Question: Purpose The purpose of this activity is to develop your ability to reduce the information from a case into a format that will provide you

Purpose

The purpose of this activity is to develop your ability to reduce the information from a case into a format that will provide you with a helpful reference in class and for review. You are reviewing, identifying, and reporting the IRAC elements of the case.

In your summary, aka brief, you will identify the problem the court faced (the issue); the relevant law the court used to solve it (the rule); how the court applied the rule to the facts (the application or analysis); and the outcome (the conclusion).

Using the IRAC framework to summarize a case will help you prepare for discussion about the case as well as improve your ability to compare and contrast it to other cases involving a similar issue.

Instructions

Read the assigned case and prepare a written summary of the case using the IRAC framework.

Include a header with your name, date, course title, and assignment name on the first page, no title page needed.

Include reference page that lists the sources of information that used as a basis of your work. You are encouraged to look online for examples and are required to cite sources used to develop your IRAC summary

Include five section headings in your summary: Case Name, Issue, Rule, Analysis, & Conclusion. While Facts and Procedural History are very important in your preparation, do not include these as sections within your summary. Incorporate fact and history as needed in Analysis section.

Resources

Here are resources that will assist you IRAC case analysis:

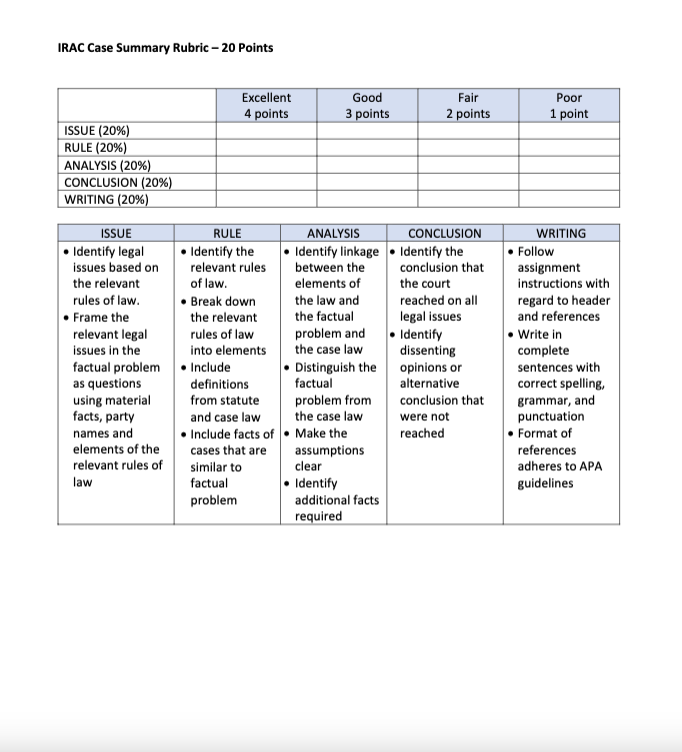

IRAC Case Summary 20 Point Rubric.pdfDownload IRAC Case Summary 20 Point Rubric.pdf

Case Summary Example_Palsgraf.pdfDownload Case Summary Example_Palsgraf.pdf

Helpful Hints to Writing a Better IRACLinks to an external site. (Link to article)

Case

Using the IRAC framework, provide a summary of this case: BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB CO. v. SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO COUNTY, ET AL

SCOTUS Bristol-Meyers Squib V Sup. Cout of CA.pdfDownload SCOTUS Bristol-Meyers Squib V Sup. Cout of CA.pdf

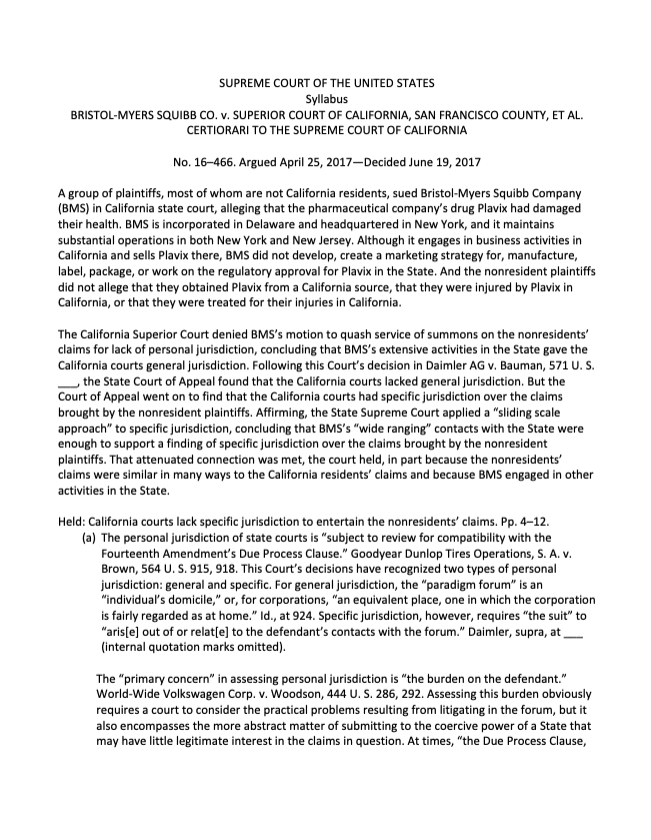

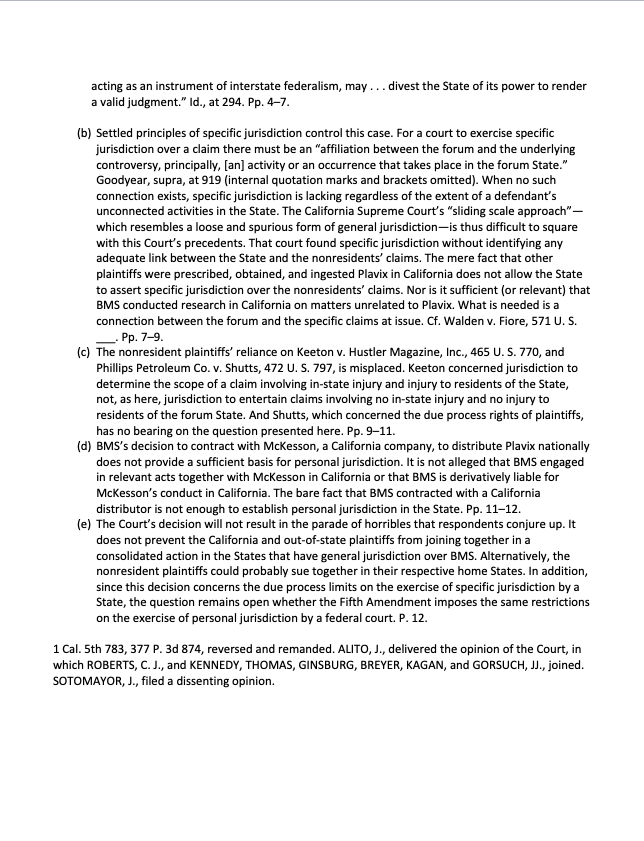

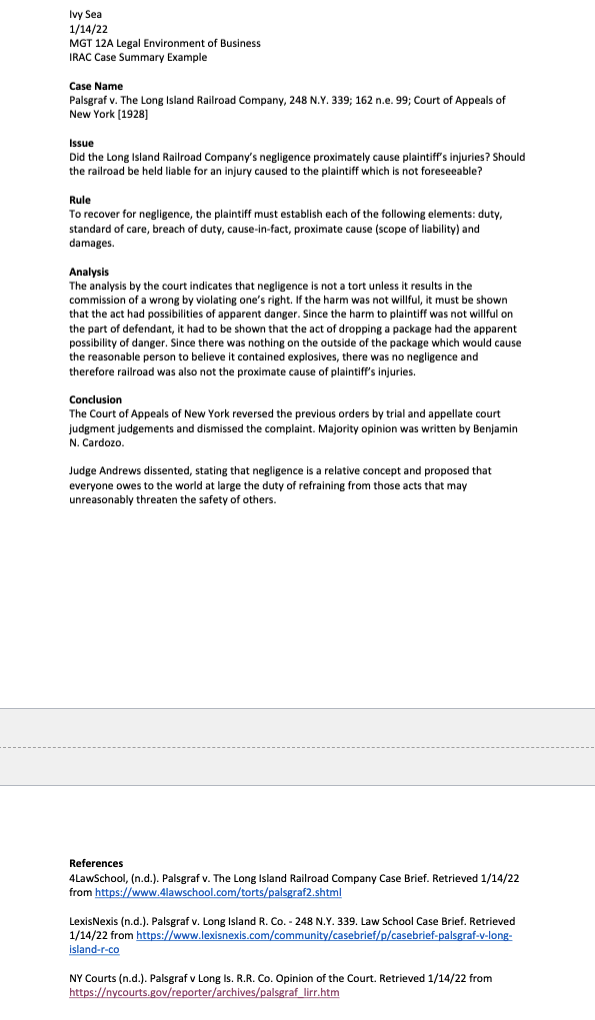

The purpose of this activity is to develop your ability to reduce the information from a case into a format that will provide you with a helpful reference in class and for review. You are reviewing, identifying, and reporting the IRAC elements of the case. In your summary, aka brief, you will identify the problem the court faced (the issue); the relevant law the court used to solve it (the rule); how the court applied the rule to the facts (the application or "analysis"); and the outcome (the conclusion). Using the IRAC framework to summarize a case will help you prepare for discussion about the case as well as improve your ability to compare and contrast it to other cases involving a similar issue. Instructions Read the assigned case and prepare a written summary of the case using the IRAC framework. Include a header with your name, date, course title, and assignment name on the first page, no title page needed. Include reference page that lists the sources of information that used as a basis of your work. You are encouraged to look online for examples and are required to cite sources used to develop your IRAC summary Include five section headings in your summary: Case Name, Issue, Rule, Analysis, \& Conclusion. While Facts and Procedural History are very important in your preparation, do not include these as sections within your summary. Incorporate fact and history as needed in Analysis section. Resources Here are resources that will assist you IRAC case analysis: IRAC Case Summary 20 Point Rubric.pdf Case Summary Example Palsgraf.pdf Helpful Hints to Writing a Better IRAC (Link to article) Case Using the IRAC framework, provide a summary of this case: BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB CO. v. SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO COUNTY, ET AL SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus BRISTOL-MYERS SQUIBB CO. v. SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO COUNTY, ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF CALIFORNIA No. 16-466. Argued April 25, 2017-Decided June 19, 2017 A group of plaintiffs, most of whom are not California residents, sued Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (BMS) in California state court, alleging that the pharmaceutical company's drug Plavix had damaged their health. BMS is incorporated in Delaware and headquartered in New York, and it maintains substantial operations in both New York and New Jersey. Although it engages in business activities in California and sells Plavix there, BMS did not develop, create a marketing strategy for, manufacture, label, package, or work on the regulatory approval for Plavix in the State. And the nonresident plaintiffs did not allege that they obtained Plavix from a California source, that they were injured by Plavix in California, or that they were treated for their injuries in California. The California Superior Court denied BMS's motion to quash service of summons on the nonresidents' claims for lack of personal jurisdiction, concluding that BMS's extensive activities in the State gave the California courts general jurisdiction. Following this Court's decision in Daimler AG v. Bauman, 571 U. S. _ the State Court of Appeal found that the California courts lacked general jurisdiction. But the Court of Appeal went on to find that the California courts had specific jurisdiction over the claims brought by the nonresident plaintiffs. Affirming, the State Supreme Court applied a "sliding scale approach" to specific jurisdiction, concluding that BMS's "wide ranging" contacts with the State were enough to support a finding of specific jurisdiction over the claims brought by the nonresident plaintiffs. That attenuated connection was met, the court held, in part because the nonresidents' claims were similar in many ways to the California residents' claims and because BMS engaged in other activities in the State. Held: California courts lack specific jurisdiction to entertain the nonresidents' claims. Pp. 4-12. (a) The personal jurisdiction of state courts is "subject to review for compatibility with the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause." Goodyear Dunlop Tires Operations, S. A. v. Brown, 564 U. S. 915, 918. This Court's decisions have recognized two types of personal jurisdiction: general and specific. For general jurisdiction, the "paradigm forum" is an "individual's domicile," or, for corporations, "an equivalent place, one in which the corporation is fairly regarded as at home." Id., at 924. Specific jurisdiction, however, requires "the suit" to "aris[e] out of relat[e] to the defendant's contacts with the forum." Daimler, supra, at (internal quotation marks omitted). The "primary concern" in assessing personal jurisdiction is "the burden on the defendant." World-Wide Volkswagen Corp. v. Woodson, 444 U. S. 286, 292. Assessing this burden obviously requires a court to consider the practical problems resulting from litigating in the forum, but it also encompasses the more abstract matter of submitting to the coercive power of a State that may have little legitimate interest in the claims in question. At times, "the Due Process Clause, acting as an instrument of interstate federalism, may ... divest the State of its power to render a valid judgment." Id., at 294. Pp. 4-7. (b) Settled principles of specific jurisdiction control this case. For a court to exercise specific jurisdiction over a claim there must be an "affiliation between the forum and the underlying controversy, principally, [an] activity or an occurrence that takes place in the forum State." Goodyear, supra, at 919 (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted). When no such connection exists, specific jurisdiction is lacking regardless of the extent of a defendant's unconnected activities in the State. The California Supreme Court's "sliding scale approach"which resembles a loose and spurious form of general jurisdiction-is thus difficult to square with this Court's precedents. That court found specific jurisdiction without identifying any adequate link between the State and the nonresidents' claims. The mere fact that other plaintiffs were prescribed, obtained, and ingested Plavix in California does not allow the State to assert specific jurisdiction over the nonresidents' claims. Nor is it sufficient (or relevant) that BMS conducted research in California on matters unrelated to Plavix. What is needed is a connection between the forum and the specific claims at issue. Cf. Walden v. Fiore, 571 U. S. . Pp. 7-9. (c) The nonresident plaintiffs' reliance on Keeton v. Hustler Magazine, Inc., 465 U. S. 770, and Phillips Petroleum Co. v. Shutts, 472 U. S. 797, is misplaced. Keeton concerned jurisdiction to determine the scope of a claim involving in-state injury and injury to residents of the State, not, as here, jurisdiction to entertain claims involving no in-state injury and no injury to residents of the forum State. And Shutts, which concerned the due process rights of plaintiffs, has no bearing on the question presented here. Pp. 9-11. (d) BMS's decision to contract with McKesson, a California company, to distribute Plavix nationally does not provide a sufficient basis for personal jurisdiction. It is not alleged that BMS engaged in relevant acts together with McKesson in California or that BMS is derivatively liable for McKesson's conduct in California. The bare fact that BMS contracted with a California distributor is not enough to establish personal jurisdiction in the State. Pp. 11-12. (e) The Court's decision will not result in the parade of horribles that respondents conjure up. It does not prevent the California and out-of-state plaintiffs from joining together in a consolidated action in the States that have general jurisdiction over BMS. Alternatively, the nonresident plaintiffs could probably sue together in their respective home States. In addition, since this decision concerns the due process limits on the exercise of specific jurisdiction by a State, the question remains open whether the Fifth Amendment imposes the same restrictions on the exercise of personal jurisdiction by a federal court. P. 12. 1 Cal. 5th 783, 377 P. 3d 874, reversed and remanded. ALITO, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which ROBERTS, C. J., and KENNEDY, THOMAS, GINSBURG, BREYER, KAGAN, and GORSUCH, JJ., joined. SOTOMAYOR, J., filed a dissenting opinion. IRAC Case Summary Rubric - 20 Points Ivy Sea 1/14/22 MGT 12A Legal Environment of Business IRAC Case Summary Example Case Name Palsgraf v. The Long Island Railroad Company, 248 N.Y. 339; 162 n.e. 99; Court of Appeals of New York [1928] Issue Did the Long Island Railroad Company's negligence proximately cause plaintiff's injuries? Should the railroad be held liable for an injury caused to the plaintiff which is not foreseeable? Rule To recover for negligence, the plaintiff must establish each of the following elements: duty, standard of care, breach of duty, cause-in-fact, proximate cause (scope of liability) and damages. Analysis The analysis by the court indicates that negligence is not a tort unless it results in the commission of a wrong by violating one's right. If the harm was not willful, it must be shown that the act had possibilities of apparent danger. Since the harm to plaintiff was not willful on the part of defendant, it had to be shown that the act of dropping a package had the apparent possibility of danger. Since there was nothing on the outside of the package which would cause the reasonable person to believe it contained explosives, there was no negligence and therefore railroad was also not the proximate cause of plaintiff's injuries. Conclusion The Court of Appeals of New York reversed the previous orders by trial and appellate court judgment judgements and dismissed the complaint. Majority opinion was written by Benjamin N. Cardozo. Judge Andrews dissented, stating that negligence is a relative concept and proposed that everyone owes to the world at large the duty of refraining from those acts that may unreasonably threaten the safety of others. References 4LawSchool, (n.d.). Palsgraf v. The Long Island Railroad Company Case Brief. Retrieved 1/14/22 from https://www.4lawschool.com/torts/palsgraf2.shtml LexisNexis (n.d.). Palsgraf v. Long Island R. Co. - 248 N.Y. 339. Law School Case Brief. Retrieved 1/14/22 from https://www.lexisnexis.com/community/casebrief/p/casebrief-palsgraf-v-longisland-r-co NY Courts (n.d.). Palsgraf v Long Is. R.R. Co. Opinion of the Court. Retrieved 1/14/22 from https:/ycourts.gov/reporter/archives/palsgraf lirr.htm

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts