, GM had entered into seven different transactions, including a single interest swap and a handful of more complicated swap options or swaptions. In 1991, GM's liability management program became more formalized and increased in scope, for in that year the firm entered into 40 interest-rate derivative transactions. This increase in scale was facilitated by the hiring of a full-time analyst charged with analyzing and recommending potential structures to manage CM's growing liability portfolio. The heightened activity also led to a formal review of GM's liability management policies. This review sought to evaluate the firm's first two years of experience in managing the structure of its debl, as well as lo lay oul guidelines for 'uiure liability management activities. This policy review set broad boundaries within which interest rate management of Central Office debt obligations would take place. The 1991 Review of GM's Liability Management Program The 1991 review established a rationale and a set of policies for managing the debt of GM's auto operations, just as the review of capital structure provided a long-term view of the firm's mix of debt and equity. The report covered the goal of the program, the economic rationale for a "home base" mix of fixed/floating obligations, the role of changing market conditions on the active management of the portfolio, corporate governance concerns, and criteria for counterparty credit exposure. The following excerpts summarize key findings: Goal: "To actively manage the Central Office liabilities to take advantage of the cyclical nature and volatility of domestic interest rates and shiits in the shape of the yield curve to reduce GM's overall cost of funds. Home base: "Asset/Liability management can be broadly defined as matching the nature of a company's liabilities to its assets to limit the impact of interest-rate movements on the company's net cash flows and hence corporate value. In general, this is accomplished by adjusting a firm's financial liability portfolio such that any impact on operating cash flow caused by movements in interest rates is largely offset by changes in the value of the firm's liability portfolio "(In) industrial companies ... the impact of changes in interest rates on operating cash flows is hard to quantify. ... In addition, the right-hand side of an industrial company's balance sheet tends to comprise a higher percentage of equity and noninterest-bearing liabilities (i.e., accounts payable, reserves for warranties, incentives, and deferred taxes) than a financial institution's. This means that, even if the correlation between changes in interest rates and changes in operating cash flows could be perfectly established, the value of financial liabilities would probabiy have to be hedged to an extreme to obtain the desired results. "GM's North American automotive revenues and hence operating cash flows are strongly influenced by rovements in interest-rates ... a 1% decrease in auto loan rates results in a 0.2% increase in the dollar volume of cars sold.? ... GM's automotive operations behave more like fixed-rate assets than floating-rate assets... Therefore, GM's Central Office liability portfolio should be predominantly fixed-rate in nature to provide the greatest insulation to GM's cash flows from a rising interest-rate/slow automotive market. "Although a fixed / floating rate mix of 100/0 would completely insulate GM's debt service cash flows from rising interest rates... (1) it would ignore the cost benefits to be derived by holding some short-term cent in light of the generally upward sloping shape of we yer curve; and (2) it would force GM to issue fixed-rate debt even when interest rates are at high historical levels. [The report then summarized GM's interest costs for its Central Office debt portfolio, under various fixed/floating proportions in two scenarios: the fixed-floating spread holds at the historical average level, and the fixed-floating spread widens to early 1980s levels.] "Given the outlook for weak operating profits in upcoming years, it does not appear appropriate to assume a significant amount of risk with the Central Office debt portfolio. However, neither does it appear appropriate to ignore the savings over time of floating-rate debt. Although not a scientifically determined mix, a fixed/floating split in the neighborhood of 75%-80% fixed/25%-20% floating appears to be an appropriate balance of these considerations...[or a home base." Active management around home base: "Essentially, a liability management program is an attempt to take advantage of the cyclical nature of interest rates, the volatility of interest rates, and the changing shape of the yield curve. By adjusting the composition of GM's liability portfolio in step with changes in rates over time, GM should be able to accomplish a meaningful reduction in total debt service costs. "In general, a fixed/floating mix of less than 75/25 reflects GM's belief that short-term (floating) rates are more attractive than long-terin fixed-interest rates, while a fixed/floating mix of greater than 75/25 reflects GM's belief that long-term fixed rates are more attractive than short-term (floating) rates. In addition, eption strategies can add flexibility and significantly reduce GM's overall cost of funds. In general, GM would sell options when interest-rate volatility is high or wher: an abnormally shaped yield curve provides opportunities." Corporate control concerns: "All swap and swap-option transactions (must) be reviewed with and executed under the approval of the Treasurer. ... Transaction reviews would be conducted with consideration given to historical interest rates, the current interest-rate environment as well as the forecast of our position on the interest-rate cycle and the fit of the transaction within the strategic shift in the Central Office fixed/floating mix. The fixed/floating mix will be maintained within the range of 100/0 and 50/50 which should provide GM with sufficient flexibility to actively manage GM's portfolio while maintaining a minimum conservative level of 50% fixed-rate debt." Countenarty exposure: The final section of the report described GM's policies regarding swap and option counterparty creditworthiness. Specifically, it detailed the minimum credit ratings required for various types of financial transactions, and the maximum allowable exposure the firm could have to any one financial institution. The February 1992 Decision ir determining what recommendation to make about the interest-rate exposure of the proposed $100-million fixed-rate offering, Stephane Bello had to sort through the mandates of the 1991 policy review, GM's current interest-rate exposure, his best guess of future interest rates, and the specific alternatives from which he could choose. The first two of these were quite clear the memo set broad restrictions on the liability management activities, especially given the current porifolio of debt obligations and interest-rate derivatives, summarized in Exhibit 5. His recommendation wouid also be affected by his "rate view" and the instruments at his disposal Development of the February 1992 "Rate View" Predictions of the level of interest rates, the shape of the yield curve, and volatility of interest rates would figure prominently in Mr. Bello's recommendation. The Treasurer, charged with managing the liability management program, relied on his finance staff and the firm's bankers for input. Mr. Bello and other members of the Capital Markets group at GM were in contact with over 20 economists who offered their insights. Exhibit 6 summarizes a few banks' published forecasts as of February 1992. In addition, internal GM data on forecasts of auto sales and other items provided some information about the direction of the economy. Due to the size of GM in the economy and to the magnitude of its banking needs, the staff at GM felt that it had access to more, better, and more timely information than the market as a whole with which it could make more intelligent interest-rate calls. Nevertheless, they acknowledged that arriving at a rate view was an art, not a science, and that their predictions would sometimes be in error. In February 1992 the rate view shared by the Capital Markets section of the Treasurer's Office was that "rates were likely to decline from their current levels as the market digests the heavy supply of bonds sold by the U.S. Treasury" due to the recent quarterly refunding of Treasury debt, and that the bond market "is likely to rally (i.e., rates will decine) over the next two months as participants focus on fundamentals that point to a continued weak economy during the first half of the year." In addition, they felt that there is currently a high level of uncertainty in the market with regard to the direction of interest rates over the next few months." Finally, they agreed that the yield curve would flatten as the spread between long and short rates converged. Exhibit 7 shows interest rates and forward rates in February 1992. Stephane Bello's Alternatives While GM's Treasurer was altimately responsible for the liability management program, the degree to which the execution of the program was delegated depended on the scope, novelty, and change in rate view implied by the transaction. Transactions of large size or novel structure, or those whose positions refiected fundamental shifts in rate view, were carefully scrutinized by senior Treasury managers. On transactions like the one Mr. Bello was currently contemplating, his recommendation would carry much weight The terns of the $400-million five-year 7 5/8% coupon note that would be issued were straightforward. GM would make ten semiannual interest payments of $15.25 million and a final principal repayment of S400 million at maturity. Before maturity, GM had no call provisions, nor did the nose establish a sinking fund. GM had no right to extend the maturity of the note beyond five years. The notes would be sold to the public for 99.976 per $100 value for gross proceeds of $399,904,000. GM would pay its underwriters commissions of S1.8 million and expenses of $175,000 Mr. Bello had an almost unlimited set of alternatives for adjusting GM's interest-rate exposure on this offering. Five generic alternatives were: (1) enter into an interest-rate swap; (2) sell caps; (3) buy or sell an option on an interest-rate swap (known as a swap option or swaption); (4) buy or sell options on a five-year Treasury instrument, or (5) do nothing. The following discussion describes the various choices open to GM, and Exhibit 8 gives representative quotes on these instruments frem counterparties meeting GM's credit standards. GM's policy was that any interest rate derivative position it entered into must be acceptable to the firm if GM was forced to hold it to maturity, or if a counterparty exercised any options against GM. However, GM's expectation, based on its rate view at the time the derivatives were put in place, was that it would be able to unwind its position within six months at a profit. As a result, GM entered into transactions only with multiple bidders, where the firm was likely to be able to unwind its position in the near term with a minimum of transaction costs. Swaps To transform the five-year fixed-rate obligation into a floating-rate obligation, GM could enter into an interest-rate swap. In an interest-rate swap, two parties in effect agree to exchange their interest rate obligations. For example, GM could agree to pay, over the next five years, a floating rate (based on LIBOR) on $400 million and to receive a fixed interest rate. The counterparty to this transaction would agree to pay a fixed interest rate on the $400 million and receive a floating rate. The $400 million principal amount of the swap (called the notional amount) never changes hands. In practice, the two offsetting interest payments are netted against one another so that only the difference between the payments is exchanged. 10 Typically, no funds change hands at the initiation of a swap. Since 1986 the Treasurer's Office had entered into eight interest-rate swaps, seven of which were done in 1991.11 In the early 1980s when first introduced, interest-rate swaps were executed between different borrowers who would come to market simultaneously and also enter into the swap agreement, often with a financial intermediary serving as broker and as guarantor of the differential interest payments. However, financial intermediaries soon began to become dealers in the swap market, taking positions and managing the interest rate and credit risk of their portfolio of swaps on their "swaps book." GM's policies regarding its swap counterparties were thus designed to reduce its exposure were one of its financial intermediary swap counterparties to fail. A wide variety of interest-rate swap structures could be used: counterparties could agree to virtually any structure of the notional principal (e.g., flat, amortizing over time, stepping up over time) and any set of different interest rates (e.g., fixed for LIBOR, fixed for Treasury bills, LIBOR for Treasury bills). In addition, swaps could be structured for current execution or for future execution (e.g., in a forward, deferred, or delayed-start swap, the counterparties agree to enter into a particular swap whose payments will not begin until some point in the future.) Typically, swap participants were free to buy out their counterparties by paying the market price reflecting the net gain to the other party of canceling the contract. Mr. Bello had received bids from various banks to which GM could sell these swaptions, and he was considering two proposals. Both gave the counterparty the right at the end of a fixed period of time, to force GM to pay LIBOR and receive a fixed rate for the length of the swap. In the "3 by 5" European swaption proposal, at the end of the third year the counterparty had the right to force GM to receive 9% and pay LIBOR for the following two years. In the "2 by 5" proposal, the counterparty had to decide at the end of two years whether to force GM into a three-year swap of 9% for LIBOR. Exhibit 8 gives the premia for these transactions. GM entered into 25 swaption transactions in 1991, with notional principal involved of $2.6 billion. There were only a handful of qu

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts