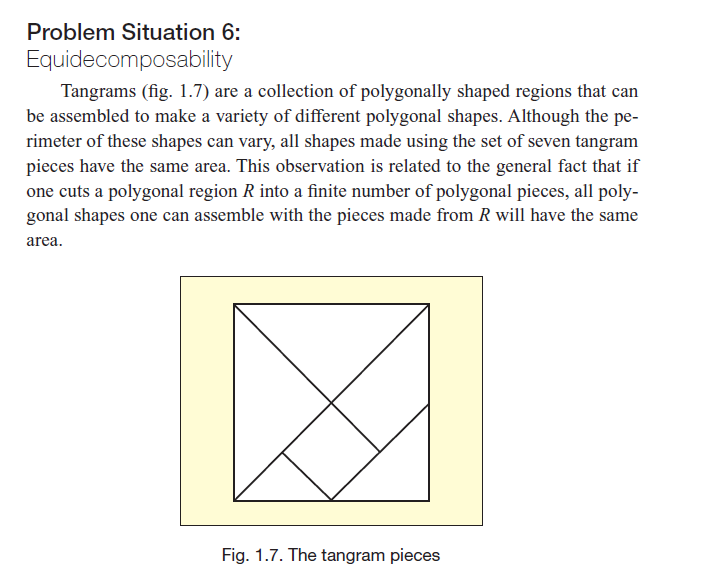

Question: Problem Situation 6: Equidecomposability Tangrams (fig. 1.7) are a collection of polygonally shaped regions that can be assembled to make a variety of different polygonal

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock